Zeeya Merali

Zeeya Merali has written articles across a range of scientific subjects for Scientific American, Nature, New Scientist, and Discover. A freelance journalist and author, she has published two textbooks in collaboration with National Geographic and is now working on her first popular physics book. Her documentary, Aperture Fever, about amateur astronomy, was broadcast on The History Channel, UK, in 2008. She has also worked on the forthcoming Nova television series The Fabric of the Cosmos.

| Column |

The Priest-Physicist Who Would Marry Science to ReligionJohn Polkinghorne leads a disparate group of scientists on the controversial search for God within the fractured logic of quantum physics.  When he describes his line of work, John Polkinghorne jests, he encounters "more suspicion than a vegetarian butcher." For the particle physicist turned Anglican priest, dissonance comes with the territory. Science parses the concrete: the structure of the atom and the workings of the brain. Religion confronts the intangible: questions about ethics and the purpose of life. Taken literally, the biblical story of Genesis contradicts modern cosmology and evolutionary biology in full. Yet 21 years ago, in a move that made many eyes roll, Polkinghorne began working to unite the two sides by seeking a mechanism that would explain how God might act in the physical world. Now that work has met its day of reckoning. At a series of meetings at Oxford University last July and September, timed to celebrate Polkinghorne’s 80th birthday, physicists and theologians presented their answers to the questions he has so relentlessly pursued. Do any physical theories allow room for God to influence human actions and events? And, more controversially, is there any concrete evidence of God’s hand at work in the physical world? Sitting with Polkinghorne on the grounds of St. Anne’s College, Oxford, it is difficult to regard the jovial gentleman with suspicion. Oxford has been dubbed the "city of dreaming spires," and Polkinghorne is as quintessentially English as the university’s famed architecture, with college towers and church spires standing side by side. The bespectacled elder statesman of British science walks with a stick and wears hearing aids in both ears. But he retains a spring in his step and a quick wit. ("He will charm you in conversation, as long as you get him in his better ear," a colleague says.) Polkinghorne’s dual identity emerged early. He grew up in a devout Christian family but was always drawn to science, and in graduate school he became a particle physicist because, he explains modestly, he was also "quite good at mathematics." His scientific pedigree is none too shabby. He worked with Nobel laureate Abdus Salam while earning a doctorate in theoretical physics from Cambridge University, where he later held a professorial chair. One of his students, Brian Josephson, went on to win a share of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1973. Polkinghorne himself joined Nobel laureate Murray Gell-Mann in research that led to the discovery of the quark, the building block of atoms. But in 1979, after 25 years in the trenches, Polkinghorne decided that his best days in physics were behind him. "I felt I had done my bit for the subject, and I’d go do something else," he says. That is when he left his academic position to be ordained. |

| Article |

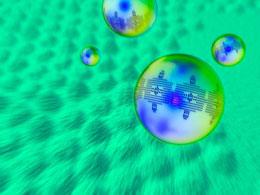

Connect the Quantum Dots for a Full-Colour ImageNanocrystal display could be used in high-resolution, low-energy televisions.  Ink stamps have been used to print text and pictures for centuries. Now, engineers have adapted the technique to build pixels into the first full-colour 'quantum dot' display — a feat that could eventually lead to televisions that are more energy-efficient and have sharper screen images than anything available today. Engineers have been hoping to make improved television displays with the help of quantum dots — semiconducting crystals billionths of a metre across — for more than a decade. The dots could produce much crisper images than those in liquid-crystal displays, because quantum dots emit light at an extremely narrow, and finely tunable, range of wavelengths. The colour of the light generated depends only on the size of the nanocrystal, says Byoung Lyong Choi, an electronic engineer at the Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology in Yongin, South Korea. Quantum dots also convert electrical power to light efficiently, making them ideal for use in energy-saving lighting and display devices. Easier said than done Attempts to commercialize the technology have been hampered because it is difficult to make large quantum-dot displays without compromising the quality of the image. The dots are usually layered onto the material used to make the display by spraying them onto the surface — a technique similar to that of an ink-jet printer. But the dots must be prepared in an organic solvent, which "contaminates the display, reducing the brightness of the colours and the energy efficiency", says Choi. Choi and his colleagues have now found a way to bypass this obstacle, by turning to a more old-fashioned printing technique — details of which appear today in Nature Photonics1. The team used a patterned silicon wafer as an 'ink stamp' to pick up strips of dots made from cadmium selenide, and press them down onto a glass substrate to create red, green and blue pixels without using a solvent. |

| Column |

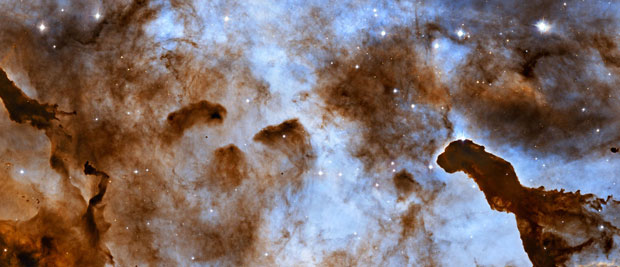

Harvest Moons and the Seeds of Our FaithHow the fall equinox, and the science of ancient astronomy, helped shape religions.  Next Wednesday heralds the official end of summer—the autumnal equinox —when the length of day and night are equal (circa 11:09 p.m. ET). In the 21st century, this astronomical event is little more than a passing curiosity. But rewind by about three millennia to the time of the ancient Babylonians, and the autumnal equinox marked the start of the "minor new year." Not only did celestial events define sacred festivals. Conversely, religion powered the development of astronomy, the first science. Today, science and religion are often thought to be very different, unconnected disciplines. But looking back at our ancient past, we see that the development of religion and early science have really gone hand-in-hand, shaping some of the characteristics of mainstream religion in ways we may not realize. For instance, while the Babylonians celebrated their "main new year" in the spring, their tradition of having a minor autumnal new year has carried over into both mainstream religion and secular practice. Nick Campion, a historian of cultural astronomy at the University of Wales, notes two echoes of ancient autumn observances today. "It's a custom inherited by Jews—hence Rosh Hashanah," he told me, "while the beginning of the academic year in autumn is a secular legacy." The Babylonians made meticulous records of celestial events. To them, as to many ancient civilizations, the sky was thought to be the writing pad of the gods, while the stars and planets were the ink used to communicate divine messages. Through today's lens, the practices of star-gazing Babylonian priests may appear to be based mostly in superstition. Each night they searched the sky for omens sent by the great god Marduk or one of his entourage of lesser deities. Unexpected wanderings of the planets might foreshadow a poor harvest in the village, while the early risings of the moon could portend malformed births. By far the worst harbinger was a lunar eclipse, which signaled that the gods were angry with the king and called for his death. Much early astronomy dealt with developing techniques to predict these omens, allowing crucial time for pre-emptive prayers and rituals to ward off misfortune. Despite being tied to religious ritual (and often to gruesome sacrifice), the work of these priests marks the beginnings of science, says John Steele, a historian of ancient astronomy at Brown University. "They were making mathematical predictions based on empirical observations, which is astronomy by definition," he says. |

| Article |

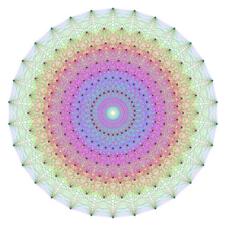

Rummaging for a Final TheoryUnifying gravity and particle physics may come down to an old approach from the 1960s.  Turning the clock back by half a century could be the key to solving one of science’s biggest puzzles: how to bring together gravity and particle physics. At least that is the hope of researchers advocating a back-to-basics approach in the search for a unified theory of physics. In July mathematicians and physicists met at the Banff International Research Station in Alberta, Canada, to discuss a return to the golden age of particle physics. They were harking back to the 1960s, when physicist Murray Gell-Mann realized that elementary particles could be grouped according to their masses, charges and other properties, falling into patterns that matched complex symmetrical mathematical structures known as Lie ("lee") groups. The power of this correspondence was cemented when Gell-Mann mapped known particles to the Lie group SU(3), exposing a vacant position indicating that a new particle, the soon to be discovered "Omega-minus," must exist. During the next few decades, the strategy helped scientists to develop the Standard Model of particle physics, which uses a combination of three Lie groups to weave together all known elementary particles and three fundamental forces: electromagnetism; the strong force, which holds atomic nuclei together; and the weak force, which governs radioactivity. It seemed like it would only be a matter of time before physicists found an overarching Lie group that could house everything, including gravity. But such attempts came unstuck because they predicted phenomena not yet seen in nature, such as the decay of protons, says physicist Roberto Percacci of the International School for Advanced Studies in Trieste, Italy. The approach fell out of favor in the 1980s, as other candidate unification ideas, such as string theory, became more popular. But inspired by history, Percacci developed a model with Fabrizio Nesti of the University of Ferrara in Italy and presented it at the meeting. In the model, gravity is contained within a large Lie group, called SO(11,3), alongside electrons, quarks, neutrinos and their cousins, collectively known as fermions. Although the model cannot yet explain the behavior of photons or other force-carrying particles, Percacci believes it is an important first step. |

| Article |

Physicists Get Political Over HiggsA storm is brewing round the scientists in line to win the Nobel prize for predicting the elusive particle.  It hasn't even been found yet, but the elusive Higgs particle is already generating controversy. As feelings run high over a recent conference in France, the particle physics community are split over who should get credit out of the six theoretical physicists who developed the mechanism behind its existence. The Higgs particle is predicted to exist as part of the mechanism believed to give particles their mass, and is the only piece of the Standard Model of particle physics that remains to be discovered. Physicists at both the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, Europe's premier particle physics laboratory near Geneva in Switzerland, and the Tevatron accelerator in Batavia, Illinois, recently voiced their expectation that the particle could well be detected within the next few years. This gave new urgency not only to the race to find the particle, but also to establishing authorship of the ideas behind it. As John Ellis, a particle physicist based at CERN, acknowledges: "Let's face it, a Nobel prize is at stake." The authorship question is fraught because the mechanism was developed independently by three groups within a matter of weeks in 1964. First up were Robert Brout and François Englert in Belgium, followed by Peter Higgs in Scotland, and finally Tom Kibble in London, along with his colleagues in the United States, Gerald Guralnik (at the time in London) and Carl R. Hagen. "There are six people who developed the mechanism in quick succession and who hold a legitimate claim to credit for it," says particle physicist Frank Close at the University of Oxford, UK. |

| Article |

UK Climate Data Were Not Tampered WithScience sound despite researchers' lack of openness, inquiry finds.  The "rigour and honesty" of scientists embroiled in the climate change e-mail affair are "not in doubt" — according to an independent review of the matter released today. However, the scientists have been criticized for a lack of openness that risked "the credibility of UK climate science". In November 2009, more than 1,000 e-mails and documents were hacked from the Climatic Research Unit (CRU) at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK, and posted on the Internet. They prompted allegations from climate-change sceptics that CRU scientists withheld, concealed and manipulated data in an attempt to boost the case for human-induced climate change. The review, led by Muir Russell, the former vice-chancellor of the University of Glasgow, UK, was charged with investigating the scientists' behaviour. In a 160-page report, the five-person review committee says that it found no evidence of malicious intent, but rather a "consistent pattern of failing to display the proper degree of openness" both among researchers and in the university's leadership in handling the affair. "They were unhelpful in response to legitimate requests," says Russell, adding that scientists "need to have in the forefront of their minds the importance of the credibility of the knowledge base they are generating and of not losing public trust". The review has not impressed vocal climate-change critics, such as Andrew Montford who maintains the blog Bishop Hill. "I find the review pretty appalling," he says. "I do not think they have gone deep enough." Under scrutinyIn exploring allegations that the CRU withheld or tampered with data, the committee scrutinized e-mails concerning the selection of weather-station data in research published in Nature1, led by former CRU director, Phil Jones — who stepped down from his position while the investigation was under way. To check the paper's conclusion that rising temperatures could not be caused by the local "urban heat island effect" — in which cities tend to be warmer than surrounding rural areas — but should rather be attributed to global climate change, the review panel downloaded the source data directly from publicly accessible sites. "It became very clear, very early on that anyone can get the data...it took us literally minutes to download," says committee-member Peter Clarke, a professor of physics at the University of Edinburgh, UK. |

| Article |

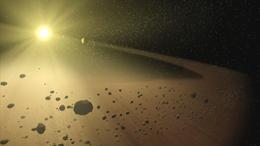

Asteroid Ice Hints at Rocky Start to Life on EarthCool discovery suggests asteroids brought water and organic material.  A slushy cocktail of water-ice and organic materials has been directly detected on the surface of an asteroid for the first time. The finding strengthens the theory that asteroids delivered the ingredients for Earth's oceans and life, and could make astronomers rethink conventional models for how the Solar System evolved. It has long been thought that asteroids, which lie in a belt between Mars and Jupiter, are rocky bodies that sit too close to the Sun to retain ice. By contrast, comets, which form further out beyond Neptune, are ice-rich bodies that develop distinctive tails of vaporized gas and dust when they approach the Sun. However, this distinction was blurred in 2006 by the discovery of small objects with comet-like tails in the asteroid belt1, says astronomer Andrew Rivkin of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. To investigate the composition of these 'main-belt comets', Rivkin and his colleague Joshua Emery, of the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, turned the infra-red telescope at Mauna Kea, Hawaii, onto the asteroid 24 Themis — the parent body from which two of the smaller comet-like asteroids observed in 2006 were chipped. Emery and Rivkin took seven measurements of 24 Themis over a period of six years, each time looking at a different face of the asteroid as it travelled around its orbit. They consistently found a band in the absorption spectrum of light reflected from its surface that indicated the presence of grains coated in water ice, as well as the signature of carbon-to-hydrogen chemical bonds — as found in organic materials. Rivkin and Emery's work is published in this week's Nature2. "Astronomers have looked at dozens of asteroids with this technique, but this is the first time we've seen ice on the surface and organics," says Rivkin. The result was independently confirmed by a team led by Humberto Campins at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. He and his colleagues observed 24 Themis for 7 hours one night, as it almost fully rotated on its axis. "Between us, we have seen the asteroid from almost every angle and we see global coverage," says Campins. He and his team also publish their findings in this week's Nature3. Julie Castillo-Rogez, an astrophysicist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, describes the findings as "huge". "This answers the long-term question of whether there is free water in the asteroid belt," she says. |

| Article |

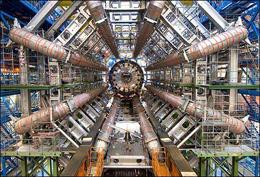

Physics: The Large Human ColliderSocial scientists have embedded themselves at CERN to study the world's biggest research collaboration. Zeeya Merali reports on a 10,000-person physics project.  "I am here to watch you." So began anthropologist Arpita Roy when introducing herself in 2007 to a roomful of particle physicists. At the time, those scientists were racing to finish work on the world's biggest machine, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, Europe's high-energy physics laboratory near Geneva, Switzerland. The LHC carries the hopes of generations of physicists, who have designed it to reach energies never before achieved in a collider and — possibly — to produce a zoo of particles new to science. But the LHC is also a huge human experiment, bringing together an unprecedented number of scientists. So in recent years, sociologists, anthropologists, historians and philosophers have been visiting CERN to see just how these densely packed physicists collide, ricochet and sometimes explode. "The LHC allows a unique sociological study of how an experiment develops in real time: how scientists form opinions, make technical decisions and circulate knowledge in such a big project," says Arianna Borrelli, a particle physicist and philosopher of physics at the University of Wuppertal in Germany. Sergio Bertolucci, CERN's research director, is acutely aware of the importance of cohesive collaboration. "This is an incredible social experiment," he says, noting that roughly 10,000 physicists around the world are taking part in the LHC experiments and 2,250 of them are employed at CERN. Just reflecting on the size of the collaboration he co-manages makes Bertolucci's head ache. "Imagine the organization needed when 3,000 people all want to know in advance if they can go home for Christmas," he says. Managers at CERN have endured a series of headaches since the LHC powered up in September 2008. A little more than a week after the collider came online, a faulty electrical coupling caused an explosion that brought the project to a halt for 14 months. That setback demoralized the scientists at CERN, particularly the graduate students, who worried about the fate of their degrees, says Roy. A graduate student herself, from the University of California, Berkeley, Roy has been camped out at CERN on and off for three years to observe the "language, taboos and rituals of this exotic community". The collider restarted in November 2009 and should gather two years of data before it shuts down for a year of scheduled upgrades in 2012. Next month, the LHC is expected to achieve record energies of 7 teraelectronvolts. The collider will reach such an extreme by accelerating two beams of protons to nearly the speed of light and then sending them in opposite directions around a 27-kilometre underground track. The beams cross each other at four spots along the ring, and it is here that the real science happens, within giant detectors surrounding each collision zone. The two biggest particle detectors, A Toroidal LHC Apparatus (ATLAS) and the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment, are the size of apartment buildings and each boasts a team of nearly 3,000 people. |

| Article |

Einstein Passes Cosmic TestGeneral relativity fits survey observations but there's still room for its rivals.  It's another victory for Einstein -- albeit not a resounding one. General relativity has been confirmed at the largest scale yet. But the galactic tests used to put the theory through its paces cannot rule out all rival theories of gravity. General relativity has been rigorously tested within the Solar System, where it explains the motion of planets with precision. But its reach between galaxies has been harder to verify and should not be taken for granted, says cosmologist Alexie Leauthaud, at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. "It's actually a tremendous extrapolation to assume that general relativity works on cosmic scales," she says. If general relativity does break down at large scales, it could help cosmologists to explain away one of their biggest headaches: dark energy. In the 1990s, astronomers were surprised to discover that the expansion of the Universe is accelerating. That runs counter to the predictions of general relativity, which suggests that gravity's grip should be slowing the expansion. To explain this, cosmologists now invoke a 'dark energy', a force that makes up almost three-quarters of the matter and energy in the Universe and pushes it apart. But the origin of dark energy remains a mystery. The accelerated expansion could be explained without dark energy, however, if general relativity is wrong and gravity weakens at cosmic scales. Several candidate 'modified gravity' theories take this line but, until now, no one has come up with a way to test them at large scales. Relative successNow, Reina Reyes at Princeton University in New Jersey and her colleagues have compared some of these models using data on the position, velocity and apparent shape of 70,000 distant galaxies mapped by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey1. The rival theories make different predictions about the degree to which light travelling to us from distant galaxies will be bent by the gravity of intermediate galaxies. This process, called 'gravitational lensing', distorts the apparent shape of the galaxies. The theories also make different predictions for both how fast galaxies grow and how they cluster together. |