George Johnson

George Johnson writes about science for the New York Times from Santa Fe, New Mexico, and is winner of the 1999 AAAS Science Journalism Award. His books include Fire in the Mind: Science, Faith, and the Search for Order and Strange Beauty: Murray Gell-Mann and the Revolution in 20th-Century Physics. His seventh book, Miss Leavitt's Stars, will be published in June by Norton. A graduate of the University of New Mexico and American University, his first reporting job was covering the police beat for the Albuquerque Journal. He is now co-director of the Santa Fe Science-Writing Workshop.

| Column |

On Top of Microwave MountainI tried to saute my brain at the base of a cell phone tower. It didn't work.  Not many people drive all the way to the top of Sandia Crest, 10,678 feet, to hang out by the Steel Forest—the thick stand of blinking broadcast and microwave antennas that serves as a communications hub for New Mexico and the Southwest. But I went there on a dare. For the past few months, I've been trying to understand the thinking of some anti-wireless activists who have turned my town, Santa Fe, N.M., into a hotbed for people who believe that microwaves from cell phones and Wi-Fi are causing everything from insomnia, nausea, and absent-mindedness to brain cancer. "Spend an hour or two in front of the antennas," I was advised by Bill Bruno, a Los Alamos National Laboratory physicist and self-diagnosed "electrosensitive" who sometimes attends public hearings wearing a chain-mail-like head dress to protect his brain. "See if aspirin cures the headache you'll probably get, and see if you can sleep that night without medication." So while carloads of visitors took in the high mountain air and breathtaking views of the Rio Grande Valley, I wandered around with a handheld microwave meter to make sure that I spent no less than two hours basking in high-frequency electromagnetism at an intensity of up to 1 milliwatt per square centimeter. (That is the threshold set by the FCC for safe exposure over a 30-minute interval.) The device also measured the magnetic fields buffeting the mountain, which spiked at 100 milligauss, about one-five-hundredth as strong as a refrigerator magnet. My head felt fine as I drove back to Santa Fe, and I slept soundly that night, reinforcing my doubts that the growing presence of wireless communication devices can be blamed for anything worse than sporadic outbreaks of hysteria, which has been defined in the psychiatric literature as "behavior that produces the appearance of disease." |

| Review |

Review: 'The Hidden Brain' by Shankar Vedantam Sen. Harry Reid has faced sharp criticism for speculating during the 2008 campaign that Barack Obama may have had an advantage as a black presidential candidate because of his light skin. But a practical test carried out by the Obama campaign -- and now revealed in Shankar Vedantam's book, "The Hidden Brain" -- suggests that Reid may have been on target. Near the end of the race, Democratic strategists considered combating racial bias by running feel-good television advertisements. The campaign made two versions of the same ad. One featured images of a white dad and two black dads in family settings reading "The Little Engine That Could" to their daughters. The other depicted similar scenes with a white dad and a light-skinned black dad. The first version got high ratings from focus groups, but it did not budge viewers' attitudes toward Obama. The second version elicited less overt enthusiasm, but it increased viewers' willingness to support the candidate. The spots never aired in part, Vedantam writes, because of budget problems. Vedantam, a science reporter for The Washington Post, saw these ads in the course of his reporting on the science of the unconscious mind. The contrast between viewers' expressed sentiments and their inclinations as voters is, he argues, evidence of the unconscious in action -- in this case, through bias against dark skin. "We are going back to the future to Freud" with this application of science to politics, explains Drew Westen, a psychologist who advised the Obama campaign. We may be heading back farther yet. Before Freud, the unconscious was understood as a social monitor. Illustrating this limited concept, Freud's collaborator, Joseph Breuer, once wrote that he would suffer "feelings of lively unrest" if he had neglected to visit a patient on his rounds. Freud proposed a more complex, creative unconscious, one that accessed forgotten facts and feelings and, using poetic logic, concocted meaningful dreams, medical symptoms and slips of the tongue. A common example of a misstep provoked by the psychoanalytic unconscious has a young man calling a woman a "breast of fresh air" and then correcting himself: "I mean, a breath of flesh air." This clever unconscious has fallen on hard times. While contemporary research finds that mental processes occurring outside awareness shape our decisions, the unconscious revealed in those studies is stodgy. It uses simple mechanisms to warn us of risks and opportunities -- and often it is simply wrong. |

| Article |

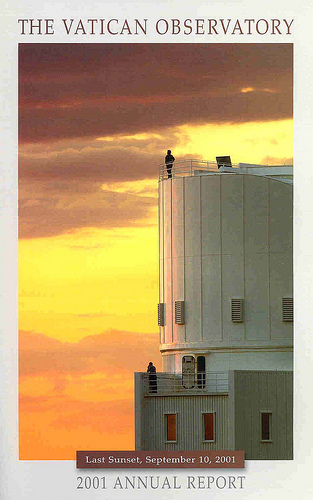

Vatican’s Celestial Eye, Seeking Not Angels but Data MOUNT GRAHAM, Ariz. — Fauré’s “Requiem” is playing in the background, followed by the Kronos Quartet. Every so often the music is interrupted by an electromechanical arpeggio — like a jazz riff on a clarinet — as the motors guiding the telescope spin up and down. A night of galaxy gazing is about to begin at the Vatican’s observatory on Mount Graham. “Got it. O.K., it’s happy,” says Christopher J. Corbally, the Jesuit priest who is vice director of the Vatican Observatory Research Group, as he sits in the control room making adjustments. The idea is not to watch for omens or angels but to do workmanlike astronomy that fights the perception that science and Catholicism necessarily conflict. Last year, in an opening address at a conference in Rome, called “Science 400 Years After Galileo Galilei,” Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, the secretary of state of the Vatican, praised the church’s old antagonist as “a man of faith who saw nature as a book written by God.” In May, as part of the International Year of Astronomy, a Jesuit cultural center in Florence conducted “a historical, philosophical and theological re-examination” of the Galileo affair. But in the effort to rehabilitate the church’s image, nothing speaks louder than a paper by a Vatican astronomer in, say, The Astrophysical Journal or The Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. On a clear spring night in Arizona, the focus is not on theology but on the long list of mundane tasks that bring a telescope to life. As it tracks the sky, the massive instrument glides on a ring of pressurized oil. Pumps must be activated, gauges checked, computers rebooted. The telescope’s electronic sensor, similar to the one in a digital camera, must be cooled with liquid nitrogen to keep the megapixels from fuzzing with quantum noise. As Dr. Corbally rushes from station to station flicking switches and turning dials, he seems less like a priest or even an astronomer than a maintenance engineer. Finally when everything is ready, starlight scooped up by the six-foot mirror is chopped into electronic bits, which are reconstituted as light on his video screen. “Much of observing these days is watching monitors and playing with computers,” Dr. Corbally says. “People say, ‘Oh, that must be so beautiful being out there looking at the sky.’ I tell them it’s great if you like watching TV.” Dressed in blue jeans and a work shirt, he is not a man who wears his religion on his sleeve. No grace is offered before a quick casserole dinner in the observatory kitchen. In fact, the only sign that the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope is fundamentally different from the others on Mount Graham, the home of an international astronomical complex operated by the University of Arizona, is a dedication plaque outside the door. |

| Article |

Everything Is IlluminatiWhy can't the Catholic Church shake free of a 200-year-old conspiracy theory?  About eight years ago here in Santa Fe, N.M., everybody was talking about the bikini Virgin. That's virgin with a capital V—and the reference was to a piece of art on exhibition at a local museum, in which Our Lady of Guadalupe, the most beloved figure in New Mexico Catholicism, was depicted in a skimpy floral bathing suit with as many colors as a birthday piñata. Angry Catholics demanded that the image be removed from the show, but it stayed on display until the exhibition closed, and the young artist who created it received the kind of career boost that only comes with being denounced from the pulpit. The controversy has long since faded but I thought about it again last night as I waited in line for an advance screening of Angels & Demons, the new thriller (based on a Dan Brown novel) in which the Vatican comes across as an age-old enemy of reason and scientific truth. The movie, which has already been denounced in the United States by William Donohue of the conservative Catholic League, stars (along with Tom Hanks) a legendary cabal called the Illuminati—a group of evil eggheads who have figured in various conspiracy theories for more than 200 years. This time, they are plotting (or so it seems) to vaporize the Vatican as punishment for centuries of oppression against freethinkers. I was a little disappointed when when there were no picketers at the theater passing out copies of Donohue's new tract, |

| Review |

Far Out With plumes of gas and stardust reaching up like the fingers of Adam and a purple sun winking back, the “Pillars of Creation” has the high ecclesiastical wattage of a Michelangelo. But this late-20th-century masterpiece wasn’t painted by human hands. It is a digital image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope of the Eagle nebula, a celestial swarm 7,000 light-years from Earth. While the image is embraced sometimes by Christians to evoke the Garden of Eden or the Pearly Gates, what we are seeing is something real and more inspiring: a cosmic incubator hatching new stars. Reproduced on calendars and book jackets and in coffee-table books, “Pillars of Creation” belongs among the iconic images of modern times — right up there with the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima and Ansel Adams’s “Moon and Half Dome, Yosemite National Park.” More than an artifact of technology, “Pillars of Creation” is a work of art. As John D. Barrow, a professor of mathematical sciences at Cambridge University, writes in COSMIC IMAGERY: Key Images in the History of Science (Norton, $39.95), pulling such an arresting canvas from the digital signals beamed by Hubble required aesthetic choices much like those that went into the great landscape paintings of the American West. There is no reason, for example, why the plumes had to be shown standing up. There are no directions in space. More important, the scientists processing the bit stream chose the color palette partly for dazzling effect. “If you were floating in space you would not ‘see’ what the Hubble photographs show in the sense that you would see what my passport photo shows if you met me,” Barrow writes. Following a suggestion by an art historian, Elizabeth Kessler, he juxtaposes “Pillars of Creation” with Thomas Moran’s “Cliffs of the Upper Colorado River, Wyoming Territory.” Both works “draw the eyes of the viewer to the luminous and majestic peaks,” Barrow writes. “The great pillars of gas are like a Monument Valley of the astronomical landscape.” Through dozens of short essays, each prompted by one of science’s visual creations, Barrow conducts his own personal tour of the universe. A picture of the Whirlpool Galaxy, with its double spirals, sets him to wondering whether it was the spark for van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” The Crab nebula, the remnant of an exploding star viewed by Chinese astronomers in 1054, leads into a short discussion of pulsars, distant lights that blink so rhythmically that astronomers once wondered whether they were semaphores from L.G.M.’s — “little green men.” |

| Review |

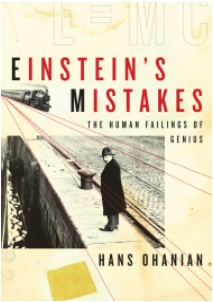

Gotcha, Physics Genius: Einstein's MistakesRetelling Albert Einstein's story by homing in on his blunders makes for good intellectual entertainment. BOOK REVIEW  When Donald Crowhurst's abandoned sailboat was found adrift in the Atlantic in 1969, his captain's log recorded the ravings of a man whose mind had snapped. On page after page, he spouted fulminations and pseudoscience, finally ripping his chronometer from its mountings and throwing it and then himself into the drink. During the voyage, an around-the-globe sailboat race, Crowhurst had been reading Einstein's book "Relativity: The Special and the General Theory." A chapter called "On the Idea of Time in Physics" seems to have pushed him over the edge. Einstein was pondering what it means to say that two lightning bolts strike the ground simultaneously. For this to be true, he suggested, someone positioned halfway between the events would have to observe the flashes occurring at the same instant. That assumes that the two signals are traveling at the same speed -- a condition, Einstein wrote, rather oddly, that "is in reality neither a supposition nor a hypothesis about the physical nature of light, but a stipulation which I can make of my own free will in order to arrive at a definition of simultaneity." "You can't do THAT!" Crowhurst, an electrical engineer, protested to his journal. "I thought, 'the swindler.' " From there he descended into madness. Hans C. Ohanian, who tells this strange tale at the beginning of "Einstein's Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius," sympathizes with poor Crowhurst. "The speed of light is either constant or not, and only measurement can decide what it is," Ohanian writes. For Einstein to make a postulation rather than propose it as a hypothesis to be tested may seem like a fine distinction. (Earlier in his book, Einstein does cite an empirical basis for his assumption: the Dutch astronomer Willem de Sitter's paper, "An Astronomical Proof for the Constancy of the Speed of Light," which was based on observations of binary stars.) But to Ohanian, the act was as outrageous as when Indiana lawmakers tried to legislate the value for pi. And so he adds it to his roster of Einstein's mistakes. |

| Article |

Vanished: A Pueblo Mystery Perched on a lonesome bluff above the dusty San Pedro River, about 30 miles east of Tucson, the ancient stone ruin archaeologists call the Davis Ranch Site doesn’t seem to fit in. Staring back from the opposite bank, the tumbled walls of Reeve Ruin are just as surprising. Some 700 years ago, as part of a vast migration, a people called the Anasazi, driven by God knows what, wandered from the north to form settlements like these, stamping the land with their own unique style. “Salado polychrome,” says a visiting archaeologist turning over a shard of broken pottery. Reddish on the outside and patterned black and white on the inside, it stands out from the plainer ware made by the Hohokam, whose territory the wanderers had come to occupy. These Anasazi newcomers — archaeologists have traced them to the mesas and canyons around Kayenta, Ariz., not far from the Hopi reservation — were distinctive in other ways. They liked to build with stone (the Hohokam used sticks and mud), and their kivas, like those they left in their homeland, are unmistakable: rectangular instead of round, with a stone bench along the inside perimeter, a central hearth and a sipapu, or spirit hole, symbolizing the passage through which the first people emerged from mother earth. “You could move this up to Hopi and not tell the difference,” said John A. Ware, the archaeologist leading the field trip, as he examined a Davis Ranch kiva. Finding it down here is a little like stumbling across a pagoda on the African veldt. For five days in late February, Dr. Ware, the director of the Amerind Foundation, an archaeological research center in Dragoon, Ariz., was host to 15 colleagues as they confronted the most vexing and persistent question in Southwestern archaeology: Why, in the late 13th century, did thousands of Anasazi abandon Kayenta, Mesa Verde and the other magnificent settlements of the Colorado Plateau and move south into Arizona and New Mexico? |

| Article |

A Question of Blame When Societies Fall As I pulled out of Tucson listening to an audiobook of Jared Diamond’s “Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed,” the first of a procession of blue-and-yellow billboards pointed the way to Arizona’s strangest roadside attraction, “The Thing?” The come-ons were slicker and brighter than those I remembered from childhood trips out West. But the destination was the same: a curio store and gas station just off the highway at a remote whistle stop called Dragoon, Ariz. Dragoon is also home to an archaeological research center, the Amerind Foundation, where a group of archaeologists, cultural anthropologists and historians converged in the fall for a seminar, “Choices and Fates of Human Societies.” What the scientists held in common was a suspicion that in writing his two best-selling sagas of civilization — the other is “Guns, Germs and Steel” — Dr. Diamond washed over the details that make cultures unique to assemble a grand unified theory of history. “A big-picture man,” one participant called him. For anthropologists, who spend their lives reveling in minutiae — the specifics and contradictions of human culture — the words are not necessarily a compliment. “Everybody knows that the beauty of Diamond is that it’s simple,” said Patricia A. McAnany, an archaeologist at Boston University who organized the meeting with her colleague Norman Yoffee of the University of Michigan. “It’s accessible intellectually without having to really turn the wattage up too much.” Dr. Diamond’s many admirers would disagree. “Guns, Germs and Steel” won a Pulitzer Prize, and Dr. Diamond, a professor of geography at the University of California, Los Angeles, has received, among many honors, a National Medal of Science. It is his ability as a synthesizer and storyteller that makes his work so compelling. For an hour I had listened as he, or rather his narrator, described how the inhabitants of Easter Island had precipitated their own demise by cutting down all the palm trees — for, among other purposes, transporting those giant statues — and how the Anasazi of Chaco Canyon and the Maya might have committed similar “ecocide.” |

| Column |

Bright Scientists, Dim Notions AT a conference in Cambridge, Mass., in 1988 called “How the Brain Works,” Francis Crick suggested that neuroscientific understanding would move further along if only he and his colleagues were allowed to experiment on prisoners. You couldn’t tell if he was kidding, and Crick being Crick, he probably didn’t care. Emboldened by a Nobel Prize in 1962 for helping uncoil the secret of life, Dr. Crick, who died in 2004, wasn’t shy about offering bold opinions — including speculations that life might have been seeded on Earth as part of an experiment by aliens. The notion, called directed panspermia, had something of an intellectual pedigree. But when James Watson, the other strand of the double helix, went off the deep end two Sundays ago in The Times of London, implying that black Africans are less intelligent than whites, he hadn’t a scientific leg to stand on. Since the publication in 1968 of his opinionated memoir, “The Double Helix,” Dr. Watson, 79, has been known for his provocative statements (please see “Stupidity Should be Cured, Says DNA Discoverer,” New Scientist, Feb. 28, 2003), but this time he apologized. Last week, uncharacteristically subdued, he announced his retirement as chancellor and member of the board of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island, where he had presided during much of the genetic revolution. Though the pronouncements are rarely so jarring, there is a long tradition of great scientists letting down their guard. Actors, politicians and rock stars routinely make ill-considered comments. But when someone like Dr. Watson goes over the top, colleagues fear that the public may misconstrue the pronouncements as carrying science’s stamp of approval. |

| Column |

Alex Wanted a Cracker, but Did He Want One? In “Oryx and Crake,” Margaret Atwood’s novel about humanity’s final days on earth, a boy named Jimmy becomes obsessed with Alex, an African gray parrot with extraordinary cognitive and linguistic skills. Hiding out in the library, Jimmy watches historical TV documentaries in which the bird deftly distinguishes between blue triangles and yellow squares and invents a perfect new word for almond: cork-nut. But what Jimmy finds most endearing is Alex’s bad attitude. As bored with the experiments as Jimmy is with school, the parrot would abruptly squawk, “I’m going away now,” then refuse to cooperate further. Except for the part about Jimmy and the imminent apocalypse (still, fingers crossed, a few decades away), all of the above is true. Until he was found dead 10 days ago in his cage at a Brandeis University psych lab, Alex was the subject of 30 years of experiments challenging the most basic assumptions about animal intelligence. He is survived by his trainer, Irene Pepperberg, a prominent comparative psychologist, and a scientific community divided over whether creatures other than human are more than automatons, enjoying some kind of inner life. Skeptics have long dismissed Dr. Pepperberg’s successes with Alex as a subtle form of conditioning — no deeper philosophically than teaching a pigeon to peck at a moving spot by bribing it with grain. But the radical behaviorists once said the same thing about people: that what we take for thinking, hoping, even theorizing, is all just stimulus and response. |

| Review |

Of Apples, String and, Well.... EverythingEndless Universe Beyond the Big Bang Paul J. Steinhardt and Neil Turok Doubleday: 286 pp., $24.95  OUTSIDE the Great Gate of Trinity College, Cambridge, is a tree reputed to be descended from the one that dropped the apple on Isaac Newton's head. The result of the concussion, the legend goes, was Newton's law of universal gravitation: The same force that pulls things to Earth also binds the planets around the sun. So began an era of cosmic mergers and acquisitions that led, three centuries later, to Stephen Hawking's famous prediction that the end of physics -- the Theory of Everything -- was in sight Hawking, as his press agents never tire of reminding us, holds Newton's old chair as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge University. By the time he assumed the post, an all-encompassing physics indeed seemed at hand. Electricity had been united with magnetism, and electromagnetism with the weak force that causes nuclear decays. For their next act, physicists planned to combine this electroweak force with the strong nuclear force that glues quarks together. That would still leave gravity, but Hawking bet, in his inaugural Lucasian lecture in April 1980, that by the year 2000 it too would be absorbed into the mix. All these fundamental forces would be reduced to facets of a single phenomenon -- supergravity -- present at the moment of creation. Sitting in the audience that day was a graduate student, Neil Turok, who went on to get a PhD in theoretical physics. He didn't suspect at the time that he would be swept up by another convergence -- between his newly chosen field and cosmology. It was a natural connection: Testing an idea like supergravity required a particle accelerator literally the size of the universe -- and the "experiment" had already been done: In the searing temperatures of the Big Bang, all the forces would still have been fused together. Figure out the Bang and you could reverse-engineer the Theory of Everything. That's not how things turned out. In "Endless Universe: Beyond the Big Bang," Turok and Paul J. Steinhardt, a Princeton physicist, describe how they devoted years to the quest, only to find themselves veering from the pack with a new theory -- a radical model of the universe in which there is no beginning explosion but, rather, an endless cycle of cosmic thunderclaps. |

| Review |

Meta Physicists As though their knowledge of the quantum secrets came with the power of prophecy, some three dozen of Europe’s best physicists ended their 1932 meeting in Copenhagen with a parody of Goethe’s “Faust.” Just weeks earlier, James Chadwick had discovered neutrons — the bullets of nuclear fission — and before long Enrico Fermi was shooting them at uranium atoms. By the time of the first nuclear explosion a little more than a decade later in New Mexico, the idea of physics as a Faustian bargain was to its makers already a cliché. Robert Oppenheimer, looking for a sound bite, quoted Vishnu instead: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Innocent of all that lay before them, the luminaries gathering at Niels Bohr’s Institute for Theoretical Physics were in a whimsical mood. Werner Heisenberg, Paul Dirac and Lise Meitner were there. Max Delbrück, the young scientist charged with writing the spoof — it happened to be the centennial of Goethe’s death — couldn’t resist depicting Bohr himself as the Lord Almighty and the acerbic Wolfgang Pauli as Mephistopheles. They were perfect choices. The avuncular Bohr, with his inquisitive needling, had presided over the quantum revolution, revealing the strange workings within atoms, while the skeptical Pauli, who famously signed his letters “The Scourge of God,” could always be counted on for a sarcastic comment. (“What Professor Einstein has just said is not so stupid.”) Faust, who in the legend sells his soul for universal knowledge, was recast as a troubled Paul Ehrenfest, the Austrian physicist who despaired of ever understanding this young man’s game in which particles were just smears of probability. |

| Article |

God Is in the DendritesCan “Neurotheology” Bridge the Gap between Religion and Science?  Looking back, it was the intellectual high point of my summer: Ten science and religion reporters sitting inside the divinity building at Cambridge University, contemplating the essence of a raisin. As the hypnotic voice of the speaker, an expert on Buddhist meditation, lulled us from the here and now, I placed the wrinkly thing on my tongue, exploring its peaks and valleys until, all of a sudden, I broke through the linguistic cellophane. The raisin ceased to be a raisin or anything with a name. It had no history as a fruit grown on a vine and shipped to market; it evoked no memories of the little Sun-Maid boxes my mother packed in my lunch pail or of a particularly good glass of cabernet sauvignon. It just was. My colleagues–we were in England for a journalism fellowship sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation, which hopes to find God in science–were having their own quiet epiphanies. After days of talks by physicists and theologians seeking cosmological justification for their spiritual beliefs, the close encounter with the raisin brought us back to earth. God was not to be found in the perfect wheeling of the cosmos, the quantum ambiguity of the atom, or the fortuity of the Big Bang, but in the electrical crackling of the human brain. If recent findings in “neurotheology” hold up, our meditating neurons, locked in the state called mindfulness, were radiating gamma waves at about 40 cycles per second, beating against the 50-hertz hum of the fluorescent lights. At the same time, parts |

| Review |

Dancing With the Starsby  In June 1948, as Jack Kerouac was recovering from another of the amphetamine-fueled joy rides immortalized in On the Road, Freeman Dyson, a young British physicist studying at Cornell, set off on a road trip of a different kind. Bound for Albuquerque with the loquacious Richard Feynman, the Neal Cassady of physics, at the wheel, the two scientists talked nonstop about the morality of nuclear weapons and, when they had exhausted that subject, how photons dance with electrons to produce the physical world. The hills and prairies that Dyson, still new to America, was admiring from the car window, the thunderstorm that stranded him and Feynman overnight in Oklahoma–all of nature's manifestations would be understood on a deeper level once the bugs were worked out of an unproven idea called quantum electrodynamics, or QED. Dyson recounted the journey years later in Disturbing the Universe, contrasting Feynman's Beat-like soliloquies on particles and waves with the mannered presentations (“more technique than music”) he heard later that summer from the Harvard physicist Julian Schwinger. On a Greyhound bus crossing Nebraska–Dyson had fallen in love with the American highway–he had an epiphany: his two colleagues were talking, in different languages, about the same thing. It was a pivotal moment in the history of physics. With their contrasting visions joined into a single theory, Feynman, Schwinger and the Japanese scientist Sin-Itiro Tomonaga were honored in 1965 with a Nobel Prize, one that some think Dyson deserved a piece of. In The Scientist as Rebel, a new collection of essays (many of them reviews first published in The New York Review of Books), he sounds content with his role as a bridge builder. “Tomonaga and Schwinger had built solid foundations on one side of a river of ignorance,” he writes. “Feynman had built solid foundations on the other side, and my job was to design and build the cantilevers reaching out over the water until they met n the middle.” Drawing on this instinct for unlikely connections, Dyson has become one of science's most eloquent interpreters. From his perch at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, he followed Disturbing the Universe, a remembrance of physics in the making, with Infinite in All Directions, his exuberant celebration of the universe, and other books like Weapons and Hope, |

| Review |

A New Journey into Hofstadter's MindThe eternal golden braid emerges as a strange loop.  To get into a properly loopy mind-set for Douglas R. Hofstadter's new book on consciousness, I plugged a Webcam into my desktop computer and pointed it at the screen. In the first instant, an image of the screen appeared on the screen and then the screen inside the screen. Cycling round and round, the video signal rapidly gave rise to a long corridor leading toward a patch of shimmering blue, beckoning like the light at the end of death's tunnel. Giving the camera a twist, I watched as the regress of rectangles took on a spiraling shape spinning fibonaccily deeper into nowhere. Somewhere along the way a spot of red--a glint of sunlight, I later realized--became caught in the swirl, which slowly congealed into a planet of red continents and blue seas. Zooming in closer, I explored a surface that was erupting with yellow, orange and green volcanoes. Like Homer Simpson putting a fork inside the microwave, I feared for a moment that I had ruptured the very fabric of space and time. In I Am a Strange Loop, Hofstadter, a cognitive and computer scientist at Indiana University, describes a more elaborate experiment with video feedback that he did many years ago at Stanford University. By that time he had become obsessed with the paradoxical nature of Gödel's theorem, with its formulas that speak of themselves. Over the years this and other loopiness--Escher's drawings of hands drawing hands, Bach's involuted fugues--were added to the stew, along with the conviction that all of this had something to do with consciousness. What finally emerged, in 1979, was Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, one of the most captivating books I have ever read. I still remember standing in the aisle of a bookstore in Washington, D.C., where I had just finished graduate school, devouring the pages. GEB, as the author calls it, is not so much a "read" as an experience, a total immersion into Hofstadter's mind. It is a great place to be, and for those without time for the scenic route, I Am a Strange Loop pulls out the big themes and develops them into a more focused picture of consciousness. |

| Article |

Getting a Rational Grip on ReligionIs religion a fit subject for scientific scrutiny?  If nowhere else, the dead live on in our brain cells, not just as memories but as programs--computerlike models compiled over the years capturing how the dearly departed behaved when they were alive. These simulations can be remarkably faithful. In even the craziest dreams the people we know may remain eerily in character, acting as we would expect them to in the real world. Even after the simulation outlasts the simulated, we continue to sense the strong presence of a living being. Sitting beside a gravestone, we might speak and think for a moment that we hear a reply. In the 21st century, cybernetic metaphors provide a rational grip on what prehistoric people had every reason to think of as ghosts, voices of the dead. And that may have been the beginning of religion. If the deceased was a father or a village elder, it would have been natural to ask for advice--which way to go to find water or the best trails for a hunt. If the answers were not forthcoming, the guiding spirits could be summoned by a shaman. Drop a bundle of sticks onto the ground or heat a clay pot until it cracks: the patterns form a map, a communication from the other side. These random walks the gods prescribed may indeed have formed a sensible strategy. The shamans would gain in stature, the rituals would become liturgies, and centuries later people would fill mosques, cathedrals and synagogues, not really knowing how they got there. With speculations like these, scientists try to understand what for most of the world's population needs no explanation: why there is this powerful force called religion. It is possible, of course, that the world's faiths are triangulating in on the one true God. But if you forgo that leap, other possibilities arise: Does banding together in groups and acting out certain behaviors confer a reproductive advantage, spreading genes favorable to belief? Or are the seeds of religion more likely to be found among the memes--ideas so powerful that they leap from mind to mind? |

| Article |

A Free-for-All on Science and Religion Maybe the pivotal moment came when Steven Weinberg, a Nobel laureate in physics, warned that “the world needs to wake up from its long nightmare of religious belief,” or when a Nobelist in chemistry, Sir Harold Kroto, called for the John Templeton Foundation to give its next $1.5 million prize for “progress in spiritual discoveries” to an atheist–Richard Dawkins, the Oxford evolutionary biologist whose book The God Delusion is a national best-seller. Or perhaps the turning point occurred at a more solemn moment, when Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York City and an adviser to the Bush administration on space exploration, hushed the audience with heartbreaking photographs of newborns misshapen by birth defects–testimony, he suggested, that blind nature, not an intelligent overseer, is in control. Somewhere along the way, a forum this month at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, Calif., which might have been one more polite dialogue between science and religion, began to resemble the founding convention for a political party built on a single plank: in a world dangerously charged with ideology, science needs to take on an evangelical role, vying with religion as teller of the greatest story ever told. Carolyn Porco, a senior research scientist at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo., called, half in jest, for the establishment of an alternative church, with Dr. Tyson, whose powerful celebration of scientific discovery had the force and cadence of a good sermon, as its first minister. |

| Article |

Scientists on ReligionTheist and materialist ponder the place of humanity in the universe.  Ten years after his death in 1996, science writer Walter Sullivan's byline occasionally still appears in the New York Times on obituaries of important physicists, as though he were beckoning them to some quantum-mechanical heaven. This is not a case of necromancy–the background material for Times obits is often written in advance and stored. If the dead really did communicate with the living, that would be a scientific event as monumental as the discovery of electromagnetic induction, radioactive decay or the expansion of the universe. Laboratories and observatories all over the world would be fiercely competing to understand a new phenomenon. One can imagine Mr. Sullivan, the ultimate foreign correspondent, eagerly reporting the story from the other side. Light is carried by photons, gravity by gravitons. If there is such a thing as spiritual communication, there must be a means of conveyance: some kind of “spiritons”–ripples, perhaps, in one of M Theory's leftover dimensions. Some theologians might scoff at that remark, yet there has been a resurgence in recent years of "natural theology"–the attempt to justify religious teachings not through faith and scripture but through rational argument, astronomical observations and even experiments on the healing effects of prayer. The intent is to prove that, Carl Sagan be damned, we are not lost among billions and billions of stars in billions and billions of galaxies, that the universe was created and is sustained for the benefit of God's creatures, the inhabitants of the third rock from the sun. In God's Universe, Owen Gingerich, a Harvard University astronomer and science historian, tells how in the 1980s he was part of an effort to produce a kind of anti-Cosmos, a television series called Space, Time, and God that was to counter Sagan's "conspicuously materialist approach to the universe." The program never got off the ground, but its premise survives: that there are two ways to think about science. You can be a theist, believing that behind the veil of randomness lurks an active, loving, manipulative God, or you can be a materialist, for whom everything is matter and energy interacting within space and time. Whichever metaphysical club you belong to, the science comes out the same. |

| Review |

Favored by the GodsHappiness, according to current scientific thinking, depends less on our circumstances than on our genetic endowment  The sky was smeared with the lights from the midway, spinning, blinking, beckoning to risk takers, but I decided to go for a different kind of thrill: Ronnie and Donnie Galyon, the Siamese Twins, were at the Minnesota State Fair. Feeling some guilt, I bought my ticket and cautiously approached the window of the trailer they called home. Thirty years old, joined at the stomach, they were sitting on a sofa, craning their necks to watch television. Twenty-five years later I am still struck by this dizzying conjunction of the grotesque and the mundane. Trying to project myself into their situation--a man with two heads, two men with one body--I felt only sickness, horror and a certainty that I would rather be dead. Yet there they were, traveling from town to town, leading some kind of life. When we try to envision another's happiness, we suffer from arrogance and a poverty of imagination. In 1997, when science writer Natalie Angier interviewed Lori and Reba Schappell, connected at the back of the head and sporting different hairdos, each insisted that she was basically content. "There are good days and bad days--so what?" Reba said. "This is what we know. We don't hate it. We live it every day." Lori was as emphatic: "People come up to me and say, 'You're such an inspiration. Now I realize how minor my own problems are compared to yours.' But they have no idea what problems I have or don't have, or what my life is like.'' Three recent books--two by scientists and one by a historian--take on the quest for the good life, in which common sense and the received wisdom of the ages is increasingly confronted by findings from psychology, neuroscience and genetics: |

| Article |

Science and Religion, Still Worlds ApartOne October day in 1947, the director of the local bank in Marksville, La., woke to find that hundreds of fish had fallen from the sky, landing in his backyard. People walking to work that day were struck by falling fish, and an account of the incident by a researcher for the state's wildlife and fisheries department later found its way into the annals of scientific anomalies – phenomena waiting to be understood. Fish falls have also been reported in Ethiopia and other parts of the world. Whether they are hoaxes, hallucinations or genuine meteorological events – maybe fish can be swept up by a waterspout and transported – scientists are disposed to assume a physical explanation. The same kind of scrutiny is accorded to miracles – fishes and loaves multiplying to feed the masses and the like. But as two research papers published this month suggest, looking to science to prove a miracle is a losing proposition, for believers and skeptics. |

| Article |

War of the Worlds The daddy longlegs clinging vertically to my bathroom wall is a marvel of airy symmetry, its tiny head perched delicately at the center of eight arching limbs. A moment later, struck by the back of my hand, it lies crumpled on the floor. I'm sorry, but I don't like spiders in the house. In fact, as I learn the next morning, it wasn't a spider I killed, an Araneida, but a member of a parallel order, Phalangida—one that lives by eating spiders, including the annoying little ones that bite. My reflexive action was stupidly self-defeating. But my remorse runs deeper. I feel guilty for destroying this elegant arrangement of carbon molecules, and I can't quite understand why. I don't feel a thing when I pull horsetail and cheat grass from our meadow or massacre a swarm of box elder beetles with laundry soap. I am glad when the cats kill a grasshopper or a mouse; indifferent if their prey is a sparrow; sad if it is a hummingbird. There is no definable moral calculus here. All organisms, I know, are nothing more or less than intricate, intertwined chemistry, products of an evolutionary process that is purposeless and blind. Yet I find myself behaving sometimes as though the world were crawling with spirits. I, the materialist, am making godlike judgments as to what has a “soul,” whatever that means, and what deserves to live or die. A believer might say I am wrestling with something “spiritual.” I cringe when I hear the word, coming, with all its musty connotations, from the Latin spiritus, meaning “of breathing” or “of wind.” People once thought invisible beings swooped through the trees, bending the branches, propelling leaves and dust. They believed the rhythmic inhalation of these spirits—respiration—animated the body (from the Greek anemos, which also means wind). |

| Review |

EnigmaticThe Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer, by David Leavitt  Maybe it's because I already knew the story - about the tragic genius who revolutionized mathematics, helped the British crack secret Nazi codes and died after biting into a poisoned apple. Or maybe I was just in the mood for fiction. For some reason, about halfway through David Leavitt's short, readable life of Alan Turing, I put the book aside for a few days and turned instead to his most recent novel, "The Body of Jonah Boyd." It is actually a novel within a novel, ending with a self-referential twist that made me wonder whether Leavitt had been inspired by Turing's dizzying proof about undecidability in mathematics, in which a computer tries to swallow its own tail. Turing was a fellow at King's College, Cambridge, in 1936, when he confronted what might be called the mathematician's nightmare: the possibility of blindly devoting your life to what, unbeknownst to anyone but God, is an unsolvable problem. If only there were a way to know beforehand, a procedure for sifting out and discarding the uncrackable nuts. Turing's stroke of genius was to recast the issue - mathematicians call it the decision problem - in mechanical terms. A theorem and the instructions for proving it, he realized, could be thought of as input for a machine. If there was a solution, Turing's imaginary device would eventually come to a stop and print the answer. Otherwise it would grind away forever. Although it was not his primary intention, he had discovered, in passing, the idea of the programmable computer. Now all that he needed to identify undecidable problems was a method for predicting in advance which programs would get stuck in infinite loops. But that would require examining them with another program, and how would you know that it wouldn't get stuck without vetting it with a third program, ad infinitum? Like a novel about a novelist writing a novel, the dream of mathematical infallibility went |

| Article |

For the Anti-Evolutionists, Hope in High PlacesIdeas and Trends  Except for the robes and the fact that each is addressed as "His Holiness," it would be hard to find much in common between Pope Benedict XVI and Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama. Yet both have recently expressed an unhappiness with evolutionary science that would be a comfort to the Pennsylvania school board now in a court fight over its requirement that the hypothesis of a creator be part of the science curriculum. It's not just fundamentalist Protestants who have difficulty with the idea that life arose entirely from material causes. Look East or West and you can detect the rumblings from an irreconcilable divide between science and religion, with one committed to a universe of matter and energy and the other to the existence of something extra, a spiritual realm. Sometimes compared to the Scopes "monkey trial" of 1925, Kitzmiller et al. v. Dover Area School District opened last week in Federal District Court in Harrisburg with scientists making the usual arguments against intelligent design - which holds that the complexity of biological organisms is evidence of a creator. Opponents say they doubt that the theory's supporters, like the Discovery Institute in Seattle, are talking about a smart gas cloud or a 10th-dimensional teenager simulating the universe on his Xbox. The American Civil Liberties Union, which filed suit against the Dover district, considers intelligent design a Trojan horse to introduce religion into public schools. This time the anti-evolutionists won't be relying on the fundamentalist oratory moviegoers heard from the Fredric March character in "Inherit the Wind." Instead, the arguments may not sound so different from what one would hear if either the pope or the Dalai Lama were called to the stand. Neither of these men believes that a religious text, whether the Bible or the Diamond Sutra, should be given a strictly literal reading. Yet they share with evangelicals an aversion to the notion that life emerged blindly, without supernatural guidance. Particularly offensive to them is the theory, part of the biological mainstream, that the engine of evolution is random |

| Article |

Agreeing Only to Disagree on God's Place in Science It was on the second day at Cambridge that enlightenment dawned in the form of a testy exchange between a zoologist and a paleontologist, Richard Dawkins and Simon Conway Morris. Their bone of contention was one that scholars have been gnawing on since the days of Aquinas: whether an understanding of the universe and its glories requires the hypothesis of a God. The speakers had been invited, along with a dozen other scientists and theologians, to address the 10 recipients of the first Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Fellowships in Science and Religion. Each morning for two weeks in June, we walked across the Mathematical Bridge, spanning the River Cam, and through the medieval courtyards of Queens College to the seminar room. We were there courtesy of the John Templeton Foundation, whose mission is “to pursue new insights at the boundary between theology and science,” overcoming what it calls “the flatness of a purely naturalistic, secularized view of reality.” On matters scientific, Dr. Dawkins, who came from Oxford, and Dr. Conway Morris, a Cambridge man, agreed: The richness of the biosphere, humanity included, could be explained through natural selection. They also agreed, contrary to the writings of Stephen Jay Gould, that evolution is not a crapshoot. If earth's history could be replayed like a video cassette, the outcome would be somewhat different, but certain physical constraints would favor the eventual appearance |

| Article |

The Universe in a Single AtomReason and Faith  It was his subtitle that bothered me. Spirituality is about the ineffable and unprovable, science about the physical world of demonstrable fact. Faced with two such contradictory enterprises, divergence would be a better goal. The last thing anyone needs is another attempt to contort biology to fit a particular religion or to use cosmology to prove the existence of God. But this book offers something wiser: a compassionate and clearheaded account by a religious leader who not only respects science but, for the most part, embraces it. "If scientific analysis were conclusively to demonstrate certain claims in Buddhism to be false, then we must accept the findings of science and abandon those claims," he writes. No one who wants to understand the world "can ignore the basic insights of theories as key as evolution, relativity and quantum mechanics." That is an extraordinary concession compared with the Christian apologias that dominate conferences devoted to reconciling science and religion. The "dialogues" implicitly begin with nonnegotiables - "Given that Jesus died on the cross and was bodily resurrected into heaven…" - then seek scientific justification for what is already assumed to be true. |

| Article |

Star Wars: Episodes 1 and 2 The object of the game is to figure out how the universe works by watching tiny lights move across the sky. The answers must be expressed in numbers -- that is the cardinal rule -- but sometimes passions take over, leaving the history of astrophysics bloodied from clashes among some of the smartest people in the world. Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar -- associates always called him Chandra -- was 19 when, on a boat from India to Britain, he had an idea whose consequences seemed absurd. Scientists suspected that when a star finally gave out, it would be squashed by its own gravity, growing smaller and denser until it died. But what if a star was so massive it was unable to stop collapsing? As it contracted its gravity would keep increasing until, Chandra concluded, it swallowed itself and disappeared -- a black hole. In the next few years, at Cambridge University, he showed mathematically how this would happen, and in 1935 (he was 24) presented his case at a meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society. The proof was in the equations, but the fight had barely begun. In ''Empire of the Stars: Obsession, Friendship, and Betrayal in the Quest for Black Holes,'' Arthur I. Miller, a British philosopher of science, describes the scene as Chandra's older colleague Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington rises to the podium and savages the black hole theory. To Eddington, as brash and overbearing as Chandra was reserved and polite, the theory was ''stellar buffoonery,'' and so great was his prestige that five decades passed before Chandra, then at the University of Chicago, was vindicated by a Nobel Prize. |