Related Topics

As This Blog Closes, Religion Stories Live On

Now might be a great time to talk about the afterlife.

After four years of spirited conversation, news and adventures from Cambridge, England, to little Barack Obama's school in Indonesia, Faith & Reason and its accompanying reader-led Faith & Reason Forum are shutting down.

USA TODAY is celebrating 30 years with a massive redesign of all publishing platforms.

First, the important thing that's not changing: I still cover religion -- the best beat on the print/Web/smartphones/tablets-you know-what-I-mean. Many great stories lie ahead.

However, how and where you find my work -- and top wire stories and the best of Gannett's religion correspondents such as Bob Smietana at The Tennessean -- will change.

Several digital subject-area pages, including the online religion page, will vanish as stories are mainstreamed into News. If you read on a smartphone or tablet, you won't notice any change. But if you read religion coverage at USATODAY.com on your laptop, these stories will be running in News, Nation and Politics, just as they already do in print.

So this is not good-bye. It's more of a change-of-address notice.

You can find my stories with a Google alert on my byline (don't forget that pesky Lynn in the middle) or as my friend on Facebook. I'll soon surface with a new Twitter handle as well. You can also e-mail me at cgrossman@usatoday with your ideas and thoughts.

Don't I sound chipper? Well, sure, I'm a little sad. This has been exhausting, glorious fun !

Readers by the thousands chimed in on controversial posts here. Remember Sarah Palin's invention of "death panels" or the atheist "Woodstock" -- the Reason Rally on the National Mall?

Masters of Men and Machines

Leonardo da Vinci's only documented stay in Rome, from 1513 to 1516, was not one of his happier or more productive periods. By contrast with his preceding stints in Milan, where he enjoyed unquestioned pre-eminence and produced the great paintings currently on view at London's National Gallery, Leonardo's time at the papal court was marked by competition from younger artists. First among these rivals for patronage stood Michelangelo, who one year earlier had finished his frescoes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling and would go on to adorn Rome with several other masterpieces, including the dome of St. Peter's Basilica, which now ranks second only to the Colosseum as an icon of the Eternal City.

So it's fitting that a new exhibition of drawings by Leonardo and Michelangelo at Rome's Capitoline Museum—part of an architectural complex designed by Michelangelo himself—should show the latter artist to greater advantage.

Michelangelo's part of this show includes studies for some of his greatest paintings, vivid anatomical drawings and one exquisitely finished work.

Leonardo is represented here for the most part by sketches and geometrical diagrams, some of them minuscule, often interspersed with mathematical calculations or extensive notes in the author's distinctive mirror handwriting. As records of Leonardo's restless and overflowing mind at work, these pages from his notebooks are of undeniable interest, though many of those on display here call for more scrutiny and background explanation than practical in a gallery setting.

Of course, any chance to see rarely exhibited drawings by either Leonardo or Michelangelo is worth taking, and seeing their works together only enhances our appreciation of both artists. This show's catalog notes that it was organized with a "mirror-like" format, designed to facilitate comparison.

It is hardly obvious, at first, just how much the selections from each oeuvre have in common. The highlights of the exhibition, which features 66 works in total, are nine by each artist grouped under the generic category of "masterpieces." All but one of the Michelangelo drawings in this section are of the human figure. Leonardo's, on the other hand, are mostly of machines.

Exiled Libyan Jews Look with Hope

ROME — The Jews of old wandered the wilderness for 40 years before entering the Promised Land. For the exiled Jews of Libya, it’s already been 44.

The struggle to reopen a synagogue in Libya, 44 years after the forced departure of the country’s last Jews, is emerging as a high-profile test of the new Libyan government’s commitment to freedom in the post-Moammar Gadhafi era. On Sunday (Oct. 2), David Gerbi, a Libyan Jew who immigrated to Rome in 1967 at age 12, used a sledgehammer to enter the closed Dar Bishi synagogue in Tripoli. Two Muslim clerics lent their support, and some neighborhood residents offered help with cleanup.

But when Gerbi returned on Monday, he found the door locked and was told to stay away or risk losing his life. "If they want to prove that it’s different from Gadhafi ... they need to do the opposite," a tearful Gerbi told reporters after being turned away.

Meanwhile in Rome, leaders in the Italian-Libyan Jewish exile community watch such developments with a mix of apprehension and cautious optimism. Post-Gadhafi Libya, they hope, might ultimately prove itself more tolerant and just than the land they left.

The Jewish presence in Libya dates back more than 2,000 years; at the end of World War II, the country’s Jewish population still numbered more than 40,000. But their environment grew increasing inhospitable over the following two decades, with outbreaks of anti-Semitic violence linked to conflicts between the new State of Israel and its Muslim-majority neighbors.

Libyan Jews began to emigrate, most of them to Israel; by 1967 there were only about 6,000 Jews left in the country, almost all of them in the capital city of Tripoli. After Israel won the Six-Day War against Egypt, Jordan and Syria in June 1967, the reaction in Tripoli finally made the Jews’ situation intolerable.

Remembering 9/11

From Longwood Medical Area

Ten years ago today I was working at an educational institute based at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. My boss, Dr. J.B. McGee, had developed a prototype for a Virtual Patient program, one that third and fourth year Harvard Medical students could utilize (on CD-ROM) to learn some of the details of patient care that they would not be able to pick up on rounds.

In a Managed Care world, patients were not in the hospital long enough for students and interns to get a comprehensive view of a particular disease or condition. J.B.’s program was designed to help fill that void.

My job: I was one of the QuickTime guys; shooting and editing the video to embed in the program interface, developed using Macromedia Director and its custom code: Lingo. How clumsy it all seems now. Flash has long since displaced it.

J.B. had a cable TV in his office, and we gathered that Tuesday morning, some of us just in from the Green Line with our morning coffee, when he came down the hall to tell everyone that a plane had crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

Like most people, we thought it was some kind of horrible accident; and I remember listening to the voice-over commentary on CNN, even as the second plane appeared in the distant background shot of the live video of the smoking North Tower.

What I recall most vividly, though, at the end of that day (or perhaps it was the next): being home after work with my ten-month old daughter. She was just learning to walk. On CNN, they were carrying footage of the Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace.

The military band struck up the U.S. National Anthem in solidarity. Hundreds of English men and women gathered at the gates, many with tears in their eyes.

When my little daughter saw my composure break, she stared at me for a few seconds before bursting into tears.

Flashback to 2001

Taliban with a small 't' dream of Afghan jihad after 9/11

Right after 9/11, Reuters editors asked correspondents with experience in Afghanistan and Pakistan if they wanted to go back there to report. Within days, I flew from Paris to Islamabad, a city I’d left 15 years earlier. Soon, I set up a temporary bureau in Peshawar for several weeks of reporting from there. Among my trips outside of Peshawar was one to Chitral, a mountain town to the north that was close to the Afghan border. One morning, I visited the local mosque and sat down with the teenaged boys gathered in a corner to avoid the disapproving gaze of the imam giving Koran recitation lessons in the main hall. After I introduced myself in Urdu as a journalist from New York, all they wanted to talk about was 9/11. My story is repeated here to show the confused mix of reactions I found.

CHITRAL, Pakistan, Oct 3, 2001 (Reuters) – It was a hot, lazy morning at the Jamia mosque in Chitral, high in Pakistan’s mountainous north, and the teenage boys here to learn the Koran were talking more about Afghanistan than about Allah.

"The Americans will attack Afghanistan and all Muslims will go to fight against them," Mohammad Karim, a sharp-eyed boy with a whispy beard, declared with a certain bravado. "Yes, jihad (holy war)!" others sitting in the circle chimed in, pointing to the Afghan border only 60 km (40 miles) to the west. "Amreeka murdabad! (death to America!)," they murmured. Then something their Koran training never prepared them for happened. An American reporter sat down with them and began asking each one if he really was ready to go fight.

"I’m ready," one piped up, adjusting his prayer cap. "Me, too," another said, grinning. Boys sitting in other circles with teachers stole furtive glances over to the discussion, but then buried their faces back in the Koran. When his turn came, Attaullah hesitated before blurting out, "It’s dangerous there. I don’t want a war. Islam is a peace-loving religion." Slowly, others backpedalled too, despite the efforts of an older boy named Saidullah to end this talk with the infidel and herd the students back to their Koran readings.

"Stop talking to that American!" he shouted in the local Khowar dialect, rather than the Urdu they were speaking. "Doesn’t he know the Jews did it? The Jews destroyed the World Trade Center to get America to start a war against Islam." The youngest boys, maybe about 10 or so, watched in fascination, even if they could not follow the whole discussion in Urdu, Pakistan’s national language. One waif nibbled absentmindedly at a corner of his Koran as he listened to the bigger boys talk war.

These are taliban (Koran students) with a small "t" – poor Muslim boys whiling away their days at the madrassa (religious school) at the local mosque like millions of others around Pakistan who have no other school to go to. Pakistani madrassas have earned a bad name abroad ever since the Afghan Taliban, a movement of fire-and-brimstone fundamentalists, transformed seemingly overnight from studying at hardline Koran schools at refugee camps in this country to seizing power in Kabul in 1996. Their draconian rule, including barring females from work and school and destroying unique Buddhist art from the pre-Islamic past, made them world pariahs even before September 11.

Why Vanishing Sharks Deserve Attention, and Even Affection

One of nature’s oldest, most successful and least visible predators is in profound trouble.

As Juliet Eilperin reports in her dismaying new book, "Demon Fish," more than 73 million sharks are killed each year by fishermen who hack off their fins to sell as a coveted ingredient for soup. As many as 90 percent of sharks in the world’s open oceans have disappeared.

Sharks reveal much about the ocean, how it functions and why it is now in peril. As so-called top predators (like lions, tigers and polar bears), they help keep the marine ecosystem in balance through efficient hunting and killing.

So when they are eliminated, cascades of ecological interactions are disrupted. Food webs (who eats whom) unravel. Diseases emerge. Jellyfish populations explode. By slaughtering sharks, we degrade the sea itself. Ms. Eilperin, an environmental reporter for The Washington Post, spent two years traveling the globe looking for sharks and people who worship, loathe, hunt, exploit or study them. She takes us to Papua New Guinea, where "shark callers" lure the animals from the depths and catch them by hand, using snares. She interviews shark fin dealers in Hong Kong and commercial fishermen in Florida who entice customers with the question "Are you man enough to catch a shark?"

She swims in shark-infested reefs, once lowering herself into the water inside a shark cage, and visits a South African beach where spotters blow sirens when great white sharks come close to shore. Over all, she explains why sharks, so often reviled and feared, deserve our attention and, as she argues convincingly, our affection.

"Demon Fish" reveals the close relationship between humans and sharks through the interplay of history and culture, with China as protagonist. The power of shark fin soup to convey status cannot be overstated. The dish is central to middle-class weddings and banquets, where it is a symbol of a family’s good reputation.

Anders Breivik is not Christian but anti-Islam

Norwegian terrorist Anders Breivik's ideology is fuelled by a loathing of Muslims and 'Marxists', his writing spurred by conspiracy theories.

The Norwegian mass murderer Anders Behring Breivik, who shot dead more than 90 young socialists at their summer camp on Friday after mounting a huge bomb attack on the centre of Oslo, has been described as a fundamentalist Christian. Yet he published enough of his thoughts on the internet to make it clear that even in his saner moments his ideology had nothing to do with Christianity but was based on an atavistic horror of Muslims and a loathing of "Marxists", by which he meant anyone to the left of Genghis Khan.

Two huge conspiracy theories form the gearboxes of his writing. The first is that Islam threatens the survival of Europe through what he calls "demographic Jihad". Through a combination of uncontrolled immigration and uncontrolled breeding, the Muslims, who cannot live at peace with their neighbours, are conquering Europe.

But these ideas, however crazy, are part of a widespread paranoid ideology that links the European and American far right and even elements of mainstream conservatism in Britain.

In an argument on the rightwing Norwegian site Dokument.no, Breivik wrote: "Show me a country where Muslims have lived at peace with non-Muslims without waging Jihad against the Kaffir (dhimmitude, systematic slaughter, or demographic warfare)? Can you please give me ONE single example where Muslims have been successfully assimilated? How many thousands of Europeans must die, how many hundreds of thousands of European women must be raped, millions robbed and bullied before you realise that multiculturalism and Islam cannot work?"

He obsessively posted statistics showing the growth of Muslim populations in Lebanon, Kosovo, Kashmir and even Turkey over the centuries in order to demonstrate the same process was under way in Oslo right now, as well as in other European cities.

The second is the idea that the elite have sold out to "Marxism", which controls the universities, the mainstream media, and almost all the political parties, and is bent on the destruction of western civilisation. "Europe lost the cold war as early as 1950, at the moment when we allowed Marxists/anti-nationalists to operate freely, without keeping them out of jobs where they could seize power and influence, especially teaching in schools and universities," he wrote.

These two grand conspiracies are linked by the "Eurabia" conspiracy theory, which holds that EU bureaucrats have struck a secret deal to hand over Europe to Islam in exchange for oil.

Arabs in London

When the world arrives at London's 2012 Olympics site, one of the first buildings visitors will see is the Aquatics Centre - a beautiful structure designed by one of London's most illustrious Arab citizens. Zaha Hadid, born in Baghdad, is renowned as the greatest architect to emerge from the Middle East since the Ottoman mosque builder Sinan - and is adept at building bridges that are both physical and metaphorical.

Hadid's canvas is global. Residents of Abu Dhabi using the new Sheikh Zayed Bridge can see her remarkable design skills every day, and she is behind the performing arts centre being built on Saadiyat Island. But she is also one of the architects of a deeper bridge of understanding between Arab nations and the rest of the world. Hadid is one of more than 300,000 Arabs who live in London, with more than half a million across the UK. Numbers are boosted in the summer months by up to a million and a half visitors from the Middle East, mainly the Gulf. For many, the city's cosmopolitan appeal is the magnet.

"London is fantastic. There is nowhere like it in the world," says Sulayman Al Bassam, a British-Kuwaiti theatre director and playwright. "It is everything and anything to anyone." Al Bassam, whose trilogy of plays inspired by Shakespeare is nearing completion, has lived and worked in the UK for almost two decades. His production of Richard III was the first Arabic-language production staged by the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Building cultural bridges is at the heart of Shubbak - the name means "window" in Arabic - the capital's first celebration of contemporary Arab culture. The three-week festival is showcasing the work of more than 100 creative figures at 30 venues across the city. "Shubbak is an opportunity to see the world through new eyes and to strengthen the relations between artists working in London and across the Arab world," says London's mayor, Boris Johnson. "It also celebrates the influence of London's significant Arab population in our city today and demonstrates the importance of London as a capital of international cultural exchange."

Karima Al-Shomely is an Emirati artist in London for Shubbak. "I love being here," she says. "Back home in Sharjah in the summer, it is too hot to go outdoors much. Here you can walk in the streets, all over the place, and enjoy things."

She is working with Khalid Mezaia, a graphic artist and illustrator from Dubai, on a project called Shopopolis that engages with the staff at Westfield, London's largest shopping mall. Mezaia says: "In Dubai the art scene is really young and anyone can be an artist. But in London there is a long tradition." Arabs have been visiting Britain for centuries; Phoenicians and other ancestors of Arabs came as traders before the Roman invasion. But the first significant Arab community was established when Yemeni seamen settled in London's docklands.

The flow was two-way. Westerners had made forays into the Arab world since the dawn of Islam. One of the first was an Anglo-Saxon pilgrim named Willibald who died in 787 after spending several years in the Middle East.

Medieval religious writing abounds with references to Saracens and Arabs, but the first notable Arab character in English literature was Othello in William Shakespeare's tragedy. The playwright is believed to have been inspired after joining crowds thronging London's streets to witness a delegation from Morocco led by Abd El-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun to the Court of Queen Elizabeth I.

Yale's New Jewish Quota

The university's shameful decision to kill its anti-Semitism institute

To many observers, both inside and outside Yale, killing the program seemed a shockingly ill-considered act. Even supporters of the move, such as Yale's Rabbi James Ponet, conceded (in an email to me) that it was "foolishly" executed. And considering Yale's well-known anti-Semitic past—the university long had a "Jewish quota," allowing in only a limited number of Jewish students per year, that it abandoned only in the 1960s—the decision is a shameful one.

Yale cited several reasons for killing YIISA, a program devoted to the cross-cultural examination of anti-Semitism that had been in operation since 2006. But many observers suspect the turning point was a YIISA conference last August called "Global Anti-Semitism: A Crisis of Modernity" which, while featuring 108 speakers from five continents, dared acknowledge the existence of anti-Semitism in some Islamic cultures. There has been talk—though no proof—of fear of offending potentially lucrative donors from the Middle East. Charles Small, the director of YIISA, "blamed radical Islamic and extreme left wing bloggers for the bad publicity," according to the Yale Daily News, which also reported that Small "pointed out that it was the largest conference on antisemitism ever, and it would have been absurd for the conference to ignore Muslim antisemitism."

It is worth noting that discussing the existence of anti-Semitism in some Islamic cultures does not imply there is anything essentially anti-Semitic about Islam. Small denied emphatically to me that any such Islamophobia was evident in the conference or in YIISA's seminars. But while the backlash against YIISA's conference included predictable protests from the official PLO representative and the group's supporters in America, the more subtle—and yet ludicrous—objection to YIISA's conference and YIISA's work came—as Ben Cohen pointed out in the Forward—in the charge of "advocacy," leveled by some YIISA opponents on campus. The charge that the program exhibited too much "advocacy" against anti-Semitism, as opposed to academic analysis of anti-Semitism. It seems unlikely that Yale tells its cancer researchers not to engage in advocacy against the malignancies they study, doesn't it?

I should note before I defend YIISA further that I have spoken both at YIISA, and at Yale's Hillel-like Slifka Center (which, shamefully, in my view, failed to defend YIISA), and I also edited a 700-page anthology on the question of contemporary anti-Semitism, Those Who Forget the Past. Finally, I should add that I had a highly positive experience as a student Yale, with no noticeable exposure to anti-Semitism.

As for the integrity of the work the center was supporting, consider, for example, this list of YIISA seminars examining anti-Semitism from a comparative perspective. It gives you a sense of the cosmopolitan range of its cross-cultural studies of the prejudice.

Apparently, I'm not alone in finding the center's work worthwhile. Closing YIISA generated a backlash. In the face of scathing articles in the New York Post by Abby Wisse Schachter (the daughter, incidentally, of Harvard's Ruth Wisse, one of the world's leading Jewish-literature scholars) and in the Washington Post by professor Walter Reich (he wrote, "Yale just killed the country's best institute for the study of anti-Semitism"), Yale had a PR problem.

Sharia and the Scare Stories

The arguments about Islam put forward by Michael Nazir-Ali make it difficult to take him seriously.

I was at Hammicks bookshop in London's Fleet Street on Wednesday to hear Michael Nazir-Ali launch a book on sharia law, Sharia in the West. I don't think I will ever be able to take him as seriously again. Politically, of course, his project is entirely serious. It's part of an attempt to take over Christianity in this country. For some rightwing Anglicans, Nazir-Ali is the shadow Archbishop of Canterbury. He has moved out of the official Anglican communion and aligned himself decisively with the conservatives evangelicals of Gafcon, which last week launched its latest attempt to disrupt the Church of England, the "Anglican Mission in England". Charles Raven, one of the leaders of that project, was at the Nazir-Ali book launch, too.

Gafcon is normally defined in the media by its campaigns against homosexuality but its members hate much more than that. Reform, the movement's branch in England, is also fundamentally opposed to women priests, and internationally they take a strongly anti-Muslim line.

The rich and influential Nigerian Gafcon church sees itself fighting a cold jihad across the centre of the country. Nazir-Ali, who comes from a convert family in Pakistan, has always been hostile to, and suspicious of Islam but in recent years he has increasingly come to talk of it the way that rightwing Americans used to talk about global communism.

I have myself argued in favour of Caroline Cox's bill to make plain the limits of sharia law in this country. Sharia can reinforce injustice and some parts of it codify some loathsome attitudes. But sharia arbitration operates by consent; and it will wither in this country if that consent is withdrawn. Talking about Muslims as if they were an alien species makes this far less likely to happen. And that is how many people were talking last night.

Nazir-Ali kept talking as if sharia law were an ineluctible consequence of Islam: he spoke of developments in Iran and Pakistan as if Tower Hamlets were next.

Another of the animating spirits of the book, the "radical orthodox" theologian John Milbank broke with him in the discussion. "My essays in the book are not at all pro-Islamic," he said, "but I think I am slightly less extreme than the bishop, and I find myself wanting myself not to have this case overstated."

Islamophobia and Antisemitism

There is some violent prejudice against Muslims in Britain today. But is there a more subtle insistence that they're really foreign

The great thing about being in Dubai last week (where I was for a British Council conference on religion and modernity) was being a foreigner once more. It's how I spent much of my childhood, how I grew up, and how I feel most at home; but it brings professional rewards as well as personal pleasures. I was for the first time in my conscious life in an environment where the most important thing about Muslims was not that they were Muslims. It gave me a moment of sudden awareness, like waking in a log cabin without electricity when all the background hum and tension of electric motors that you never normally hear is suddenly audible by its absence.

The people I was hanging out, and sometimes drinking, with were Muslim intellectuals whom I know and like in England. They're not in any way discriminated against in this country, as far as I can tell: their lives are not impeded by the kind of people who think that Muslims are a problem to be solved. The kind of crude and open prejudice that flourishes online – and go and look at comments on the Telegraph website, or the videos of Pat Condell, if you want to know what I mean – is very rare in liberal circles, and when we catch ourselves at it, we feel guilty.

But there is a more subtle and general sort of prejudice which holds that Condell is not an extremist outcast. Richard Dawkins, for example, has praised Condell, and used to sell his videos on his website, which reminds of the way that Oswald Mosley remained a member in good standing of the English upper classes until the outbreak of the second world war, despite his views on Jews. What I realised in Dubai was that in England today Muslims can't escape being Muslims, any more than Jews in England in the 20s or 30s could escape being Jewish. They can't just be unremarkable, as Jews in England can be now.

In Dubai, or neighbouring Sharjah, being a Muslim did not matter in the same way. Obviously, people made a huge amount of fuss about Islam. But when you're in a room full of Muslim academics and students arguing about culture, or censorship, or why there is so little science in the Arab world, the arguments themselves make one thing wholly plain. Neither side is more Muslim than the other. None of the flaws of the Islamic world are essential or intrinsic to it. They may be widespread, and in some cases quite horrible. But they're all cultural and not just religious.

China Vows To Ordain Bishops Without Vatican's OK

(RNS) In a move likely to aggravate tensions with the Vatican, China's state-run Catholic church announced on Thursday (June 23) that it may soon ordain more than 40 bishops without the approval of Pope Benedict XVI.

According to the official Xinhua news agency, a spokesman for the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association (CPCA) said the church "faces an urgent task" of choosing bishops for more than 40 dioceses, and planned to do so "without delay."

For more than half a century, China's 12 million to 15 million Catholics have been divided between the state-run CPCA and an "underground" church of Catholics loyal to the pope.

In recent years, the Vatican and Beijing have tacitly agreed on a number of bishops acceptable to both sides. But last November, Joseph Guo Jincai was ordained the bishop of Chengde without papal approval, an event the Vatican called a "sad episode."

Another such ordination, in the diocese of Hankow, was scheduled for early June, but was unexpectedly postponed at the last minute.

Earlier this month, the Vatican reiterated that bishops who consecrate other bishops without a papal mandate incur automatic excommunication, as do the men they consecrate and all other ministers who participate in the ceremony.

At the same time, the Vatican's statement allowed for "mitigating circumstances," under which the penalty of excommunication does not apply, specifically if any of the parties was "coerced by grave fear ... or grave inconvenience" to participate.

Carl Jung, Part 4: Do Archetypes Exist?

Jung's theory of structuring principles remains controversial--but provides a language to talk about shared experience

Jung took the inner life seriously. He believed that dreams are not just a random jumble of associations or repressed wish fulfilments. They can contain truths for the individual concerned. They need interpreting, but when understood aright, they offer a kind of commentary on life that often acts as a form of compensation to what the individual consciously takes to be the case. A dream Jung had in 1909 provides a case in point.

He was in a beautifully furnished house. It struck him that this fine abode was his own and he remarked, "Not bad!" Oddly, though, he had not explored the lower floor and so he descended the staircase to see. As he went down, the house got older and darker, becoming medieval on the ground floor. Checking the stone slabs beneath his feet, he found a metal ring, and pulled. More stairs led to a cave cut into the bedrock. Pots and bones lay scattered in the dirt. And then he saw two ancient human skulls, and awoke.

Jung interpreted the dream as affirming his emerging model of the psyche. The upper floor represents the conscious personality, the ground floor is the personal unconscious, and the deeper level is the collective unconscious – the primitive, shared aspect of psychic life. It contains what he came to call archetypes, the feature we shall turn to now. They are fundamental to Jung's psychology. Archetypes can be thought of simply as structuring principles. For example, falling in love is archetypal for human beings. Everyone does it, at least once, and although the pattern is common, each time it feels new and inimitable.

Young Somali Immigrant Appreciates Life

PELICAN RAPIDS, Minn. — Abdirashid Nuur was lucky he arrived in Minnesota during the month of August. He had enough adjustments confronting him without the daunting distraction of a Northern Minnesota winter.

Abdi (as his friends call him) had boarded a plane in Kenya's Nairobi – a sprawling metropolis of more than 3 million people. It's a subtropical city teeming to the pulse of hip-hop and Benga music, where glittering malls and gritty street hustlers operate side by side, thousands fill the stands for major league soccer and the cops never seem to get ahead of the robbers. His destination was Pelican Rapids, a two-stoplight town of 2,500 people where farm fields roll right up to the commercial district. The culture throbs here, too, but with a far different rhythm and flavor, reflecting civic interests of Northern European immigrant settlers: quilt shows, library projects, festivals in the parks and high school sports. The police department's website lists seven officers on the force.

"I couldn't believe this was such a small city," Abdi said.

This is where we live

It was not the America he had seen in movies, which typically were set in New York, Washington, D.C., or Los Angeles. But it was the place where a brother had landed when he made it to the United States ahead of the rest of the family. "My brother said, 'This is where we are going to live for the rest of our lives,' " Abdi recalled.

One of the first "American" foods Abdi tasted was pizza. What else? "I didn't like it," he said.

But that was nearly four years ago. Now, he has acquired a taste for pizza – and, more profoundly, an appreciation for peaceful Pelican Rapids. "I live freely, here," he said. "Life is much better. ... I like small cities. There is less trouble."

From Mogadishu to uffda

His then-now comparisons reach beyond Nairobi to Somalia, where Abdi was born in Mogadishu, the capital city, and spent the first year of his life. His family fled the violence of that failed state and lived in refugee camps in Kenya before making it to Nairobi.

Abdi had learned English in the refugee camps. But it was British English spoken with a Somali accent, and he initially struggled to make himself understood in Minnesota. "I could understand what people were saying, but they could not determine what I was saying," he said.

That has changed in four years so that he sounds very much like other Minnesotans. Indeed, he's learned the word uffda – although he doesn't use it on a regular basis. "I always heard people saying that word," he said. "I think it is from Norwegian or something." What stood out about Abdi during our interview was not his accent. It was his politeness and formality. He wore a crisp dress shirt and a tie to our interview at the Lutheran Social Services Refugee Center. His dark eyes focused intensely while I asked questions, and he carefully thought through his answers before uttering a word.

The Sharia Myth Sweeps America

If you are not vitally concerned about the possibility of radical Muslims infiltrating the U.S. government and establishing a Taliban-style theocracy, then you are not a candidate for the GOP presidential nomination. In addition to talking about tax policy and Afghanistan, Republican candidates have also felt the need to speak out against the menace of "sharia."

Former Pennsylvania senator Rick Santorum refers to sharia as "an existential threat" to the United States. Pizza magnate Herman Cain declared in March that he would not appoint a Muslim to a Cabinet position or judgeship because "there is this attempt to gradually ease sharia law and the Muslim faith into our government. It does not belong in our government."

The generally measured campaign of former Minnesota governor Tim Pawlenty leapt into panic mode over reports that during his governorship, a Minnesota agency had created a sharia-compliant mortgage program to help Muslim homebuyers. "As soon as Gov. Pawlenty became aware of the issue," spokesman Alex Conant assured reporters, "he personally ordered it shut down."

Former House speaker Newt Gingrich has been perhaps the most focused on the sharia threat. "We should have a federal law that says under no circumstances in any jurisdiction in the United States will sharia be used," Gingrich announced at last fall's Values Voters Summit. He also called for the removal of Supreme Court justices (a lifetime appointment) if they disagreed.

Gingrich's call for a federal law banning sharia has gone unheeded so far. But at the local level, nearly two dozen states have introduced or passed laws in the past two years to ban the use of sharia in court cases.

Despite all of the activity to monitor and restrict sharia, however, there remains a great deal of confusion about what it actually is. It's worth taking a look at some facts to understand why an Islamic code has become such a watchword in the 2012 presidential campaign.

What is sharia?

More than a specific set of laws, sharia is a process through which Muslim scholars and jurists determine God's will and moral guidance as they apply to every aspect of a Muslim's life. They study the Quran, as well as the conduct and sayings of the Prophet Mohammed, and sometimes try to arrive at consensus about Islamic law. But different jurists can arrive at very different interpretations of sharia, and it has changed over the centuries.

Importantly, unlike the U.S. Constitution or the Ten Commandments, there is no one document that outlines universally agreed upon sharia.

U.S. Muslims React: Relief, But Not For All

Muslims in the U.S. reacted quickly, and with relief, Monday to the news that Osama bin Laden had been killed. But some wondered if it will really ease tensions that many Muslims feel from their neighbors.

On the streets of Dearborn, Mich., Muslims were reveling in the death of the al-Qaida leader.

Muslims in the U.S. reacted quickly, and with relief, Monday to the news that Osama bin Laden had been killed. But some wondered if it will really ease tensions that many Muslims feel from their neighbors.

On the streets of Dearborn, Mich., Muslims were reveling in the death of the al-Qaida leader. "This guy should have been dead a long time ago," says Hassain Yami. "Hopefully the rest them will be dead soon."

"He did not give Muslims a good name, so I think it's definitely a victory for us," says Channah Ali, adding that bin Laden distorted the Muslim faith.

Muhammad Cheab says he hopes that now Americans will see Muslims in a new light. "We're good American citizens," he says. "We pay our taxes and live like everyone else does and we're proud to live here." Cheab hopes bin Laden's death will take the heat off Muslims here. Feisal Abdul Rauf, the imam who stepped into controversy by trying to locate a mosque near ground zero, believes it will do just that.

"I think that this is a turning point," he says. "There's still an enormous amount of work to be done. But there's no doubt, in the American perception this has helped a lot to bring closure."

It's hard to find an American Muslim leader who has criticized the American military action. Some clerics abroad say burying bin Laden at sea violated Muslim laws and was aimed at humiliating Muslims. But not Nihad Awad, executive director of the Council on American Islamic Relations. "The most important issue is that this terrorist has been eliminated," he said at a press conference. "And Muslims do not care about the details of how he was buried."

listen now or download Listen to the Story: All Things Considered

Muslim World Had Soured on Bin Laden since 9/11

hough large swaths of the Muslim world cheered Osama bin Laden after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, there has been relatively little sympathy expressed for him from those quarters since his killing Sunday - a testament to the dramatic falloff in global Muslim support for the al Qaeda leader in the last decade.

While the spontaneous street celebrations that broke out in American cities like New York and Washington over the news of bin Laden’s killing by U.S. Special Forces have not been repeated in the Muslim world, there has been praise for his death from some Muslim political leaders.

In Yemen, which has been racked by unrest in recent months as hundreds of thousands have demanded the removal of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, bin Laden’s killing has yielded a rare moment of political unity, with both Saleh’s government and the opposition praising the development. Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Salam Fayyad, meanwhile, hailed the killing as a "mega-landmark event." Certain quarters of the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt’s newly emboldened opposition party, have also voiced support, even as the party released a statement opposing assassinations of any kind and asking the U.S. to "stop intervening in the affairs of Muslim and Arab nations."

And while many other leaders from the Muslim world have so far been mum on bin Laden’s death, virtually none have voiced overt criticism of the U.S.-led operation. Experts say that’s largely because even Muslims in the Middle East, Asia and elsewhere who were once supportive of bin Laden soured on him years ago.

Middle East Beacon

Saudi Arabia is advancing, led by a reformer king and many hopeful women.

With the popular revolts of the Arab Spring showing no sign of abating, rattled Saudi authorities have disbursed new multibillion-dollar incentives directly to their citizens as a prophylactic strategy. It’s not clear that they need to. Such panic-button tactics undermine decades of work by the Saudi government that is little seen by the outside world. Saudi authorities would do well to regain a perspective best expressed by their own even-keeled citizens.

Dr. Summayah Chabra, my former Saudi colleague, a vascular surgeon and mother of three, believes revolt in Saudi Arabia unlikely, putting it simply: "We have one thing the Egyptians did not: We have hope."

Hope is a commodity more precious than crude. Programs initiated by King Abdullah over the last fifteen years, especially investments in health and science, have increased post-graduate education, created jobs, and expanded the roles available to women. These programs are founded on zakaat, one of the five pillars of Islam, the obligatory charity required of all Muslims of means. Abdullah’s programs are thus doubly invested — with cash and with spiritual capital.

Certainly, much remains distasteful about present-day life in Saudi Arabia: Women remain legal minors restricted in their independent movement, men and women lack the vote, and the ban on public expression is absolute. I experienced these restrictions personally while living and practicing medicine in the Kingdom. Less well-known is how some Saudis are successfully reforming their system while tackling these very challenges. In the tradition of early Islam, this reform is emerging from women.

My colleague, Dr. Maha Al Muneef, is a case in point. Muneef founded the National Family Safety Program, the first Saudi initiative to protect victims of domestic violence and child abuse, which received some funding from the king. Gathering her abayya around her diminutive figure, she entered police stations, emergency rooms and courthouses to teach Saudi men about the identification of battered women and broken children. In under a decade, she has founded 33 shelters where distressed Saudi nationals can seek safety, and she has launched two hotlines, one each for women and children in distress.

Soap Opera Features History's Bad-Boy Pope

As Eamon Duffy writes, "the subordination of religious zeal to political pragmatism could go no further."

VATICAN CITY (RNS) Modern popes have had their fans and detractors, but few would dispute their reputations for personal virtue. That's partly why the five most recent pontiffs -- including John Paul II, who will be beatified on May 1 -- are under formal consideration for sainthood.

But as the new television show The Borgias is about to remind us, it was not always thus. Billed as the "sordid saga" of the "original crime family," the eight-week drama series premieres Sunday (April 3) on the Showtime network with an episode about the 1492 election of Rodrigo Borgia as Pope Alexander VI.

Showtime's website calls Alexander (played by Jeremy Irons) a "wily, rapacious" patriarch who followed his "corrupt rise" to the papacy by committing "every sin in the book to amass and retain power, influence and enormous wealth." Alexander, who reigned until his death in 1503, has gotten bad press since the 15th century. A contemporary critic, the zealous church reformer Girolamo Savonarola, even claimed that the pope was doing the work of the Antichrist. Unsurprisingly, Alexander eventually had him executed.

In his recent history, Lives of the Popes, University of Notre Dame scholar Richard P. McBrien calls Alexander the "most notorious pope in all of history." Even William Donohue, the pugnacious head of the Catholic League who assailed Showtime for airing its "sensationalist" show during Lent, concedes that Alexander was an "extortionist who led a life of debauchery."

How bad was he? The Spaniard Borgia, the only non-Italian member of the conclave that elected him, made himself pope with the help of generous bribes, handing out offices and privileges accumulated since his uncle Pope Callixtus III had made him a cardinal at the age of 25.

During his 11-year papal reign, according to historian Eamon Duffy's Saints and Sinners, Alexander "was widely believed to have made a habit of poisoning his cardinals so as to get his hands on their property." When he assumed the throne at age 61, Alexander had eight illegitimate children "by at least three women," Duffy writes, and went on to father at least one more. While still a cardinal, Borgia was rebuked by Pope Pius II -- himself an author of erotic plays -- for holding an orgy where married women had been invited to attend without their husbands.

What's So Appealing about Orthodoxy?

I came to Orthodoxy in 2006, a broken man. I had been a devoutly observant and convinced Roman Catholic for years, but had my faith shattered in large part by what I had learned as a reporter covering the sex abuse scandal. It had been my assumption that my theological convictions would protect the core of my faith through any trial, but the knowledge I struggled with wore down my ability to believe in the ecclesial truth claims of the Roman church. For my wife and me, Protestantism was not an option, given what we knew about church history, and given our convictions about sacramental theology. That left Orthodoxy as the only safe harbor from the tempest that threatened to capsize our Christianity.

In truth, I had longed for Orthodoxy for some time, for the same reasons I, as a young man, found my way into the Catholic Church. It seemed to me a rock of stability in a turbulent sea of relativism and modernism overtaking Western Christianity. And while the Roman church threw out so much of its artistic and liturgical heritage in the violence of the Second Vatican Council, the Orthodox still held on to theirs. Several years before we entered Orthodoxy, my wife and I visited Orthodox friends at their Maryland parish. As morally and liturgically conservative Catholics, we were moved and even envious over what we saw there. We had to leave early to scoot up the road to the nearest Seventies moderne Catholic parish to meet our Sunday obligation. The contrast between the desultory liturgical proceedings at Our Lady of Pizza Hut and what we had walked out of in the Orthodox parish down the road literally reduced us to tears. But ugliness, even a sense of spiritual desolation, does not obviate truth, and we knew we had to stand with truth – and therefore with Rome – despite it all.

Renaissance Rendering of the Sacred and the Secular

ROME—Among High Renaissance Italian painters, Lorenzo Lotto (c. 1480-1556/7) stands out as both provincial and cosmopolitan. He spent much of his career in several small cities of the Marches region in central Italy, where he died a humble lay member of a religious order. Yet to a much further degree than more celebrated countrymen, including his collaborator Raphael and his fellow Venetian Titian, Lotto absorbed the influence of such great German contemporaries as Dürer and Grünewald.

In this show at the Scuderie del Quirinale, with over 50 works that span the length of Lotto's career and the range of his sacred and secular subject matter, reflections of the north are evident throughout; for instance, in the Gothic architecture of the Virgin's stiffly folded cloak as she appears to two saints in an altarpiece from the Asolo cathedral, and in the cold light that shines on the scene.

A relative unknown for centuries until American art historian Bernard Berenson championed him in 1895, Lotto was a fitting rediscovery for the age of Freud, since his work is marked by psychological tension of a piece with his anguished piety. The infant Jesus in his mother's arms reaches out with a baby's impulsiveness for his own pierced heart, proffered to him by a martyred saint; elsewhere he caresses a lamb with poignant innocence, suggesting the paradox of Christ's human nature, still unaware of the sacrificial symbolism in which his divine nature is engaged.

Among the 17 portraits in the show, a Dominican friar appears with his financial accounts, keys and coins, and no symbol of the divine in sight. The 1526 painting seems to modern eyes like a recruiting poster for the young Lutheran Reformation, a movement now believed to have held Lotto's guarded sympathy.

Connect the Quantum Dots for a Full-Colour Image

Nanocrystal display could be used in high-resolution, low-energy televisions.

Ink stamps have been used to print text and pictures for centuries. Now, engineers have adapted the technique to build pixels into the first full-colour 'quantum dot' display — a feat that could eventually lead to televisions that are more energy-efficient and have sharper screen images than anything available today.

Engineers have been hoping to make improved television displays with the help of quantum dots — semiconducting crystals billionths of a metre across — for more than a decade. The dots could produce much crisper images than those in liquid-crystal displays, because quantum dots emit light at an extremely narrow, and finely tunable, range of wavelengths.

The colour of the light generated depends only on the size of the nanocrystal, says Byoung Lyong Choi, an electronic engineer at the Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology in Yongin, South Korea. Quantum dots also convert electrical power to light efficiently, making them ideal for use in energy-saving lighting and display devices.

Easier said than done

Attempts to commercialize the technology have been hampered because it is difficult to make large quantum-dot displays without compromising the quality of the image. The dots are usually layered onto the material used to make the display by spraying them onto the surface — a technique similar to that of an ink-jet printer. But the dots must be prepared in an organic solvent, which "contaminates the display, reducing the brightness of the colours and the energy efficiency", says Choi.

Choi and his colleagues have now found a way to bypass this obstacle, by turning to a more old-fashioned printing technique — details of which appear today in Nature Photonics1. The team used a patterned silicon wafer as an 'ink stamp' to pick up strips of dots made from cadmium selenide, and press them down onto a glass substrate to create red, green and blue pixels without using a solvent.

How the End Begins

Ron Rosenbaum tells of how close—and how often—the world has come to nuclear annihilation, and why we are once again on the brink.

Build that Ramp to God

ORLANDO — In the Gospel of Luke, early Christians are urged to "invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind" (14:13) to their gatherings. But how far can — or should — modern religious congregations go to accommodate people with physical or intellectual disabilities?

With the Baby Boom generation about to age into infirmity, and wounded war veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan in growing numbers, the issue of worshippers with disabilities will very soon overwhelm ethical and theological abstraction.

But half the congregations in the USA have fewer than 100 members— many in small towns and rural areas — which means the financial cost of adjusting their structures, Sunday schools and weekly services for one or two hearing-impaired or autistic or wheelchair using members can be a challenge. Building a ramp out of plywood is one thing; installing an elevator is quite another.

St. Michael the Archangel Catholic Church in Levittown, Pa., a congregation with about 10,000 members, raised more than $100,000 in a campaign to install an elevator to the basement social hall to accommodate parishioners who use a wheelchair, as well as for a seniors' group.

Although the faith community was at the forefront of efforts to pass the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, religious institutions of all denominations with fewer than 15 full-time employees are essentially exempt from the legislation, making the decision to become accessible a voluntary matter. According to the Association of Religion Data Archives, in 2006, 98% of U.S. congregations had fewer than 15 full-time employees. For Catholics, who tend to have larger parishes, the figure is 87%.

Here, as elsewhere, the economies of scale apply. Megachurches are a lot like big box retailers and consolidated high schools in what services they can provide: Large congregations of all faiths are more likely to have resources and facilities to provide sophisticated programs for a spectrum of disabilities.

But even megachurches require motivation.

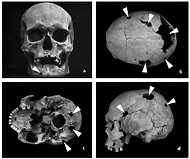

Unearthing Prehistoric Tumors, and Debate

When they excavated a Scythian burial mound in the Russian region of Tuva about 10 years ago, archaeologists literally struck gold. Crouched on the floor of a dark inner chamber were two skeletons, a man and a woman, surrounded by royal garb from 27 centuries ago: headdresses and capes adorned with gold horses, panthers and other sacred beasts.

But for paleopathologists — scholars of ancient disease — the richest treasure was the abundance of tumors that had riddled almost every bone of the man’s body. The diagnosis: the oldest known case of metastasizing prostate cancer.

The prostate itself had disintegrated long ago. But malignant cells from the gland had migrated according to a familiar pattern and left identifiable scars. Proteins extracted from the bone tested positive for PSA, prostate specific antigen.

Often thought of as a modern disease, cancer has always been with us. Where scientists disagree is on how much it has been amplified by the sweet and bitter fruits of civilization. Over the decades archaeologists have made about 200 possible cancer sightings dating to prehistoric times. But considering the difficulties of extracting statistics from old bones, is that a little or a lot?

A recent report by two Egyptologists in the journal Nature Reviews: Cancer reviewed the literature, concluding that there is "a striking rarity of malignancies" in ancient human remains.

"The rarity of cancer in antiquity suggests that such factors are limited to societies that are affected by modern lifestyle issues such as tobacco use and pollution resulting from industrialization," wrote the authors, A. Rosalie David of the University of Manchester in England and Michael R. Zimmerman of Villanova University in Pennsylvania. Also on the list would be obesity, dietary habits, sexual and reproductive practices, and other factors often altered by civilization.

Atheists Debate How Pushy to Be

LOS ANGELES — Energized by a recent Pew Research Center poll showing that atheists are more educated about religion than religious people, 370 atheists, humanists and other skeptics packed a ballroom at the Millennium Biltmore Hotel last weekend to debate the future of their movement.

They agreed on two things: People can be good without religion, and religion has too much influence. But they disagreed about how stridently to make those claims.

The conference, sponsored by the Council for Secular Humanism, drew members from all the major doubters’ organizations, including American Atheists and the American Humanist Association. The largely white and male crowd — imagine a Star Trek convention, but older — came to hear panels that included several best-selling atheist pamphleteers, like Richard Dawkins, author of "The God Delusion," and Sam Harris, who wrote "The End of Faith" and is a rock star in the atheist world (he traveled with bodyguards because he receives death threats from both Christians and Muslims).

The conference came on the heels of a change in leadership at the council and a rumored rift there, which some described as a standoff between atheists, who focus on God’s nonexistence, and humanists, who are also nonbelievers but seek an alternative ethical system, one that does not depend on any deity.

Some of the weekend’s speakers alluded to the turmoil at the council, where several longtime employees have resigned or been laid off. But in general they emphasized unity: They shared common enemies, like religious fundamentalism and "Intelligent Design." And they believed morality was possible without God.

The presenters did differ on where a secular morality might come from. In his new best seller, "The Moral Landscape," Mr. Harris argues that morality is a product of neuroscience. (The good, he argues, is that which promotes happiness and well-being, and those states are ultimately dependent on brain chemistry.) Others believe morality is bequeathed by evolution, while still others would argue for ethics grounded in secular philosophy, like Immanuel Kant’s or John Rawls’s. But all agreed that nonbelievers are at least as moral as believers, and for better reasons.

The disagreement was not, then, between atheism and humanism. It was about making the atheist/humanist case in America. A central question was, "How publicly scornful of religion should we be?"

Here even the humanists got less humane, as each side stereotyped the other. Those trying to find common ground with religious people were called "accommodationists," while the more outspoken atheists were called "confrontationalists" and accused of alienating potential allies, like moderate Christians.

At the liveliest panel, on Friday night, the science writer Chris Mooney pointed to research that shows that many Christians "are rejecting science because of a perceived conflict with moral values." Atheists should be mindful of this perception, Mr. Mooney argued. For example, an atheist fighting to keep the theory of evolution in schools should reassure Christians that their faith is compatible with modern science.

Benedict XVI to Visit Britain

Pope sees Europe's future within small Catholic flock.

Inside Westminster Cathedral, the mother church of Catholicism in England and Wales, bronze plaques commemorate the leaders of English Catholicism since the year 314.

The plaques are a pointed reminder that the Catholic Church is by far Britain's oldest existing institution, preceding even the monarchy by at least half a millennium.

The cathedral, however, didn't open until 1903, and is still very much a work in progress -- much like the small Catholic flock that Pope Benedict XVI will meet when he arrives Thursday (Sept. 16) for a four-day official state visit to the United Kingdom.

British Catholicism is, like the cathedral, a relatively youthful institution with an ancient heritage. While the bottom half of the cathedral is covered with multicolored marbles and glittering mosaics, its upper walls and vaults are bare brick, awaiting decoration as finances permit.

The Roman Catholic Church in Britain might seem to be of marginal interest to the pope; Britain's 5.3 million Catholics represent less than 10 percent of one of Europe's most secular countries, and a mere 0.5 percent of Benedict's worldwide flock.

Rummaging for a Final Theory

Unifying gravity and particle physics may come down to an old approach from the 1960s.

Turning the clock back by half a century could be the key to solving one of science’s biggest puzzles: how to bring together gravity and particle physics. At least that is the hope of researchers advocating a back-to-basics approach in the search for a unified theory of physics.

In July mathematicians and physicists met at the Banff International Research Station in Alberta, Canada, to discuss a return to the golden age of particle physics. They were harking back to the 1960s, when physicist Murray Gell-Mann realized that elementary particles could be grouped according to their masses, charges and other properties, falling into patterns that matched complex symmetrical mathematical structures known as Lie ("lee") groups. The power of this correspondence was cemented when Gell-Mann mapped known particles to the Lie group SU(3), exposing a vacant position indicating that a new particle, the soon to be discovered "Omega-minus," must exist.

During the next few decades, the strategy helped scientists to develop the Standard Model of particle physics, which uses a combination of three Lie groups to weave together all known elementary particles and three fundamental forces: electromagnetism; the strong force, which holds atomic nuclei together; and the weak force, which governs radioactivity. It seemed like it would only be a matter of time before physicists found an overarching Lie group that could house everything, including gravity. But such attempts came unstuck because they predicted phenomena not yet seen in nature, such as the decay of protons, says physicist Roberto Percacci of the International School for Advanced Studies in Trieste, Italy.

The approach fell out of favor in the 1980s, as other candidate unification ideas, such as string theory, became more popular. But inspired by history, Percacci developed a model with Fabrizio Nesti of the University of Ferrara in Italy and presented it at the meeting. In the model, gravity is contained within a large Lie group, called SO(11,3), alongside electrons, quarks, neutrinos and their cousins, collectively known as fermions. Although the model cannot yet explain the behavior of photons or other force-carrying particles, Percacci believes it is an important first step.

My Interview with Obama on His Christianity and the 'Muslim issue'

Long before last week's revelation that a large and growing chunk of Americans believe that the President is Muslim - and that only about one in three Americans correctly identify him as Christian - Barack Obama was battling misperceptions about his religion.

In early 2008, right as Obama was in desperate need of a win in the South Carolina primaries - he'd beaten Hillary Clinton in Iowa's first-in-the-nation caucuses but lost to her in subsequent contests in New Hampshire and Iowa - false rumors swirled that he was Muslim.

Obama's father was raised in a Muslim household, though the presidential candidate had repeatedly called him an agnostic, and Obama had spent time attending an Indonesian school where most students were Muslim. An e-mail smear campaign alleged that the White House hopeful was disguising his true faith.

In South Carolina, whose primaries were Obama's first electoral test in the Bible Belt, that was a big problem. Less than a week before South Carolina's primary, Obama began calling media outlets with large Christian audiences to set the record straight. His first such interview was with Beliefnet, where I was then political editor.

With Thursday's Pew poll showing that nearly one in five Americans think Obama is Muslim, our conversation from 2008 - conducted by phone while the future president sat aboard his grounded campaign plane - has become relevant again.

The Spark Rises in the East

China, driven by a desire for prestige and its own Nobel laureates, could soon lead the world in scientific research.

Science is rising in the east. China's strategies for economic development, which are centred on creating a world-beating science base, don't sound like much. They go by odd names: the 863 Programme and Project 211, for instance, and the Torch and Spark programmes. But they are proving to be more powerful than even the Chinese government could have hoped.

Last year, following a decade of phenomenal growth, China became the second-biggest producer of scientific knowledge in the world. In 1998, Chinese scientists published about 20,000 articles. In 2009, they produced more than 120,000. Only the US turns out more.

According to figures released this year by the US National Science Foundation, there are now as many researchers working in China as there are working in the US or the EU. The state is encouraging Chinese scientists trained in the west to return home, offering them enormous salaries and access to world-class laboratories. In 2008, for example, the molecular biologist Yigong Shi, one of Princeton University's rising stars, walked away from a $10m research grant to set up a lab at Tsinghua University in Beijing. In January, the Chinese equivalent of the US National Institutes of Health was unveiled with £150m in its pockets, which will be distributed to new medical research projects.

"China is focusing on developing an elite group of institutions and the performance of these is going to go on improving," says Jonathan Adams, director of research evaluation at Thomson Reuters in London and lead author of a 2009 report into China's scientific research strategies and achievements.

If present trends continue, China will be the world leader in science by the end of this decade. "There's going to be a new geography," Adams says. "The map that people have in their minds of where science is taking place will have to be adjusted." Scientists working in the west need to react, according to Xiaoqin Wang, director of a biomedical engineering centre that Johns Hopkins University runs jointly with Tsing hua University. "Collaboration will become more and more important," he says.

Canny European and North American scientists are already reaching out to China. The number of east-west collaborations has doubled in the past five years and organisations such as the UK Research Councils, the British Council and the US National Science Foundation have made brokering such partnerships a priority.

Physicists Get Political Over Higgs

A storm is brewing round the scientists in line to win the Nobel prize for predicting the elusive particle.

It hasn't even been found yet, but the elusive Higgs particle is already generating controversy. As feelings run high over a recent conference in France, the particle physics community are split over who should get credit out of the six theoretical physicists who developed the mechanism behind its existence.

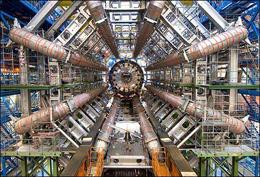

The Higgs particle is predicted to exist as part of the mechanism believed to give particles their mass, and is the only piece of the Standard Model of particle physics that remains to be discovered. Physicists at both the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, Europe's premier particle physics laboratory near Geneva in Switzerland, and the Tevatron accelerator in Batavia, Illinois, recently voiced their expectation that the particle could well be detected within the next few years.

This gave new urgency not only to the race to find the particle, but also to establishing authorship of the ideas behind it. As John Ellis, a particle physicist based at CERN, acknowledges: "Let's face it, a Nobel prize is at stake."

The authorship question is fraught because the mechanism was developed independently by three groups within a matter of weeks in 1964. First up were Robert Brout and François Englert in Belgium, followed by Peter Higgs in Scotland, and finally Tom Kibble in London, along with his colleagues in the United States, Gerald Guralnik (at the time in London) and Carl R. Hagen.

"There are six people who developed the mechanism in quick succession and who hold a legitimate claim to credit for it," says particle physicist Frank Close at the University of Oxford, UK.

Faith and Smart Phones Commune in Religion Apps

CEDARBURG, Wisconsin (Reuters) - Father Tom Eichenberger began a recent sermon by playing an iPhone ring tone of church bells into the microphone and talking about how praying is like using the popular mobile device.

"The same rules apply," he told the Sunday mass congregation at St. Francis Borgia Catholic Church in this small town north of Milwaukee.

"You don't just use your iPhone for phone calls, you have to use the apps," he said, referring to small programs that make the popular smart phones perform specific tasks.

"And you don't just use prayer to beg for things and treat God like Santa Claus," said Eichenberger, 60, reminding parishioners that prayers are also for giving praise or listening to the Spirit.

With smart phones boasting apps to do everything from finding convenient restaurants to identifying stars in the night sky, developers were bound to make programs that bring age-old religious practices into the digital world.

Many contain full texts of scriptures like the Bible or Torah. Muslims can calculate the times for their five daily prayers and Hindus can present virtual incense and coconut offerings to the elephant-headed god Ganesh.

Not all religious leaders are as enthusiastic as Eichenberger. But many recognize that youth often use new media like smart phones or Facebook to define themselves, interact socially and seek answers for their deepest questions.

"Technology is one way we project outward our sense of the self," said Rachel Wagner, assistant professor of religion at Ithaca College in New York. "Religion is an important part of the search for the self. Which apps people run says something about who they are."

Senegal Farmers Push Local Food Movement

Adherents of the local food movement argue: buying produce that’s grown nearby is good for the community, good for the planet and good for your health. Some farmers in the West African nation of Senegal are trying to make that case to their fellow countrymen, but it’s not so easy to get people to change their buying habits. The World’s Jori Lewis has the story.

********

MARCO WERMAN: Many environmentalists these days are proponents of the local food movement. They argue buying produce that’s grown nearby is good for the community, good for the planet, and good for your health. Some farmers in the West African nation of Senegal are trying to make that case, but they’ve found it’s not so easy to get people to change their buying habits. Jori Lewis has the story.

JORI LEWIS: In the north of Senegal as you near the border with Mauritania, the land becomes progressively more arid and brown, all sand dunes and scrubby brush, and you realize that you are close to the edge of the Sahara. But in the valley of the Senegal River they are growing what seems an unlikely crop: rice. Moustapha Fall comes from a family that’s been farming rice here for decades.

MOUSTAPHA FALL: It’s good quality rice that we can sell and that can feed the country.

LEWIS: Fall smokes non-stop while we drive to his fields in his pickup truck, past rows of green crops surrounded by water canals and dusty lanes. Farm workers take shelter under the shade of a spindly tree. Moustapha Fall says there are lots of challenges to farming here. There’s the price of fuel to run the irrigation pumps. There are the aggressive grain-eating birds. And there are periodic droughts. But he contends that the biggest threat to his livelihood as a rice farmer has nothing to do with the environment.

FALL: The biggest problem is actually selling the rice. Most of it just sits at the mill. You see over there, the mill? There’s a lot of rice stashed away there. It hasn’t been sold.

LEWIS: It’s not that people in Senegal dislike rice. On the contrary, most people here eat rice every day. The problem is that local rice farmers have to compete with imports. In Senegal’s capital, Dakar, I slide through a small doorway into the Tilene Market’s main food hall. Vendors man tables crowded with bags of rice from all over the world, places like Vietnam, the Philippines and India. There’s even rice from the US that comes packed in bags with the USAID logo. That rice is probably part of a US program that allows countries to sell food aid to raise money for development projects.

listen now or download mp3 audio, 4.5 minutes

How to Conquer the Invasive Lionfish?

Sauté it.

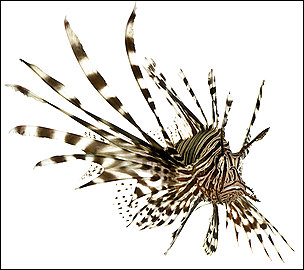

Lionfish makes for a stunning sight underwater, with its vibrant red hue and long, venomous spines. But it is also a relentless predator in U.S. and Caribbean waters, a trait that threatens coral reefs in the Southeast, Gulf of Mexico and beyond.

Sustainable-seafood advocates typically advise consumers to stay away from overfished, endangered species, but in this case they're taking the opposite tack. Federal officials have joined with chefs, spear fishermen and seafood distributors to launch a bold campaign: Eat lionfish until it no longer exists outside its native habitat.

Scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration theorize that the fish, a native of the western Pacific, was released from fish tanks in southern Florida sometime between the late 1980s and the early 1990s. By 2000 it had established itself off the North Carolina coast, and it has now expanded into the Caribbean and threatens to take over waters in South America and the Gulf of Mexico.

"There are some locations where lionfish have totally altered the biodiversity of a reef," said James Morris, a NOAA ecologist at the agency's Center for Coastal Fisheries and Habitat Research in Beaufort, N.C.

As a top predator, it consumes juvenile snapper and grouper along with algae-eating parrotfish, all of which help keep reefs healthy. Between 2004 and 2008, local densities of lionfish increased by roughly 700 percent in some areas; there are now 1,000 lionfish per acre on certain reefs.

In trying to create a consumer demand for lionfish, a handful of conservationists and restaurant industry experts are saying that humans are the only predator that can wipe it out. The Reef Environmental Education Foundation is preparing a cookbook to educate chefs on how to prepare the species, a delicate and sweet white fish that tastes like a cross between snapper and grouper.

"This fish is delicious," said seafood distributor Sean Dimin, co-owner of Sea to Table, who visited Beaufort last year and learned that divers were catching it in "lionfish rodeos" and cooking it on the beach.

Ignorance of Science

Who's to blame?

If the American public doesn’t "get" science issues, who is to blame — the many scientifically illiterate Americans or scientists themselves?

My Facebook friends were atwitter (no social media mixups intended here) with that question on Sunday in response to a Washington Post piece by science journalist Chris Mooney. He is the co-author, with Sheril Kirshenbaum, of "Unscientific America: How Scientific Illiteracy Threatens Our Future."

Ignorance of science is not the whole explanation for the mismatch between public opinion and scientific evidence on evolution, vaccinations, climate change and many other issues, Mooney asserts.

"As much as the public misunderstands science, scientists misunderstand the public," he says. "In particular, they often fail to realize that a more scientifically informed public is not necessarily a public that will more frequently side with scientists."

On climate change, for example, the gap between scientists and a good share of the public may not be due to a lack of information — but, instead, to deep-seated political loyalties, to the reality that politics trumps science on some issues.

"The battle over global warming has raged for more than a decade, with experts still stunned by the willingness of their political opponents to distort scientific conclusions," Mooney wrote. "They conclude, not illogically, that they're dealing with a problem of misinformation or downright ignorance — one that can be fixed only by setting the record straight."

Friends at the Top

Nick Clegg and David Cameron appear to get on well. But is friendship really a good basis for fair government?

Another day, another image of the nation's two new best friends: David Cameron and Nick Clegg. And doesn't it feel odd? It's not just about getting used to the "new politics", or the fact that during the election campaign they were at each other's throats. It's seeing a friendship at the helm that's disconcerting.

Of course, Gordon and Tony were friends too, sometimes. But they shared an ideology. Dave and Nick didn't and, it seems, could not have assembled a coalition without the personal chemistry. (Gordon couldn't do it because he didn't have enough warmth for Nick, as he implied in his farewell speech.) So should we be bothered, or should we welcome amity at the top, as part of our constitutional growing up?

Well, we might be bothered. The crux of the issue is that friendship embodies a very different set of values to democracy. Friendship is nothing if not particular and personal. Your friends are special individuals to you, and you treat them differently from others. To say one person is your friend is to imply others are not, and perhaps further that another again is your shared enemy. To be a friend is to be a favourite, and is to be treated favourably. It's why we get so nervous when friendship is visible in the workplace, deploying those ugly words "nepotism" and "cronyism" to describe it. A boss can be taken to court if they are seen to give friends preferential treatment. Friendship is profoundly unfair.

Immanuel Kant thought so. He believed that friendship was unethical. We don't act according to moral laws when we act with our friends. We go on how we feel, our whims, or a sense of loyalty. To put it philosophically, friendship is not amenable to universalisable imperatives, precisely because it is partial. If the golden rule is to do to all others as you would have them do to you, friendship contravenes it. Your friend will do far more for you than they'd do for others. Kant went so far as to say that there would be no friendship in heaven, it being a place of moral perfection.

The Menace of Denialism

Interview with Michael Specter

This week, we learned that J. Craig Venter has at long last created a synthetic organism—a simple life form constructed, for the first time, by man. Let the controversy begin—and if New Yorker staff writer Michael Specter is correct, the denial of science will be riding hard alongside it.

In his recent book Denialism: How Irrational Thinking Hinders Scientific Progress, Harms the Planet, and Threatens Our Lives, Specter charts how our resistance to vaccination and genetically modified foods, and our wild embrace of questionable health remedies, are the latest hallmarks of an all-too-trendy form of fuzzy thinking—one that exists just as much on the political left as on the right.