Reviews

How the Secular World Began

Lucretius' poem, recovered in 1417, described atomic theory, chance's role in nature and the gods' indifference.

We think of the Renaissance as a time of unsurpassed artistic accomplishment, but it was also a time of unrelenting strife. In the 14th century, the city-states of Italy were in constant turmoil; Milan warred against Venice, Florence against Rome. This was the period of the "Babylonian Captivity" of the church, when the papacy was established in Avignon, where it became a satellite of the French king. Central religious authority so disintegrated that eventually no fewer than three popes would simultaneously claim the chair of St. Peter. Reformers to the north began issuing denunciations of the church, denouncing a clergy and hierarchy that had grown ever more corrupt and licentious.

In this age of chaos and confusion, a small band of learned men, the Renaissance humanists, clung to a vision of the past that seemed to hold out some hope of tranquility. Antiquity offered models of noble conduct, but they survived only in broken statues or in the mildewed pages of manuscripts hidden for centuries in remote monasteries. To locate and copy manuscripts that contained the voices of the vanished past in all their unsurpassed eloquence became, for some scholars, an overmastering obsession.

The remarkable Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459) is hardly remembered today, even in his Tuscan hometown of Terranuova. Yet his discoveries led, by slow, almost imperceptible steps, to a revolution in Western thought. In "The Swerve," Shakespearean scholar Stephen Greenblatt traces Poggio's extraordinary career and legacy. He served as apostolic secretary to one of the three rival claimants to the papacy, John XXIII. He was a calligrapher of genius, creating elegant scripts (beautifully illustrated in one of Mr. Greenblatt's well-chosen plates). And he was a book-hunter of the most dogged sort.

Aided by his official position, Poggio used every skill at his command—diplomatic suavity, flattery, displays of erudition—to talk his way into otherwise inaccessible monastic libraries. Underlying his quest was a conviction that the good order of the world and of society depended upon a disciplined reverence for language, specifically the Latin language; true eloquence had a moral foundation. Though Poggio was responsible for many priceless finds—the works of Vitruvius and Quintilian, the letters of Cicero—it was thanks to his discovery in 1417 of the sole surviving manuscript of the Roman poet Lucretius' "On the Nature of Things" that, in Mr. Greenblatt's phrase, "the world swerved in a new direction."

Holy War: Why Vasco de Gama Went to India

The Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama set sail from Belém, a village at the mouth of the Tagus River now part of greater Lisbon, on July 8, 1497. An obscure but well- connected courtier, he had been chosen, much to everyone’s surprise, by King Manuel I to head the ambitious expedition to chart a new route to India. The king was not moved chiefly by a desire for plunder. He possessed a visionary cast of mind bordering on derangement; he saw himself spearheading a holy war to topple Islam, recover Jerusalem from "the infidels" and establish himself as the "King of Jerusalem."

Da Gama shared these dreams, but like his hard-bitten crew, rogues or criminals to a man, he coveted the fabled riches of the East — not only gold and gems but spices, then the most precious of commodities. On this voyage, as on his two later ones, he proved a brilliant navigator and commander. But where courage could not bring him through violent storms, contrary seas and the machinations of hostile rulers, luck came to his rescue. He sailed blindly, virtually by instinct, without maps, charts or reliable pilots, into unknown oceans.

As Nigel Cliff, a historian and journalist, demonstrates in his lively and ambitious "Holy War," da Gama was abetted as much by ignorance as by skill and daring. To discover the sea route to India, he deliberately set his course in a different direction from Columbus, his great seafaring rival. Instead of heading west, da Gama went south. His ships inched their way down the African coast, voyaging thousands of miles farther than any previous explorer. After months of sailing, he rounded the Cape of Good Hope, the first European to do so. From there, creeping up the east coast of Africa, he embarked on the uncharted vastness of the Indian Ocean. Uncharted, that is, by European navigators. For at the time, the Indian Ocean was crisscrossed by Muslim vessels, and it was Muslim merchants, backed up by powerful local rulers, who controlled the trade routes and had done so for centuries. Da Gama sought to break this maritime dominance; even stronger was his ambition to discover the Christians of India and their "long-lost Christian king," the legendary Prester John, and by forging an alliance with them, to unite Christianity and destroy Islam.

What Physics Owes the Counterculture

"What the Bleep Do We Know!?," a spaced-out concoction of quasi physics and neuroscience that appeared several years ago, promised moviegoers that they could hop between parallel universes and leap back and forth in time — if only they cast off their mental filters and experienced reality full blast. Interviews of scientists were crosscut with those of self-proclaimed mystics, and swooping in to explain the physics was Dr. Quantum, a cartoon superhero who joyfully demonstrated concepts like wave-particle duality, extra dimensions and quantum entanglement. Wiggling his eyebrows, the good doctor ominously asked, "Are we far enough down the rabbit hole yet?" All that was missing was Grace Slick wailing in the background with Jorma Kaukonen on guitar.

Dr. Quantum was a cartoon rendition of Fred Alan Wolf, who resigned from the physics faculty at San Diego State College in the mid-1970s to become a New Age vaudevillian, combining motivational speaking, quantum weirdness and magic tricks in an act that opened several times for Timothy Leary. By then Wolf was running with the Fundamental Fysiks Group, a Bay Area collective driven by the notion that quantum mechanics, maybe with the help of a little LSD, could be harnessed to convey psychic powers. Concentrate hard enough and perhaps you really could levitate the Pentagon.

In "How the Hippies Saved Physics: Science, Counterculture, and the Quantum Revival," David Kaiser, an associate professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, turns to those wild days in the waning years of the Vietnam War when anything seemed possible: communal marriage, living off the land, bringing down the military with flower power. Why not faster-than-light communication, in which a message arrives before it is sent, overthrowing the tyranny of that pig, Father Time?

That was the obsession of Jack Sarfatti, another member of the group. Sarfatti was Wolf’s colleague and roommate in San Diego, and in a pivotal moment in Kaiser’s tale they find themselves in the lobby of the Ritz Hotel in Paris talking to Werner Erhard, the creepy human potential movement guru, who decided to invest in their quantum ventures. Sarfatti was at least as good a salesman as he was a physicist, wooing wealthy eccentrics from his den at Caffe Trieste in the North Beach section of San Francisco.

Other, overlapping efforts like the Consciousness Theory Group and the Physics/Consciousness Research Group were part of the scene, and before long Sarfatti, Wolf and their cohort were conducting annual physics and consciousness workshops at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur.

The Final Testament of the Holy Bible is Shocking. Shockingly Bad, that is.

The problem with James Frey's book isn't blasphemy per se. Good blasphemy, unlike this adolescent theology, is valuable.

Blasphemy is in the news again, and this time it has nothing to do with the Qu'ran or the prophet Muhammad. The novelist James Frey has written a new life of Jesus, The Final Testament of the Holy Bible. It is set in contemporary New York in which a Jesus-figure, Ben, comes back among New York lowlife, as lowlife. His message is the old hippy one – love, love, love – which he pursues in very practical ways. He makes love to almost everyone he meets – women, men, drug addicts, priests. Hence the blasphemy.

Or at least, that is what the publishers are hoping. Written on the cover, in bold, we are told that this is Frey's most revolutionary and controversial work. "Be moved, be enraged, be enthralled by this extraordinary masterpiece," it screams in uppercase letters.

I hope people don't rise to the bait. The book is more ludicrous than scandalous. The rabbit-like lovemaking is accompanied by dialogue of the "we-screwed-until-dawn-and-it-was-like-being-joined-with-the-cosmos" type. And then there's the adolescent protest theology. Religion is responsible for all ills everywhere, Ben solemnly informs us. The Bible is a stone age sci-fi text. God is no more believable than fairies. Faith is just an excuse to oppress.

That said, the book did set me thinking about blasphemy. For it seems to me that there is good blasphemy and bad blasphemy. Good blasphemy is worth studying, whereas bad blasphemy is not. Good blasphemy conveys ethical and theological insights, whereas bad blasphemy is simply about complaint and shock. Both kinds of blasphemy might be published, but only the good type is worth spending time on. (It's a shame when bad blasphemy upsets believers and gains press coverage that encourages others to react to it.)

I was myself involved in a blasphemy case, one of the last to be investigated by the police before changes in British law. We'd published a banned poem, The Love that Dares to Speak its Name by James Kirkup. It strikes me now that while there were important principles of free speech to defend in the case, the poem itself is an example of bad blasphemy. It features a Roman centurion having sex with Jesus after his crucifixion, and is naive and clumsy, replete with ban puns about Jesus being "well hung". Aesthetically it's inept, ethically it's simplistic, theologically it's crass.

Hallelujah! At Age 400, King James Bible Still Reigns

This year, the most influential book you may never have read is celebrating a major birthday. The King James Version of the Bible was published 400 years ago. It's no longer the top-selling Bible, but in those four centuries, it has woven itself deeply into our speech and culture.

Let's travel back to 1603: King James I, who had ruled Scotland, ascended to the throne of England. What he found was a country suspicious of the new king.

"He was regarded as a foreigner," says Gordon Campbell, a historian at the University of Leicester in England. "He spoke with a heavy Scottish accent, and one of the things he needed to legitimize himself as head of the Church of England was a Bible dedicated to him."

At that time, England was in a Bible war between two English translations. The Bishops' Bible was read in churches: It was clunky, inelegant. The Geneva Bible was the choice of the Puritans and the people: It was bolder, more accessible.

"The problem with the Geneva Bible was it had marginal notes," says David Lyle Jeffrey, a historian of biblical interpretation at Baylor University. "And from the point of view of the royalists, and especially King James I, these marginal comments often did not pay sufficient respect to the idea of the divine right of kings."

Those notes referred to kings as tyrants, they challenged regal authority, and King James wanted them gone. So he hatched an idea: Bring the bishops and the Puritans together, ostensibly to work out their differences about church liturgy. His true goal was to maneuver them into proposing a new Bible. His plans fell into place after he refused every demand of the Puritans to simplify the liturgy, and they finally suggested a new translation. With that, James commissioned a new Bible without those seditious notes. Forty-seven scholars and theologians worked through the Bible line by line for seven years.

listen now or download Listen to the Story: All Things Considered

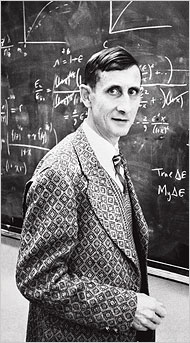

Richard Feynman, the Thinker

In the heyday of the physicist Richard P. Feynman, which ensued after his death in 1988, a publishing entrepreneur might have been tempted to start a book club of works by and about him. Offered as main selections would be Feynman’s autobiographical rambles (as told to Ralph Leighton), " ‘Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!’" and " ‘What Do You Care What Other People Think?’" For alternate selections, readers could choose from his more serious works, like "QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter" — a spirited account of the counterintuitive behavior of the quantum world — and the legendary "Feynman Lectures on Physics." Whatever the man said had swagger. For those who would rather listen, there are recordings of the lectures and of Feynman playing his bongos.

He was an irresistible subject for biographers and, as he called himself in two of his subtitles, a curious character indeed. The best biography, James Gleick’s "Genius," captured the ebullience — sometimes winning, sometimes exasperating — and gave lucid explanations of some hard physics. Those seeking a more mathematical treatment could turn to Jagdish Mehra’s thick book "The Beat of a Different Drum," while for a lighter touch there was Christopher Sykes’s "No Ordinary Gen ius: The Illustrated Richard Feynman."

It is hard to imagine that the world needs another Feynman biography, but here it is. In "Quantum Man: Richard Feynman’s Life in Science," Lawrence M. Krauss, director of the Origins Project at Arizona State University, makes his own way through the subject and emerges with an enlightening addition to the field. Krauss — like Feynman a physicist as well as an author — has written seven books, including "The Physics of Star Trek." Though he couldn’t resist recycling some well-worn Feynman anecdotes (and providing a couple of his own), he concentrates on Feynman the thinker, and on the contributions that merited his fame.

It is not something easily summarized. Einstein discovered relativity. Murray Gell-Mann discovered the quark. And Feynman? Well, there was that thing he did on TV with the O-ring and the ice water, showing why the Challenger had disintegrated. But to physicists he is famous for something more obscure: cleaning up the mathematical mess known as quantum electrodynamics — an ambitious attempt to explain light and matter using two great theories, quantum mechanics and special relativity.

Review: First Contact

Scientific Breakthroughs in the Hunt for Life Beyond Earth by Marc Kaufman

It wasn’t that long ago that the field of astrobiology—the search for life beyond Earth—operated towards the fringes of scientific endeavor, research many explicitly avoided being identified with, especially those seeking government grants or academic tenure. That’s changed, though, as scientists have both discovered life in increasingly extreme environments on the Earth as well as identifying locales beyond Earth, including beyond our solar system, which may be hospitable to life. There are now astrobiology conferences, astrobiology journals, and even a NASA Astrobiology Institute. It’s in that environment of increased acceptance that Marc Kaufman surveys the state of astrobiology’s quest to discover life elsewhere in the universe in First Contact: Scientific Breakthroughs in the Hunt for Life Beyond Earth.

Kaufman, a reporter for the Washington Post, covers a lot of ground in First Contact, both intellectually and geographically. For the book he traveled from mines in South Africa where scientists look for extremophiles living deep below the surface, to observatories in Chile and Australia where astronomers search for methane on Mars and planets around other stars, to conferences from San Diego to Rome where researchers discuss their studies. He uses this travel to provide a first-person account of the state of astrobiology today, neatly condensed into about 200 pages. It’s a good overview for those not familiar with astrobiology, although those who have been following the field, or at least some aspects of it, will likely desire more details than what’s included in this slender book.

One interesting portion of the book looks at those people who still work in—or have been exiled to—the fringes of astrobiology even as the field gains wider acceptance. "[P]erhaps because of its urge for legitimacy, or because the discipline itself so often enters terra incognita, astrobiology has shown a consistent need to enforce a consensus," casting aside those who differ, Kaufman writes. These people include Gil Levin, who argues the Labeled Release experiment on the Viking landers did, in fact, detect life on Mars; David McKay, who led the team that discovered what they still believe is evidence of life in Martian meteorite ALH 84001; and Richard Hoover, who claims to see similar evidence for life in other meteorites. All three get fair, if somewhat sympathetic, profiles in one chapter of the book; Kaufman goes so far to lament that the three, presenting in the same session of a conference, draw only a handful of people—nevermind that they’re speaking at a conference run by SPIE, an organization better known for optics and related technologies. (Since the book went to press, Hoover has gained notoriety for publishing a paper in the quixotic, controversial Journal of Cosmology about his asteroid life claims, an event that generated some media attention but was widely rebuffed as containing nothing new to support his claims.)

Rob Bell's Intervention in the Often Ugly World of American Evangelicalism

In its treatment of hell, the pastor's book holds two Christian truths in tension: human freedom and God's infinite love.

The question: Who is in hell?

I met Rob Bell at Greenbelt, a couple of years back, because we happened to be staying in the same hotel. Though at first, I didn't know who he was. Rather, I saw him coming. He was dressed head-to-foot in black and was accompanied by three other chaps, similarly clad, carrying those impressive silver cases that speak of expensive, hi-tech gear. Then, later, I saw the long queues for his event; they were heavily oversubscribed. I made the link with the inclusive megachurch American pastor who was topping the bill.

He draws congregations numbered in the tens of thousands. And now his new book, Love Wins, has achieved the ultimate accolade. A clever marketing campaign led to a top 10 Twitter trend at the end of February. Evangelicals, even liberal ones, believe the Word changes everything, and so they take words very seriously. They are entirely at home in the wordy, online age.

The row on Twitter is to do with the content of the book, or at least what a number of conservative megachurch detractors assumed to be the content. It's to do with universalism – the long debate in Christianity about whether everyone is eventually saved by Jesus, or whether only an elect make it through the pearly gates. Bell's opponents assume that he is peddling the message that when the great separation comes, between the sheep and the goats, there won't be any going into the pen marked "damnation".

From this side of the pond, it all feels very American, one of those things that makes you realise that the US is a foreign country after all. I'm sure that some British evangelicals debate the extent of the saviour's favour too, only they are also inheritors of the Elizabethan attitude about being wary of making windows into other people's souls. "Turn or burn!" works in South Carolina, not the home counties. (Then again, I was recently in a debate with someone who claimed to know Jesus better than his wife. I wondered whether his wife knew.)

Counting Down to Nuclear War

Every thousand years a doomsday threatens. Early Christians believed the day of judgment was nigh. Medieval millenarians expected the world to end in 1000 A.D. These fatal termini would have required supernatural intervention; in the old days humans lacked sufficient means to destroy themselves. The discovery, in 1938, of how to release nuclear energy changed all that. Humankind acquired the means of its own destruction. Even were we to succeed in eliminating our weapons of doomsday — one subject of "How the End Begins" — we would still know how to build them. From our contemporary double millennium forward, the essential challenge confronting our species will remain how to avoid destroying the human world.

Ron Rosenbaum is an author who likes to ask inconvenient questions. He has untombed the secrets of the Yale secret society Skull and Bones, tumbled among contending Shakespeare scholars and rappelled into the bottomless darkness of Adolph Hitler’s evil. But nothing has engaged his attention more fervently than doomsdays real or threatening, especially the Holocaust and nuclear war. Both catastrophes ominously interlink here.

The book wanders before it settles down. Rosenbaum speculates on the risk Israel took in 2007 when it bombed a secret Syrian nuclear reactor, a pre-emptive strategy Israel has followed since it destroyed an Iraqi reactor in 1981. He cites a quotation in The Spectator of London from a "very senior British ministerial source" who claimed that we came close to "World War III" the day of the attack on Syria. With no more information than the minister’s claim, the best Rosenbaum can say is that "it was not inconceivable."

He goes on to review the many close calls of the cold war, the continuing interception of Russian bombers by United States and NATO fighter aircraft, the negligent loading of six nuclear-armed cruise missiles onto a B-52 in August 2007 and their unrecognized transport across the United States. He works his way through these and similar incidents as if they prove much beyond the vulnerability of all man-made systems to accident, inadvertence and misuse.

Thinking the Unthinkable Again in a Nuclear Age

In his previous books the journalist Ron Rosenbaum has tackled big topics — Hitler’s evil, Shakespeare’s genius — with acuity and irreverence, believing, correctly, that some things are too important to leave to the experts. He’s proud of his gonzo amateur status, so much so that you half suspect he has a scarlet "A" tattooed across his chest, where Superman wore his "S."

Mr. Rosenbaum’s books are both profound and excitable. They resemble grad school seminars that have been hijacked by the sardonic kid in the back, the one with the black sweater and nicotine-stained fingers. Mr. Rosenbaum sometimes writes as if he were pacing the seminar room floor, scanning for sharp new ideas. At other times, it’s as if he were passing around red wine and a hookah, seeking to conjure deep, mellow, cosmic thoughts. He’s pretty good in both modes.

His new book, "How the End Begins: The Road to a Nuclear World War III," gives us both Mr. Rosenbaums, for better and occasionally for worse. This book is a wide-angle and quite dire meditation on our nuclear present; Mr. Rosenbaum is convincingly fearful about where humanity stands.

"I hate to be the bearer of bad news," he declares, "but we will all have to think about the unthinkable again." Our holiday from history is over.

Mr. Rosenbaum charts the likely origins of a nuclear war in the short term, probably in the Middle East (where Israelis fear a second Holocaust, this time a nuclear one) or Pakistan (where stray nukes may yet land in the hands of Islamists) or in the almost marital tensions and miscommunications between the United States and Russia. He pursues thorny moral questions, including this one about nuclear retaliation: "Would it be justice, vengeance or pure genocide to strike back" once our country had been comprehensively bombed?

"How the End Begins" is grim enough that, by its conclusion, you may feel like shopping for — depending on your temperament — either shotgun shells or the kind of suicide pills that spies were said to have sewn into their clothes when dropped behind enemy lines.

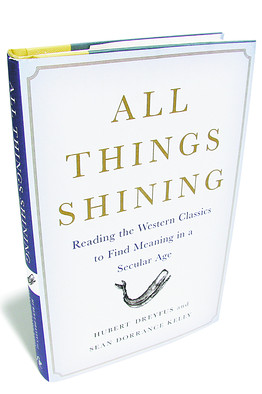

The Gods Return

A solution to the 'lostness' of the modern world

For the ancient Greeks, the universe was filled with shining presences that reflected the passing moods of the gods. Each god had a privileged sphere: Mars presided over war, Aphrodite over sexual love, Hera over the hearth; Zeus was the lord of all the gods, the hurler of thunderbolts from on high; and so on for the entire rowdy pantheon. It has long been customary to dismiss these gods as mere stage presences, as convenient explanations for random catastrophes or as fall guys for human motives. Helen caused the Trojan War but, hey, "golden Aphrodite" made her do it.

The authors of "All Things Shining" will have none of this. Though both are professional philosophers—Hubert Dreyfus at Berkeley and Sean Dorrance Kelly at Harvard—they view the ancient Homeric gods as hidden presences still susceptible of invocation. Indeed, they hold out "Homeric polytheism" as a solution to the "lostness" of the contemporary world. They begin by stating that "the world doesn't matter to us the way it used to." They are concerned to elucidate why this may be so. But this is no bland academic exercise. "All Things Shining" is an inspirational book but a highly intelligent and impassioned one. The authors set out to analyze our contemporary nihilism the better to remedy it.

And they provide, really, several books in one. "All Things Shining" provides a concise history of Western thought, beginning with Homer and concluding with Descartes and Kant. But there are extended discussions as well of such contemporary authors as the late David Foster Wallace and, even more startling, of "chick lit" novelist Elizabeth Gilbert. Among much else, the authors contrast Wallace's fraught, "radical" idea of individual freedom and autonomy to Ms. Gilbert's pre-Renaissance view of creativity, according to which "writing well" happens, as the authors put it, "when the gods of writing shine upon her."

A discussion of Odysseus's encounter with his wife Penelope's suitors—who try to kill him at the end of "The Odyssey"—is illumined by a comparison with the scene in the movie "Pulp Fiction" in which Jules and Vincent argue over whether their close call with a gunman was a miracle or merely a statistical probability. In the book's impressive chapter on Melville and "Moby Dick," the authors argue that the wildly changeable tones and shifts of subject matter in the novel are a key to its meaning. To take our moods seriously—"both our highest, soaring joys and our deepest, darkest descents"—is, for Melville, "to be open to the manifold truths our moods reveal."

The authors' general theme, and lament, is that we are no longer "open to the world." We fall prey either to "manufactured confidence" that sweeps aside all obstacles or to a kind of addictive passivity, typified by "blogs and social networking sites." Both are equally unperceptive. By contrast, the Homeric hero is keenly aware of the outside world; indeed, he has no interior life at all. His emotions are public, and they are shared; he lives in a community of attentiveness. He aspires to what in Greek is termed "areté," not "virtue," as it is usually translated, but that peculiar "excellence" that comes from acting in accord with the divine presence, however it may manifest itself.

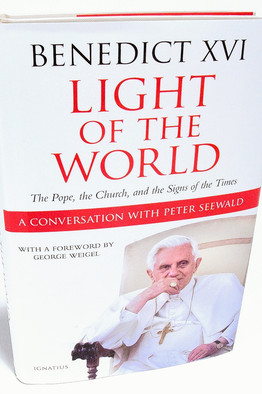

The Pontiff Speaks

Benedict sits down for several hours of conversation with a journalist.

'The monarchy's mystery is its life," the English writer Walter Bagehot wrote in 1867. "We must not let in daylight upon the magic." A turning point in the history of the British crown, according to some observers, was the 1969 BBC documentary "Royal Family," which showed Queen Elizabeth and her relations engaged in TV-watching and other activities of ordinary folk. The broadcast endeared the royals to millions but may have helped to dispel the larger-than-life aura on which their prestige depended.

Will future historians of the papacy say the same about "Light of the World"? Based on six hours of interviews with Pope Benedict XVI conducted in July of this year by the German journalist Peter Seewald, the book offers a rare portrait of a reigning pontiff, presenting him as insightful and eloquent—and pious of course—but also all too human.

Benedict confesses to TV-watching of his own: the evening news and the occasional DVD, especially a series of movie comedies from the 1950s and 1960s about a parish priest sparring with the Communist mayor of his Italian town. Despite such pleasures, the pope finds that his schedule "overtaxes an 83-year-old man" and reports that his "forces are diminishing," though he makes it clear that he still feels up to the demands of his office.

When it comes to recent controversies, Benedict voices gratitude to journalists for recently exposing the clerical sex abuse in several European and Latin American countries. He goes on to claim that "what guided this press campaign was not only a sincere desire for truth, but . . . also pleasure in exposing the Church and if possible discrediting her." While there is doubtless much truth to such a statement, blaming the messenger is the last thing an image consultant would advise a leader to say in a crisis—which suggests that the image of Benedict that appears here is as uncensored as Mr. Seewald claims.

Likewise, concerning the uproar that greeted Benedict's 2009 decision to lift the excommunication of Richard Williamson—the ultra-traditionalist bishop who turned out to be a Holocaust denier—the pope sees evidence, in the press, of "a hostility, a readiness to pounce . . . in order to strike a well-aimed blow." In this case, Benedict concedes that he made a mistake—that he would not have readmitted Bishop Williamson to the Catholic Church had he known about his statements on the Nazi genocide. "Unfortunately," he tells Mr. Seewald, "none of us went on the Internet to find out what sort of person we were dealing with."

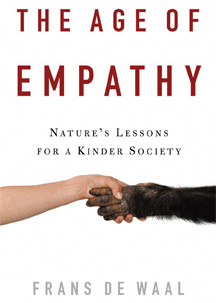

The Age of Empathy

Nature's Lessons for a Kinder Society

This is a confused book because it is trying to do several things at once. It is partly a study of animal empathy, the area of work for which Frans de Waal is well known. But de Waal is also fighting other battles, notably over whether there are sharp dividing lines between humans and other animals. And here he is much less sure of his ground.

The difficulty is that, in stressing the co-operative side of animal behaviour, de Waal sidelines an important trait on which human difference turns: cognition. It was not a mistake Charles Darwin made when, in The Descent of Man (1871), he noted that although animals have "well-marked social instincts", it is "intellectual powers", such as humans have, that lead to the acquisition of the moral sense of right and wrong.

The book fails when it comes to the third goal de Waal sets himself: to champion empathy as a solution to social, even political, problems. He resists the notion that empathy is innately morally ambivalent, overlooking how sadistic behaviour, for example, arises from empathising with a victim, too. Occasionally he admits that empathy is psychologically complex, but rather than exploring this complexity, he quickly returns to reciting evidence more congenial to his thesis.

He briefly offers a more sophisticated account of emotional connectivity, but again ignores its ramifications. This is a hierarchical model, and begins with the inchoate feelings that arise from witnessing another's exhilaration or distress. Next, there is "self-protective altruism" - doing something that benefits another person, though only in order to protect yourself from unpleasant emotional contagion. Then there is "perspective-taking", which is stepping into the shoes of another. But it is not unless the individual has a further capacity, sympathy, that he or she knows how to improve the lot of others. What distinguishes sympathy is that it allows both emotion and understanding (Darwin's "intellectual powers") to be brought to bear on the situation at hand.

Such faculties, however, are not the basis for moral behaviour that de Waal seeks. Indeed, he "shudder[s] at the thought that the humaneness of our societies would depend on the whims of politics, culture, or religion". One may shudder with him, but one might shudder more if our ability to act humanely rested solely on the morally flawed capacity of empathy.

Morality Without Transcendence

Can science determine human values?

When anthropologists visited the island of Dobu in Papua New Guinea in the 1930s they found a society radically different from those in the West. The Dobu appeared to center their lives around black magic, casting spells on their neighbors in order to weaken and possibly kill them, and then steal their crops. This fixation with magic bred extreme poverty, cruelty and suspicion, with mistrust exacerbated by the belief that spells were most effective when used against the people known most intimately.

For Sam Harris, philosopher, neuroscientist and author of the best-selling The End of Faith and Letter to a Christian Nation, the Dobu tribe is an extreme example of a society whose moral values are wrong. In his new book, The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values, Harris sets out why he believes values are not, as is widely held, subjective and culture-dependent. Instead, he says, values are a certain kind of fact — facts about the well-being of conscious creatures — and that they can therefore, at least in principle, be objectively evaluated. The "moral landscape" of the title is the concept that certain moral systems will produce "peaks" of human well-being while others, such as that of the Dobu, will lead to societies characterized by a slough of suffering. Harris maintains that it is possible to determine objectively that the former are better than the latter.

Harris is not the first person to advocate an objective basis for morality. The biologist E. O. Wilson, for example, has previously explained how he believes moral principles can be demonstrated as arising objectively from human biological and cultural evolution. But in arguing that there is an objective basis to morality, Harris puts himself at odds with a principle put forward by the 18th century philosopher David Hume and regarded as inviolable by many philosophers and scientists today: the idea that statements about how things ought to be cannot be derived from statements about what is true. In other words, it is impossible to derive values from facts.

Harris dismisses both this reasoning and the objection that there are no grounds for favoring his moral framework over any other. He takes it to be essentially self-evident that morality is about well-being, arguing that some practices, such as forcing women to dress head to toe in a burqa, are bound to reduce well-being. In Harris’s view, it is not right to treat all cultural practices as being equally valid and maintains that multiculturalism and moral relativism are wrong.

God and Philosophy in Hawking's Universe

Given that the celebrated physicist's thought is bathed in philosophical theories, it's folly to assert that science has dispatched metaphysics.

"Philosophy is dead." Stephen Hawking (2010)

"Philosophy always buries its undertakers." Etienne Gilson (1949)

Upon reading "The Grand Design," one gets the impression that Stephen Hawking has come a little late to the party. Sure, he manages to pronounce philosophy dead on page one of his new book, but philosophers have been heralding the death of philosophy for centuries.

Indeed, virtually every generation has produced at least a few philosophers who describe their subject as either finished or futile. It's doubtful Hawking is aware of this, though, since "The Grand Design" provides abundant evidence that the celebrated physicist's philosophical education has been sorely neglected.

Most people won't be particularly troubled by that, of course. What has troubled people--and consequently rocketed "The Grand Design" up the bestseller lists--is Hawking's claim that, "It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going."

Yet God and philosophy are intimately related in Hawking's universe, for it is the same philosophy--yes, philosophy -- that tried to kill them both. In "The Universe in a Nutshell," published in 2001, Hawking called this philosophy "positivist," and described positivism as an "approach put forward by Karl Popper and others." Now let's stop right there, since this is example No. 1 of Hawking's philosophical ignorance. For Popper did not "put forward" positivism; on the contrary, he argued vehemently against it. In fact, he devoted an entire section of his autobiography to explaining how he was responsible for destroying positivism.

Self-Made Golem

Simon Wiesenthal, painted in a new biography as a fame-seeking myth-maker, is also the man who insisted that the world face up to the Holocaust.

Stop the presses! Are you sitting down? Can you handle the truth? According to Tom Segev’s new biography of Simon Wiesenthal—and I’m not making this up—the famed Nazi hunter was not a perfect human being! He was a media manipulator, a myth-maker, a publicity seeker. He could be a self-aggrandizing credit grabber, a teller of tall tales and much-varied narratives, and sometimes weaver of outright fabrications. He was quarrelsome, vain, egotistical, didn’t play well with others.

But what would we have done without him? To many Jews, especially in the Diaspora, he gave at least the illusion that some of the perpetrators would be brought to justice. "Justice not vengeance," as Wiesenthal liked to say.

Segev, an indefatigable historian and highly respected reporter for the leftist Israeli daily Haaretz, tells us he had access to 300,000 Wiesenthal-related documents, although he doesn’t say how many he read. (Among his many human sources are agents of the Mossad who believe they deserve credit for some of his successes.) But his attempt at de-mythologizing Wiesenthal can sometimes make one feel he misses the forest for the trees. Yes, the Wiesenthal behind the legend may have been all too human, and it’s always valuable to set the record straight for history, but could this be a case where the legend is more important to the course of history than the life? Is publicity-seeking intrinsically bad if one is seeking to publicize the untroubled afterlives of mass murderers in order to shame the world into action?

The fact that this question has to be asked is due to something we have chosen to forget: the world community’s stunning failure after World War II to treat the Final Solution as a crime unto itself. The 19 Nazis convicted at Nuremberg were found guilty of "crimes against humanity" mainly for planning and starting a devastating war of aggression. Wiesenthal, Segev reminds us, was always adamant that the Final Solution was a crime against humanity as well as against Jews. But it was a different crime from that for which the Nazi leaders were tried at Nuremberg.

There was a lamentable loss of distinction between the two crimes, or rather a shameful failure to prosecute the second crime, for some 15 years after the war. Hitler lost the war against the Allies, yes. But in effect he won his personal "war against the Jews" (as Lucy Dawidowicz described his greatest priority) by a factor of some 6 million to one.

Den of Antiquities

In a remarkable interlude in Willa Cather’s novel "The Professor’s House," a New Mexico cowboy named Tom Outland describes climbing a landmark he calls Blue Mesa: "Far up above me, a thousand feet or so, set in a great cavern in the face of the cliff, I saw a little city of stone, asleep. It was as still as sculpture, . . . pale little houses of stone nestling close to one another, perched on top of each other, with flat roofs, narrow windows, straight walls, and in the middle of the group, a round tower. . . . I knew at once that I had come upon the city of some extinct civilization, hidden away in this inaccessible mesa for centuries."

Blue Mesa was Cather’s stand-in for Green Mesa — Mesa Verde in southern Colorado — and she was evoking what a real cowboy, Richard Wetherill, might have felt when, a week before Christmas 1888, he found Cliff Palace, the centerpiece of what is now Mesa Verde National Park. Craig Childs understands these kinds of epiphanies, and he beautifully captures them in "Finders Keepers: A Tale of Archaeological Plunder and Obsession" — along with the moral ambiguities that come from exposing a long-hidden world.

Wetherill’s city of stone, Childs reminds us, was quickly commandeered by a Swedish archaeologist who, over the objections of outraged locals, shipped crates of Anasazi artifacts to Europe. Worse things could have happened. Childs tells of a self-proclaimed amateur archaeologist who in the 1980s removed hundreds of artifacts from a cave in Nevada, including a basket with the mummified remains of two children. He kept the heads and buried the bodies in his backyard.

William Blake's Picture of God

The muscular old man with compasses often taken to be Blake's God is actually meant to be everything God is not.

Go to see the newly acquired etchings by William Blake at Tate Britain, or take a look online. They display all the unsettling power and apocalypticism we expect from this exceptional, romantic artist. One shows a young man tethered to a globe of blood by his hair. In another, someone burns in a furnace. Underneath, Blake has written lines such as, "I sought pleasure and found pain unutterable," or, "The floods overwhelmed me."

What you won't find in the gallery, though, is any explanation of these visions. Instead, Blake is treated as impenetrable, his imagery obscure, his calling idiosyncratic. He's rendered slightly mad, and so safe. We can look and admire, but like a modern gothic cartoon strip – that his art no doubt influences – he can be enjoyed, but not taken too seriously.

That's a shame. For not only can Blake be read. What he says carries at least as much force today as it did two hundred years ago.

Consider one of the figures who's in the new works: Urizen. He's well known as he's the same figure who appears as Blake's famous "Ancient of Days" – an old man, with Michelangelo muscles, a full head of long white hair, and a wizard-like beard. Urizen is a key figure in Blake's mythology.

He is not God. (Blake thought it laughable to imagine the divine as a father-figure, as God is found within and throughout life, he believed, hence referring to Jesus as "the Imagination.") Instead, Urizen is the demiurge, a "self-deluded and anxious" forger of pre-existent matter, as Kathleen Raine explains. His predominant concern with material things is signified by his heavy musculature. He is variously depicted as wielding great compasses, absorbed by diagrams, lurking in caves, and drowning in water – as in the new Tate image. It shows that his materialism has trapped him.

Blake loathed the deistic, natural religion associated with Newton and Bacon. He called it "soul-shuddering." Materialism he dismissed as "the philosophy in vogue." He thought the Enlightenment had created a false deity for itself, one imagined by Rousseau and Voltaire as projected human reason. The "dark Satanic mills" of Jerusalem are the mills that "grind out material reality", as Peter Ackroyd writes in his biography of Blake, continuing: "These are the mills that entrance the scientist and the empirical philosopher who, on looking through the microscope or telescope, see fixed mechanism everywhere."

Islam's Problem

In the annals of well-meaning ineptitude, Western efforts to locate and support moderate Muslim voices deserve a place of distinction. The story begins in the smoky rubble of Manhattan’s Twin Towers and the dawning awareness that Islamist zealots who styled themselves holy warriors were the masterminds of this startling act of mass murder. Such acts had to be understood either as something frightfully sick about Islam or as a radical distortion of Islam. Most reasonable people chose to see them as the latter. But if Islam was being hijacked, who within the Islamic world would resist?

Voices of moderation were hastily sought. Understandably, mistakes were made. Even among the Muslims mustered to stand in solidarity with President George W. Bush at the 9/11 memorial service in Washington National Cathedral were a couple whose credentials as champions of moderate, mainstream Islam were questionable. But if that was forgivable because of haste, later missteps were less so.

Wall Street Journal reporter Ian Johnson deftly recounts one such fiasco in a recent issue of Foreign Policy. In 2005, the U.S. State Department cosponsored a conference with the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) that brought American Muslims to Brussels to meet with 65 European Muslims. The State Department followed up by bringing European Muslims, many of whom had connections to the Muslim Brotherhood—the world’s oldest and arguably most influential Islamist organization, dedicated to making Islam a political program—to the United States for an ISNA-led summer program and imam training. The rationale was that European Muslims, thought to be less integrated into their adopted countries than American Muslims, would learn something valuable about assimilation. All well meaning, of course, but comically misguided. As Johnson notes, "ISNA was founded by people with extremely close ties to the European leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood."

This initiative was only the beginning of protracted efforts by U.S. officialdom to court a number of Brotherhood or Brotherhood-related Islamist organizations and leaders. Instant experts on political Islam from both liberal and conservative Washington think tanks advocated the idea of engaging Islamists who eschewed violence (except, in some cases, violence against Israelis) and endorsed the democratic process, if not liberal values. European officials were wary of this approach, but even the CIA gave a go-ahead.

The folly of this kind of thinking is a major concern of the books under review. In an essay in The Other Muslims, Yunis Qandil, a Jordan-born Palestinian and a lecturer at the Institute of Contemporary Intellectual Studies in Beirut, goes to the heart of the problem: "In the long term, the strengthening of ideological Islam and the granting of official recognition to its ‘moderate’ organizations against jihadism create more problems for us than solutions." Moderate as these Muslim groups in Europe and America may seem, Qandil explains, they represent what moderate, traditional Muslims fight against in their countries of origin: "the instrumentalization of our religion through a totalitarian ideology." While paying lip service to the values of Western societies—notably, the tolerance that allows them to operate—these Islamists fundamentally view such societies as the "archenemy of Islam." So why, Qandil reasonably asks, are European governments "still selecting the adherents of this particular type of Islam as their privileged partners and the recognized representatives of all Muslims"? The same question applies in the case of America.

The Language God Talks

A search for the secrets of eternity

This hodge-podgey little book has at least two very moving high points.

The second is a closing coda: the fictional Aaron Jastrow's sermon, "Heroes of the Iliad," delivered at the Theresienstadt concentration camp. It appears in Wouk's massive World War II novels Winds of War and War and Remembrance.

Jastrow invokes the book of Job. He ponders cruelty, suffering, injustice in creation. He concludes that Job, "the stinking Jew" who upholds Almighty God in the face of an unavailing universe, who calls God to acknowledge that "injustice is on his side," performs an essential service, for he, in upholding God, upholds humanity.

But the first high point is just as gripping. It's an imagined walk-and-talk between Wouk and physicist/Nobelist Richard Feynman. An aggressive, jokey unbeliever, Feynman questions Wouk about Talmud. He's curious why Wouk is Orthodox. Wouk tries to explain, "Not to convince you of my view, but because you asked me."

Throughout his long writerly career, Wouk, who turned 95 on May 15, has often pondered belief. In The Language God Talks (a title derived from Feynman's nickname for calculus), Wouk embraces science, assents to the connection between the human mind and the big bang. In the laws science has discovered, he hears a language God talks, and he feels we should listen.

This modest and not terribly well-focused book has inherent drama, for it faces nothing less than a huge shift, among some Jews, away from God. The break was the Holocaust. The argument goes: In light of such unanswered injustice, six million unanswered injustices, to cling to the notion of a just God is an obscenity, a way to smooth over, to seek comfort when comfort is unjust. To forget. For some, it is wrong even to question this break.

The 20th century saw an exhaustive effort to backfill the tradition, an effort that remains the subject of vigorous disagreement throughout all branches of Judaism. The brilliant, indispensable Jewish insistence on questioning, on debate, on weighing and sifting all sides, was mined for an unbroken skeptical tradition without the God of the Psalms. Atheist Jews could now claim that atheism was always Jewish.

The Shock Philosopher

On the provocative thinking of Simone Weil

Simone Weil was born in Paris just over a century ago, on February 3, 1909, and though she always remained fiercely loyal to France—and was French to her fingertips—the case could be made that her true homeland lay elsewhere, deep in the hazier and far more fractious republic of Contradiction. There she was, however perilously, chez elle. Weil displayed alarming aplomb on the horns of dilemmas; often she teetered on several simultaneously. She went after the paradoxical, the contradictory, the oppositional, with the rapt single-mindedness of a collector and the grim fervor of a truffle-hound. She exulted in polarities. Though many of Weil’s statements have an aphoristic cast or masquerade as bons mots, they are anything but witty in the usual bantering sense. Weil is an irritating thinker; her words impart an acrid aftertaste; they leave scratchy nettles behind. She meant to provoke, to jostle, to unsettle—she was an activist as well as a contemplative—and the play of opposition served this purpose.

But Weil also saw the summoning of opposites as a way of knowing. It was an ancient way, much favored by her beloved Greeks: the Stoic Chrysippus taught that we discern good and evil only by their opposition; in one of Heraclitus’s fragments, he is reported as saying, "God: day, night; winter, summer; war, peace; satiety, hunger." The dark saying could have been Weil’s own. For her, truth was to be found, if at all, in the tension of antinomies. Her thought, at its most perceptive as at its most repellent, draws its remarkable energy from that tension.

Weil’s life, too, was rife with contradiction, much of it in keeping with a familiar modern pattern. Born into a well-off, middle-class Jewish family, she was, over the course of her short life, now a Bolshevik, now an anarchist, now a labor union activist, now a (reluctant) combatant on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War and, after 1937, as a result of some sort of mystical experience in Assisi, a fervent Roman Catholic believer (though she refused to be baptized). In each of these metamorphoses, she found herself embroiled in opposition; she could not join a group or a movement or an institution without almost immediately dissociating herself from it.

Reasons to Think

At the Guardian Hay debate on reason, atheists and believers found more common ground than might be expected.

People are worried about reason, if the large numbers who attended the Guardian's debate at Hay is anything to go by. It proposed the motion "Reason is always right".

But what do we mean by reason? Why the worry? The philosopher, AC Grayling, kicked off the discussion in favour of the motion with a definition. Reason is the quality we want our doctors to practice when diagnosing our complaint. It's the discipline we want engineers to have when designing a passenger plane. It's that approach to life which we call enlightened, scientific. It gathers information, tests evidence, asks questions.

The word "rational" is close to the word ratio, or being proportionate. So, the good life is one in which passions and emotions don't run riot too. They are kept within reasonable limits. Thinking is what makes us human, Grayling averred. When our appetites take over, we come to harm. Hence, at the end of the day, reason is indeed always right.

Not so!, interjected the second speaker, Richard Harries, the former bishop of Oxford. He told of two women arguing, as they stood on the doorsteps of their respective houses. The couldn't agree because they were arguing from different premises. Ho-ho. But behind the joke lies a serious human issue. Rational discussions are very hard to have because we come to any encounter with jealousies, rivalries, prejudices and assumptions. "In my experience, very few people are capable of arguing objectively," said Harries, who is also a member of the House of Lords.

In other words, reason itself is not enough. We need judgment and wisdom, and that requires the moral and spiritual disciplines of conscience and intuition too. The truly wise individual, who can engage in debate well, is the person who can draw on these other capacities. Reason is not always right because reason alone is not enough.

Martin Rees, the distinguished scientist whose Reith lectures start this week, spoke next, in favour of the motion – but only just. He confessed to being a "cross-bencher" when it came to reason. It's vital, of course. It should hone arguments and test consistency. And scientific knowledge must be backed by reason. But for human beings, there always comes a point when we hit something that is unconditional for us. Respect for life would be one example. Reason helps to clarify why that's the case, but the principle itself is somehow prior to reason. Reason should take us as far as it can, Rees pressed, but it won't take us all the way.

Religion Confuses Even the Best Minds

Religion confuses even the best minds -- and maybe the best minds most of all. Chalk that up partly to the contempt most modern intellectuals have felt for the "opiate of the people." That attitude is hardly conducive to deep understanding, and in fact has given rise to a number of popular misconceptions. One is that modernization -- and its handmaidens, mass education and science -- would lead inevitably to the long-heralded twilight of the gods. We would all be good secular humanists one day soon.

Confidence in that particular shibboleth took a bad hit in the last decade or so. In addition to 9/11 and other acts of faith-based zealotry, Americans witnessed the boisterous return of religion to their public square. Other evidence from around the world -- whether it's the assertive role of Hinduism in contemporary Indian politics or the renewed interest in Confucian principles in still nominally communist China -- has made it much harder to think that religion is a spent force.

Intellectuals friendly to religion have fostered an equally misleading notion, one that is thoughtfully dispelled in Stephen Prothero's book, "God is Not One." Seeing the world's major belief systems through Enlightenment-tinted glasses, a succession of influential philosophers, artists, scholars and even many religious leaders have tended to minimize the differences of ritual and dogma among the various religions to emphasize a supposedly universal and benign truth shared by them all. Such well-meaning believers (and they do constitute a kind of religion of their own) have subscribed to variations of the Dalai Lama's affirmation that "the essential message of all religions is very much the same."

It's an uplifting bromide, to be sure, and Prothero, a professor of religion at Boston University, gives its supporters their due. The Golden Rule and other ethical principles are indeed shared by a majority of the world's religions. The mystical traditions of many religions employ similar disciplines and aspire to similar ends, whether transcendence of baser desires or a sense of unity with a supreme being.

But if the devil is in the details, the point of Prothero's useful book is that God is, too. Which is to say that the particular and often problematic features of a religion -- from its core narratives and rituals to its arcane points of theology -- are at least as important to its followers as those qualities that it may share with other religions. The universalist impulse may be a "lovely sentiment," Prothero writes, "but it is dangerous, disrespectful, and untrue."

Bad Science, Bad Theology, and Blasphemy

ID is indeed bad theology. It implies that God is one more thing along with all the other things in the universe.

The question: Is intelligent design bad theology?

You may have caught some of the row that followed Thomas Nagel's recommendation, in the literary pages of the TLS, for 2009 books of the year. He ventured Stephen Meyer's Signature In The Cell: DNA And The Evidence for Intelligent Design. Nagel is one of the most distinguished philosophers living today. And yet, that apparently now stood for nothing. Meyer's book is pro-ID. Everything from Nagel's reputation to his sanity was called into question.

I read the book. It felt a little like creeping behind the bike sheds at school to have a cigarette, as if an ID cancer might seize control of my synapses. The temptation was irresistible. What I discovered was an arresting book about science, which is what drew Nagel. But it is close to vacuous when it comes to the theology. That, it seems to me, is the problem with ID.

To a non-specialist like myself, Meyer seemed to capture very well the depth of the mystery that the origin of life is to modern science – essentially how DNA, as an astonishingly precise and complex information processing system, could possibly have come about. It's analogous to the monkey-bashing-at-a-typewriter-and-producing-Shakespeare problem, except that with DNA it's even more intractable: you've also got to account for how typewriters and language arose too, they being the prerequisites for the possibility of the prose, let alone the prose of the Bard.

That said, it's because of the inscrutable nature of life's origins that I found the book theologically unsatisfying. It proposes, in essence, an argument from ignorance.

The ID hypothesis Meyer conveys is, roughly, that life is, at base, an information processing system, information that is put to a highly specific purpose, and that the best explanation for the source of such a system is one that is intelligent. Only an intelligence could get the system going, as it were. It can't be put down to chance, since by massive margins there hasn't been nearly enough time since the Big Bang for the random encounters of organic compounds to form such highly specified self-replicating systems. Neither can it be put down to self-organisation, since what DNA requires to work is not general patterns, but the fantastically fine-grained and specific activity of proteins and amino acids. Intelligent design is, then, the best hypothesis to date. But that qualification, "to date", is the problem.

Eagleton and Hitchens against Nihilism

Two recent books converge on a common enemy: the bland atheist managerialism that assumes the point of life is fun.

Peter Hitchens is a Mail on Sunday columnist who writes from the right. Terry Eagleton is a professor of English literature who writes from the left. What's striking, reading their new books alongside each other – Hitchens' The Rage Against God and Eagleton's On Evil – is that they both have the same target in their sights: nihilism.

Hitchens wrote his book to unpick the arguments of his brother, Christopher, one of the big gun anti-theists, though much of it is taken up with his thoughts on why Christianity has become so marginal in Britain today. More than anything else, he puts it down to the two world wars, and the Church of England's alignment with these national causes: after all the horror and bloodshed, the pews emptied. Add to that the decline of empire, and the anxiety about what Britain now is, and the established religion inevitably declines and worries about itself too.

Hitchens also blames the rampant liberalism if his generation; he was a teenager in the 1960s. They feared the constraints of their parents" lifestyle – post-war rationing coupled to the limitations of life in the suburbs. So, they pursued life goals of unbridled ambition and pleasure, viscerally rejecting anything that smacked of authority and moral judgment. That fed the undermining of Christianity too.When it comes to his brother's blast against God, he makes a number of points. On the "good without God" question, he argues that morality must make an absolute demand on you, so that even though you constantly fail to reach its high standards, you are not able to ignore it, as he believes people and politicians now do every day: witness everything from common rudeness to the suspension of Habeas Corpus. If there are no laws that even kings must obey, no-one is safe.

His toughest rhetoric comes when he notes that the Russian communists moved remarkably swiftly to stop religious education, after they had seized power in 1917. He sees clear parallels between this move and his brother's nostalgia for Trotsky, and the argument that religious education is child abuse. "It is a dogmatic tyranny in the making," he concludes.

Incredible Views

Review of four books on atheism

Despite the recent intensification of debate between atheists and religious believers, the result still seems to be stalemate. Protagonists can readily identify their opponent's weak spots, and so delight their supporters. At the same time, both sides can fall back on their best arguments, thereby reviving their fortunes when necessary. The new atheism has created, or recovered, a perfect sport. No one can win in the game called "God"; everyone can land blows.

But is anything important or new emerging from the spat? Consider one of the tussles that is rehearsed in the books under review. It centres on the so-called anthropic argument. This is the observation of physicists that certain features in the universe appear to be uncannily "tuned" in favour of life. An anthropic principle was first proposed in 1973, and generally mocked by scientists. Stephen Jay Gould wrote that the principle was like declaring that the design of ships is finely tuned to support the life of barnacles. Since then, however, physicists have become relatively comfortable with discussing the idea. This is for at least two reasons. One is that the anthropic principle, in a weak form, makes predictions about the age of the universe that can be tested. Roughly, the universe has to be a minimal age in order to allow enough time to pass for the constituents of life - such as the element carbon - to be forged in the heart of stars. It passes that test.

Second is that the alleged tuning of the universe for life has come to be seen as quite extraordinarily fine. One demonstration of this exactitude concerns "dark energy". It forms about 70 per cent of the stuff of the known universe, and is called dark because astronomers have little idea what it is. The best candidate is the energy associated with a quantum vacuum, a phenomenon that arises from quantum physics. The important point for the anthropic argument is that it turns out that this energy would have to be "tuned" to about one part in 10120. That is a very substantial number, to say the least - way higher than the number of atoms in the visible universe. In a recent issue of the magazine Discover, the robust atheist and Nobel Prizewinning physicist Steven Weinberg described this as "the one fine-tuning that seems to be extreme, far beyond what you could imagine just having to accept as a mere accident."

Butchers and Saints

The villains of history seem relatively easy to understand; however awful their deeds, their motives remain recognizable. But the good guys, those their contemporaries saw as heroes or saints, often puzzle and appall. They did the cruelest things for the loftiest of motives; they sang hymns as they waded through blood. Nowhere, perhaps, is this contradiction more apparent than in the history of the Crusades. When the victorious knights of the First Crusade finally stood in Jerusalem, on July 15, 1099, they were, in the words of the chronicler William of Tyre, "dripping with blood from head to foot." They had massacred the populace. But in the same breath, William praised the "pious devotion . . . with which the pilgrims drew near to the holy places, the exultation of heart and happiness of spirit with which they kissed the memorials of the Lord’s sojourn on earth."

At the same time, "Holy Warriors" is what Phillips calls a "character driven" account. The book is alive with extravagantly varied figures, from popes both dithering and decisive to vociferous abbots and conniving kings; saints rub shoulders with "flea pickers." If Richard the Lion-Hearted and Saladin dominate the account, perhaps unavoidably, there are also vivid cameos of such lesser-known personalities as the formidable Queen Melisende of Jerusalem and her rebellious sister Alice of Antioch. Heraclius, the patriarch of Jerusalem, is glimpsed in an embarrassing moment when a brazen messenger announces to the assembled high court where he sits in session that his mistress, Pasque, has just given birth to a daughter.

It’s tempting to dismiss the crusaders’ piety as sheer hypocrisy. In fact, their faith was as pure as their savagery. As Jonathan Phillips observes in his excellent new history — in case we needed reminding at this late date — "faith lies at the heart of holy war." For some, of course, this will be proof that something irremediably lethal lies at the heart of all religious belief. But the same fervor that led to horrific butchery, on both the Christian and the Muslim sides, also inspired extraordinary efforts of self-sacrifice, of genuine heroism and even, at rare moments, of simple human kindness. Phillips, professor of crusading history at the University of London, doesn’t try to reconcile these extremes; he presents them in all their baffling disparity. This approach gives a cool, almost documentary power to his narrative.

The New Buddhist Atheism

A book setting out the principles of a pared-down Buddhism has won praise from arch-atheist Christopher Hitchens.

In God is Not Great, Christopher Hitchens writes of Buddhism as the sleep of reason, and of Buddhists as discarding their minds as well as their sandals. His passionate diatribe appeared in 2007. So what's he doing now, just three years later, endorsing a book on Buddhism written by a Buddhist?

The new publication is Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Its author, Stephen Batchelor, is at the vanguard of attempts to forge an authentically western Buddhism. He is probably best known for Buddhism Without Beliefs, in which he describes himself as an agnostic. Now he has decided on atheism, the significance of which is not just that he doesn't believe in transcendent deities, but is also found in his stripping down of Buddhism to the basics.

Reincarnation and karma are rejected as Indian accretions: his study of the historical Siddhartha Gautama – one element in the new book – suggests the Buddha himself was probably indifferent to these doctrines. What Batchelor believes the Buddha did preach were four essentials. First, the conditioned nature of existence, which is to say everything continually comes and goes. Second, the practice of mindfulness, as the way to be awake to what is and what is not. Third, the tasks of knowing suffering, letting go of craving, experiencing cessation and the "noble path". Fourth, the self-reliance of the individual, so that nothing is taken on authority, and everything is found through experience.

It's a moving and thoughtful book that does not fear to challenge. It will cause consternation, not least for its quietly harsh critique of Tibetan Buddhism as authoritarian. It is full of phrases that stick in the mind, such as "religion is life living itself."

Hitchens calls it "honest" and "serious", a model of self-criticism, and an example of the kind of ethical and scientific humanism "in which lies our only real hope". The endorsement makes sense because Batchelor's is an account of Buddhism for "this world alone". His deployment of reason and evidence, coupled to the imperative to remake Buddhism and hold no allegiance to inherited doctrines, would appeal to Hitchens. And not just Hitchens.

Review: 'The Hidden Brain' by Shankar Vedantam

Sen. Harry Reid has faced sharp criticism for speculating during the 2008 campaign that Barack Obama may have had an advantage as a black presidential candidate because of his light skin. But a practical test carried out by the Obama campaign -- and now revealed in Shankar Vedantam’s book, "The Hidden Brain" -- suggests that Reid may have been on target.

Near the end of the race, Democratic strategists considered combating racial bias by running feel-good television advertisements. The campaign made two versions of the same ad. One featured images of a white dad and two black dads in family settings reading "The Little Engine That Could" to their daughters. The other depicted similar scenes with a white dad and a light-skinned black dad. The first version got high ratings from focus groups, but it did not budge viewers' attitudes toward Obama. The second version elicited less overt enthusiasm, but it increased viewers' willingness to support the candidate. The spots never aired in part, Vedantam writes, because of budget problems.

Vedantam, a science reporter for The Washington Post, saw these ads in the course of his reporting on the science of the unconscious mind. The contrast between viewers' expressed sentiments and their inclinations as voters is, he argues, evidence of the unconscious in action -- in this case, through bias against dark skin. "We are going back to the future to Freud" with this application of science to politics, explains Drew Westen, a psychologist who advised the Obama campaign.

We may be heading back farther yet. Before Freud, the unconscious was understood as a social monitor. Illustrating this limited concept, Freud's collaborator, Joseph Breuer, once wrote that he would suffer "feelings of lively unrest" if he had neglected to visit a patient on his rounds. Freud proposed a more complex, creative unconscious, one that accessed forgotten facts and feelings and, using poetic logic, concocted meaningful dreams, medical symptoms and slips of the tongue. A common example of a misstep provoked by the psychoanalytic unconscious has a young man calling a woman a "breast of fresh air" and then correcting himself: "I mean, a breath of flesh air."

This clever unconscious has fallen on hard times. While contemporary research finds that mental processes occurring outside awareness shape our decisions, the unconscious revealed in those studies is stodgy. It uses simple mechanisms to warn us of risks and opportunities -- and often it is simply wrong.

The Fruitless Search for Fact

AN Wilson's 'Jesus' shows how anyone combing the gospels for history is likely to be disappointed.

The Jesus seminar is a group of scholars who have adopted a systematic approach to the search for the historical Jesus. Listing all the sayings and acts attributed to him, they colour code the likely veracity of each according to the standards of biblical criticism. For example, if the saying or act fits uneasily with subsequent Christian teaching, it's likely to be true, for only that could have stopped its suppression. One of these sayings is Jesus' injunction to turn the other cheek. An "inauthentic" saying is the beatitude he supposedly pronounced on those persecuted for following the Son of Man. The work has led the scholars to conclude that Jesus was an extraordinary ethical teacher, perhaps akin to Gandhi. It's an answer to the question of who this man was that AN Wilson, in his book "Jesus", utterly refutes.

It's not that what's recorded about him in the four gospels is not fascinating to search and weigh. Rather, it's that the ethical teaching is too muddled. Jesus has been read as a pacifist, as the saying about turning the other cheek might imply. And yet his disciples apparently carried swords in the Garden of Gethsemane. He taught that the poor would be blessed, though archaeological evidence suggests he lived for most of his life in a comfortable home. It just doesn't add up. "A patient and conscientious reading of the gospels will always destroy any explanation which we devise," Wilson writes. "If it makes sense, it's wrong."

His book is written in an open-minded, if questioning tone. He tests the evidence, whilst respecting the faith of ordinary Christians. His barbs are mostly saved for institutions like churches, who have consistently shown "contempt" towards what their supposed founder reportedly said. Some allow divorce, when Jesus is almost certain to have forbidden it. Others claim Jesus as their founder, when the fact that he didn't present his teachings in anything like a systematic form, but rather engaged with existing Jewish teaching, implies otherwise. He seems to have regarded himself as an authoritative, reformist rabbi, with apocalyptic leanings. He almost certainly believed that a new kingdom was coming, one so imminent that his disciples could live by it already.

Holier than Thou

In a letter of 1521, Martin Luther exhorted his fellow reformer Philipp Melanchthon to "be a sinner and sin strongly, but have faith and rejoice in Christ even more strongly!" The antithesis is carefully couched, suggesting a subtle dynamic between the extremes of bold sinfulness and joyful faith as though in some indefinable way they fed upon one another (and perhaps they do). Luther's words convey that tremulous equipoise of irreconcilables which has characterised Christian belief from its beginnings. In his new, massive history of Christianity, the distinguished Reformation scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch balks at such robust paradoxes. Unreason — that "faith in things unseen" — leaves him queasy. It leads to beliefs he finds preposterous. Christianity intrigues him because he cannot understand "how something so apparently crazy can be so captivating to millions of other members of my species". It inspires intolerance, bigotry, fanaticism and their murderous consequences. "For most of its existence," he writes, "Christianity has been the most intolerant of world faiths." As if this weren't bad enough, it indulges in "gender-skewed language."

Although MacCulloch purports to be writing a history for the general reader — his book was the basis for "a major BBC TV series" this autumn — his take on Christianity is highly tendentious. When he sticks to events, such as the Council of Chalcedon in 451, which provoked the first momentous schism in Christian history, or when he untangles obscure doctrinal disputes, ranging from the controversies incited by the Iconoclasts to the baffled modern clashes between genteel traditional Protestants and rowdy Pentecostals, he can be superb. His scope is enormous. His discussion of Christianity in Ethiopia is as thorough as his explorations of 19th-century American revivalist movements. And his attention to often disregarded detail is impressive. His affectionate references to devotional music, from the hymns of Charles Wesley to Negro spirituals to the old Roman Catholic service of Benediction, enliven his account. Unsurprisingly, as the author of the magisterial Reformation: Europe's House Divided 1490-1700, he is excellent on the rise of Protestantism and on the Catholic Counter-Reformation. But he's just as informed, and as informative, about recent developments, whether the Second Vatican Council or the Orthodox Church in post-Soviet Russia.

A Science Writer for the Ages

At age 95, Martin Gardner continues to churn out thought-provoking essays and reviews that are aimed squarely at pieties of all kinds.

Martin Gardner is fond of quoting the following from Isaac Newton:

"I don't know what I may seem to the world, but as to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me."

It's a statement not only of scientific (and thus human) wonder, but of scientific (and thus human) modesty. All of us, even the geniuses, as Newton assuredly was, can at best catch only partial glimmers of "the great ocean of truth."

Wading into that ocean is a pursuit that Gardner, though science writer rather than scientist (he usually refers to himself as a journalist), has been engaged in for much of his very long life. And at 95, he shows little sign of abandoning it. Gardner made himself famous as both long-time author of a Scientific American column on mathematical games and diversions and as a thoroughgoing skeptic, author of such works as Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science; published in 1952, it was among the very earliest works to debunk pseudo-science and to scold the popular press for its frequent credulity.

My own introduction to Gardner was through another branch of his interests: literature. Gardner virtually invented the now-popular genre of annotated editions of classic works and, relatively early in life, I came upon and hugely enjoyed his editions of "Alice in Wonderland" (The Annotated Alice still sits on my shelves) and Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner".

And even though he now resides in an assisted-living home in his native Oklahoma, Gardner continues to churn out essays and reviews, and collect them in books, of which "When You Were a Tadpole and I Was a Fish" is the latest.

Here you'll find book reviews and essays in several categories, including Science, Logic, Literature and Religion, all displaying Gardner's trademark erudition, expansiveness and curiosity.