Cathy Lynn Grossman

Cathy Lynn Grossman is a reporter for USA Today, where she established the coverage of religion, spirituality, and ethics for the largest paper in the United States. After graduating from the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University, she became a hard news reporter for the Miami Herald, where she worked for 17 years, covering stories from local politics to crime to international news. Following a lifelong fascination with true believers, and with the visions and values that shape human choices and actions, she studied religion and American culture on a fellowship at the University of Michigan before joining USA Today in 1989.

| Column |

Kagan, Judaism, and the Bible'Justice, justice shall you pursue'  UPDATE: 3:45 Forget Judaism, think about the fun critics might have with Elena Kagan's upper West Side upbringing, says the local Westside Independent, noting their neighborhood reputation as "a haven for cheese-eating Socialists..." And a look at the 1994 obituary for her late father, Robert Kagan, shows the kind of community activism roots that might have made her appealing to Obama. "From 1971 to 1975 he was also the chairman of COMBO, a committee representing West Side community boards, which opposed the Westway highway project. In 1968 he was the president of the United Parents Association, a citywide parents' advocacy group. He was also a trustee of the West End Synagogue." When her mother, Gloria, a teacher at Hunter College, died in 2008, the synagogue paid for a death notice honoring, "... this small but mighty, highly principled, intelligent, idealistic lady." And just in case anyone missed the religion issue, the headline on J.J. Goldberg's blog at The Jewish Daily Forward is 'How many Jews does it take to light up a high court firestorm?' UPDATE: 12:18 Reaction is coming from the predicted directions: Pro-life voices condemning Elena Kagan's nomination to the high court and liberal Democrats lauding it. But it didn't take long for religious voices to begin voicing the religious question. | ||||||||||||||||

| Column |

Nuns, Nancy Pelosi are Rock Stars to Progressive Catholics Sister Carol Keehan, lauded Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi as one of the heroes of the passage of health care reform, drew a rousing welcome today at a conference of social justice Catholics. Yesterday, Pelosi with a standing ovation and shouts of gratitude from the nuns, priest, academics and activists gathered for a "Washington Briefing" on faith and public policy. Now they added sports event-worthy cheers for the sister who spoke out for the controversial legislation. Keehan, president and CEO of Catholic Health Association and one of Time magazine's Top 100 most influential people this year, rolled her eyes when she was introduced by a long list of honors awarded by the Church and joked that she may have seen the last of those. That's because angry bishops say the legislation does not adequately block federal funding for abortion. Keehan walked through years of working for the bill, recalling how even three years back she warned others any serious proposal would be "Swift-boated" with misinformation. In the end, she said, it was not a perfect bill but it was "a superb first step," because, "the poor and the working Americans won and they so rarely win. It's wonderful." She reiterated every step she, and the sisters who joined CHA in providing critical support to the bill, followed to be certain there were no loopholes and no way to circumvent the intention to protect the unborn and prevent abortion. They worked equally hard, she said on ethical issues such as treatment for immigrants, conscience protections for health workers, care for vulnerable pregnant women, adoption support for foster parents and increased care options for the elderly. | ||||||||||||||||

| Column |

Two Speak for the 'Soul' of the Catholic ChurchBeyond the Scandal  The Catholic Church -- the one in the hearts of its people and the dusty streets of the world, not the much-troubled, abuse-rocked Vatican hierarchy -- gets some proud and profound defense this week from two directions. Columnist Nicholas Kristof, writing for the New York Times from the Sudan, finds priests and nuns living in the image of Jesus Christ that he says no person should dare scorn. And Bishop Blase Cupich of Rapid City, S.D., chairman of the Committee for Child and Youth Protection for the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops has a noteworthy essay in the upcoming Jesuit weekly magazine America. He itemizes 12 lessons the U.S. bishops learned from their scathing experience with the abuse crisis -- lessons the world church could well follow. I'll start with Kristof and two of the several people introduced in his column on finding "the great soul of the Catholic Church." He meets Michael Barton, a Catholic priest from Indianapolis, in a southern Sudan village 150 miles from any paved road where the Barton runs four schools that graduate top-scoring students. "To keep his schools alive, he persevered through civil war, imprisonment and beatings, and a smorgasbord of disease. "It's very normal to have malaria," he said. "Intestinal parasites -- that's just normal..." Anybody scorn him? Anybody think he's a self-righteous hypocrite? On the contrary, he would make a great pope." Kristof moves on to the city of Juba, where he finds Sister Cathy Arata, a nun from New Jersey now working for a " terrific Catholic project called Solidarity With Southern Sudan... | ||||||||||||||||

| Column |

Survey: 72% of Millennials 'More Spiritual than Religious'

Most young adults today don't pray, don't worship and don't read the Bible, a major survey by a Christian research firm shows.

If the trends continue, "the Millennial generation will see churches closing as quickly as GM dealerships," says Thom Rainer, president of LifeWay Christian Resources. In the group's survey of 1,200 18- to 29-year-olds, 72% say they're "really more spiritual than religious."

Among the 65% who call themselves Christian, "many are either mushy Christians or Christians in name only," Rainer says. "Most are just indifferent. The more precisely you try to measure their Christianity, the fewer you find committed to the faith."

Key findings in the phone survey, conducted in August and released today:

· 65% rarely or never pray with others, and 38% almost never pray by themselves either.

· 65% rarely or never attend worship services.

· 67% don't read the Bible or sacred texts.

Many are unsure Jesus is the only path to heaven: Half say yes, half no.

"We have dumbed down what it means to be part of the church so much that it means almost nothing, even to people who already say they are part of the church," Rainer says. The findings, which document a steady drift away from church life, dovetail with a LifeWay survey of teenagers in 2007 who drop out of church and a study in February by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, which compared the beliefs of Millennials with those of earlier generations of young people. The new survey has a margin of error of +/-2.8 percentage points. Even among those in the survey who "believe they will go to heaven because they have accepted Jesus Christ as savior": · 68% did not mention faith, religion or spirituality when asked what was "really important in life." · 50% do not attend church at least weekly. · 36% rarely or never read the Bible.

Neither are these young Christians evangelical in the original meaning of the term — eager to share the Gospel. Just 40% say this is their responsibility. | ||||||||||||||||

| Column |

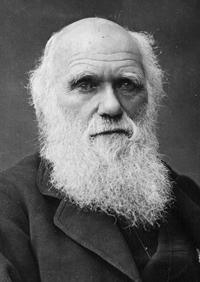

Evolution and MoralityAre we born selfish or altruistic?  Are we evolutionarily programmed to be selfish or to be cooperative? To care primarily for self, kin and survival or to sacrifice for the strength of survival of our "group?'' Can science be truly neutral in this discussion? Or are the findings of science fair game for political and social policy ammunition? Such questions -- and contesting answers -- date to Charles Darwin, August Comte (who invented the term "altruism" in 1881) to Richard Dawkins (The Selfish Gene) and on up to contemporary critics of both, says historian Thomas Dixon, a professor at the University of London and author of The Invention of Altruism. Dixon gave one of the concluding lectures at this weekend's seminars on the brain and morality at the Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Fellowships in Science & Religion. He also highlighted authors who look at cooperation through the lens of a social or political agenda and conclude, as Joan Roughgarden does in The Genial Gene, that "cooperation is every bit as natural and obvious as competition." Darwin did indeed give credence to the ruthless competition model of nature dictating organisms to "multiply, vary, let the strongest live and the weakest die." And yet, he also concluded in The Descent of Man, that love and sympathy and cooperation also exist in the natural world, like the way pelicans might provide fish for a blind pelicanin their flock? "Communities with the greatest number of sympathetic members would flourish best and produce more offspring" and, Darwin wrote, in an outburst of Victorian moral emotionalism, "virtue will be triumphant." Dawkins flips this in his work to say that the visitors of evolution are the selfish ones and that altruism must be taught. If we serve each other it's a "blessed misfiring" of genetics. | ||||||||||||||||

| Column |

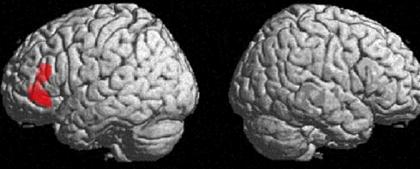

Who Killed John Lennon?Science looks at the brain and the law  Who killed John Lennon? Mark David Chapman, a psychotic, pulled the trigger, assassinating the musician/peace activist in December 1980. So who killed Lennon, the person or the brain? That's the kind of question neuroscientists, lawyers and judges are wrestling with today, says Michael Gazzaniga professor of psychology at the University of California, Santa Barbara and head of the SAGE Center for the Study of Mind. He's leading a project examining brain studies and the law -- the norms of society that are the basis of our rules. Gazzaniga "What is the brain for? It's there to make decisions," he said at a seminar on neuroscience and morality, sponsored by Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Fellowships in Science and Religion where I'm attending lectures and scooping up sources this weekend. He mused about whether brain scans be accepted in court. What's the veracity of eyewitness testimony? Do we need to revisit the 166-year-old definition of the insanity defense, given what we're learning now about free will and culpability?

After all, most people with brain diseases and conditions, from schizophrenia to people afflicted with tumors and lesions, do not commit crimes and are able to grasp and follow social rules, he says. However, the brain acquires information and makes decisions well before we are consciously forming choices. Gazzaniga says, "We're all on a little bit of taped delay between unconsciousness and awareness. But none of us believe it. We think we are in charge." | ||||||||||||||||

| Column |

Art, Ethics Evolved in the Same Way, Time, Biologist Says How do we know we evolved to be ethical when "morality doesn't leave any fossils? "

That question, from Martin Redfern of the BBC, was just one of many on the origins of ethics and morality at seminars this weekend. I've invited F&R; readers to join me here at the Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Fellowships in Science & Religion where the ideas are flying among scientists, theologians, philosophers and the reporters who cover them.

Evolutionary biologist Francisco Ayala, traced humanity's evolutionary development and linked the capacity for ethics to advanced intelligence, the development of language and the unique-to-humans concept of self-awareness. "If I know I exist, I know that I am going to die," said Ayala, professor of biology and philosophy at University of California, Irvine, who then linked this to the rise of religion. Humans are the only ones who practice ceremonial burial of the dead, he said, "We develop anxiety over our life ending so we try to look for answers beyond our life. This is likely why religion emerges in every society -- as a way to relieve this anxiety." He thinks ethics -- which can also exist apart from religion in his view -- evolved at the same time as aesthetics, the awareness of beauty. Art and aesthetics, like human altruism, require value judgments and the ability to compare. | ||||||||||||||||

| Column |

'Is God Dying?'Questions on morality, evolution and the mind  Are we evolving away from belief in God? Why did thousands of intelligent people let themselves be deceived by investment fraud king Bernie Madoff? Is morality really in decline in the West and can it be reconstructed? Such questions are in the air at a seminar on science, morality and the mind at the University of Cambridge, this weekend sponsored by the Templeton Foundation. I've participated in the Templeton-Cambridge Fellowships in Science & Religion since 2005. And for the next few days, I'd like to bring you along for a taste of the lectures and discussions. It all starts with questions. Fraser Watts, a professor of theology and science, and Director of Studies, Queens' College set the program off with a wave of his own: What can science tell us about the origin and workings of morality? How did moral capacity arise? Is it all evolutionary? What's the role of neuroscience? What goes on in the brain when we're making moral judgments? Can we use this knowledge to reconstruct morality? Michael Reiss, Professor of Science at the Institute of Education University of London, a specialist in evolutionary biology (and an ordained Anglican priest) walked us through the history of theories on altruism as an evolutionary phenomenon (like vampire bats who support each other by offering up blood if a mate didn't succeed in his own hunting) and the advantages of being good at deception (think Bernie Madoff). Even so, just knowing something has an evolutionary origin "tells you nothing about whether it is valid or useful," Reiss says. | ||||||||||||||||

| Column |

Is Dying a Criminal Act?What if you choose the day?  Montana has followed Oregon and Washington State as the third state to legalize "physician-assisted dying." Or should I use, as the Christian Science Monitor does in covering the Montana story, the term favored by opponents of these laws -- "suicide" ? The terminology is loaded, as one might expect when the topic is life and death and who decides when one is over. In Brad Knickerbocker's story this weekend, he quotes the Montana State Supreme Court, which uses the phrasing preferred by supporters of this policy. The majority justices wrote that they... : "... find nothing in the plain language of Montana statutes indicating that physician aid in dying is against public policy. In physician aid in dying, the patient -- not the physician -- commits the final death-causing act by self-administering a lethal dose of medicine." Opponents, calling it "suicide," pledged to head straight for the legislature to get new laws specifically prohibiting the practice. Meanwhile the Monitor sticks with "suicide" to describe the act of choosing when to die if you are a mentally competent adult suffering with a terminal illness. What's your call on this? Would you want this choice, however you called it, for yourself or a loved one? | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

God, Politics, Pop Culture Intertwined in '09Year in review  President Obama, a mainline Protestant who currently has no home church, dominated much of the U.S. religion news. His inaugural address called the USA "a nation of Christians and Muslims, Jews and Hindus and non-believers." In his first months, Obama lifted a Bush administration ban on federal funding for groups that offer abortion information and services abroad and expanded the policy permitting federal funds for embryonic stem cell research. Scores of Catholic bishops called it a travesty that Notre Dame, a flagship Catholic university, awarded Obama an honorary degree and invited him to deliver the commencement address in May. In his address at Cairo University in June, Obama told the Muslim world the USA is not at war with Islam. He pledged to ease the way for U.S. Muslims to make charitable donations as their faith requires. Obama used his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech in Oslo to lay out the theology of a just war and the morality of standing for the good in a world where, he said, "evil exists." U.S. Catholic bishops lobbyChurch leaders revved up their fight on "life issues" on key battle fronts — with few clear victories, particularly on gay marriage. Although it was defeated in New York and Maine, same-sex marriage was legalized in Vermont, New Hampshire and, pending a sign-off by Congress, Washington, D.C. Archbishop of Washington Donald Wuerl told the Washington city council that its approval of gay | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

More U.S. Christians Mix in 'Eastern,' New Age Beliefs Going to church this Sunday? Look around. The chances are that one in five of the people there find "spiritual energy" in mountains or trees, and one in six believe in the "evil eye," that certain people can cast curses with a look — beliefs your Christian pastor doesn't preach. In a Catholic church? Chances are that one in five members believe in reincarnation in a way never taught in catechism class — that you'll be reborn in this world again and again. Elements of Eastern faiths and New Age thinking have been widely adopted by 65% of U.S. adults, including many who call themselves Protestants and Catholics, according to a survey by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life released Wednesday. Syncretism — mashing up contradictory beliefs like Catholic rocker Madonna's devotion to a Kabbalah-light version of Jewish mysticism — appears on the rise. And, according to the survey's other major finding, devotion to one clear faith is fading. Of the 72% of Americans who attend religious services at least once a year (excluding holidays, weddings and funerals), 35% say they attend in multiple places, often hop-scotching across denominations. They are like President Obama, who currently has no home church. He has worshiped at a Baptist church, an Episcopal one, and the non-denominational chapel at Camp David. "Mixing and matching practices and beliefs is as much the norm as it is the exception," Pew's Alan Cooperman says. "Are they grazing, sampling, just curious? We really don't know." Even so, says Pew researcher Greg Smith, "these findings all point toward a spiritual and religious openness — not necessarily a lack of seriousness." | ||||||||||||||||

| Column |

The 'Scandal" of Charles Darwin, in Literature, Society The findings were unnerving: We are not the favored creation of God. Species that have vanished forever are greater in number and possibly more important that those that live. Change may not be an uninterrupted progress toward perfection. Small wonder that Charles Darwin was slow and frightened to finally publish his great work, The Origin of Species, and face "scandal" over his theories of "kinship, extinction and the great family," says Dame Gillian Beer, emeritus professor of English literature at Cambridge and author of Darwin's Plots: Evolutionary Narrative in Darwin, George Eliot, and Nineteenth Century Fiction. Beer set Darwin's extraordinary and revolutionary work in a social and literary context in today's lecture at the Templeton-Cambridge program I'm attending this week in England. She talked about how a man who felt a "backbone shiver" of pleasure with music and poetry when he was young lost this as an older man, troubled by the antipathy to his ideas. He still found pleasure of novels, particularly those with a happy ending. This fits a man obsessed with the questions of the novels of his time, all about descent, inheritance and family. "He thinks about where is the human. What is the scale of the human?" Beer says. And "he was going to show that human beings had a very brief part of the history of the world." Darwin would also redefine the "great family" so that "great" no longer meant aristocratic, educated, landed and wealthy but "great" as in large and wide and old, part of organisms past and present, "not a very privileged place." | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

Most Religious Groups in USA Have Lost Ground, Survey Finds "More than ever before, people are just making up their own stories of who they are. They say, 'I'm everything. I'm nothing. I believe in myself,' " says Barry Kosmin, survey co-author. Among the key findings in the 2008 survey:

| ||||||||||||||||

| Column |

Does the free market corrode morality? Tough question, right? The Templeton Foundation, best known for massively funding research and programming in the realms of science and religion, took this on as one of its topics in a series of publications and forums on the "Big Questions" in modern times. Three leading economic and philosophical intellectuals held a seminar today in London (I watched on webcast) to address, "Does the free market corrode moral character?"' Gary Rosen of the Templeton Foundation began by reminding the audience that the foundation founder, the late Sir John Templeton, once said, "Through risk and challenge we grow both in worldly wisdom and spiritual strength." Unfortunately, I'm not so far grown in wisdom yet. Much of the discussion went over my head. Even so, it was clear that there are rousing arguments among the global intelligentsia over markets and morality. "All humanly acceptable economic systems are morally corrosive to some extent," said John Gray, an emeritus professor at the London School of Economics and author of False Dawn: The Delusions of Global Capitalism. Gray argued that the modern version of the American free market died "from hubris and greed that promoted snatching wealth from pyramids of debt." Jagdish Bhagwati, a professor of economics and law at Columbia University, added "ignorance" to black marks on the free market. He said the new financial instruments, such as derivatives packaging "toxic" mortgages, went beyond the knowledge of the central bankers. They took the brakes off regulation without ever understanding that this might become "a dagger at our throat," he said. | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

Dealing with Evil: Candidates DisagreeWhere does evil dwell: in the devil or in mankind?  God either causes or allows “major tragedies to occur as a warning to sinners,” say 20% of U.S. adults. While 43% say most evil is caused by the devil, 47% disagree–a statistical tie. But most (68%) would not say human nature is basically evil. So where does evil dwell–in the devil or in mankind? The Baylor survey allows for overlapping views; it finds 36% strongly agree with both statements. Presence of evil

Source: The Baylor Religion Survey, the Institute for Studies of Religion, Baylor University. Based on a survey of 1,700 U.S. adults conducted in fall 2007 with a margine of error of ±4 percentage points. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding. “Those who believe God causes or allows bad things to happen did not speak in terms of tragedies being God's fault,” says Baylor sociologist Christopher Bader. Bader says people told him that “tragedies are our fault. We have sinned as a nation and God has stood aside and allowed terrible things to happen.” | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

The Face of Islam in America HARTFORD, Conn. — Ingrid Mattson knows the media drill well. She has done the "We condemn … (fill in the terrorism incident)" speeches — as if, she says, that's all anyone needs to hear from the president of the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA). She has done the profiles of her as first woman/first convert/first North American-born head of the continent's largest Muslim group. She has done the talk shows retelling how 20 years ago, she left the Catholicism of her Canadian childhood and her college focus on philosophy and fine arts to find her spiritual home in Islam. "It's time now to move the focus back off me and back on the issues," says Mattson, a professor at Hartford Seminary, where she directs the first U.S.-accredited Muslim chaplaincy program at the Macdonald Center. Mattson begins the second half of her two-year term at the society's Labor Day weekend national conference outside Chicago. The annual event draws 40,000 Muslims of every sect, culture, age, race and ethnicity for scores of sessions on faith, family and society and a massive multicultural bazaar. But two weeks before the conference, sitting with two women in her tiny, book-stuffed office, Mattson has a moment to kick off her shoes. She sheds the long brown jacket stifling her tailored blue blouse, leans back and talks about her vision of American Muslim life | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

Americans Get an “F” in Religion Sometimes dumb sounds cute: Sixty percent of Americans can’t name five of the Ten Commandments, and 50% of high school seniors think Sodom and Gomorrah were married. Stephen Prothero, chairman of the religion department at Boston University, isn’t laughing. Americans’ deep ignorance of world religions—their own, their neighbors’ or the combatants in Iraq, Darfur or Kashmir—is dangerous, he says. His new book, Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know—and Doesn’t, argues that everyone needs to grasp Bible basics, as well as the core beliefs, stories, symbols and heroes of other faiths. Belief is not his business, says Prothero, who grew up Episcopalian and now says he’s a spiritually “confused Christian.” He says his argument is for empowered citizenship. “More and more of our national and international questions are religiously inflected,” he says, citing President Bush’s speeches laden with biblical references and the furor when the first Muslim member of Congress chose to be sworn in with his right hand on Thomas Jefferson’s Quran. “If you think Sunni and Shia are the same because they’re both Muslim, and you’ve been told Islam is about peace, you won’t understand what’s happening in Iraq. If you get into an argument about gay rights or capital punishment and someone claims to quote | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

Long-Lost Gospel of Judas Recasts 'Traitor' (article co-written by Dan Vergano) Lost for centuries and bound for controversy, the so-called gospel of Judas was unveiled by scholars Thursday. With a plot twist worthy of The Da Vinci Code, the gospel — 13 papyrus sheets bound in leather and found in a cave in Egypt — purports to relate the last days of Jesus' life, from the viewpoint of Judas, one of Jesus' first followers. Christians teach that Judas betrayed Jesus for 30 pieces of silver, but in this gospel, he is the hero, Jesus' most senior and trusted disciple and the only one who knows Jesus' true identity as the son of God. "We're confident this is genuine ancient Christian literature," said religious scholar Bart Ehrman of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. He and others on the translation team spoke at a National Geographic Society briefing, where they released a translation. The manuscript claims that Jesus revealed "secret knowledge" to Judas and instructed him to turn Jesus over to Roman authorities, said Coptic studies scholar Stephen Emmel of Germany's University of Munster, one of the restoration team members. In the gospel text, Judas is given private instruction by Jesus and is granted a vision of the divine that is denied to other disciples, who do not know that Jesus has requested his own betrayal. Rather than acting out of greed or malice, Judas is following orders when he leads soldiers to Jesus, the gospel says. Other theologians, biblical scholars and pastors say this contrary text is not truly "good news" (the meaning of "gospel") and will make no difference to believers as Easter approaches. The Bible, they say, is a closed book, nearly universally accepted as the official church teachings since the fourth century. "Just because you can date a document to early Christian times doesn't make it theologically true," said Pastor Rod Loy of the First Assembly of God in North Little Rock "Do you decide everything you read on the Internet is true because it was written on April 6, 2006? Fiction has been around for as long as man." Found by a farmerRadioactive-carbon-dating tests and experts in ancient languages establish that the document was written between A.D. 300 and 400, the team said. Written in Coptic, an old Egyptian language, the gospel was unearthed by a farmer in a "tomb-like box" in 1978, said Terry Garcia of the National Geographic Society. It is part of a codex, or collection of devotional texts, found in a cave near El Minya, Egypt. The farmer sold the codex to an antiquities dealer in Cairo, without alerting Egyptian antiquities officials. In a secret showing in 1983, the antiquities dealer, unaware of the content of the codex, offered the gospel for sale to Emmel and another scholar in a Geneva, Switzerland hotel room. Given a hurried half-hour to examine the codex, Emmel first suspected the papyrus sheets discussed Judas, he said, based on a hasty glimpse of the text, which was littered with references to the disciple in Coptic. But the asking price was too exorbitant, as high as $3 million, Garcia said.

For the next 16 years, the document moldered in a Hicksville, N.Y., bank safe-deposit box, deteriorating until Zurich-based antiquities dealer Frieda Nussberger-Tchacos purchased it in 2000, alarmed at its fragmentation, Garcia said. National Geographic said it did not know the purchase price. In 2001, the codex was acquired by the Maecenas Foundation for Ancient Art in Switzerland, Garcia said. The foundation invited National Geographic to help with the restoration in 2004 and also reached an agreement with the Egyptian government to return it after its restoration. Restoration of the thousands of papyrus fragments has made 80% of the gospel legible. The National Geographic Society learned of the find 2½ years ago, Garcia said. The society recruited the scholarly restoration team and got a $1 million grant from the Waitt Foundation for Historical Studies. The gospel "is an intriguing alternative view of the relationship between Jesus and Judas," Emmel said. It also has Jesus relating a new creation myth and account of humankind's origins to Judas, which suggest God didn't create the world, contrary to conventional Christian belief. The key passage has Jesus telling Judas "'you will exceed all of them. For you will sacrifice the man that clothes me,'" Emmel said. The | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

South Korean Scandal Brings Worries in Stem Cell ProjectsEmbryonic stem cell researchers are worried about the future of international cooperation in their field after a prominent scientist's surprise resignation from a fledgling stem-cell-sharing effort. On Thanksgiving, South Korean scientist Woo-suk Hwang of Seoul National University resigned as head of the World Stem Cell Hub, a nascent international embryonic stem cell research effort he started. In 2004, Hwang's team was the first to clone human embryonic stem cells, master cells from which specific kinds of tissue arise. Since then, Hwang's team has become the world's leader in stem cell research. This year, it unveiled 11 more cloned stem cell lines, and it cloned a dog. But a team member, the University of Pittsburgh's Gerald Schatten, resigned this month. He warned of ethical breaches involving junior lab members inappropriately donating eggs for research. Donor eggs are combined with skin cells in the cloning process. Hwang's 2004 paper said all eggs had been freely given by anonymous donors. But he acknowledged that a team doctor paid 20 women about $1,400 each to donate eggs. Hwang also confirmed Schatten's charges. Hwang acknowledged that he did not disclose these breaches upon learning of them. "No question that people are taking a step back from interacting with the Hub," says Leonard Zon, former president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research. "It remains for Dr. Hwang's colleagues to prove the future of the Hub can be maintained." The organization will outline new ethics guidelines this week. Paul Root Wolpe of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania points out that Hwang did not resign because he used eggs from his researchers but because he lied about it and brought shame "in a country where public shame is so powerful." He is not the only one to note that Hwang's findings have not been compromised. "While ethical issues about (egg) donation should be debated and the process regulated, the scientific conclusions of Dr. Hwang's research remain intact," Schatten said in a statement. The South Korean government says it will still pay for Hwang's work, and thousands of women have since offered their eggs, according to news reports. "Korean bioscientists have opened a new era with cutting-edge technology, but I don't think there is any bioethics relevant to that at this moment here," says theologian Heup Young Kim of South Korea's Kangnam University. "We have our different social and cultural context, so we have to formulate our own bioethics." One irony of Hwang's resignation is that South Korea's egg donation standards, and those of Hwang's lab, are now stricter than U.S. standards, says bioethicist Insoo Hyun of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. The lab requires consent forms and psychological evaluations for donors. And earlier this year, South Korea outlawed paying for eggs, which is legal in the USA. Stem cell researchers hope to create replacement tissues to treat diseases such as diabetes and Parkinson's. Opponents assail the destruction of embryos involved in gathering the cells. President Bush has restricted research money. "I would hate to see the United States get on an ethics high horse as if we are moral and other countries such as Korea are not," says the Rev. Ronald Cole-Turner of Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. "Which society is the more ethical?" he asks. "The one that at least has a standard or the one that can't find a reasonable degree of compromise to create a standard?" | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

The Whole World, from Whose Hands? The battle between secular defenders of evolution and those who believe in a divine Creator is more than a century old, yet there’s no lessening in its emotional and intellectual intensity. The latest wrinkle is intelligent design, a boundary-crossing belief that is the focus of a federal court trial on whether it should be taught in schools. A new USA TODAY/CNN/Gallup Poll sheds light on where Americans stand (53% of respondents say the Bible had it right). And USA TODAY religion writer Cathy Lynn Grossman and science reporter Dan Vergano look at the opposing sides to learn why each believes it cannot be wrong. Creationists: “If you don’t have God at the beginning…”Cut to the chase: It’s about God. In the war of worldviews, He cannot lose. As famed orator William Jennings Bryan wrote in 1925, “God may be a matter of indifference to the evolutionists, and a life beyond may have no charm for them, but the mass of mankind will continue to worship their creator and continue to find comfort in the promise of their Savior that he has gone to prepare a place for them.” Marvin Olasky puts it more bluntly: “If you don’t have God at the beginning, you don’t have God at the end and you don’t have God in | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

50 Years of ChangeIn the past half-century, death has been transformed by scientific, technological and social changes. Today, about 80% of Americans die in a health care facility. Some milestones: 1950sRespiratory support, particularly by ventilators, gains widespread use to sustain polio patients. 1960s1963: Kidney dialysis invented in Seattle. 1965: Medicare increases access to medical care for millions of Americans, raising new ethical questions: How much to spend? How far to go? 1966: National Academy of Sciences recommends training physicians in the new lifesaving technique of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. 1965-68: National Institutes of Health revolutionizes research and treatment ethics, calling for informed consent for tests, surgeries and procedures. 1967: The first successful heart transplant prompts Harvard anesthesiologist Henry Beecher to seek a new criteria for death to allow transplants of vital organs while the heart is still beating. 1968: Harvard Ad Hoc Committee to Examine the Definition of Death adds brain-death criteria — irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain — to the traditional heart-death definition. | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

Where the Faiths StandOregon's law allowing a dying person to seek a doctor's prescription for a lethal dose of medication breaks with traditional religious doctrines:

Catholic:

"We are encouraged, if our end is to be loving, to examine how can we do that best. I don't love someone best by saying, 'There are no possibilities for you, no hope or meaning...' Who am I to say that?"

—

| ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

Quotes: Death and Dying

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

| ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

Defining the Language of Life, DeathThe vocabulary of death and dying is elusive. Words raise questions about end-of-life decisions not just for patients and families but for clergy, doctors, ethicists. etc. USA TODAY asked experts to comment. The vocabulary of death and dying is elusive. Words raise questions about end-of-life decisions not just for patients and families but also for clergy, doctors, legal experts, ethicists and academicians. Advance directivesThe two best-known advance directives — an umbrella term for written or verbal instructions for medical care if someone is incapacitated and cannot make decisions — are the health care proxy, also called power of attorney, and the living will. A living will can be a general indication of someone's wishes or a specific listing of types of care, such as a feeding tube, the patient might wish to reject under certain circumstances. The proxy designates someone who knows the patient's wishes as the surrogate decision-maker. But even though hospitals are required to ask patients whether they have these documents, health care researchers have found that living wills frequently fail because they are too often vague, confusing, expensive and not always enforced. A report last week by the President's Council on Bioethics called living wills "of limited value." AutonomyBioethics experts who operate from primarily secular principles say a person's right to determine his or her own course should be the most important factor in making medical decisions. "In our pluralistic society, we go by the patient's values, religious or secular, and not necessarily our own," says Timothy Quill, professor of medicine, psychiatry and medical humanities at the University of Rochester | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

When Life's Flame Goes OutAmericans talk endlessly about death. We want a "good death," a "natural death," a "death with dignity," researchers say. We'd like to say all farewells, repent all sins — or accept our karmic consequences — and then blink out like a candle. We just can't agree on what that looks like, how it happens, even the very definition of "death." Our society is splintered on when — or whether — to begin or end a bewildering array of life-support technologies that didn't exist 50 years ago. When the end is near, must we leave the timing to God or nature? Today the U.S. Supreme Court hears a challenge to the Oregon law that allows doctors to prescribe a lethal overdose for a dying patient. Advocates for the law call it "physician-assisted dying." Opponents call it suicide — or murder. The Bush administration will argue that Oregon's Death with Dignity Act violates federal drug laws; the case of Gonzales v. Oregon probably will turn on the fine point of state vs. federal authority. But public debate has not been so confined. Opinion polls since 1973 suggest that most Americans have supported allowing someone with "an incurable disease" to end his or her life "by some painless means." In a USA TODAY/CNN/Gallup Poll in 2004, 69% supported that view. But that could apply to people who refuse or stop medical treatment they consider futile. () When Americans were asked in a USA TODAY/CNN/Gallup Poll in September whether a doctor should be allowed to prescribe an overdose to help someone "end his or her life," 54% said yes. When the question used the words "help the patient commit suicide," 46% said yes. | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

When the Questions Get Difficult, Here's Where to TurnHigh-profile voices from five bioethics centers across the country comment on the field of bioethics.  Daniel Callahan

Daniel Callahan

The Hastings Center, Garrison, N.Y., calls itself the "oldest independent, non-partisan bioethics research institute." Director Daniel Callahan, who founded the multi-disciplinary center in 1969, says it is secular, but raises questions from many perspectives, including religion. Some Hastings fellows support embryonic stem cell research; Callahan, an atheist, opposes it. The debate "is typically cast as balancing the destruction of embryos vs. the lives that might be saved" by using them. But he asks "Do we have a moral obligation to come up with these cures? What are the values and boundaries of research, its limits?"  Tom Beauchamp

Tom Beauchamp

Kennedy Institute of Ethics at Georgetown University, which was founded in 1971, calls itself the "world's oldest and most comprehensive academic bioethics center." Many of the top bioethicists trained here with professors such as Tom Beauchamp, who is co-author of Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Traditional Catholics blast Beauchamp for serving on the board of an organization that promoted an Oregon law allowing physicians to prescribe a lethal drug dose for terminally ill patients. But he says moral principles such as autonomy are not based in any one theology: "What secular ethics is fundamentally about in a secular society is what we can all agree on." The University of Pennsylvania Center for Bioethics, founded by former Hastings fellow Arthur Caplan, is multidisciplinary; sociologist Paul Root Wolpe, NASA's first bioethics chief, is a senior fellow, as is his father, Rabbi Gerald Wolpe. Paul Wolpe often asks questions raised by medical advances: "Did morality change since 1970 just because we can keep someone going who would have died? Just because we can is not a moral argument."  C. Ben Mitchell

C. Ben Mitchell

The Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity, which is affiliated with Trinity International University in Deerfield, Ill., takes a conservative Christian view, including commitment to belief in the bodily resurrection of the dead. | ||||||||||||||||

| Article |

Bioethics 'Expertise' Comes from All CornersAny given Sunday morning, a bioethicist somewhere in America suits up for a TV appearance on the hot issue of the day or stands by a hospital bed to consult on a wrenching dilemma. Should doctors prolong the life of a baby born without a brain? Should they be allowed to help the terminally ill kill themselves by prescribing a lethal drug dose? Should there be limits on embryonic stem cell research? But who are these people opining on what we should do? "Anyone who wants to," says Arthur Derse, chairman of Veterans' Health Administration's National Ethics Committee. He's president of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, which draws most of its 1,600 members from medical schools and academics in ethics and philosophy. Lawyers, theologians, clergy members, sociologists and others staff scores of bioethics centers and work in the pharmaceutical industry as well. There are no standards or certification procedures, says Derse, an emergency medicine physician. And rarely are bioethicists questioned about the basis for their views or who pays for their work. It's hard for the average person to sort out the political activists with an agenda or ethicists with a vested interest, such as those employed, directly or indirectly, by drug companies seeking an ethical halo for their products. |