Morality & Markets

Scientists of the Subprime

Can biologists avert another banking crisis?

For the past few weeks I've been talking to biologists who are advising the Bank of England on how to reform global finance, as part of a documentary for BBC Radio 4. I've been struck by the ease with which biologists have been able to step outside their research field and move confidently and assertively into another. But what exactly are they up to?

One of the causes of the financial crisis – and the haphazard international response to it – was that regulators and governments lacked the tools to understand the banking system as a whole. They knew what individual banks were doing, and they knew that these banks had myriad links to other banks, but they couldn't tell with any certainty what this meant for the banking system overall – until that is, it was much too late.

Making sense of the relationship between the individual and the system is one of science's oldest challenges. What might be new to banking is well-studied in biology, for example. This prompted Bob May, ecologist and former government chief scientific adviser, to approach the governor of the Bank of England Mervyn King with an offer of help and advice. Could there be, he wondered, any parallels between banking and ecosystems?

Drawing on their knowledge of the study of species and ecosystems, May and several others including Andrew Haldane, the Bank of England's executive director for financial security, constructed a model of the banking system. May has helped pioneer the idea that the most stable ecosystems are those with a diversity of species. Less stable ecosystems have less diversity and a higher degree of connectedness between species.

The banking model, which was published last month in the journal Nature, revealed a system that was not only relatively homogeneous – lots of banks with similar characteristics, doing the same things – but also super-connected. As with ecosystems, the model showed that such a system was also vulnerable to shocks.

This finding is likely to add weight to a view already gaining ground in the Treasury that there needs to be more diversity in banking and that the same institutions should not be allowed to act as both retail banks and investment banks – in other words, less connectivity.

The biologists also applied their knowledge from a different field – infectious disease epidemiology – to see if there are any lessons for finance. They found one that also has implications for regulators.

Church Foreclosures: Hard Times For God's Work

The Lord giveth and the bank taketh away — at least, that is what a lot of churches have found recently. Lenders foreclosed on about 100 churches last year, an enormous increase from just a few years ago. It suggests even doing God's work does not always keep the creditors away.

For Dan Burr, the road to losing his church last year began with the greatest of hopes. Twelve years ago, Burr and his wife started to worship with a few friends in their son's house in Fontana, Calif., a community about 80 miles East of Los Angeles. Neighbors began to come to the service. They brought their kids. "And it began to grow, and before we knew it we had a little viable church," Burr recalls.

Eventually Crossroads Community Church bought a building of its own — a dilapidated Boy's Club that church members fixed up themselves. Those were the glory days. Fontana was one of the fastest growing cities in the country, church attendance was booming and Burr began to make big plans.

"We were looking at [buying] vast tracks of land, building family community centers, day care and youth centers," he says, his voice brimming with enthusiasm. "We were going to really going to do this! It was great — and then BAM!"

The economic bottom fell out, and members started losing their jobs. "First, one in 10, then one in eight, then one in six of our wage earners was out of work. They just couldn't find work," Burr says.

Church offerings dropped 20 to 25 percent. The church cut staff, trimmed programs to the bone, but finally, it simply couldn't pay the mortgage. A year ago, it gave the building back to the bank. Now members are renting it until the bank finds a buyer and Crossroads is starting over. "We built up this building — just blood sweat and tears — to turn a ratty piece of land into a gorgeously landscaped thing," Burr says. "And to just walk away from it — that's hard."

listen now or download Listen to the Story: Morning Edition

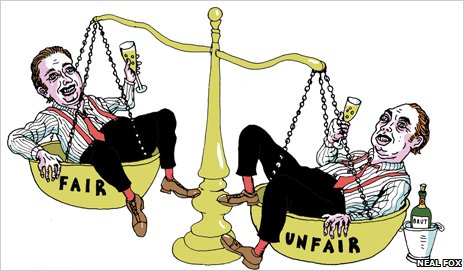

Is It Fair to Pay Bankers Big Bonuses?

It's bonus season for bankers, including at banks bailed out by taxpayers. Is this just? Great thinkers like Aristotle have mulled such questions for centuries.

Is it fair and just to pay bankers big bonuses?

You can seek an answer in three different ways, according to the three traditions of moral philosophy that dominate in our times, which are also explored in BBC Four's Justice: A Citizen's Guide to the 21st Century.

The first answer can be summed up in a word: happiness.

It's associated with the British philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who argued that if you want to know the right thing to do, ask yourself what will increase the happiness of most people, and decrease pain.

Is it the size of the bonuses paid to bankers that so riles the public? The utilitarian could stress that growth, wealth and GDP contribute much to the happiness of all. These depend upon a functioning banking system.

And banks, in turn, need investment bankers to turn a profit. If those bankers are best incentivised by the promise of large bonuses, then so be it. Indirectly, that makes everyone happier.

The utilitarian would also consider the amount of outrage and unhappiness that large bonuses generate in the population at large. There may come a point when the happiness generated by profitable banks outweighs the unhappiness of protests at the bonuses.

But then again, banks are so fundamental to our economy, and the economy is so fundamental to our happiness, that it seems unlikely this tipping point will be reached - as indeed the British government seems to have concluded.

The second tradition might come to a broadly similar view, but for different reasons.

It too can be summed up in a word - dignity - and is associated with the German philosopher Immanuel Kant.

Fixing the Economy the Scientific Way

Worried about the economy? Try investing in scientific research — it can solve problems and create jobs.

Here are two facts that might seem unrelated: 1) Most Americans cannot name a living scientist. 2) Over the last two years, by far the most pressing problems in the country have been the economy and the cost of healthcare (a chief concern of President Obama's deficit commission).

What if we told you solving the first will help us fix the second?

Without ramping up our investments in science and research — a matter barely on the public's radar in a country where 65% of the citizens can't name a living scientist and another 18% try but get it wrong — we'll be hobbled in trying to fix our long-term economic problems. That's because science creates jobs, and it can also reduce healthcare costs related to the aging of the population.

Take jobs first: This has been a theme hammered home by the National Academy of Sciences. In its two "Gathering Storm" reports released in recent years, the academy has argued strongly that our future prosperity depends on investments made now in research and innovation.

The basic premise rests on the work of Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow, who documented that advances in technology and knowledge drove U.S. economic growth in the first half of the 20th century. If it was true then, it's even more so in today's information economy.

Consider the economic reverberations of dramatically increasing the capacity of the microchip. As the academy unforgettably put it: "It enabled entrepreneurs to replace tape recorders with iPods, maps with GPS, pay phones with cellphones, two-dimensional X-rays with three-dimensional CT scans, paperbacks with electronic books, slide rules with computers, and much, much more."

It's dramatic testimony to the economic power of scientific advances. And yet over the four decades from 1964 to 2004, our government's support of science declined 60% as a portion of GDP. Meanwhile, other countries aren't holding back: China is now the world leader in investing in clean energy, which will surely be one of the industries of the future. Overall, China invested $34.6 billion in the sector in 2009; the U.S. invested $18.6 billion.

How To Fix the Billionaires' "Giving Pledge"

Show us the money--and put it to work now!

An angelic choir of media approbation has greeted Warren Buffett and Bill Gates' "Giving Pledge." The pledge they have set out to get the superrich of the nation to sign. The pledge where billionaires commit to give away the majority of their wealth to charity. Sometime. At some point, maybe after they're dead and declining stock values and greedy heirs and legatees have taken their share.

Which is why, to make the "Giving Pledge" more than a vague promise to do good, billionaires should be asked to put an audited 50 percent of their net worth on the table for charitable use now, when it can make a difference to people starving today, not later, after they've worked up a heart attack from their third wife on their fourth yacht. Look at how the Forbes list changes, how many billionaires lose their fortunes and drop off it from year to year. Gates and Buffett are right to use the Forbes list as a symbolic target, but let's get these big-talking "givers" to give now, when they've still got it.

I don't want to be too cynical about billionaires right off the bat, but there's a lot of wiggle room in that pledge. The text of the pledge obligates the pledger to give the majority of his wealth, a number that is not audited (and would obviously be minimized with taxes in mind, especially after death). In addition, the pledge just vaguely talks about giving, rather than specifying what it's most important to give money to.

How Puritans Became Capitalists

A historian traces the moment when Boston's dour preachers embraced the market.

Even in down times like these, America’s economy remains remarkably productive, by far the world’s largest. At its base is a distinctive form of market-driven capitalism that was championed and shaped in Puritan era Boston.

But the rise of Boston’s economy contains a deep contradiction: The Puritans whose ethic dominated New England hated worldly things. Market pricing was considered sinful, and church communities kept a watchful, often vengeful eye on merchants.

How could people who loathed market principles birth a modern market economy? That question captivated Mark Valeri after he read sermons by the fiery revivalist Jonathan Edwards that included detailed discussions of economic policy. Edwards turned out to be part of a progression of ministers who led their dour and frugal flocks down a road that would bring fabulous riches, and ultimately give rise to a culture seen as a symbol of material excess.

In his new book, "Heavenly Merchandize," Valeri, professor of church history at Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, finds that the American economy as we know it emerged from a series of important shifts in the relationship between the Colonies and England, fomented by church leaders in both London and early Boston. In the 1630s, religious leaders often condemned basic moneymaking practices like lending money at interest; but by the 1720s, Valeri found, church leaders themselves were lauding market economics. Valeri says the shift wasn’t a case of clergymen adapting to societal changes--he found society changed after the ministers did, sometimes even decades later.

Economic Insecurity: The Long View

Economix: Explaining the science of everyday life

Americans have climbed a historic peak of pain and uncertainty in the past decade, as the economic insecurity of the American families is greater than at any time on record.

One in five Americans, a new report for the Rockefeller Foundation found, has experienced a decline of 25 percent or more in available household income. The typical American experiencing such a plunge will require six to eight years just to climb back to previous levels of income.

Measuring the depth and breadth of the recession, and the havoc it has caused for Americans, has become a sort of cottage industry in academia and the nonprofit research world. But what sets apart this Rockefeller examination and several recent studies for other institutions — for instance, this one — is that by taking the longer view, they reveal that problems are deepening with each passing decade.

"Economic insecurity has increased over the last quarter-century," states one of the report’s co-authors, Jacob Hacker, a Yale professor. "The level of economic insecurity experienced by Americans was greater than at any time over the past quarter-century."

The report, which draws on a variety of Census and Federal Reserve data, notes that in 1985, 12.2 percent of Americans experienced an economic loss sufficient to render them economically insecure. During the recession of the early 2000s, the insecurity rose to 17 percent; today it is 25 percent.

Gallup: No Spiritual Silver Lining to Recession

"... Instead of church attendance rising when economic times get bad, as some theorize, the opposite pattern may be occurring."

Americans' self-reported church attendance is up very slightly with 43.1% of Americans reporting weekly or almost weekly attendance at a church, synagogue or mosque while their sense of economic confidence is also on the rise, according to a Gallup Survey released today.

Gallup's Economic Confidence Index" for January-May 2010 was -26, a big jump up from the depths of the recession in 2008 when it was -50 and weekly or almost weekly church attendance was 42.1% that year. This suggests that, says Gallup:" ... Such correlations do not prove causality, and it is possible that despite the more positive economic confidence, other economic realities such as unemployment could be related to the increase in church attendance.

Still, these particular population-level data do little to directly support the theory that people seek out the solace of religion, as measured in religious service participation, when economic times turn tough." Meanwhile, the biggest numbers on Gallup's charts are for those who seldom or never go to church -- holding almost rock-steady at 46% in 2008 and 45% in 2010. Of course, this speaks to public worship, not private prayer or private faith. We don't know from this survey if people are praying any more or less in tough times. And I would think if you're a praying person, there are always reasons to call on God, not just to petition for help with the mortgage.Sarkozy Wants Religious Voices Heard during Economic Crisis

RESIDENT Nicolas Sarkozy has once again praised the role of religion in society, saying that France’s main faiths must speak out at a time when economic crisis reveals a need for more ethical behaviour, and scientific progress challenges society’s moral values. Speaking at the Protestant

Institute of Theology in Paris, Mr Sarkozy said religions were "the trustees of an essential part of human wisdom".

The institute, which offers university-level theological training, transmits "part of the heritage of a civilisation we want to keep alive", he added.

Protestantism, whose followers make up about two per cent of the French population, was part of France’s national identity, he said, praising its adherents for their intellectual and ethical rigour. To underline this, he announced that a working group would study how to have the institute’s degrees officially recognised, as he has done for theology degrees from Catholic institutions of higher learning.

Since his election in 2007, Mr Sarkozy has openly praised religion several times and granted certain concessions as part of his drive to loosen the grip of laïcité, France’s strict separation of Church and State. While this always evokes protests from militant secularists, the reactions seem to be getting calmer. Under laïcité, France has traditionally refused to validate theology degrees from religious institutions because state universities do not teach the subject, leaving theology graduates without a university education in the state’s eyes.

The president seemed to be thinking of fundamentalists in all faiths when he said the Reformed and Lutheran theology taught at the Institute was a safeguard against "backward sectarian thinking" incompatible with French values and ideals. "The whole society will suffer if we leave those who feel the need to believe in the hands of those without a serious theological training anchored in a long intellectual tradition," he said. This is a point he has also made about the training of imams, which the state has promoted through a programme run by the Catholic Institute and Grand Mosque in Paris.

Massive Global Study: Money Can Buy One Form of Happiness

Money, it turns out, really can buy you happiness -- or at least one form of it, according to the biggest study to examine the relationship between income and well-being around the world.

Pulling in the big bucks makes people more likely to say they are happy with their lives overall -- whether they are young or old, male or female, or living in cities or remote villages, the survey of more than 136,000 people in 132 countries found.

But the survey also showed that a key element of what many people consider happiness -- positive feelings -- is much more strongly affected by factors other than cold, hard cash, such as feeling respected, being in control of your life and having friends and family to rely on in a pinch.

"Yes, money makes you happy -- we see the effect of income on life satisfaction is very strong and virtually ubiquitous and universal around the world," said Ed Diener, a professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Illinois who led the study. "But it makes you more satisfied than it makes you feel good. Positive feelings are less affected by money and more affected by the things people are doing day to day."

Previous studies had suggested that money was associated with happiness. But the relationship appeared weak, and earlier work tended to focus on individual countries and global evaluations of life without parsing out the effects on specific positive and negative emotions or examining differences across nations.

The new survey -- the first large international study to differentiate between overall life satisfaction and day-to-day emotions -- makes that crucial distinction, allowing researchers to explore the elusive concept of happiness in much greater nuance.

"It's sort of a new era for the study of well-being," said Daniel Kahneman, a professor emeritus of psychology and public affairs at Princeton University.

The New Poor

Decades of gains vanish for blacks

MEMPHIS -- For two decades, Tyrone Banks was one of many African-Americans who saw his economic prospects brightening in this Mississippi River city.

A single father, he worked for FedEx and also as a custodian, built a handsome brick home, had a retirement account and put his eldest daughter through college.

Then the Great Recession rolled in like a fog bank. He refinanced his mortgage at a rate that adjusted sharply upward, and afterward he lost one of his jobs. Now Mr. Banks faces bankruptcy and foreclosure.

''I'm going to tell you the deal, plain-spoken: I'm a black man from the projects and I clean toilets and mop up for a living,'' said Mr. Banks, a trim man who looks at least a decade younger than his 50 years. ''I'm proud of what I've accomplished. But my whole life is backfiring.''

Not so long ago, Memphis, a city where a majority of the residents are black, was a symbol of a South where racial history no longer tightly constrained the choices of a rising black working and middle class. Now this city epitomizes something more grim: How rising unemployment and growing foreclosures in the recession have combined to destroy black wealth and income and erase two decades of slow progress.

The median income of black homeowners in Memphis rose steadily until five or six years ago. Now it has receded to a level below that of 1990 -- and roughly half that of white Memphis homeowners, according to an analysis conducted by Queens College Sociology Department for The New York Times.

Black middle-class neighborhoods are hollowed out, with prices plummeting and homes standing vacant in places like Orange Mound, White Haven and Cordova. As job losses mount -- black unemployment here, mirroring national trends, has risen to 16.9 percent from 9 percent two years ago; it stands at 5.3 percent for whites -- many blacks speak of draining savings and retirement accounts in an effort to hold onto their homes. The overall local foreclosure rate is roughly twice the national average.

Of Money and Morality

Some of the world's leading economists and social scientists gathered at the Vatican to discuss the causes and effects of the global financial crisis, and to debate what can be done to put economics on a sound ethical footing.

In June last year, Pope Benedict XVI issued his encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, or "Charity in Truth", in which he examined the central role of charity in the Catholic Church’s social doctrine and how this must be guided by the pursuit of truth. Truth, he said, "preserves and expresses charity’s power to liberate in the ever-changing events of history", adding that without truth "there is no social conscience and responsibility, and social action ends up serving private interests and the logic of power".

In particular, Benedict focused on justice and the common good – concepts, he said, that are particularly important to the healthy functioning of our increasingly globalised society.

Analysing these themes in the light of the world’s ongoing financial and economic crisis, the Church’s Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences held a plenary meeting from 30 April to 4 May entitled, "Crisis in a global economy: replanning the journey". The academy, set up in 1994, is designed to "promote the study and progress" of the social sciences and thereby support the Church in the development of its social doctrine. It is made up of several dozen of the world’s leading social scientists, who, on this occasion, were joined by other experts in economics and finance as they gathered at the academy’s sixteenth- century headquarters in the Vatican gardens to examine the political, cultural and ethical, as well as economic, dimensions of the crisis.

Providing an insight into the causes of the crisis and discussing the potential for further upheaval was Mario Draghi, governor of the Bank of Italy and chairman of the G20’s Financial Stability Board. According to Draghi, an "ideological bias" lay behind the crisis, with financiers and regulators wrongly believing that the market, left to its own devices, would weed out bad debt. He told delegates that the global financial markets had been "stabilised" but that the underlying problems had not gone away.

In fact, said Draghi, the banking system is now in a worse position than it was before the crisis because there are still plenty of banks that are "too big to fail" but which now know, given the enormous bail-outs provided by the United States, British and other governments, that "they cannot fail".

Money, Morality, and Marriage

The Conservatives need a more radical policy on marriage to help undo the damage of their neoliberal economics.

"I hope this marriage lasts," the bride said to me as she adjusted her veil. We were just about to walk down the aisle; I was then a clergyman. "I'm still paying off the loan from my first wedding." We did a lot of them – the church being good for photos, the parish having a young demographic. But that bride's comment carried a pathos that has stayed with me.

It seemed to capture a number of the ambivalences associated with marriage today. On the one hand, the majority of people, aged between 20 and 35, say they would like to be married. The same research indicates that eight out of ten of those cohabiting want to marry too. The most common reason people give is the desire to make a commitment. Only two percent say they'd factor any tax benefits into their decision.

And yet, modern marriage is also conflicted. It's not just that it often fails, though divorce rates have steadied. Rather, the pathos in the bride's remark stemmed from her equating the financial spend on her wedding with the commitment she felt to it. She needed a further loan to make a splash for the occasion, and so not to feel half-hearted about it.

There are a bundle of neo-liberal assumptions packed into that thought, given I've read it right. There's the tendency, that's become the norm over the last 30 years, for moral value to be eclipsed by financial value. Man is no longer the measure of all things. Money is. So deep is this replacement that we now routinely make remarks such as, "I was made an offer I couldn't refuse." Cash must trump all other considerations. And inasmuch as that's true, we've ceased to live in a moral world, for morality has become a subset of economics.

It's reflected in the Tories' promise to make the UK the most family-friendly country in Europe by tax breaks and other financial means. The policy shows that the party which unleashed neo-liberalism upon us is still tied to the money-as-morality nexus. And it surely also reveals a kind of displaced guilt. Iain Duncan Smith has convinced his party that family breakdown is linked to social injustice. What the Tories can't admit is how that injustice is linked to the values of Thatcher's free-market, subsequently adopted by new Labour: individualism, short-termism, the choice doctrine, fantasies of self-sufficient freedom.

The Ethics Angle is Missing in Financial Crisis Debate

The debate about fixing the financial crisis seems to be missing a key factor -- a broad ethical discussion of what is the right and wrong thing to do in a modern economy.

The debate about fixing the financial crisis seems to be missing a key factor -- a broad ethical discussion of what is the right and wrong thing to do in a modern economy.

This omission stands out at a time when a survey by the World Economic Forum, host of the glittering annual Davos summits of the rich and powerful, says two-thirds of those queried think the crunch is also a crisis of ethics and values.

Voters in western countries may have a gut feeling that huge bonuses and bank bailouts are somehow unfair, but politicians seem unable to come up with a solid response that reflects it, according to a group trying to kickstart an ethics debate.

"People have strong emotions about right and wrong - that sense of justice is hard-wired into the way we view the world," Madeleine Bunting, one of three founders of the Citizen Ethics Network launched in London last week, told Reuters.

"Our politics have lost the capacity to connect with that kind of emotion," said Bunting, associate editor of Britain's Guardian newspaper.

"Politics has become very technocratic and managerial, all about who's going to deliver more economic growth."

The backlash against bank bail-outs has forced several chief executives of major banks to lose their bonuses this year. Despite this, the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS.L), 84 percent publicly owned, announced bonuses of 1 million pounds each to over 100 bankers last week.

U.S. President Barack Obama has proposed tighter regulations on banks but also said he didn't begrudge the $17 million bonus awarded to JPMorgan Chase & Co (JPM.N) CEO Jamie Dimon or the $9 million for Goldman Sachs Group Inc (GS.N) CEO Lloyd Blankfein because "they are very savvy businessmen" and some athletes earned more.

ENDURING VIRTUES

Perhaps not surprisingly in Britain's pre-election period, the Network -- organized by Bunting, Adam Lent of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) and writer Mark Vernon -- had no problem getting top British politicians to contribute to the debate.

We Need a Debate about Ethics in a Time of Economic Crisis

How do we decide our values? How can we do economics as if ethics matters?

One of the striking characteristics of the ongoing financial crisis and recent political scandals is that, although they have profoundly shaken our political economy, virtually no-one has broken the law. We will be living with the aftershocks of these events for years, possible decades, and there is a widespread perception that both of these systems of power have been found wanting; and yet, we seem at an almost complete loss as to know quite how to address what's happened as an issue of justice.

What's actually happened is that the ethics of individuals, businesses, institutions and government have all proved shockingly flawed or non-existent. It's that crisis of values that lies behind both events, and that we now don't appear to know how to debate, with any force. Add to that the environmental challenges we face too and it's obvious that the question of ethics in our public life is pressing. The poverty of our moral discourse raises major questions, though they are unlikely to feature significantly at the forthcoming general election, where the argument will fall back on how to decrease the deficit.

We think we need to learn how to debate ethics again. In conjunction with The Guardian, we've published a pamphlet,Citizen Ethics in a Time of Crisis, to stir up this vital element of our public life. Contributors include Philip Pullman, Michael Sandel, Jon Cruddas, Rowan Williams, Richard Reeves, Mary Midgley, Polly Toynbee, Camila Batmanghelidjh, and about 25 others. The aim of the pamphlet is to gather together a wide group of individuals - a from the left and right, secular and religious spheres, in public life and politics - who share a common concern about the ethical crisis we face.

Ethics is not just an optional extra for our political economy. Take the economic crisis. What it shows is that we don't live in the real world if we don't have an ethical sense. Instead, we live in a world of fantasy and wishful thinking - one in which economists have lost touch with the realities of material existence, making the assumption that more growth is always possible. They've also lost touch with the context in which they make decisions, as if they were not themselves morally responsible but can offload that onto free markets.

Global Economic Crisis is Also Ethical Crisis

Two-thirds of people around the world think the global economic crisis is also a crisis of ethical values that calls for more honesty, transparency and respect for others, according to a World Economic Forum poll.

Almost as many name business as the sector that should stress values more to foster a better world, said the poll for the Forum's annual Davos summit that opened on Wednesday.

Only 12.9 percent of the 130,000 people polled said businesses were primarily accountable to their shareholders. Another 18.2 percent said clients and customers, 22.9 percent named employees and 46 percent cited all of them equally.

"The poll results point to a trust deficit regarding values in the business world," the Forum said in a statement. "Only one-quarter of respondents believe that large multinational businesses apply a values-driven approach to their sectors."

The poll was conducted through Facebook in France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Israel, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey and the United States.

A large majority of 67.8 percent said the current global economic crisis was "also a crisis of ethics and values." Only 62.4 percent of younger respondents aged 18-23 agreed here but the total jumped to 78.6 percent for those over 30 years old.

The highest "yes" votes came in Mexico (80.1 percent), South Africa (77.4 percent), Indonesia (72.8 percent) and the United States (70.7 percent). France was lowest at 60.3 percent.

Only 19 percent of total responses thought faulty ethics played no role in the current economic crisis, according to the poll that can be downloaded at http//www.weforum.org/faith.

Sixty percent said businesses large and small should stress values more, compared to 23 percent for politics and 16.1 percent for global institutions.

Asked which values were most important in the global political and economic system, 39.3 percent said honesty, integrity and transparency, 23.7 percent chose respecting others, 19.9 percent said considering the impact of actions on others and 17 percent said preserving the environment.

The survey showed several variations according to countries. "Religion and faith are most likely to drive values in the United States, Saudi Arabia and South Africa," it said.

France and Germany are way ahead of others in saying firms are primarily accountable to their employees, while Israelis led both among those who said businesses were most accountable to shareholders and among those saying to clients and customers.

While two-thirds of respondents saw an ethical crisis, only 54.2 percent believed that universal values -- a possible basis for a more moral approach to business -- actually exist.

Finance Minister

Hedge fund executive and ordained clergyman Mark Hostetter weighs the morality of the financial system.

Mark Hostetter occupies an unusual perch in the financial world: he is both CEO of Vinik Asset Management, a $5 billion Boston hedge fund, and an ordained Presbyterian minister.

As an executive, he manages a firm that handles money in eye-popping quantities. As a minister, one of several associate pastors at the First Presbyterian Church of New York, he organizes seminars at New York’s Auburn Theological Seminary where CEOs discuss how they can embody personal and societal values, including secular ones, in their working lives. Hostetter, 50, walks a tricky line - we expect ministers to occupy the moral high ground, while money managers are paid to deliver profits first.

Despite anger nationally about the behavior of hedge funds and the rest of the finance industry, where a single-minded focus on high returns helped destabilize the economy, Hostetter says he rarely encounters people in his business who lack personal integrity - though he concedes that most know he’s also a minister and he may get people on their best behavior.

The system-shaking excesses of the last decade have Hostetter calling for a more moral capitalism, one in which people put the stability of the entire system above their own personal gain. He spoke with Ideas by phone from his office in Boston.

Ideas: Doesn’t the Book of Matthew say you cannot serve God and mammon?

MH: If you take traditional Christian theology, the economic system is part of God’s plan. In the parable of the talents, the servant that is rewarded is the one who utilizes that money - who isn’t scared of the money, isn’t paralyzed by it, but sees it just like anything else, as a tool to be utilized in promoting whatever God’s goals are in the particular context. There may be a preference for the poor

The Economics of Mistrust

The current crisis might not sink us financially. But when the dust settles, how will our sense of humanity have fared?

Just how serious is the economic state we're in? At a debate on Christian responses to the recession, Andrew Dilnot, the well-respected economic commentator and evangelical Christian, suggests the crisis isn't so bad. Recessions are part of life in a capitalist economy: the real question is why there hasn't been a recession for the last 16 years, since in previous decades recessions have come every 3 or 4. He also thinks that the worry about the levels of debt the UK is now carrying is a worry about the wrong thing. Debt is basically a good thing, at the macroeconomic level: it is the key that liberates people from poverty. Ask yourself how one billion children have been lifted out of poverty in Asia. It couldn't have been done without the alchemy of debt, the ability of the countries concerned to borrow and lend. As for UK's debt, it's larger than it was, but it is still pretty modest by historic standards.

So why the sense of panic? Dilnot's suggestion is that it's a moral issue. He believes that there is a kind guilt lying behind much of the current anxiety about economic woes. We, in the UK, are a rich generation – four times as rich as our parents and grandparents were after the second war. So we need to get used to our prosperity, and not let the media drive us into paroxysms of fear, which actually make things worse since they stop us enjoying the benefits of wealth.

Dilnot is at pains to point out that we are a massively redistributive economy too: 1% of earners at the top of the pile pay 25% of all income tax; the bottom 20% of earners are 60% better off because of the welfare benefits taxation funds. This redistribution he interprets as a practical application of the commandment to love your neighbour. Humans have a tendency to greed. But Christians should be proud of their economy, even celebrate it as a manifestation of Christian faith.

That was the pollyannarish view. But his opponent was John Milbank, the well-respected theologian. When he stood up to speak, he lambasted the analysis.

The big issue is not the ups and downs of the economic cycle, but it is the kind of people we are becoming because of late capitalism. Whilst we are richer, that wealth has been bought at the price of massive social disruption, which is corrosive of civic virtues like trust. Further, the world has become a different place because, now, banks are bigger than governments. This means that governments are arguably more beholden to the markets than to the people – which is to say our system might be described as a market oligarchy. Sound excessive? Well, consider that as a result of the banking crisis, a few rich "lords" have been bailed out at the expense of the masses of poor "serfs", in possibly the biggest redistribution of wealth in history – and a redistribution in exactly the opposite direction to that celebrated by Dilnot.

Satan and Economic Growth

We continue exploring the relationship between religious beliefs and economies. We just heard about possible links between the prosperity gospel and risky behaviors that led to the housing bubble and subsequent crash. Now, we ask whether belief in eternal damnation might help economies grow.

Education, access to technology, the rule of law and trade policy all influence economies. But a pair of Harvard researchers has sifted through 40 years worth of data from dozens of countries, and conclude that religious beliefs have a measurable effect on developing economies – especially the fear of hell.

For more we’re joined by Michael Fitzgerald. He wrote about this topic for The Boston Globe Ideas Section. He researched the article while a Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Fellow.

- listen… [7 minutes, mp3 format]

Satan, the Great Motivator

The curious economic effects of religion

What makes economies grow? It’s a question that has occupied thinkers for centuries. Most of us would tick off things like education levels, openness to trade, natural resources, and political systems.

Here’s one you might not have considered: hell.

A pair of Harvard researchers recently examined 40 years of data from dozens of countries, trying to sort out the economic impact of religious beliefs or practices. They found that religion has a measurable effect on developing economies - and the most powerful influence relates to how strongly people believe in hell.

That hell could matter to economic growth might seem surprising, since you can’t prove it exists, let alone quantify it. It stands as one of the more intriguing findings in a growing body of recent research exploring how religion might influence the wealth and prosperity of societies. In recent years, Italian economists have presented findings that religion can boost GDP by increasing trust within a society; researchers in the United States showed that religion reduces corruption and increases respect for law in ways that boost overall economic growth. A number of researchers have documented how merchants used religious backgrounds to establish one another’s reliability.

The notion that religion influences economies has a long history, but the specifics have been vexingly difficult to pin down. Today, as researchers start to answer the question more definitively with the tools of modern economics, what’s emerging is a clearer picture of

Rowan's Vision for Development

Can giving to the poor be seen not simply as alleviating the suffering of others, but about receiving a gift in return?

Rowan Williams has called for a broadening of the development agenda, so that secular agencies working in developing countries might become more fluent in the language of faith. Conversely, he stressed, faith-based communities must be more open to the imperatives of the "development establishment." Learning from each other would not only be good for development. It might make possible the "distribution of dignity", alongside the establishment of rights, he said.

The Archbishop of Canterbury has a remarkable ability to highlight key issues of our day, issues that many then recognise, even though they don't share his faith commitment. He has done so again with his analysis of the work of development. It came at the culmination of a series of RSA-sponsored lectures entitled New Perspectives on Faith and Development. (He also achieved what must be a rare eclecticism for public talks, commending to his audience both a papal encyclical by Benedict XVI and a volume written by George Monbiot.)

Williams's analysis is premised on the observation that there has been, and remains, a longstanding unease between the development establishment and faith communities. The development establishment is often wary of the way faith communities operate, believing they undermine the universal ethic that inspires development. So, the fear is that faith communities may prefer to care for their own, not for all. Or they may hinder the spread of human rights, particularly to women. Or they may use development as a cover for proselytising.

Conversely, religious communities are often suspicious of the secular agenda of development agencies, feeling they ride roughshod over deeply held convictions and patterns of life, and impose an essentially foreign view of the good life, imported from the materialistic culture of the rich west.

Williams is clearly on the side of faith in this debate. But he is not seeking to score points. Rather, he points to what might be gained should both sides transcend their prejudices. That would be nothing less than a renewed vision for development.

Religious Stock and the Belief Crunch

Buy Buddhism, sell Anglicanism? Be careful, because, just as in financial markets, shocks and bubbles can test your faith.

Faith markets are perhaps like financial markets. After all, religions have become global: opinions and beliefs are traded every day in the world's cosmopolitan cities, much like stocks and shares. Faith markets might even have their own kind of securities, as people hedge against overpricing in their main faith holding by buying into the practices of a different philosophy – the Christian who reads the astrology columns, the Buddhist who interprets meditation through neuroscience.

Moreover, theologians appear to hold to the faith equivalent of the efficient market hypothesis. They tend to assume that their beliefs can withstand the external shocks of encountering other traditions, and further, that the eternal truth will out – perhaps as economists have believed that markets tend towards equilibrium.

Then again, that last point could be wrong. Rather like the economists who failed to foresee the credit crunch, sociologists failed to see that secularisation would not destroy faith but rather reinvigorate it. So perhaps we can refine the analogy by borrowing some of the insights put forward by George Soros, that master of markets. He might help us better understand today's faith markets.

Soros proposes two key doctrines. First, that market prices always distort the underlying fundamentals, his doctrine of fallibility. Second, that this mispricing itself affects reality, his doctrine of reflexivity. Take the doctrine of fallibility. You might feel that Anglicanism has the best assets, at least in the UK, what with its glorious cathedrals and seats in the House of Lords. What fallibility warns is that such pricing does not necessarily make it a stock with a future. Add in the doctrine of reflexivity, though, and the picture changes again, for it may be the case that those assets themselves convince the market that Anglicanism is, in fact, worth investing in. It all depends upon cultural feedback mechanisms and whether the owners of the assets can leverage them to their greatest advantage – whilst watching that they don't become over-leveraged, of course, and so precipitate a faith crunch.

Chicago Schooled

The visible hand of the recession has revitalized critics of the Chicago School of Economics.

On a sunny day this spring, more than 1,000 people streamed into the Sheraton near the Gleacher Center for a conference on the Future of Markets. Its keynote panel, headlined by Nobel laureate Gary S. Becker, AM’53, PhD’55, featured six Chicago economists with differing viewpoints. The stock market was in the early part of a rally that would yield its best quarter since 1998. Stock-market turnarounds usually signal better times coming, but in an economy contracting 6 percent, better was relative.

So the rally didn’t change the feeling among the free-market enthusiasts at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business management conference that market economics was on shaky ground: most of the financial industry, they felt, had been nationalized in all but name. Two of the three U.S. automakers looked like they would follow suit. The government was capping pay in the financial services. What in the name of the Chicago School was going on?

The central idea of the Chicago School of Economics

holds that economies work best when markets operate freely, with limited government participation. The Chicago School, a phrase coined in the 1950s, championed an old idea: 1870s neoclassical economics. Yet in the wake of the Great Depression and World War II, it was a radical proposition. It went against the ideas of John Maynard Keynes, who believed government should play an important role across an economy. At the time, the U.S. government was viewed with reverence, as the force that beat the Depression, won World War II, and was girding to rebuild Europe. Keynesianism held "a virtual monopoly," says James J. Heckman, the Henry Schultz distinguished service professor of economics and 2000 winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. "People thought markets couldn’t work, incentives weren’t important."The Chicago School took almost the opposite tack, expressing near disdain for government. Some of that disdain was echoed during May’s Future of Markets keynote panel by Kevin Murphy, PhD’86, who holds an endowed chair named for 1982 Nobel laureate George J. Stigler, PhD’38, a pillar of the Chicago School, along with Milton Friedman, AM’33. Wearing his habitual baseball cap despite the suits and ties all round him, Murphy ticked off the challenges facing the nation. When he got to the problem of remaking General Motors, he paused. "Who in their right mind would put the government in charge of that task?" Titters came from the audience, then applause.

Another crowd might have booed—say, at Columbia University, current home of economist Joseph Stiglitz, who won the 2001 Nobel Prize for work on how markets misfire. Stiglitz threw this bomb via a Bloomberg News article last winter: "The Chicago School bears the blame for providing a seeming intellectual foundation for the idea that markets are self-adjusting and the best role for government is to do nothing."

In his 2003 book The Roaring Nineties, Stiglitz recounts how, in the four-year period between 1997 to 2001, private companies and capital markets invested $65 billion into building telecom networks. They lost $61 billion of it. The episode is his version of Murphy’s question above: "Who in their right mind would put markets in charge of that task?"

Salon commentator Andrew Leonard also called out the Chicago School, writing in an April 29 column, "The direction in economic thought pioneered by Milton Friedman and enthusiastically adopted by Ronald Reagan and his Republican successors helped to get us where we are today—in the worst economic contraction in 50 years, characterized by an increasing concentration of wealth in the top tiers of society."

Sumo Wrestlers Are Big

But are they a Big Question?

Friedrich Hayek’s 1944 book The Road to Serfdom, with its sweeping theme that any form of collective government leads to tyranny, laid the groundwork for the Chicago School of Economics. Will another book lead to its unraveling?

Freakonomics, the 2005 book by Chicago economist Steven Levitt and journalist Stephen Dubner, uses economic techniques to study questions nontraditional in the world of economics, such as whether Japanese sumo wrestlers cheat and whether legalizing abortion led to less crime. The book has sold 3 million copies, inspiring lots of talk about economics and a regular New York Times blog by the authors. But it also brought out critics, including from within Chicago’s economics department. The New Republic’s Noam Scheiber took aim at the Freakonomics phenomenon in his April 2007 article "Freaks and Geeks: How Freakonomics is Ruining the Dismal Science."

Heavily quoted in the piece: Chicago Nobel laureate James J. Heckman.

Heckman doesn’t cite Levitt by name, but he does complain about a trend that finds economists going after only small, manageable questions and discouraging them from pursuing problems they can’t solve quickly or easily, such as the nature of business cycles. Scheiber connects the dots for those who didn’t get it: "Heckman’s allusion to a certain pedagogical technique is almost surely a shot at his Chicago colleague, Steve Levitt."

Heckman has nothing against Levitt, he says in an interview. "What I’m concerned about is not him personally; he’s fine." But he disdains Levitt’s approach: "Freakonomics is an exercise in triviality. It’s intellectual escapism. It substitutes cuteness for substance. And the style of research that suggests that you need to somehow produce a paper every two months that’s cute and catches the eyes of the New Yorker reader damages the kind of long-term research that economists do and still do at Chicago."

The Everlasting Message Of Reverend Ike

Frederick J. Eikerenkoetter, was born in Ridgeland, S.C., to a Dutch Indonesian father and African-American mother. He became pastor of his father's Baptist church at age 14. But eventually he moved to a more charismatic faith — one that which focused on faith healing — and he traded the doctrines of sin and suffering for a philosophy of abundance. He became known as Reverend Ike.

"He was part revivalist, part evangelist, part Johnny Mathis, if you will," says Jonathan Walton, an assistant professor of religion at the University of California at Riverside, who has written about Eikenerenkoetter.

"He would often say these lines such as, 'You know, I come to you today lookin' good, feelin' good and smellin' good.' And this would just kind of ooze off of him. And this charisma just attracted persons from many different ranges of society."

In the 1970s, Reverend Ike's sermons drew hundreds to his Palace Cathedral, a renovated movie theater in New York's Washington Heights. He reached millions more through radio and TV with this message, and started a newspaper and a magazine. He was one of the first to advocate what is now known as the "prosperity Gospel." The idea is that God wants each of us to be spiritually and materially abundant.

At one of his sermons at a Madison Square Garden, for example, he told the packed crowd: "If you can honestly think and feel that you are worthy or deserve a million dollars, that million dollars must come to you!"

"His message is quintessentially American, right?" says Professor Walton. "It's this kind of God is on your side, if you can see it, if you can believe it, you can claim it. And God wants this for you."

And Reverend Ike's own success was Exhibit A. He owned multiple homes and more than two dozen cars, including a few Rolls-Royces. He had many critics, who claimed he was preying on the poor. He faced several lawsuits and government investigations into his ministries. Other Christian leaders derided his theology as shallow and misguided.

Initially, Carlton Pearson, interim senior pastor at Christ Universal Temple, says he was once one of them.

"People would testify, 'I came here in my raggedy car and I'm drivin' away with a Cadillac!' But we just felt it was what we call carnal, unspiritual, that he was talking to the flesh and speaking to the ego and all that kind of thing."

But if leaders didn't like Reverend Ike, his congregants — largely middle- and working-class blacks — did. When others, like the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., talked of sacrifice and social reform, Reverend Ike spoke of material empowerment.

"I say there no virtue in poverty," he would preach. "There is no honor in poverty! There is no style in poverty! Poverty doesn't have any class!"

listen now or download All Things Considered

- listen… []

Marx's Challenge

Marx saw religion as a comforter. But the real challenge is to live without the 'heart in a heartless world' that it provides.

Karl Marx was a serious atheist. He didn't think that religion was mad or particularly bad: it was "the opium of the people" but "the heart in a heartless world" too. Instead, he had a theory about the nature of religion that attempted to penetrate to the heart of the human condition.

For Marx, the human animal is fulfilled in its labouring. We are made from the earth – we are "of nature", as he wrote in his early Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. So, when tilling the soil, we connect to the stuff of which we are made, reshaping it, and thereby shaping ourselves. Therein lies our satisfaction. We find ourselves through our labour in fields – even in gardens, that bourgeois mode of self-realisation.

However, those acts of self-realisation are increasingly thwarted in organised society. When people learn to cooperate, a struggle ensues because we become disconnected from the products of our labour. The ever-more complex modes of production manifest in capitalism lead to the deepest sense of alienation. We lose touch with the land, though can't give up on the expectation that work will fulfil us, even when it abuses and empties us.

As a result, human individuals seek consolation. Perhaps one of the reasons that going for a picnic is such a joy in the summer is that eating sandwiches on the earth reconnects us with that of which we are made. Picnicking involves taking our food to the fields – back to the fields, you might say. It symbolically reforms the link between our alienated selves and our nature-loving labouring selves. Therein lies its pleasure, at least as Marx might have had it.

Poverty, Biology, and Intelligence

Why do poor kids have more trouble in school? Is it due to environment or biology?

Why do poor kids have more trouble in school? Is it due to environment or biology? The answer, according to a new study, may be both.

We tend to think of biological explanations as an alternative to environmental explanations. The clearest example of this conflict is the debate over genetic theories of intelligence. But biology is more than genetics. It includes physical processes that are environmentally influenced. So if poverty causes cognitive impairment, biology should be able to explain part of the effect.

That's what a study published last week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences tries to do. Working with a sample of nearly 200 children, the authors set out to identify "underlying biological mechanisms that may account for the income-achievement gap." But instead of looking for genes, they look for a different kind of mechanism: measurable stress.

Research Links Poor Kids' Stress, Brain Impairment

Children raised in poverty suffer many ill effects: They often have health problems and tend to struggle in school, which can create a cycle of poverty across generations. Now, research is providing what could be crucial clues to explain how childhood poverty translates into dimmer chances of success: Chronic stress from growing up poor appears to have a direct impact on the brain, leaving children with impairment in at least one key area -- working memory.

"There's been lots of evidence that low-income families are under tremendous amounts of stress, and we know that stress has many implications," said Gary W. Evans, a professor of human ecology at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., who led the research. "What this data raises is the possibility that it's also related to cognitive development."

With the economic crisis threatening to plunge more children into poverty, other researchers said the work offers insight into how poverty affects long-term achievement and underscores the potential ramifications of chronic stress early in life.

"This is a significant advance," said Bruce S. McEwen, who heads the laboratory of neuroendocrinology at Rockefeller University in New York. "It's part of a growing pattern of understanding how early life experiences can have an influence on the brain and the body."

Previous research into the possible causes of the achievement gap between poor and well-off children has focused on genetic factors that influence intelligence, on environmental exposure to toxins such as lead, and on the idea that disadvantaged children tend to grow up with less intellectual stimulation.

"People have hypothesized both genetic and environmental factors play a role in why poor children don't do as well in school," said Martha Farah, director of the center for cognitive neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania. "Experiential factors can include things like having fewer trips to museums, having fewer toys, having parents who don't have as much time or energy to engage with them intellectually -- to read to them or talk to them." But Evans, who has been gathering detailed data about 195 children from households above and below the poverty line for 14 years, decided to examine whether chronic stress might also be playing a role.

How Innovations from Developing Nations Trickle-Up to the West

A funny thing has happened on the way to globalization: Innovation now trickles up from emerging to advanced economies. And it may be the way of the future.

We know how innovation works. We get iPhones; those less fortunate overseas get whatever we dropped in the recycling bin on our way out of the Apple Store. We get Gore-Tex; they get 2007 New England Patriots 19-0 T-shirts. We get the Wii; they play rock-paper-scissors. We get collateralized-debt obligations ... well, we can't win them all.

Innovation has always been about people in rich nations getting the latest stuff and the rest of the world getting our castoffs as our markets scale and prices come down. So why is Nokia [0] looking to use Kenya to debut a free classifieds service (think a mobile-phone version of Craigslist), complete with a first-ever feature that lets people shop using voice commands to browse for goods? And why are Western banks seeking ideas from India's ICICI when its average deposits are one-tenth of those in the West?

The answer is that the traditional model of developing new products is quietly reversing course. Call it "trickle-up innovation," where ideas take shape in developing markets first, then work their way back to the West. "If it's radically innovative and reduces costs, it's going to get looked at and will accelerate," says Michael Chui, the consultant doing heavy lifting on a McKinsey Technology Initiative report on this subject that includes more than 100 PowerPoint slides crammed with examples. As the credit crunch forces frugality on companies everywhere, it should turbocharge the shift toward developing markets.

The Faithful Come Out

China is experiencing a religious resurgence and, remarkably, the government is letting it happen.

If you walk down Battery Path in central Hong Kong you are likely to see a silent protest on one side of the pavement. Two or three demonstrators sit, cross-legged on the ground, in meditation. Next to them, on boards, are displayed the hideous images of individuals who have been beaten and presumably tortured. Passing parents shield the eyes of their children.

These are supporters of Falun Gong, the religious movement founded in the 1990s. It is distinguished by being probably the highest profile victim of the Chinese government's fear of organised religion. A clampdown began after a peaceful protest in July 1999 in Tiananmen Square when Falun Gong was outlawed. According to Amnesty International, the government then launched "a long-term campaign of intimidation and persecution, directed by a special organisation called the 610 Office." Protests are allowed in Hong Kong, just yards away from government offices, because of the status of the Special Administrative Region.

It is a clear reminder of the dark side of the Chinese authority's approach to religion. However, it is not the whole story.

Martin Palmer is the secretary-general of the Alliance of Religions and Conservation (ARC). He runs one of the few organisations that have a license from the Chinese government to work with religious groups in the country. He can hardly stress enough how profound the changes now taking place are. So are they a sign of a more relaxed attitude towards freedom of religious expression?

About three years ago, he was approached to make contact with Taoists. This followed similar suggestions about working with Buddhists, three years before that. These invitations struck Palmer as odd, to say the least. After all, this is a regime that had tried to wipe out Taoism, destroying about 98% of its temples, statues and scriptures.

However, reforms have continued apace. Just last year, in 2008, several public holidays were reformed, again indicative of development. The May Day holiday, symbolic for any socialist, was downgraded and in its place two others were revived. One is the Qing Ming, or Festival of the Dead, on which Chinese people remember their ancestors. A second is the Dragon Boat Festival, which partly commemorates a famous mandarin who warned an emperor against corruption. The significance of that story will not be lost on the Chinese people.

How to End Poverty

The third section of Creating a World Without Poverty details Muhammad Yunus' vision for creating social businesses and how they will eliminate poverty.

Yunus recaps some of the hoops that had to be jumped through before Grameen Danone could start making high-nutrition, low-cost yogurt in Bangladesh. Capital markets and regulators aren't set up to finance social businesses or to tax them (or exempt them from taxes, as may be the case), and Group Danone had to do yeoman's work with shareholders and regulators, including creating a social mutual fund that did not promise to maximize returns first and foremost. His goal is to expand market capitalism by making the unconventional conventional, working in an idea for a Social Dow Jones Index, Social MBAs and other ideas for increasing the visibility – and viability — of such businesses.

He also has high expectations for turning information technology as an engine for eliminating poverty. His experiences in Bangladesh suggest that the digital divide is not inevitable, and where it exists it does not need to be permanent. He cites the One Laptop Per Child and Intel Classmate PC projects as examples, and throws out a few other ideas that he hopes someone will pursue.

Yunus' vision will either inspire or irritate, because it is an outsized vision – a world with no poverty, a capitalism that doesn't weigh only profits – that stands outside today's reality. It will make many business people uncomfortable, and many others disdainful. By the end of the book, when he discusses the consumer society and whether it can and should be sustained, and says not in its current form, he will be preaching to a choir, and also to converts.

Yunus: Capitalism is Half-Baked

In "Creating a World Without Poverty," Muhammad Yunus has written a dangerous book. Not so much for his goal – that's merely outlandish, since most people expect the poor will always be. Besides, Yunus knows how to make audacious ideas real – he created Grameen Bank to bring financial services to the poor, and proved that microfinance can be profitable and powerful. Doing so earned Yunus and Grameen the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize (arguably it should have been the Economics Prize).

What's dangerous are his questions. Like, if capitalism is so effective, why must 60 percent of the world's population squeak by on six percent of its income? Why is it that China's remarkable economic growth is ruining its environment? Why is poverty on the rise in the United States, even as its overall wealth skyrockets?

These questions skewer conventional economic wisdom that our current model of capitalism is the be-all and end-all for global economics. Yunus dares to say that market capitalism is both underdeveloped and, in its current form, bad for most of us. He echoes J.A. Hobson, the early 20th century critic of capitalism whose 1902 book Imperialism skewered British capitalists, accusing them of being economic parasites. (He also echoes Adam Smith himself, who wrote in the Wealth of Nations about inequities in the system that reduced competition and the flow of labor). Yunus is not so vituperative as Hobson, but he does call out business leaders, saying bluntly that "capitalism is a half-developed structure" and that modern economics is guilty of

…assuming that people are one-dimensional beings concerned only with the pursuit of maximum profit…. We've created a one-dimensional human being to play the role of business leader, the so-called entrepreneur. We've insulated him from the rest of life, the religious, emotional, political and social. He is dedicated to one mission only – maximize profit. He is supported by other one-dimensional human beings who give him their investment money to achieve that mission. To quote Oscar Wilde, they know the price of everything and the value of nothing.Yunus believes that governments, nonprofit organizations, international organizations like the World Bank and attempts at corporate social responsibility all have failed to address the problems of modern free-market capitalism.

Does the free market corrode morality?

Tough question, right? The Templeton Foundation, best known for massively funding research and programming in the realms of science and religion, took this on as one of its topics in a series of publications and forums on the "Big Questions" in modern times.

Three leading economic and philosophical intellectuals held a seminar today in London (I watched on webcast) to address, "Does the free market corrode moral character?"'

Gary Rosen of the Templeton Foundation began by reminding the audience that the foundation founder, the late Sir John Templeton, once said, "Through risk and challenge we grow both in worldly wisdom and spiritual strength."

Unfortunately, I'm not so far grown in wisdom yet. Much of the discussion went over my head. Even so, it was clear that there are rousing arguments among the global intelligentsia over markets and morality.

"All humanly acceptable economic systems are morally corrosive to some extent," said John Gray, an emeritus professor at the London School of Economics and author of False Dawn: The Delusions of Global Capitalism.

Gray argued that the modern version of the American free market died "from hubris and greed that promoted snatching wealth from pyramids of debt."

Jagdish Bhagwati, a professor of economics and law at Columbia University, added "ignorance" to black marks on the free market. He said the new financial instruments, such as derivatives packaging "toxic" mortgages, went beyond the knowledge of the central bankers. They took the brakes off regulation without ever understanding that this might become "a dagger at our throat," he said.

Can Community Gardens Save a City?

In Holyoke, urban agriculture is spurring development and improving nutrition.

Daniel Ross walks through a garden in South Holyoke with plants straight out of Puerto Rico, chicharos and jabaneros. This was the first of what are now 10 jardines comunitarios -- community gardens -- located throughout low-income neighborhoods in the area, and it sits about a half block from the blighted Main Street shopping district, a place where vacant buildings and overgrown lots seem to outnumber functioning businesses. "Hey, Carmelo," he calls to a man working a plot in midmorning. It's Carmelo Ortiz, a retiree who emigrated from Puerto Rico to Holyoke decades ago and helped found this garden back in 1991, working with local volunteers to reclaim a lot made vacant when a church burned down.

These seemingly humble gardens are part of a local success story with national significance. They've blossomed because of the nonprofit agency Nuestras Raices -- Our Roots -- which has received numerous honors for its model of using urban agriculture to spur economic development, enrich a community through cultural pride, and improve nutrition for youth and the community in general.

The gardens are cooperatively maintained but are overseen by Nuestras Raices, which helps people get access to the lots. The gardeners use the food for their own households, share it with neighbors, or sell it at farmers' markets.

The nonprofit also has a 30-acre farm site where it teaches people who were farmers in Puerto Rico or other countries how to be commercial farmers in Massachusetts.

Financial Hardship and the Happiness Paradox

The United States is awash in gloom. Overwhelming majorities of Americans say they are dissatisfied with the country's economic direction, and the intensity of unhappiness is greater than it has been in 15 years, according to a recent Washington Post-ABC News poll. The answer, pundits, politicians and policy wonks agree, is to find a way to quickly return to economic growth.

The unstated assumption is that growth will lift the gloom and, in the long run, make America happier. If that's true, then it ought to follow that America should be much happier today than it was a generation ago -- it is much wealthier.

The question of whether the country is happier today than it was in, say, 1970 turns out to have a surprisingly good empirical answer. For nearly four decades, researchers have regularly asked a large sample of Americans a simple question: "Taken all together, how would you say things are these days -- would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy or not too happy?"

The results are sobering. Even before the current economic downturn, the United States, on average, was less happy than it was in 1970, even though it is vastly richer.

Economist Richard A. Easterlin at the University of Southern California was among the first to notice the paradoxical disconnect between a nation's economic growth and the growth of its happiness. The "Easterlin Paradox" was once thought to be limited to rich,

“Pro-Life” Drugstores Market Beliefs

No Contraceptives for Chantilly Shop

When DMC Pharmacy opens this summer on Route 50 in Chantilly, the shelves will be stocked with allergy remedies, pain relievers, antiseptic ointments and almost everything else sold in any drugstore. But anyone who wants condoms, birth control pills or the Plan B emergency contraceptive will be turned away.

That’s because the drugstore, located in a typical shopping plaza featuring a Ruby Tuesday, a Papa John’s and a Kmart, will be a "pro-life pharmacy"—meaning, among other things, that it will eschew all contraceptives.

The pharmacy is one of a small but growing number of drugstores around the country that have become the latest front in a conflict pitting patients’ rights against those of health-care workers who assert a "right of conscience" to refuse to provide care or products that they find objectionable.

"The United States was founded on the idea that people act on their conscience—that they have a sense of right and wrong and do what they think is right and moral," said Tom Brejcha, president and chief counsel at the Thomas More Society, a Chicago public-interest law firm that is defending a pharmacist who was fined and reprimanded for refusing to fill prescriptions for birth control pills. "Every pharmacist has the right to do the same thing," Brejcha said.

But critics say the stores could create dangerous obstacles for women seeking legal, safe and widely used birth control methods.

"I’m very, very troubled by this," said Marcia Greenberger of the National Women’s Law Center, a Washington advocacy group. "Contraception is essential for women’s health. A pharmacy like this is walling off an essential part of health care. That could endanger women’s health."

The pharmacies are emerging at a time when a variety of health-care workers are refusing to perform medical procedures they find objectionable. Fertility doctors have refused to inseminate gay women. Ambulance drivers have refused to transport patients for abortions. Anesthesiologists have refused to assist in sterilizations.

The Gospel of Money

Megachurch pastors and broadcast ministries are drawing renewed scrutiny for living lavishly off the faithful's funds. Fortunately, a divide is emerging in the world of evangelicals: the 'haves' and the 'will have none of it.'

The love of money," the New Testament teaches in I Timothy 6:10, "is the root of all evil." But what about some televangelists' fondness for major bling — such as multiple, multimillion dollar estates, luxury cars, vacation homes, exotic trips and private jets? Does that make them, in the words of one author, "pimps in the pulpit?"

Many outside the evangelical movement are puzzled by the apparent lack of outrage following reports of high-living, tax-exempt religious broadcasters. Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, has been looking into six megachurch pastors and broadcast ministries, requesting financial records. Richard Roberts has stepped down as president of Oral Roberts University following charges that he used the school's resources for family perks, such as a trip to the Bahamas for his daughter.

These charges come as no surprise to those within the evangelical world. Such tales of excess and profligacy have been an open secret for years.

Some justify this way of life by arguing that, as advocates of the "prosperity gospel," it only follows that those who are the most faithful will prosper — in a big way. Is this why there has been no outcry among the faithful? Perhaps it is a reflexive circling of the wagons.

"Within conservative media ministries, criticism from outsiders often is seen as a badge of honor that validates a ministry's righteousness," says Quentin Schultze, of Michigan's Calvin College, author of Christianity and the Mass Media in America.

But there is something new going on. Just as political, ideological and generational fissures are emerging among the nation's evangelical leadership, there is also one involving lifestyle.

In one camp are those being scrutinized by Grassley: Benny Hinn of Texas, a flamboyant faith healer whose followers believe he can raise the dead; Paula White, a motivational speaker whose recent divorce from her co-pastor husband rocked their Tampa megachurch; and Joyce Meyer, a St. Louis author and speaker whose broadcasts are heard in 200 countries. They make no apologies for the way they spend their salaries, speaking fees, CD and book royalties and "love offerings," lavish gifts of cash and jewelry.

What makes this discussion delicate and sometimes uncomfortable — especially among evangelicals — is that many of these leaders come from the Pentecostal (or Charismatic) tradition. This brings with it undercurrents of class and culture. Historically, those once derided by other Christians as "holy rollers" for their ecstatic prayer and preaching have their roots in the working and lower-middle class, in rural areas and small towns. There is the implication that their leaders, having grown up in hardscrabble circumstances, tend to have a nouveau riche weakness for flashy displays of wealth.

Capital Ideas and Social Goals

SINCE 2001, Lee Zimmerman's Evergreen Lodge has helped almost 60 low-income young adults get their lives on track, while consistently paying 9 percent back to investors backing his business. Pura Vida Coffee, of which John Sage was a co-founder in 1997, has generated $2.7 million in cash and resources for health and education programs for children and their families.

Both companies deserve praise for their good deeds. But what might be more remarkable about the founders of Pura Vida and Evergreen Lodge is the way they raised capital to build businesses that have two bottom lines: one financial and one social.

Such business models are becoming increasingly popular among philanthropists and foundations, which like the idea of self-sustaining charities. They also want their investments to have the same kind of social impact as their donations, an idea called mission-related, or program-related, investing. A study released earlier this year by FSG Social Impact Advisors, a consultancy founded by Michael E. Porter, a Harvard Business School professor, and Mark Kramer, a former venture capitalist, calculated that mission-related investing has grown by 16.2 percent a year over the last five years.