Edwin Cartlidge

Edwin Cartlidge, formerly the news editor of the British publication Physics World, is a freelance journalist based in Rome. He continues as a regular contributor to Physics World, writing about physics and related matters as well as science and religion for both its print magazine and website. His work also appears in Science, the Economist, and New Scientist.

| Article |

When Is It Ramadan?An Arab Astronomer Has Answers.  This week will see the start of the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, a time when hundreds of millions of Muslims around the globe devote themselves to fasting and prayer. But to Algerian scientist Nidhal Guessoum, a Sunni Muslim, it's also a time of chaos—and "an embarrassment" to Islam. Tradition dictates that Ramadan, like other holy months in the Islamic calendar, begins the day after the thin crescent of the new moon is first seen with the naked eye. Because visibility is very dependent on local atmospheric conditions, religious officials in different countries—relying on eye-witness observations from volunteers—often disagree on the exact moment, sometimes by as much as 3 or 4 days. It's a recipe for international confusion. Guessoum, an astrophysicist at the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates, is one of the most high-profile advocates of a scientific approach to the problem that would end the confusion. Its adoption would not only help Muslims plan their lives—"I need to know whether I can hold a meeting on August 30," Guessoum says—but also be a sign that Muslim countries, once at the forefront of science, are again "able to integrate science into social and cultural life," he says. Guessoum, the vice president of an international organization known as the Islamic Crescents' Observation Project (ICOP), believes science can help solve other practical problems in the Muslim faith. In frequent TV appearances, public lectures, blog posts, and books, he has explained how astronomical techniques can help determine prayer times in countries far from the equator or establish the direction of Mecca. His attempts to apply science to Islamic rituals has earned him respect, but they have also ruffled the feathers of religious conservatives. So has his support for biological evolution and his rejection of claims that the Koran anticipated much of modern science. He can make people without much scientific knowledge "uneasy," says Zulfiqar Ali Shah, an influential U.S. cleric who supports his ideas about the Islamic calendar. When dealing with religious scholars, Guessoum "is very respectful but forceful," Ali Shah adds. Guessoum, 50, obtained a physics degree in Algeria in 1982. He earned a Ph.D. in theoretical astrophysics at the University of California, San Diego, after which he spent 2 years at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, working on gamma ray astrophysics, which is still the focus of his research. A "moral and financial duty" to pay back for his education made him return to Algeria in 1990. There, ordinary people and religious officials often asked him to explain the science of crescent sighting, a topic that astronomer Bradley Schaefer, now at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, had got him interested in. He published a book on the topic in Arabic in 1997. |

| Review |

Morality Without TranscendenceCan science determine human values?  When anthropologists visited the island of Dobu in Papua New Guinea in the 1930s they found a society radically different from those in the West. The Dobu appeared to center their lives around black magic, casting spells on their neighbors in order to weaken and possibly kill them, and then steal their crops. This fixation with magic bred extreme poverty, cruelty and suspicion, with mistrust exacerbated by the belief that spells were most effective when used against the people known most intimately. For Sam Harris, philosopher, neuroscientist and author of the best-selling The End of Faith and Letter to a Christian Nation, the Dobu tribe is an extreme example of a society whose moral values are wrong. In his new book, The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values, Harris sets out why he believes values are not, as is widely held, subjective and culture-dependent. Instead, he says, values are a certain kind of fact — facts about the well-being of conscious creatures — and that they can therefore, at least in principle, be objectively evaluated. The "moral landscape" of the title is the concept that certain moral systems will produce "peaks" of human well-being while others, such as that of the Dobu, will lead to societies characterized by a slough of suffering. Harris maintains that it is possible to determine objectively that the former are better than the latter. Harris is not the first person to advocate an objective basis for morality. The biologist E. O. Wilson, for example, has previously explained how he believes moral principles can be demonstrated as arising objectively from human biological and cultural evolution. But in arguing that there is an objective basis to morality, Harris puts himself at odds with a principle put forward by the 18th century philosopher David Hume and regarded as inviolable by many philosophers and scientists today: the idea that statements about how things ought to be cannot be derived from statements about what is true. In other words, it is impossible to derive values from facts. Harris dismisses both this reasoning and the objection that there are no grounds for favoring his moral framework over any other. He takes it to be essentially self-evident that morality is about well-being, arguing that some practices, such as forcing women to dress head to toe in a burqa, are bound to reduce well-being. In Harris’s view, it is not right to treat all cultural practices as being equally valid and maintains that multiculturalism and moral relativism are wrong. |

| Article |

Something Rather Than NothingThe scientists who find space for religion  Not all scientists share Stephen Hawking’s view that modern physics makes the Creator redundant, writes Edwin Cartlidge. Among these is John Polkinghorne of Cambridge University, who is well known for his studies on the relationship between science and religion, having worked as a particle physicist for 25 years before becoming ordained in the Church of England. Polkinghorne says his religious belief does not spring from one "knockdown argument" for the existence of God but instead derives from a number of different sources. Among these are personal experience, including worship and reflecting on the decisions he has taken in life. But he also draws faith from the very fact that the universe is intelligible and describable in terms of mathematics, and that the laws of nature appear to be finely tuned to support life. This observation he believes is more satisfactorily explained by the existence of God than the possibility of countless parallel universes – among which one is bound to be suited to life – or simply the brute fact of existence. Polkinghorne finds much common ground with nuclear physicist and theologian Ian Barbour of Carleton College in the US, including the belief that both science and religion seek to explain an objective reality that cannot be understood in a straightforward way. But Polkinghorne has a more traditional view of Christ than Barbour, believing that Christ was both fully human and fully divine, that he was born of a virgin and that he was resurrected. Indeed, Polkinghorne believes there is both good historical evidence and strong theological motivation for the Resurrection. Barbour, however, disputes both the reality of the empty tomb and the virgin birth. |

| Column |

Fine-Tuning the UniversePhysicists and theologians gathered in Oxford last week to discuss the complex relationship between their two disciplines, and to pay tribute to physicist and priest the Revd Dr John Polkinghorne. But in doing so, some also posed challenges to his thinking.  'Epistemology models ontology" is one of the Revd Dr John Polkinghorne’s favourite phrases. It means, roughly speaking, that what we know is a reliable guide to what is actually out there in the world. In fact, he used to say it so often that his wife gave him a T-shirt with the words emblazoned upon it. It was in the same spirit that staff from the Ian Ramsey Centre for Science and Religion at the University of Oxford tried unsuccessfully to find a T-shirt with another of Dr Polkinghorne’s trademark expressions, "bottom-up thinker", ahead of a four-day conference being held at the centre last week to mark Dr Polkinghorne’s eightieth birthday later this year. Bottom-up thinking is central to Dr Polkinghorne’s view of reality. He carried out research in particle physics for nearly 25 years before quitting academia and training for the Anglican priesthood. Then, after serving as a parish priest for several years, he returned to the academic fold to become president of Queens’ College, Cambridge, and to investigate the interplay between science and religion. He says that his work as a scientist showed him the importance of experience as a guide to what is true, rather than assuming that the world will conform to certain preconceived abstract principles. He maintains that the core of modern physics – quantum mechanics – with its strange, probabilistic conception of nature, would never have been dreamed up from scratch but instead came about because experimental results demanded it. For Dr Polkinghorne, this way of thinking applies equally to theology. He argues that it is mistaken to try to prove that God exists using pure logic since, as he puts it, "clear and certain ideas often turn out to be neither clear nor certain". Indeed, he says, there is no "knockdown argument" for the existence of God. Rather, his religious belief derives from a number of different sources. These include his experience of worship and a reflection on the decisions he has taken in his life, as well as his belief in the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. In addition, Dr Polkinghorne draws on a couple of general observations he can make as a scientist. One of these is simply the very intelligibility of the universe, the fact that it is possible to make theories about the way the world works and to use mathematics as the language of those theories, an ability which, he claims, could not have come about through mere evolutionary necessity. |

| Column |

Life, but Not as We Know ItLast week researchers in America announced that they had created a new kind of artificial life. Is this venture into the unknown fraught with danger, or a useful step forward with beneficial consequences for us all?  To many people, the idea of a living being suggests something that is more than just atoms but also a thing formed with a divine spark or a vital essence. But now what we mean by life itself will have to change following the creation by Craig Venter of the world’s first "synthetic cell". It is, as Venter puts it: "The first self-replicating species that we’ve had on the planet whose parent is a computer." Venter, the biologist who mapped the human genome in 2001, has designed a bacterial genome on a computer, building the genome from scratch using chemicals, inserting the genome into a hollowed-out cell and then watching that cell reproduce. But have Venter and his colleagues really synthesised new life in the laboratory? And if so, what does this achievement tell us about life itself, and what benefits – and ethical dangers – might it bring to mankind? The cell created by Venter and colleagues at the J. Craig Venter Institute in Maryland is the result of a research programme that has lasted more than a decade and cost around US$40m. As reported in the journal Science, the cell was made in a multi-stage process that included the sequencing, or mapping out, of the one million chemical bases of the bacterium Mycoplasma mycoides. After digitising this code on a computer and tweaking it to eliminate a few unwanted genes and add in "watermarks" that would identify the genome as synthetic, the researchers split the genome into about 1,000 segments of equal length. The job of actually building these segments fell to an outside synthesis company. Then, with the segments in hand, Venter’s group stitched them together using yeast and inserted the complete synthesised genome into the cell of a different, but related, bacterium. Finally, with the genome of the host bacterium destroyed as a result of the transfer, the cell reproduced to generate multiple copies of Mycoplasma mycoides. The breakthrough has created intense media interest worldwide and has clearly impressed many scientists and other academics, none more so than Arthur Caplan, a professor of bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States. Describing the work as "monumental", he argues it "brings to an end a 3,000-year-old debate about the nature of life" – whether living things are fundamentally different to non-living things in that they require some kind of a vital spark to animate them. For Caplan, the fact that Venter and co-workers created a living, reproducing cell using a genome that was built up from chemicals and not from other living matter means that the debate has now been settled. "Vitalism has been put to bed," he says. |

| Column |

Of Money and MoralitySome of the world's leading economists and social scientists gathered at the Vatican to discuss the causes and effects of the global financial crisis, and to debate what can be done to put economics on a sound ethical footing.  In June last year, Pope Benedict XVI issued his encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, or "Charity in Truth", in which he examined the central role of charity in the Catholic Church’s social doctrine and how this must be guided by the pursuit of truth. Truth, he said, "preserves and expresses charity’s power to liberate in the ever-changing events of history", adding that without truth "there is no social conscience and responsibility, and social action ends up serving private interests and the logic of power". In particular, Benedict focused on justice and the common good – concepts, he said, that are particularly important to the healthy functioning of our increasingly globalised society. Analysing these themes in the light of the world’s ongoing financial and economic crisis, the Church’s Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences held a plenary meeting from 30 April to 4 May entitled, "Crisis in a global economy: replanning the journey". The academy, set up in 1994, is designed to "promote the study and progress" of the social sciences and thereby support the Church in the development of its social doctrine. It is made up of several dozen of the world’s leading social scientists, who, on this occasion, were joined by other experts in economics and finance as they gathered at the academy’s sixteenth- century headquarters in the Vatican gardens to examine the political, cultural and ethical, as well as economic, dimensions of the crisis. Providing an insight into the causes of the crisis and discussing the potential for further upheaval was Mario Draghi, governor of the Bank of Italy and chairman of the G20’s Financial Stability Board. According to Draghi, an "ideological bias" lay behind the crisis, with financiers and regulators wrongly believing that the market, left to its own devices, would weed out bad debt. He told delegates that the global financial markets had been "stabilised" but that the underlying problems had not gone away. In fact, said Draghi, the banking system is now in a worse position than it was before the crisis because there are still plenty of banks that are "too big to fail" but which now know, given the enormous bail-outs provided by the United States, British and other governments, that "they cannot fail". |

| Article |

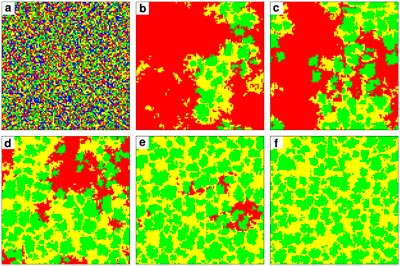

Physicists Study How Moral Behaviour Evolved A statistical-physics-based model may shed light on the age-old question "how can morality take root in a world where everyone is out for themselves?" Computer simulations by an international team of scientists suggest that the answer lies in how people interact with their closest neighbours rather than with the population as a whole. Led by Dirk Helbing of ETH Zurich in Switzerland, the study also suggests that under certain conditions, dishonest behaviour of some individuals can actually improve the social fabric. Public goods such as environmental resources or social benefits are often depleted because self-interested individuals ignore the common good. Co-operative behaviour can be enforced via punishment but ultimately co-operators who punish will lose out to co-operators who don't punish because punishing requires time and effort. These non-punishing co-operators then lose out to the non co-operators, or free riders. With free riders dominant the resource is depleted, to the detriment of everyone – a scenario known as "tragedy of the commons". How, then, does co-operation arise? Some researchers have proposed that co-operators who punish could survive through "indirect reciprocity", the idea that working for the common good will enhance a person's reputation and ensure that they benefit in the future. Helbing's group, however, has shown that this is not needed for co-operation to flourish. Emergent phenomenaThey came to this conclusion by focusing on how individuals behave with their nearest neighbours, rather than a wider group that is representative of the entire population. Like nearest-neighbour models of magnetism – which are often more realistic than mean-field approximations – they say that this approach captures "emergent" phenomena that would otherwise be lost. |

| Article |

The Man with Clues to RealityThis year's Templeton Prize winner is a champion of both science and religion. Spanish-born Francisco Ayala roundly dismisses creationism and intelligent design and says evolution can help religious believers understand evil.  By his own admission, Francisco J. Ayala has had "a very chequered career". After graduating in physics in his native Spain, he studied theology and became a priest, before moving to the United States, where he has dedicated the rest of his career to evolutionary genetics and molecular biology. This varied intellectual path has, however, put the 76-year-old Ayala in a good position to explore the relationship between science and religion, which he believes provide complementary perspectives on our existence and are not in conflict with one another. It has also landed him this year’s Templeton Prize, an award given by the Templeton Foundation in the United States to an individual "who has made an exceptional contribution to affirming life’s spiritual dimension, whether through insight, discovery or practical works", and which is accompanied by a cheque for £1 million. Born in Madrid in 1934, Ayala grew up under the dictatorship of General Franco. He was ordained as a Dominican priest in Salamanca in 1960 but realised that his true vocation lay in science. He remained a priest for about four years, agreeing with his superiors that he would go off and study genetics as long as he continued to obey his vows during this time. He travelled to New York, where he studied under celebrated biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky at Columbia University and then moved west to California in the early 1970s. Among his many contributions to genetics and evolutionary biology, Ayala has pioneered ways of using variations in DNA sequences to reconstruct evolutionary history. He has also carried out much research on malaria and other tropical diseases, for example recently discovering that malaria was probably passed from chimpanzees to humans just around 5,000 years ago and that chimpanzees may serve as reservoirs for malarial parasites, leaving humans vulnerable to the disease even if a vaccine is developed. |

| Article |

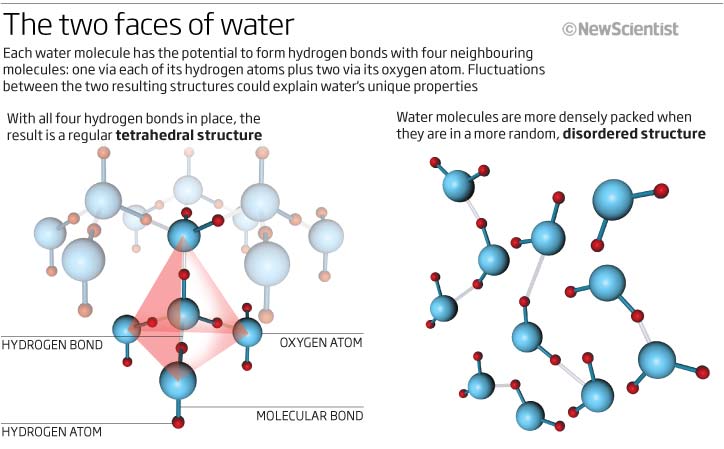

The Strangest LiquidWhy water is so weird  We are confronted by many mysteries, from the nature of dark matter and the origin of the universe to the quest for a theory of everything. These are all puzzles on the grand scale, but you can observe another enduring mystery of the physical world - equally perplexing, if not quite so grand - from the comfort of your kitchen. Simply fill a tall glass with chilled water, throw in an ice cube and leave it to stand. The fact that the ice cube floats is the first oddity. And the mystery deepens if you take a thermometer and measure the temperature of the water at various depths. At the top, near the ice cube, you'll find it to be around 0 °C, but at the bottom it should be about 4 °C. That's because water is denser at 4°C than it is at any other temperature - another strange trait that sets it apart from other liquids. Water's odd properties don't stop there (see "Water's mysteries"), and some are vital to life. Because ice is less dense than water, and water is less dense at its freezing point than when it is slightly warmer, it freezes from the top down rather than the bottom up. So even during the ice ages, life continued to thrive on lake floors and in the deep ocean. Water also has an extraordinary capacity to mop up heat, and this helps smooth out climatic changes that could otherwise devastate ecosystems. Yet despite water's overwhelming importance to life, no single theory had been able to satisfactorily explain its mysterious properties - until now. If we can believe physicists Anders Nilsson at Stanford University, California, and Lars Pettersson of Stockholm University, Sweden, and their colleagues, we could at last be getting to the bottom of many of these anomalies. Their controversial ideas expand on a theory proposed more than a century ago by Wilhelm Roentgen, the discoverer of X-rays, who claimed that the molecules in liquid water pack together not in just one way, as today's textbooks would have it, but in two fundamentally different ways. |

| Article |

Law and the End of the WorldEdwin Cartlidge examines the case of a US lawyer who believes that the courts must step in if required to halt experiments like the Large Hadron Collider.  Before the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) was switched on at CERN in September 2008, stories abounded that the machine might destroy the planet. The fear was that the €6.3bn LHC, which will collide protons together at energies of up to 14 TeV, would be powerful enough to create mini black holes that could consume the Earth – or that it might produce hypothetical "strangelet" particles that could convert the planet into a lump of ultra-dense "strange" matter. These stories certainly left their mark, with people telephoning the Geneva lab in tears imploring researchers not to switch on the accelerator. Those at CERN never had any doubts that the LHC was safe. Safety reviews published in 2003 and 2008 both concluded that there was no danger that the particle collisions would lead to devastation. These reviews ultimately rested on the simple observation that higher-energy versions of these collisions take place billions of times each second in nature when cosmic rays smash into every object in the universe – bombardments that leave the Earth and all else intact. Indeed, since the collider restarted last November, it has generated record-breaking proton–proton collisions of 2.36 TeV without incident. Some people, however, remain unconvinced and have tried to halt the LHC through the courts. Plaintiffs have filed lawsuits in Switzerland, Germany, Hawaii and the European Court of Human Rights. However, to date, no action has resulted in a decision on the merits of the case. The Swiss lawsuit was dismissed because CERN straddles the Franco-Swiss border and the lab's treaties with France and Switzerland guarantee it immunity from legal process in both countries. The Hawaii suit was thrown out because the judge handling the claim ruled that US funding and participation in the LHC did not provide the Hawaii court with sufficient jurisdiction under the environmental law invoked by the plaintiffs.

|

| Article |

400 Years After Galileo When Galileo Galilei pointed his newly built telescope skyward in 1609, he transformed our view of the cosmos. Among his discoveries were mountains on the moon, spots on the sun, vast numbers of new stars and four satellites orbiting Jupiter. It was this last discovery in particular that convinced him that the Earth moves round the sun rather than vice-versa, since the orbit of the moons demonstrated the reality of rotation around something other than our home planet. But his discoveries brought him in direct conflict with the Catholic Church. The church taught that the Earth stood still at the center of the universe – and as a result condemned Galileo in 1633 for defending the heliocentric hypothesis and denying the scientific authority of the Bible.This conflict might now seem of purely historical interest. After all, we all know the Earth goes around the sun, and modern astronomical discoveries only seem to confer upon the Earth a less central position in the scheme of things – as a planet orbiting a medium-sized star in the outer reaches of a galaxy that is itself not in the center of a galaxy cluster. Indeed, the church itself has recognized the veracity of Galileo's arguments; Pope John Paul II admitted in 1992 that the church was in error when it insisted on the centrality of the Earth and in 2000 issued a formal apology for the trial of Galileo. The relationship between science and religion, however, clearly continues to create dispute. Recent years have seen the publication of many books by prominent atheist scientists pronouncing that God has no place in our modern world. And the debate over the teaching of intelligent design continues unabated. What, then, is the proper relationship between our understanding of nature and a religious faith? Does the former render the latter redundant? Can the two instead co-exist happily but separately? Or do they stand in some more complex relationship with one another? Discussing this question in the context of the Galileo affair, on the 400th anniversary of the Tuscan astronomer's groundbreaking observations, scientists, theologians and philosophers met two weeks ago at the Pontifical Lateran University in Rome. Part of the meeting was devoted to exploring the latest developments in cosmology and understanding how these relate to the |

| Article |

Fish Inspire Wind Farm Configuration Conventional wind turbines work best when located as far as possible from the destructive vortices of neighbouring turbines. However, a pair of scientists in the US have worked out that the performance of other kinds of turbine actually improves when they are placed close to one another, concluding that wind farms could therefore be made much smaller than they are today. The familiar propeller-like turbine with a horizontal axis of rotation can convert 50% or more of the energy from the wind that it is exposed to. In a wind farm, however, the wake from one turbine will disturb the air reaching the blades of its neighbours meaning that turbines must be placed far apart. Typically, to ensure that it generates about 90% of the power that it would in isolation, a turbine must be placed about three rotor diameters from its nearest lateral neighbours and around 10 rotor diameters from the turbine downstream. For a rotor with a diameter of 100 m this latter figure becomes 1 km – a considerable distance. A less familiar family of turbines have a vertical axis of rotation. It includes a number of different sub-types, including those that use drag to push the device around and others that use aerofoils to generate lift. Individually, these vertical-axis turbines are less efficient than the horizontal-axis devices because only part of the turbine can be pushed by the wind at any one time, and they have therefore proven far less popular. However, these turbines have a significant advantage over the horizontal-axis variety – their power output can be increased when they are placed very close to one another. How fish save on energyNow, Robert Whittlesey and John Dabiri of the California Institute of Technology have worked out how best to arrange such closely spaced turbines by drawing on the work of aeronautical engineer Daniel Weihs, who showed in the 1970s how fish save on energy by swimming within schools. Such fish form a series of offset rows, and Weihs found that fish get carried forward by the vortices created by the swimming motion of their two closest companions in the row immediately in front of them. Whittlesey and Dabiri wondered whether the relative spacing of vortices produced by an individual fish might serve as a good template for the arrangement of vertical-axis turbines within a wind farm and set up a computer model to test this idea. |

| Article |

Can We Really Build an Artificial Brain? The four black refrigerator-sized boxes in a basement of the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland bear very little resemblance to a human brain. Each box contains some 2,000 microchips lined up on shelves, rather than the grey matter found inside our heads. However, biologist Henry Markram and colleagues in Lausanne believe that a more powerful version of this computer can simulate the workings of the brain. They say they will be able to create such a simulation within 10 years, that this artificial brain should show the hallmarks of intelligence – such as speech, planning and learning – and that it will simulate emotions and maybe even consciousness. Claims that thinking machines are just round the corner are nothing new. The computer HAL 9000 in Arthur C. Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey was based on predictions by leading scientists about how real-life computers would actually evolve by the turn of the millennium. Indeed, in 1965, artificial intelligence expert Herbert Simon predicted that within 20 years, machines would be capable of "doing any work a man can do". Of course, such predictions have proved to be woefully wide of the mark, and artificial intelligence, or AI, researchers have suffered frequent funding cuts from skeptical governments. Some predictions have come to pass, such as the forecast that machines would eventually outstrip humans at chess, with IBM's Deep Blue computer beating grandmaster Garry Kasparov in 1997. This success of Deep Blue is, however, not particularly significant in the wider picture. It had no idea of strategy and for each move simply calculated vast numbers of permutations using pre-defined algorithms. It certainly wasn't thinking like a human. Markram's group says that it differs from previous efforts to mimic human intelligence by simulating the actual biology of the brain. Usually, AI researchers focus on logical structures rather than worrying about messy biology. Artificial neural networks, for example, consist of entities that function like the nervous cells, or neurons, in a brain, in that each receives electrical inputs from a number of |

| Column |

Darwin's Bridge to GodReaction of the Church to the Origin of Species has moved in the 150 years since its publication from proscription to an admission that it is more than a hypothesis. Catholic thinkers gathered to discuss how the theory fits with Catholic teaching.  Continuous and often strident opposition by religious believers to Darwin’s theory of evolution has marked the past century and a half. The heartland of this opposition has been the United States, where so-called "Creation science" was born and where "intelligent design", an attempt to demonstrate the need for a designer in nature, has taken hold. However, religious opposition to Charles Darwin’s ideas have in recent years become a feature in many other countries around the world. Yet some biologists argue just as stridently as the creationists that Darwinian evolution is all we need to explain man’s place in nature and that this scientific idea makes God redundant. It was against this background that the Vatican hosted a conference in honour of Darwin at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome earlier this month entitled "Biological evolution: facts and theories". The aim of the meeting, according to the organisers, was to give scientists, philosophers and theologians the opportunity to discuss the progress and implications of evolutionary biology without, on the one hand, turning ideas about Creation into scientific theory or, on the other, reducing evolutionary thinking to scientific dogma. Plotting such a course is a tricky business. As Fr Rafael Martínez of the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome told the conference, the Catholic Church has itself not always been entirely reasonable in its response to Darwin’s ideas. Martínez pointed out that although there was no Galileo-style condemnation in the case of evolution, the Church did place a number of books sympathetic to Darwin’s ideas on its Index of Prohibited Books. The Church’s position on evolution softened in the twentieth century, moving from a policy of no comment, through saying – in the 1950s – that it did not forbid research on the subject, to the statement by Pope John Paul II in 1996 that evolution is "more than a hypothesis". Darwin’s theory of evolution – descent with modification through natural selection – is remarkably simple. "Descent with modification" refers to the gradual emergence of new species over time from changes to previously existing species. "Natural selection" is the process responsible for these changes. It means that over time the average fitness of creatures increases, leading to new species. |