Beliefs to Behavior

The Hodge Hill Prophecy

What's really behind the British riots?

Between 2005 and 2010, a team led by Birmingham University education Dean James Arthur launched a character education project called Learning For Life, the first of its kind in Great Britain. Building from a base of solid social science research, Learning For Life seeks to build and strengthen character in families, schools, universities, and on the job. Learning For Life, which was funded by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation, included a comprehensive 2007 survey of character attitudes among disadvantaged English youth in Birmingham’s Hodge Hill constituency and others like it across the UK. To read it today, in the aftermath of youth rioting and looting that shook major British cities, is to encounter a kind of prophecy. Prof. Arthur spoke to us from his home in England after a tumultuous week.

As the principal researcher on the Learning for Life project, were you surprised by the violence and looting that swept England?

Not really. I was surprised by the extent of it, but I was not surprised that young people don’t feel a part of society. They also generally do not engage positively in their communities, the exception being Muslim children. The reasons are quite complex, and there’s not an easy answer to the whole thing. I don’t for a second think it was economic. Well over half of [looters] were under the age of 18. Clearly the vast majority of them are not the kind of people who had any sort of higher education. We’re not talking about people who had been at university. We’re talking about a large group of people who have not gained serious qualifications to participate in society. They are young people who live in the most socially and economically deprived areas of our cities.

You’ve got these two groups, poor Afro-Caribbeans and poor whites, who were the main participants in the riots. When I did my research in schools across England, we discovered that it was precisely many of these disadvantaged white children and Afro-Caribbean black children that had the least respect for the basic virtues in civil society — and these were the groups that mainly rioted.

My research found that these children were less happy and less optimistic about the future, and they didn’t feel that they belonged to civil society. They were also less positive about the virtues — honesty, trustworthiness, courage, justice and others. They also had far fewer aspirations for their future compared with other groups.

The C of E's Response to the Riots Has Cemented its Role in Society

Yes, there were soundbites, but the Church of England is demonstrating its value as a social body.

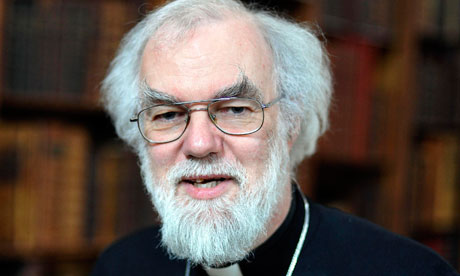

Rowan Williams, the archbishop of Canterbury, and Richard Chartres, the bishop of London, have both spoken powerfully in the aftermath of the riots: condemning the criminality, and asking what can be done to rebuild parenting skills and education in the communities affected. They feel that the church is among the biggest parts of society's response to the riots.

Williams, speaking in the House of Lords, said: "There is nothing to romanticise and there is nothing to condone in the behaviour that has spread across our streets. This is indeed criminality – criminality pure and simple."

It looks as if someone has at last spoken to him sternly about the danger of giving hostages to the Daily Mail. He has remembered to get his condemnation in before coming to all the squishy bits about understanding. He certainly didn't mention forgiveness. When he did talk about understanding the causes of the riots, it was in the context of preventing future ones, rather than excusing anything.

For Williams, the cure for further outbreaks could only be found in the long-term and in the reorientation of schools towards teaching virtues rather than skills: "Over the last two decades, our educational philosophy at every level has been more and more dominated by an instrumentalist model; less and less concerned with a building of virtue, character and citizenship – 'civic excellence' as we might say. And a good educational system in a healthy society is one that builds character, that builds virtue.

"Character involves … a deepened sense of empathy with others, a deepened sense of our involvement together in a social project in which we all have to participate.

"Are we prepared to think not only about discipline in classrooms, but also about the content and ethos of our educational institutions – asking can we once again build a society which takes seriously the task of educating citizens, not consumers, not cogs in an economic system, but citizens."

Chartres picked up the same note but more practically: "Those who went on the rampage … seem to lack the restraint and the moral compass which comes from clear teaching about right and wrong communicated through nourishing relationships. The background to the riots is family breakdown and the absence of strong and positive role models."

Carl Jung, part 7: The power of acceptance

Like the AA movement, Jung believed that acceptance and spiritual interconnectedness were crucial to a person's recovery.

In 1931, one of Jung's patients proved stubbornly resistant to therapy. Roland H was an American alcoholic whom he saw for many weeks, possibly a year. But Roland's desire for drink refused to diminish. A year later Roland returned to Zürich still drinking, and Jung concluded that he probably wouldn't be cured through therapy.

But ever the experimenter, Jung had an idea.

Roland should join the Oxford Group, an evangelical Christian movement that stressed the necessity of total surrender to God. Jung hoped that his patient might undergo a conversion experience, which, as his friend William James had realised, is a transformative change at depth, brought about by the location of an entirely new source of energy within the unconscious. That might tame the craving.

It worked. Roland told another apparently hopeless alcoholic, Bill W, about the experience. Bill too was converted, and had a vision of groups of alcoholics inspiring each other to quit. The Society of Alcoholics Anonymous was formed. Today it has more than 2 million members in 150 countries.

I spoke to a friend of mine who attends meetings of Narcotics Anonymous to understand more about the element of conversion. "It's hugely important," he said.

His addictions had been fuelled by a surface obsession with career and money, and a deeper anxiety that nothing was right. "It's the first time I'd been prompted seriously to consider something bigger than myself."

Calling the experience "spiritual" seems accurate too, because a meeting is about more than gaining a circle of supportive friends. "I have friends," my friend remarks, before continuing that the focused intention of a meeting is about something else: their connection to a very powerful force. "I can't picture it, I can't name it," he says, before adding, "I've never given much thought to church." Narcotics Anonymous literature expresses it more formally: "For our group purpose there is but one ultimate authority – a loving God as He may express Himself in our group conscience."

If You Want Big Society, You Need Big Religion

Faith communities may encourage their members to contribute to society – but can politicians harness their benefits?

Robert Putnam, Harvard professor of public policy, has been in London, channelling the wisdom of social capital at No 10, as well as talking at St Martins-in-the-Fields on Monday evening. That venue is the big clue to his latest findings. It could be summarised thus: if you want big society, you need big religion.

In the US, over half of all social capital is religious. Religious people just do all citizenish things better than secular people, from giving, to voting, to volunteering. Moreover, they offer their money and time to everyone, regardless of whether they belong to their religious group.

It could be, of course, that the religious already have the virtues of citizenship. However, Putnam believes the relationship is causal, not just a correlation. Longitudinal studies also show as much. So why?

He argues it's not to do with belief, but with being part of a community of belief. An atheist with several churchgoing friends will be a better citizen too. In fact, churchgoing friends are what he calls "supercharged" when it comes to citizenship. Working out just what a religious community gives would be key to generalising the findings beyond faith.

What Science Tells about Power and Infidelity

On tonight's All Things Considered, NPR's science correspondent Shankar Vedantam takes on a subject we've been covering quite a bit lately: Powerful people caught up in scandals. Anthony Weiner, John Edwards, Arnold Schwarzenegger — men behaving badly, right? It may be more complex than that. Research shows power causes men and women to take risks and imagine themselves as more attractive. New survey research shows that, given power, women are as likely as men to stray.

MELISSA BLOCK, host:

And Mark Sanford is one of the cascade of politicians linked to sex scandals. If you print out the Wikipedia page for federal political sex scandals, in the U.S. alone, it runs to six single-spaced pages. And recently, it's gotten two names longer, both of them congressman from New York.

NPR science correspondent Shankar Vedantam explains why so many powerful people get caught up in sexual indiscretions.

SHANKAR VEDANTAM: The confessions we've heard in recent years from powerful men and sex scandals all sounded alike. Listen to Congressman Anthony Weiner, Senator John Ensign, governors Eliot Spitzer and Mark Sanford, and Senator David Vitter.

listen now or download All Things Considered

Expanding Horizons for Arabic Children

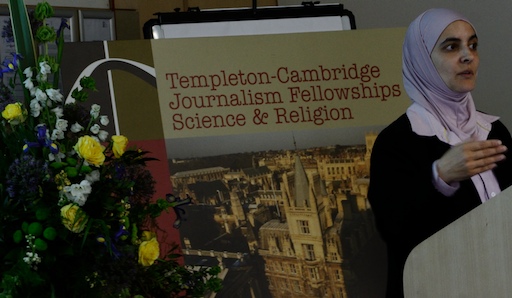

We're accustomed to seeing people reading for pleasure wherever we go: on the subways, in airports, at the beach. We take it for granted: reading as one of our main forms of entertainment. But Rana Dajani, a biologist who spent much of her childhood in the U.S., didn't realize how much it was missing from her homeland in Jordan until she was back, raising her own children.

"There was a survey done by the Arabian news," she told me, "that stated Arabs read on average half a page a year compared to eleven books a year in the U.S. But it is a common observation that no one read, and I only did. Also my daughters, they only read."

She added, "My daughter once said she can't wait for a day when her class mates don't ask her why she reads but what she reads."

In Jordan, Saudi Arabia and elsewhere in the Middle East, she said, people read for study, for school and for their jobs. But not for pleasure.

Reading for pleasure was such a key component of her own life, and that of her children, that Dajani felt she had to do something.

She invited a small group of children in her neighborhood to gather and listen to her read stories aloud to them.

"I thought of inviting children to my house at first," she told me. "But that wasn't an option for the long term. We needed a public place, where the children and their parents would feel they were safe."

The obvious place was the mosque. "By implementing our initiative in local mosques," Dajani said, "we are essentially turning mosques into community centers opening the doors to everyone. In the Middle East, the idea of reading to a child is a new concept, as there is little emphasis on reading for pleasure outside of academic or religious contexts. We are transforming these attitudes by inspiring children and their parents to read for pleasure."

It is now five years since she launched her program. We Love Reading has since sprouted reading groups and homegrown libraries in towns all over Jordan, as well as Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Tunis, Turkey and expanding beyond to Malaysia. "I train someone and tell them don't pay it back, but pay it forward," she said.

Tunisians' Welcoming of Libyan Refugees is Altruism in Action

Tunisian willingness to house fleeing Libyans reminds us that caring for others is really a human, not a technical, act.

Many tens of thousands of refugees have now fled Libya and crossed to the relative safety of Tunisia. Their stories will, no doubt, be ones of terror and horror. And yet, there are tales of deep humanity too in their flight. A UNHCR spokesperson, Andrej Mahecic, has reported that fewer than one in ten of the Libyan arrivals are staying in refugee camps. Instead, the vast majority of those fleeing have been welcomed by Tunisian communities. The homeless Libyans are being hosted by locals, at the locals' expense and with great generosity, given the Tunisians' own resources are not great.

It's a moving tale, especially given the worries rattling around rich Europe about the migration implications of the Arab uprisings, given our own habits of locking up immigrants behind bars. Of course, the situation in Libya is an emergency. And there are deep bonds between these peoples, founded upon a common religion. But the story prompts thoughts about the nature of altruism and what happens when caring for others comes to be seen as primarily a technical, rather than a human, problem.

There is a lot of discussion about altruism today, driven in large part by the trouble it causes evolutionary theory. In the dog-eat-dog world of crude Darwinism, why should it be that some species collaborate, even to the point of self-sacrifice? In fact, Martin Nowak, author of SuperCooperators, argues that co-operation is quite as central to evolution as competition. You only need do the maths, he explains, the cost-benefit analysis. Working together in groups works. Only, that's not the whole story, he continues.

After Tsunami, Japanese Turn To Ancient Rituals

The Japanese are beginning memorial ceremonies for people killed in the earthquake and tsunami. Times of crisis lead many people to turn to religion for strength and comfort. In Japan, the focus will be on honoring the dead, and moving on with life.

On Monday, Tokyo Gov. Shintaro Ishihara startled many when he said, "The Japanese people must take advantage of this tsunami to wash away their selfish greed. I really do think this is divine punishment."

The governor soon apologized. But people were shocked, not just because it seemed to blame the victims — but also because it is so at odds with the beliefs of modern-day Japanese.

Moving Beyond The 'Why'

"They know about tectonic plates, geography, geology — they know why tsunamis happen," says John Nelson, an expert on Asian religions at the University of San Francisco.

"And they don't need some governor to say it's the will of heaven that this happened," he says.

Nelson says that while Japanese society is largely secular, events frequently drive them back to ancient traditions.

"There's a famous saying in Japanese that, 'People turn to the gods in times of trouble,' " he says. "And I think we'll see that here."

The rituals of Shinto and Buddhism permeate Japanese life. And in these two belief systems, scholars say, people do not focus on why the tragedy happened, but on how they should proceed.

After Deaths, Buddhist Rituals

Duncan Williams is a Buddhist priest who just returned from Japan. "We can't pinpoint exactly what brought this about," Williams says. "I think the takeaway is that, for Buddhists, it almost doesn't matter what caused this situation; what's important is the response."

listen now or download Morning Edition

Forgiveness Scholar Opens Up On Role Of Faith

VATICAN CITY (RNS) For more than a quarter of a century, psychologist Robert D. Enright has been a pioneer in the scientific study of forgiveness -- the kind of guy Time magazine once dubbed "the forgiveness trailblazer."

He's probed the mental and physical benefits that incest survivors, adult children of alcoholics, cardiac patients and others can enjoy if they choose to show mercy to those who have done them wrong.

His work has taken him to global hotspots, with a schools program of "forgiveness education" for Catholic and Protestant children in Northern Ireland, and a new project to promote e-mail dialogue among Jewish, Muslim and Christian children in Israel and Palestine.

But while forgiveness carries strong associations with religion, Enright has always supported his claims with empirical data alone, insisting that his method is usable by "theists and nontheists" alike.

The study of forgiveness has nevertheless ended up nurturing Enright's own faith, ultimately bringing him back to the Roman Catholic Church of his youth. He is now preparing, for the first time, to make that faith explicit in his work. Enright was not a churchgoer when he embarked on this line of research in 1985, but as he tells it, his discovery of the field that would define his career came in answer to a prayer.

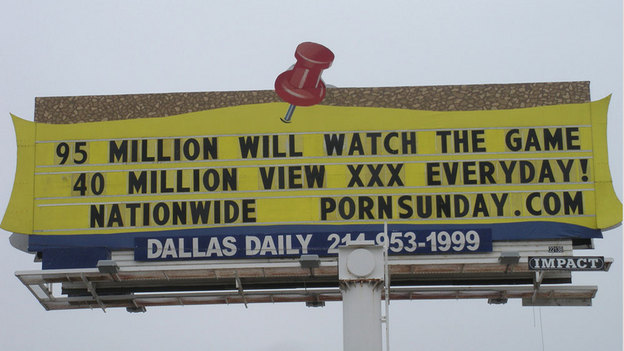

Religious Groups Tackle An X-Rated Secret

This Super Bowl Sunday, church may be as jarring as a quarterback sack for some worshippers who, after settling into their pews, discover that the subject of the morning's sermon is pornography.

More than 300 churches are expected to celebrate National Porn Sunday on Feb. 6. The members will watch a video sermon featuring current and former NFL players talking about their struggles with pornography.

"No one knew my problem was this bad," former New York Jets wide receiver Eric Boles says in the video.

"I would go home, and I would sit there, and the laptop and I would have a conversation," says Josh McCown, who played quarterback for several NFL teams, most recently the Carolina Panthers. "And I would battle with not even wanting to open it, not even wanting to check e-mails because I knew where it might lead me."

"I mean, you go to MSN or CNN or MSNBC," adds quarterback Jon Kitna of the Dallas Cowboys, "and you see this, and it leads to a link to this, and pretty soon I'm into a world that I never knew existed."

Elephant In The Pews

Presence Church in Addison, Texas, will be one of the churches playing the video on Sunday. Steven Kirlin, the church's pastor, hopes that seeing football stars talk about pornography will break a taboo.

"I think that opens up others to say, 'Well, I'm not only going to give this a listen, but I might actually feel a little more free to talk about this because these guys are willing to talk about it,'" Kirlin says.

Pornography is the elephant in the pews, says Craig Gross, who produced the video and whose sermon is featured in it.

"The statistics say that 48 percent of Christian families are dealing with the issue of pornography in their home," Gross says. "I would say the other 52 percent are just unaware of it being an issue in their house."

listen now or download All Things Considered

The Return of Virtue Ethics

What is the good life? How can we know?

The Enlightenment was a revolution in the way we think about morality. Two ethical models, in particular, have come to dominate ever since. One can be traced back to Immanuel Kant, and is based upon the notion of duty (and hence is called deontological, from the Greek deon, meaning duty.) The second is hedonist and can be traced back to Jeremy Bentham, and his principle of utility: an action can be called good if it increases pleasure or decreases pain.

Put them together and you have the liberal approach to asking what’s the right thing to do. It’s liberal not in the sense of being pro-gay or pro-abortion. Rather, it’s liberal in the deeper sense of focusing on the individual and the choices an individual makes. It's ethics conceived of in terms of rights and responsibilities, or in terms of what makes you happy or sad. The philosopher John Stuart Mill summed it up when he wrote: "Neither one person, nor any number of persons is warranted in saying to another human creature of ripe years, that he shall not do with his life for his own benefit what he chooses to do with it."

You can understand why Mill wrote what he did. He lived in a period of history in which many people were not free to do as they chose. They were ruled by monarchs and chastised by prelates. The result was the subjugation of women and the owning of slaves. But we don’t live in such a world now. Most enjoy a degree of freedom that would have been unimaginable for most of human history, in the West at least. As a result, the liberal approaches to ethics are increasingly being questioned. Can they tell us what this freedom is for? Is it for more than just more consumption, more accumulation? What is the good life?

The problem is that we’ve lost touch with the bigger picture: what is it that makes life good for us humans? The Enlightenment left us with few resources for thinking about that larger question, because it was so focused on winning individuals their freedom. The philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe described our dilemma this way. Our talk of having "moral duties," or our description of actions as "morally right," has become vacuous because we are now free of the law-giving God who fixes those duties and obligations. And Anscombe, as a Catholic, was a firm believer in God — only not a law-giving God but a loving one.

In any case, now that we are relatively free, we need to ask again what life is for. There is another ethical tradition that can help. It’s known as virtue ethics. Virtue ethics begins by asking what it is to be human, and proceeds by asking what virtues — or characteristics, habits and skills — we need in order to become all that we might be as humans. It’s much associated with the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, who discussed the meaning of friendship as a way to illustrate his approach to ethics.

Science tells us we are social animals, Aristotle observed. But in order to live well as social animals, we also need a vision of what our sociality can be. He had a word for that vision: friendship. The good friend is someone who knows themselves, who is honest and courageous, who has time for others, who is engaged not only in their self-interest but has a concern for others. These are some of the virtues we should nurture in order to be fulfilled as friends.

For These Young Nuns, Habits Are The New Radical

For the most part, these are grim days for Catholic nuns. Convents are closing, nuns are aging and there are relatively few new recruits. But something startling is happening in Nashville, Tenn. The Dominican Sisters of St. Cecilia are seeing a boom in new young sisters: Twenty-seven joined this year and 90 entered over the past five years.

The average of new entrants here is 23. And overall, the average age of the Nashville Dominicans is 36 — four decades younger than the average nun nationwide. Unlike many older sisters in previous generations, who wear street clothes and live alone, the Nashville Dominicans wear traditional habits and adhere to a strict life of prayer, teaching and silence.

They enter the chapel without saying a word, the swish of their long white habits the only sound. It is 5:30 in the morning, pitch black outside — but inside, the chapel is candescent as more than 150 women kneel and pray and fill the soaring sanctuary with their ghostly songs of praise. A few elderly sisters sit in wheelchairs, but most of these sisters have unlined faces and are bursting with energy. Watching them, you wonder what would coax these young women to a strict life of prayer, teaching, study and silence.

And did they always want to be nuns? "No," says Sister Beatrice Clark, laughing. "I didn't know they still existed." Clark, who is 27, says she became aware of the religious life when she was a student at Catholic University in Washington. In her junior year, she began feeling that God was drawing her to enter a convent. Over Thanksgiving vacation in 2004, she broke the news to her family.

"My parents just sat there and looked at me," she says. "And they cried. And I said, 'I think I'm supposed to enter soon.' And my father said, 'This is the time of life to take leaps.'" She joined the Nashville Dominicans on her 22nd birthday.

Silence — Sometimes

The sisters eat breakfast in silence, sitting side by side at long tables, served by the novices in white habits and veils. Sister Joan of Arc, who's 27, stoops to pour coffee. At 6 feet, 2 inches, the former basketball player for the University of Notre Dame is hard to miss. Sister Joan of Arc, who was born Kelsey Wicks, like the others here adopted a new name when she entered. She says she worked on refugee issues after college, then received a scholarship to Notre Dame Law School. But her plans shifted when she went on a medical mission trip: In Africa she saw abject physical poverty, but it was nothing compared with the impoverishment she saw when she came home.

listen now or download Listen to the Story: All Things Considered

Faith-Based Fundraisers

In times of crisis and natural disasters, many are eager to donate. But fundraising for chronic diseases and global troubles such as hunger or a lack of clean water can be more of a challenge. So faith-based groups have gotten creative.

They use ingenuity and strategies true to religious teachings to reel in first-time givers and conquer giving fatigue in regular donors by linking up to holy days and life cycle celebrations.

Here's a look at three groups that make giving easy, faithful — and joyful.

The Advent Conspiracy

Three evangelical pastors were fed up with Christmas because "its meaning, beauty and holiness had been sucked clean and dry," recalls Tony Biaggne, creative director for Windsor Crossing Community Church in Chesterfield, Mo.

Out of their shared complaints, the Advent Conspiracy was born in 2006 and became an annual worldwide effort to embody the spirit of Advent's four weeks of prayerful focus before Christmas.

Pastors Greg Holder of Windsor Crossing, Chris Seay of Ecclesia Church in Houston and Rick McKinley of Imago Dei Community in Portland, Ore., came up with the campaign's four themes: to worship fully, to spend less, to give "more gifts that matter" and to "love all," Biaggne says.

The Crossing donated "every dollar, dime and check" to Living Water, a Houston-based non-profit group that addresses water needs village by village worldwide, he says.

William James, Part 5: Saintliness

Religious experiences, and their saintly effects, are morally helpful, not damaging or repugnant.

One of Friedrich Nietzsche's fiercest attacks on Christianity pitches against the exalted virtues of saintliness. He believed the worship of the crucified encouraged a vile, slave mentality in its adherents. It's partly a result of being required to submit to a superior deity; partly a result of the moral demand to serve others. Christianity, he concluded, is dehumanising.

He has a point. Consider what might happen should you take pity on someone, as the Christian ethic of love requires. This virtue, Nietzsche insists, is really the desire to take possession. Thus, when we see someone who is suffering, and act on a feeling of compassion, we make ourselves their benefactor. We set ourselves over them, and leave them in need of us. We might not only congratulation ourselves for our sympathy, but could well prefer attending to the suffering of others to facing our own distress – the phenomenon of the wounded healer who helps others because they cannot help themselves.

Far better, Nietzsche thought, that individuals pursue their own way through suffering – though not in isolation. Rather, do so together, and so learn to rejoice, in spite of it all. That way suffering is not spread, and joy might be increased.

This was a conclusion that worried William James, and in the The Varieties of Religious Experience he devotes five lectures to challenging it. It troubled him because he was keen to show that religious experiences, and their saintly effects, are morally helpful, not damaging or repugnant. "The highest flights of charity, devotion, trust, patience, bravery to which the wings of human nature have spread themselves have been flown for religious ideals," he avers. He sets out on a lengthy analysis of cases to prove his point.

Praying for the Poor

The Micah challenge marks a turn towards social justice from one of the most traditionally conservative kinds of Christianity.

In the light of recent discussion of prayers, it's worth considering that 60 million evangelical Christians around the world will be praying for justice around the world in the hope of abolishing extreme poverty. Leaving God out of it, as they would not wish to do, this is still an impressive and potentially important ritual, because it marks a turn towards social justice from one of the most traditionally conservative kinds of Christianity.

In this country, this "Micah challenge" is spearheaded by Joel Edwards, who ran the Evangelical Alliance for 11 years. As such, he had to navigate between extreme fundamentalists and liberal social justice types, something he managed with some skill. But if he's right about this movement, even the most theologically conservative elements are now moving in the direction of greater social responsibility.

"Starting with elements of the church who are steeped in personal piety, and or whom anything beyond prayer and personal self-improvement is no go," he says. Moving in to many more Christians who have over the last 10 years accepted that social action is an integral part of our gospel – feeding the poor, clothing the poor, building a hospital in Africa ... But now we are about advocacy for the extreme poor." This is a technical term referring to the 1.2 billion people around the world who live on less than $1.25 a day. They are, of course, found in the countries where evangelical religion of all sorts is thriving most.

"We want to bring our moral and infrastructural presence, our biblical convictions, not for our own sakes, but on behalf of the extreme poor."

John Henry Newman's Last Act of Friendship

Why the beatified cardinal wanted to be buried with Ambrose St John is disputed, but for me this was an act of 'sworn brothers'

Why was John Henry Newman buried in a shared grave with Ambrose St John? It was his express wish – of St John he wrote: "From the first he loved me with an intensity of love, which was unaccountable" – and has been used to claim he is a gay saint. That's clearly anachronistic and, to my mind, distorts and abuses the significance of Newman's last act, which was actually about friendship.

Newman was self-consciously adopting a tradition of centuries, whereby individuals, now called "sworn brothers", were buried together beneath epitaphs such as: "In life united, in death not divided." It was not a romantic gesture, but a theological statement. Committed friendship in life had been for them a foretaste of communion in heaven. It's a view brilliantly expounded in Alan Bray's The Friend.

Bray's conclusion is inevitably speculative when it comes to Newman in particular. Newman didn't leave unequivocal evidence about what he was doing, though the circumstantial evidence is compelling. And more so, I think, than an alternative thesis in this month's Standpoint.

It's penned by Dermot Fenlon, the academic Oratorian who was expelled from the Oratory and banned from the Newman beatification ceremony. There's nothing of that in the piece. Instead, Fenlon outlines a view of communal burial based on the notion of ad sanctos.

Christianity is an incarnational religion, which means that the material world matters. Holy places, in particular, are routinely visited and venerated, none more so than sites where saints are buried. Further, Christians have long sought to be buried near saints – the practice of ad sanctos. Fenlon outlines this tradition and argues that this is what Newman wanted to imitate. It was not friendship but sanctity he sought to express.

Adoption Season for Evangelicals

A biblical mandate to help children, especially those in foster care.

Last Saturday at Grace Chapel in Denver, Focus on the Family (in collaboration with the Colorado Department of Human Services) hosted an information session for parents interested in adopting children out of the foster-care system. More than 150 families were represented and 55 of those have already begun the process. It was a successful and fitting end for the summer of 2010, which turned into a season of adoption for evangelicals.

In May, megachurch pastor Rick Warren held a "civil forum" on the subject. An audience of 800 attended and thousands more watched the webcast from their homes. "Orphans and vulnerable children are not a cause," said Warren. "They are a biblical and social mandate we can't ignore. A country half the size of the U.S—that's how many orphans there are in the world. We're not talking about a small problem."

Adoption was the cover story of Christianity Today in July. It included a feature by Russell Moore, dean of the School of Theology at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, in which he described in heart-wrenching terms the circumstances of his own adoption of two brothers from a Russian orphanage.

Mr. Moore, the author of a book called "Adopted for Life: The Priority of Adoption for Christian Families and Churches," has become a sort of go-to person for evangelicals on the issue of adoption. In trying to explain why Christians have a particular duty to adopt, he told me that "every one of us who follows Christ was adopted into an already existing family."

Which is to say that unlike Judaism or Islam, faiths that one is born into, Christianity requires each member to have an individual relationship with Christ. And so, in that sense, it is as if each Christian is adopted.

Is Monogamy the Root of All Equality?

An examination of the effects of polygamous marriage suggests it's bad for everyone in society, not just women.

Does polygamy between consenting adults harm anyone else? The question has been raised in Canada, where polygamy has been illegal since the nineteenth century, but the supreme court in British Columbia is going to have to decide whether this law is unconstitutional. Doesn't it infringe the right of adults to arrange their lives by mutual consent? The original law was directed against Mormons, and the present test is also directed against a polygamous fundamentalist Mormon commune. Islam does not seem to have played a major part in the debate there, as it undoubtedly would here. But the interesting thing is that libertarians here line up with the most authoritarian religious groups: most of the motions filed to the court in favour of polygamy come from modern polyamorous groups.

However, there has been one brief filed against decriminalising polygamy, and it comes from a most remarkable source: the anthropologist Joe Henrich at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. This has been the source of much of the most interesting and solid scientific research on religion in the last ten years. Henrich himself has an upcoming paper on Why people believe in God but not in Santa Claus, or Zeus.

The particular merit of this school is that it refines the ideas of evolutionary psychology to take cultural norms just as seriously, and to look at group level competition, which is mediated by culture, quite as seriously as individual competition within groups. Polygamy is a fascinating test case for this approach because the benefits all accrue to the alpha males who end up with most women, whereas the costs are paid by everyone else, and by society as a whole.

In a long affidavit to the court, Henrich considers the social and psychological benefits of monogamous marriage. These aren't widely accepted: using the larget available database of anthropological surveys Henrich concluded that 85% of human societies allow high-status men to have more than one wife. It;s important to notice that this is different from the observation that men (and women) will cheat on each other. That's mating behaviour, which Henrich distinguished from marriage, which is a set of socially accepted and enforced norms and arrangements. In fact he writes that "given our evolved mating psychology, the puzzle is not why societies are polygynous; it's why any society is monogamous, especially one in which males are highly unequal, (like ours)."

The answer he gives is that monogamy gives huge advantages to societies which practice it. It arose, like philosophy, among the Greeks, passed through the Romans, and then the Christian church took it over as an ideal and managed over the course of around a thousand years to establish it as the norm in Europe, even for the aristocracy.

Questions for the Cardinal

The resignation of the Bishop of Bruges after he admitted abusing a young boy unleashed a chain of events culminating in a police raid in Brussels. The scandal surrounding allegations of clerical abuse now threatens to engulf Cardinal Denneels.

Belgium’s bishops met on Thursday 24 June, and there was no reason to think that the monthly meeting would be different from any other.

They had gathered at the Archbishop’s Palace in Mechelen, just outside Brussels, and were settling down to business when a team of police officers arrived.

The police said they were authorised to search the premises as part of an investigation into sexual abuse by priests of the diocese. The bishops and the diocesan staff had to stay where they were for nine hours, their mobile phones confiscated, while inspectors searched the offices and took away a computer. At the same time, other police raided the nearby flat of Cardinal Godfried Danneels and seized his computer. A third team searched the Leuven offices of the Church’s commission of inquiry into child abuse. In a bizarre move, officers even visited the crypt of St Rumbold’s Cathedral in Mechelen. A church spokesman said they drilled into the tombs of two archbishops, Cardinals Leo Jozef Suenens and Jozef-Ernest van Roey, and inserted a tiny camera to search inside. The Brussels prosecutor’s office disputes this, saying that only one tomb was disturbed.

The police raids highlight the growing tension between Church and State in Belgium that has emerged since the Bishop of Bruges, Roger Vangheluwe, resigned in April after admitting sexually abusing his nephew.

Another consequence of Vangheluwe’s resignation was an increase in calls to the Belgian Church’s abuse hotline. By last week the commission on child abuse had built up 475 dossiers or cases – all of which were seized in the police raids. Bishop Vangheluwe’s disgrace also threatens the reputation of Cardinal Danneels, until recently a much-loved figure who was Archbishop of Brussels-Mechelen for more than 30 years until his retirement last January. Did he know anything about his friend’s crimes and if he did, was he aware that other diocesan priests had also abused children? Conflicting answers have been given to these questions.

The Belgian media believe the cardinal was involved in a cover-up. "The Danneels Code," the Brussels daily De Standaard headlined one front page alongside a picture of the cardinal. An article was entitled "Searching for Danneels’ hiding places."

Cardinal Danneels said after Bishop Vangheluwe’s resignation that he had only learned about the case shortly before it became public. Asked about this after the raids, Danneels’ successor, Archbishop André-Joseph Léonard, said he had no reason to doubt what his predecessor had said.

The Dalai Lama on Violence

The Dalai Lama's message for Armed Forces Day may surprise those who assume him to be a pacifist.

The Dalai Lama has sent a message of support for Armed Forces Day, which is next Saturday. In it, he writes of his admiration for the military. That is perhaps not so surprising. As he explains, there are many parallels between being a monk and being a soldier – the need for discipline, companionship, and inner strength.

But his support will take some of his western admirers by surprise, not least when it comes to his thoughts on non-violence.

Attitudes towards violence in Buddhism are enormously complex. There are some traditions that argue aggression, and killing in particular, is always wrong. But there are others which argue that killing can be good, when executed by a spiritually skilled practitioner who can do so with the right motivation. Tibetan Buddhism falls squarely into the latter tradition, and previous incarnations of the Dalai Lama have been such practitioners. The 13th, for example, modernised the Tibetan army.

What the present Dalai Lama argues, in his message of support, is that violence and non-violence are not always what they seem. "Sweet words" can be violent, he explains, when they intend harm. Conversely, "harsh and tough action" can be non-violent when it aims at the wellbeing of others. In short, violence – "harsh and tough action" – can be attitudinally non-violent. So what should we make of that?

Reviving Rural Minnesota

Some small towns with big ideas--immigration, sprucing up, co-oping

But here's the lament we shared during the breaks: It's no longer true that everyone living in urban Minnesota has ties to rural Minnesota — has a grandmother or an uncle living on a farm where city kids can learn to collect warm eggs in the chicken coop and watch the miracle of birth in the barn. Sure, we celebrate our rural cultural heritage at the State Fair every summer. And we indulge our need for a collective memory with the pretense of life in the prairie town of Garrison Keillor's fantasy.

The truth is, though, that to maintain a cohesive culture and an economy that can thrive statewide, we have to work at it. That's what drew more than 200 people to University of Minnesota Morris campus for the Symposium on Small Towns & Rural-Urban Gathering.

Century of loss

Everyone there knew the history lesson:

In 1900, two of every three Minnesotans lived in a rural area, most of them on farms.

In 2000, three in four Minnesotans lived in an urban area. And only 3 percent lived on a farm.

Young people led the exodus. And the towns they left behind gradually aged to the point where deaths outnumbered births each year.

The survivors were far more likely to be poor. Minnesota ranked among the nation's highest income states in 2000 with per-capita earnings of $23,198. Taken alone, though, Minnesota's rural cities would have ranked near the bottom with a per-capita income of $17,880, according to a report [PDF] by the Center for Small Towns on the Morris campus.

If you are reading this article on a computer in a metro area, you may say "So what?" When I think about the answer, I think about the argument we made over the years for empowering women in the workplace: A society can't reach its full economic potential if half of its workforce is under-employed. In the same sense, a state is squandering a good portion of its economic power if one-fourth of its people lack opportunities to thrive.

Spiffing up, fighting and leveraging

The big take-away message from the symposium was that some small cities and towns aren't sitting back waiting to die. Some are spiffing up to serve as bedroom communities where workers in regional centers can buy more housing for less money and raise their kids in that idyllic setting of Minnesota Past.

Some see a future in telecommuting, and they are fighting for access to broadband networks that can free up workers to live in scattered locations.

Some are leveraging resources to rebuild everything from cultural amenities to small-scale energy projects to home-grown food markets.

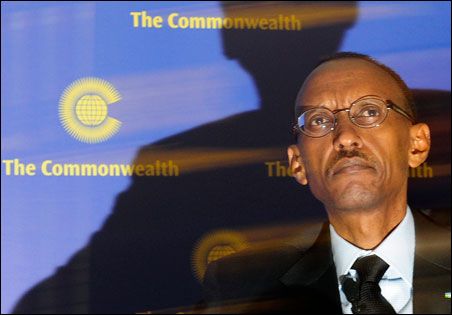

Fierce Fight Over Record of Rwandan Genocide

Search the Internet, and you'll find a wealth of sites lauding Paul Kagame as the president who led Rwanda to achieve one of Africa's most remarkable success stories.

You also will find news reports characterizing Peter Erlinder, the William Mitchell law professor, as a passionate and effective champion for the underdog and the outcast.

There is truth in both characterizations.

But there is much more to say. Erlinder's arrest in Kagame's country last week opens doors to a world of intrigue and suspicion in which the Minnesota lawyer and the former rebel leader are locked in a fierce struggle over the historical record of the Rwandan genocide.

Erlinder has been bent for years not only on implicating Kagame but also on exposing what he calls a cover-up by the U.S. Pentagon of the true story behind the genocide in which some 800,000 people were slaughtered.

For his part, Kagame — even while he took bows on international stages — was alarming the U.S. State Department with a harsh crackdown on alternate versions of what was behind his country's bloodbath.

The context for their clash is as complicated as a story can be — too complicated to report in a single news article. But Erlinder's case illustrates important parts of it.

"This case gives us a window to see what is going on in Rwanda," said Michelle Garnett McKenzie, an attorney with Advocates for Human Rights in Minneapolis who has worked to help reconcile post-war conflicts in other parts of Africa.

So let's look into the window.

Young Evangelicals

Expanding their mission

With few job openings available for graduating seniors, recruiters are an especially welcome sight on college campuses these days. When Josh Dickson, a recruiter at Teach for America, would show up at liberal-arts colleges this year, the earnest 25-year-old would hear student after student explain that their most urgent desire had always been to teach in a low-income community.

It may sound like exactly the kind of interaction that takes place on hundreds of campuses across the country. But there's something distinctive about the colleges and universities where Dickson has been doing his recruiting: they're all religious schools. And Dickson isn't your standard nonprofit recruiter. A devout Christian, he honed his persuasion techniques evangelizing to classmates as a leader of his university's chapter of Campus Crusade for Christ.

With the touch he refined telling football players they should care more about their eternal souls than the next keg party, Dickson has been seeking out student all-stars at places like Illinois's Wheaton College, long known as the Harvard of Evangelical schools. During interviews, he heard a lot of students say variations of what one Wheaton senior told him: "I just think God has given me a heart for social justice."

For many people, the word Evangelical evokes an image of fire-and-brimstone conservatism. Pat Robertson's suggestion this past winter that Haiti had brought its earthquake on itself through a Satanic pact may have been an extreme example, but it's the kind of pronouncement we've come to expect from a certain generation of Evangelical leaders.

Today's young Evangelicals cut an altogether different figure. They are socially conscious, cause-focused and controversy-averse. And they are quickly becoming a growth market for secular service organizations like Teach for America. Overall applications to Teach for America have doubled since 2007 as job prospects have dimmed for college graduates. But applications have tripled from graduates of Christian colleges and universities. Wheaton is now ranked sixth among all small schools — above traditionally granola institutions like Carleton College and Oberlin — in the number of graduates it sends to Teach for America. The typical Wheaton student, like many in the newest generation of Evangelicals, is likely to be on fire about spreading the Good News and doing good.

Two Speak for the 'Soul' of the Catholic Church

Beyond the Scandal

The Catholic Church -- the one in the hearts of its people and the dusty streets of the world, not the much-troubled, abuse-rocked Vatican hierarchy -- gets some proud and profound defense this week from two directions.

Columnist Nicholas Kristof, writing for the New York Times from the Sudan, finds priests and nuns living in the image of Jesus Christ that he says no person should dare scorn.

And Bishop Blase Cupich of Rapid City, S.D., chairman of the Committee for Child and Youth Protection for the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops has a noteworthy essay in the upcoming Jesuit weekly magazine America. He itemizes 12 lessons the U.S. bishops learned from their scathing experience with the abuse crisis -- lessons the world church could well follow.

I'll start with Kristof and two of the several people introduced in his column on finding "the great soul of the Catholic Church." He meets Michael Barton, a Catholic priest from Indianapolis, in a southern Sudan village 150 miles from any paved road where the Barton runs four schools that graduate top-scoring students.

"To keep his schools alive, he persevered through civil war, imprisonment and beatings, and a smorgasbord of disease. "It's very normal to have malaria," he said. "Intestinal parasites -- that's just normal..."

Anybody scorn him? Anybody think he's a self-righteous hypocrite? On the contrary, he would make a great pope."

Kristof moves on to the city of Juba, where he finds Sister Cathy Arata, a nun from New Jersey now working for a " terrific Catholic project called Solidarity With Southern Sudan...

"Sister Cathy and the others in the project have trained 600 schoolteachers. They are fighting hunger not with handouts but with help for villagers to improve agricultural techniques. They are also establishing a school for health workers, with a special focus on midwifery to reduce deaths in childbirth.

Religious Groups Push for Immigration Reform

When Los Angeles Cardinal Roger Mahony heard about Arizona's new immigration-enforcement law, the Catholic leader reacted with some good old-fashioned righteous anger. Taking to his blog, Mahony blasted the measure as the country's most retrogressive, mean-spirited and useless anti-immigration law, comparing it to German Nazi and Russian communist techniques that forced individuals to turn one another in.

Mahony is hardly the only religious leader outraged by Arizona's approach to immigration, which requires police to ask for papers from anyone they suspect is in the country illegally. The progressive Evangelical leader Jim Wallis has declared the state's new law a social and racial sin. The president of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society declared that by passing the law, Arizona has taken itself out of the mainstream of American life. And Mahony's Catholic colleague the bishop of Tucson has suggested that the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) join lawsuits challenging the law. (See the top 10 religion stories of 2009.)

The vigorous response to the Arizona law from faith communities is providing new energy to a national campaign for immigration reform that was already gathering steam this spring, including a massive rally in March on the National Mall. In the past week, however, Democratic leaders have sent mixed signals about their willingness to press ahead with immigration reform this year. Senate majority leader Harry Reid is backing off his vow from last week to make the issue a priority with or without GOP support. Similarly, after appearing to endorse swift action last weekend, President Barack Obama told reporters that there may not be an appetite to reform immigration laws this year. If immigration reform does fight its way to the top of the Democratic agenda, it will be largely through the efforts of a remarkably broad coalition of religious leaders.

The near universal support among religious groups for comprehensive immigration reform, including a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, is a change from the bruising fights over health reform that often saw faith leaders facing off against one another. But across theological lines, religious advocates say their traditions obligate them to care for immigrants. As the group New Evangelicals for the Common Good put it in a statement opposing the Arizona law, throughout the Bible, God commands us in no uncertain terms to show kindness and hospitality to the foreigner and the stranger. (See pictures of spiritual healing around the world.)

One Soul, Two Bodies

Friendship is a preparation for a greater love, according to Cardinal Newman, whose own relationship with his fellow priest Ambrose St John was profound, and essential to understanding his thinking.

Friendship all too often seems to have no place in Christian thought. It is regarded as a particular and selfish love, antithetical to the universal and selfless love of agape. St Augustine enjoyed a youthful friendship before he became a Christian. And yet, after his conversion, he came to look upon it with profound ambivalence: "What madness, to love a man as something more than human!" he reflected in his Confessions. Later, he developed the thought in the City of God, apparently glad when he hears of the death of a friend because the possibility that the friend will betray him, in matters of politics or affairs of the heart, has ceased.

The shadowy nature of friendship is no more forcefully conveyed than in the writings of the Christian philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, who went so far as to call it idolatrous. He argued that as friendships deepen, so too does the love of the particular over the universal, the self-interested over the selfless, the human over the divine. It’s not for nothing, Kierkegaard muses with dry wit, that the commandment is to love your neighbour.

Yet there is another strand in the tradition upon which to draw. And it can be closely associated with Cardinal John Henry Newman, a man who will be much celebrated later this year when the Pope eatifies him during the papal visit to Britain. Newman spelt out his theology of friendship in a sermon he reached on the Feast of St John the Evangelist. The evangelist and the disciple John "whom Jesus loved" are thought by many to be one and the same person.

Whether or not the evangelist John was the same individual as the disciple John is a moot point. But Newman takes the feast day as a chance to reflect on the person "whom Jesus loved". For rather than seeking to excuse the apparent particularity that description implies, Newman did the opposite. He made much of the implication that John was the "private and intimate friend" of Jesus, in marked contrast with the other disciples.

So how does this square with agape? Here is what Newman said: "There have been men before now, who have supposed Christian love was so diffusive as not to admit of concentration upon individuals; so that we ought to love all men equally … Now I shall maintain here, in opposition to such notions of Christian love, and with our Saviour’s pattern before me, that the best preparation for loving the world at large, and loving it duly and wisely, is to cultivate an intimate friendship and affection towards those who are immediately about us."

Religion and the Science of Virtue

Virtue and religion are, from a historical point of view, intimately bound up. We discard religious insights at our peril.

There is an intimate link between religion and morality. It's not fashionable to say so: many argue that talk of a link – and talk is all it is – should be stopped. After all, individuals can clearly be good without God, and religious individuals hardly stand much scrutiny as paragons of virtue. However, there's something more subtle to tease out here, and support for a connection is coming not from preachers or prelates, but science.

The source is neuroscience and evolutionary psychology. As these new sciences explore the nature of morality, they tell a story that goes something like this. Many animals, perhaps most, don't live in isolation; they co-operate. Even bacteria work together for the sake of the group. There is good reason to think that this co-operation gives rise to behaviour that can be called altruistic: it's good for others but not necessarily for the individual. The story develops further when it's observed that higher animals, like chimps or dogs, don't just behave in ways that might be called altruistic, but have social emotions too. They feel shame; they empathize; they take pleasure in pleasing others.

The implication for the human animal is that our morality is based upon an evolved set of predispositions. When we take pride, feel guilty, act honestly, show trust, we too are following social emotions that make us feel good. No doubt, this is the origin of the powerful intuition that the good life is a happy life.

Rwanda's "Miracle" of Forgiveness

A man with a machete attacks and kills your family. Repeat this scene on a genocidal scale. Would you forgive? Could you? Rwandans are, as human instinct and faith intersect in this African nation.

Kigali, Rwanda

— Rosaria Bankundiye and Saveri Nemeye are neighbors in the tiny village of Mbyo, south of Kigali. On a steamy morning, they sit in the cool living area of the clay house Saveri helped build for Rosaria just a few years ago. Two of his sons roll around on the floor while the adults talk. At one point, Saveri leans over to say something to Rosaria and she starts laughing, her smile wide. They have known each other for a long time.Nearly 16 years ago, during the genocide that wracked this African country of 10 million people for 100 days in 1994, Saveri murdered Rosaria's sister, along with her nieces and nephews. Genocidaires also attacked Rosaria, her husband and their four children with machetes and left them for dead. Only Rosaria survived. Yet when Saveri came to beg her forgiveness after he was released from prison in 2004, Rosaria considered his request and then granted it. "How can I refuse to forgive when I'm a forgiven sinner, too?" she asks.

Nearly every religion preaches the value of forgiveness. To most of us, however, such an act of mercy after so much pain seems unthinkable — maybe even unnatural. Scientists have long suspected that we are born with an instinct to seek revenge against those who hurt us. When someone like Rosaria overrides that vengeance instinct with an act of radical forgiveness, it can only be a miracle from God.

Now a growing number of researchers in the fields of evolutionary biology and psychology also believe that humans have a built-in inclination to forgive. In Rwanda, where government and church leaders are actively encouraging citizens to forgive each other, Rosaria's remarkable reconciliation with the man who killed her loved ones was not inevitable. But it is surprisingly understandable.

It is intuitively easy to grasp the instinct to enact vengeance. Michael McCullough, a psychology professor at the University of Miami, writes in his book Beyond Revenge that revenge serves several key functions for humans and other species: It deters potential aggressors and discourages those who have harmed you from repeating the offense.

But McCullough also argues that reconciliation and forgiveness are equally essential to the development and maintenance of a thriving community. If kinsmen punish a bully by casting him out of the group or by killing him, they lose both his ability to contribute to the community and their own genetic material — an evolutionary no-no. Over time, individuals and species with more conciliatory tendencies are more successful because they promote their own kin.

To Know Thyself--Genetically Speaking

Our 'genetic imperative' is a strong drive to find the biological underpinnings for all things human.

You might say that every science has its day -- or century. The 20th century, for example, is often referred to as the century of physics and chemistry. It's an appropriate moniker for the past century, since, among other things, physics and chemistry paved the way for the high-tech revolution that has forever changed our world.

It is, however, a lot more difficult to look forward and determine what science will triumph in the next 100 years. Nevertheless, even before the turn of the millennium, many intrepid prognosticators had crowned the 21st century the "century of biology." Developments over the past decade seem to be proving the soothsayers right.

Perhaps most auspiciously, researchers announced, at the very dawn of the decade, a draft mapping of all three billion base pairs in a human genome. The $3-billion Human Genome Project--that's one dollar per base pair for those keeping count--was started by the U.S. National Institutes of Health in 1990, produced a working draft of the genome in 2000 and a complete one in 2003.

The 13-year project, one of the largest scientific investigations in history, certainly seems to herald the century of biology. According to the NIH, the express aim of the project was "to provide researchers with powerful tools to understand genetic factors in human disease, paving the way for new strategies for their diagnosis, treatment and prevention." Ultimately, the project could usher in the era of personalized medicine, in which health care is tailored to each person's DNA. There is reason to believe the project is accomplishing its objectives: More than 1,800 "disease genes" have been discovered as a result of the project, and there are now more than 1,000 genetic tests that enable patients to learn about their risks for disease.

Nevertheless, it's fair to say that what we don't know far exceeds what we do know. Researchers must still learn how to "read" the map -- to understand the complex ways in which genes interact with each other and with the environment -- before the aims of the genome project are realized. This will require, among other things, the sequencing of many more genomes, which at present is prohibitively expensive.

State, Religion... and Freedom?

The debate examines if the French Model of a state without religion works. Is it possible to have a model for Society where beliefs and signs thereof are kept separate from the State?

[Professor Tariq Modood was also a guest on this program.]

France has had a legal scenario where religion is not allowed in public life since the French Revolution. This was made more concrete by a law in 1905 of the Separation of Church and State. This dilemma is most evident today in the issue of Muslim headscarves in state schools. Should France allow freedom of religious expression? Or do the principles of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity help prevent symbols of faith being hijacked by extremists?

Debate hosted by France 24’s Mark Owen.

Watch… [Video on france24.com]

Mary Karr on Becoming Catholic

Mary Karr has written two bruising memoirs—including the 1995 best-seller The Liars' Club—about her rough childhood and alcoholic parents. In Lit, her latest volume, Karr takes on the painful task of recording her own descent into addiction and depression. A lifelong agnostic, she achieved sobriety through the guidance of friends and by turning to spirituality. Karr is now a church–going, Bible–reading, Ignatian–prayer-saying Catholic, and she talked to TIME about her unlikely journey.

Did you grow up in a religious home?

My mother tried on religions the way she did husbands—she was married seven times. She did yoga back in 1962 before it was popular, she took us to the Christian Science church a few times, she read a lot about Buddhism. My father thought church was a trick on poor people. And I was a full–bore agnostic. For a long time, I didn't know people were serious about God.

So how did you form your ideas about religion? As you write about yourself in your twenties and thirties, you definitely didn't think God was anything a rational person would believe in.

I had a very Kafkaesque worldview. It was partly because of all the bleak things that happened to me and partly because of my philosophy background. I took a lot of philosophy in college. Christianity all seemed very comical to me. I remember meeting Robert Bly at a poetry workshop—he was a preacher's son—and he was talking to me about my soul. I said, "I don't have a soul. What are you talking about?"

In the book, one of the reasons you reluctantly give prayer and spirituality a try is because you see a difference between recovering alcoholics who are religious and those who aren't.

That is my experience. I know a lot of people who have been able to quit drinking and a lot of them can be pretty angry. What kept me

A Bitter Rift Divides Atheists

Last month, atheists marked Blasphemy Day at gatherings around the world, and celebrated the freedom to denigrate and insult religion.

Some offered to trade pornography for Bibles. Others de-baptized people with hair dryers. And in Washington, D.C., an art exhibit opened that shows, among other paintings, one entitled Divine Wine, where Jesus, on the cross, has blood flowing from his wound into a wine bottle.

Another, Jesus Paints His Nails, shows an effeminate Jesus after the crucifixion, applying polish to the nails that attach his hands to the cross.

"I wouldn't want this on my wall," says Stuart Jordan, an atheist who advises the evidence-based group Center for Inquiry on policy issues. The Center for Inquiry hosted the art show.

Jordan says the exhibit created a firestorm from offended believers, and he can understand why. But, he says, the controversy over this exhibit goes way beyond Blasphemy Day. It's about the future of the atheist movement — and whether to adopt the "new atheist" approach — a more aggressive, often belittling posture toward religious believers.

Some call it a schism.

"It's really a national debate among people with a secular orientation about how far do we want to go in promoting a secular society through emphasizing the 'new atheism,' " Jordan says. "And some are very much for it, and some are opposed to it on the grounds that they feel this is largely a religious country, and if it's pushed the wrong way, this is going to insult many of the religious people who should be shown respect even if we don't agree with them on all issues." Jordan believes the new approach will backfire.

A Schism?

Jordan is a volunteer at the center and therefore could speak his mind. But interviews for this story with others associated with the Washington, D.C., office were canceled — a curious development for a group that promotes free speech.

listen now or download Morning Edition

- listen… []

Why Atheism Must be Taught

Several people in comments seemed bewildered that I think you have to teach children atheism. There's a confusion here that needs clearing up. If by atheism you mean "not being a Christian" of course you don't have to teach this explicitly in modern Britain, any more than you have to teach your children not to believe in Shinto deities of ancient Egyptian ones. It's the default position of the culture.

But any worthwhile atheism is far more than not believing in some particular god. It's supposed to be a superior replacement for all religious belief. Even if it is not a doctrine, it is an attitude of mind, a way of looking at the world and of sifting evidence about it. This has to be taught.

One of the classic, if rather squirm-making examples of this process is supplied by Richard Dawkins himself, with an anecdote where his six-year-old daughter tells him that wildflowers "are there to make the world pretty and to help the bees make honey". So of course, he has to explain to her that this is an illusion, and they are really there to serve the purposes of DNA.

But even if you're not a doctrinaire atheist you have to teach children the values and skills that you treasure or else they will die. This is something common to religious and atheistic approaches to life. It would still be true even if children did not in fact have a bias towards supernatural rather than naturalistic explanations. I am sure that they do, and there's plenty of research to show the process.

In that sense, it seems to me completely incontestable that atheism has to be taught, even if the process consists largely of the transmission of attitudes and habits of mind rather than dogmatic statements.

Not to see this is an instance of a more general blindness, which Xenophanes ascribed to theologians: "The gods of the swarthy and flat nosed; the gods of the Thracians arre fair haired and blue eyed ..."

Previous Convictions

I used to be sure that Islam needed a rational reformation. Yet history has shown me that innovation and freedom have come from faith as much as reason.

Surely Islam needs a reformation? Isn’t literalism in religion an obstacle to open minds; and isn’t the promotion of rationalism the best way to boost the slow pace of science and innovation in the Islamic world? Until a few years ago, I believed that the answer to all these questions was a qualified "yes." Today I am not so sure.

This is because I’ve spent the past few years reading my way into the history of science during what is known as the golden age of Islamic civilisation. This is the 700-year period between the 8th and the 16th centuries, when the Muslim faith spread across the world and produced stunning innovations in art, architecture, crafts, medicine, science and technology.

When I began my investigations, there was one core idea that I didn’t expect to be challenged on: that blind literalism in religion is essentially a bad thing for science and for society, and that rationalism is always a force for good. Yet, as I immersed myself in the Islamic contributions to astronomy, mathematics, medicine and optics, I discovered something far more complex. Not only was a literal interpretation of religion often a positive influence on the course of science in Islamic times. More astonishingly, a policy of state-sponsored rationalism had led to much suffering, even death; and it had been largely, if unintentionally, responsible for keeping science out of Islamic colleges and universities.

Science and innovation tend to be driven by a combination of influences. These include healthcare, defence, politics, business and empire-building as well as the curiosity of the human mind. During the golden era, however, there was an additional driver: a rapidly expanding community of religious believers. Algebra, for example, was developed partly as a tool to simplify complex inheritance formulae. Similarly, spherical trigonometry and mechanical instruments such as the astrolabe were perfected because of obligations to pray daily towards Mecca. The major mosques also doubled up as observatories because they employed timekeepers whose job included having to compute accurate astronomical tables.

Mass Suffering and Why We Look the Other Way

When President-elect Barack Obama, an early opponent of the Iraq war, asked Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton -- who helped to authorize the war -- to be his secretary of state, many liberals scratched their heads.

When Obama asked Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates -- a Republican who has run the Iraq war for more than two years -- to stay on in his new administration, the scratching grew fierce.

But no one needs to read the tea leaves on one particular aspect of Obama's foreign policy: Obama, Clinton and Vice President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr. have all called for aggressive American action against humanitarian crises and genocide. Susan E. Rice, Obama's nominee for U.N. ambassador, has said that if a Rwanda-style genocide began again, she "would come down on the side of dramatic action, going down in flames if that was required." Samantha Power, a leading proponent for an interventionist American policy in humanitarian crises, was a senior Obama adviser during the presidential campaign.

"Look empirically at the kind of people who will populate the decision-making positions in the new administration and compare them with the principals" in the George W. Bush and Bill Clinton administrations, said John Prendergast, co-chairman of the Enough Project, an advocacy group that fights genocide. "What we will get, possibly for the first time in my life, is leadership from the top in these crises."

Obama might want to include a scientist named Paul Slovic in his team. Slovic, a professor at the University of Oregon, has conducted experiments that provide an unusual window into why the United States has often failed to intervene in humanitarian crises -- and why it is likely to remain slow to do so in the future.

Slovic's research suggests that the central reason the United States has not responded forcefully -- and quickly -- to crises ranging from the Holocaust to the Rwandan genocide, from the ethnic cleaning that occurred in the 1990s Balkan conflict to the present-day crisis in Sudan's Darfur region, is not that presidents are uncaring, or that Americans only value American lives, but that the human mind has been unintentionally designed to respond in perverse ways to large-scale suffering.

In a rational world, we should care twice as much about a tragedy affecting 100 people as about one affecting 50. We ought to care 80,000 times as much when a tragedy involves 4 million lives rather than 50. But Slovic has proved in experiments that this is not how the mind works.

When a tragedy claims many lives, we often care less than if a tragedy claims only a few lives. When there are many victims, we find it easier to look the other way.

Virtually by definition, the central feature of humanitarian disasters and genocide is that there are a large number of victims.

"The first life lost is very precious, but we don't react very much to the difference between 88 deaths and 87 deaths," Slovic said in an interview. "You don't feel worse about 88 than you do about 87."

We're Still Looking for Something to Believe in

A consequence of losing religion is the loss of a unifying vision of how we live -- hence the 'accommodation' debate.

We are losing the centre of gravity by virtue of which we have lived; we are lost for a while. Friedrich Nietzsche

The Will to Power (1887-88)

- - - Bruce Allen is no philosopher, but his recent radio rant does give us the opportunity to consider Nietzsche's prescient diagnosis of our multicultural malaise. As everyone now knows, Allen, the uber-talent agent and CKNW radio editorialist, recently provoked outrage with his comments about "special-interest groups." Referring to the politician-manufactured controversy about veiled women voting and to be-turbaned Sikh RCMP officers, Allen advised immigrants to "shut up and fit in." The self-described "bald-headed white guy" continued his diatribe, telling uppity immigrants that if they don't like Canada "we [bald-headed white guys?] don't need you. You have another place to go. It's called home. See ya!" Predictably, Allen's stream-of-consciousness jeremiad provoked howls of outrage from people who said they believed in freedom of speech, except for ... well, except for speech they dislike. Just as predictably, Allen's supporters charged that Allen was being denied his freedom to speak, his freedom to tell minorities that they ... well, that they shouldn't have the right to speak. So for all their rhetoric, neither of these groups really respects free speech. A pox on both their houses, I say. Now that that ugliness is over, it's time to consider what's behind Allen's words and the not inconsiderable support they've received. Prompted no doubt by the non-issue of veiled voters in the recent Quebec election, Allen was really attacking the notion of official multiculturalism, the notion that we ought to accommodate rather than assimilate other cultures. And Allen is anything but alone in his contempt for accommodation. According to an SES Research/Policy Options survey released this week, only 18 per cent of respondents said that "reasonable accommodation" of immigrants reflected their personal views, while 53 per cent thought immigrants should fully adapt to Canadian values.