Science & Religion

Why Science is More Fragile than Faith

We tend to see modernity in part as a triumph of science--an age when experimental discoveries and analysis have eclipsed religion and other ancient beliefs. And it is our scientific understanding of the world and mastery of technology that will mold the future of human affairs.

Not so fast, says Robert N. McCauley.

McCauley, a philosopher of science at Emory University, looks at the contemporary world and sees it differently: It is science, not religion, that is fragile.

In a new book, "Why Religion is Natural and Science Is Not," McCauley argues that, if you consider how the human mind actually works, science faces challenges even where it seems ascendant. Religion is too intuitive, too natural a style of thinking, to be gotten rid of.

In contrast, modern scientific thinking is radically unnatural. It is difficult to acquire as a skill, and researchers find that even people trained in science can easily revert to nonscientific thinking.

McCauley’s best-known work, the 1990 book "Rethinking Religion: Connecting Cognition and Culture," written with E. Thomas Lawson, helped start the scientific study of religious cognition, influencing or foreshadowing well-known thinkers on religion and culture such as Pascal Boyer, Daniel Dennett, and Scott Atran.

Those thinkers have tended to use evolutionary explanations of religion as a means to dismiss it, part of an increasingly fractious war over whether belief has any place in a rationalist world. McCauley himself considers the whole debate over science and religion overblown--it’s like comparing apples and sofas, he says. Even in places that seem to have abandoned religion, like Northern Europe, he questions whether there hasn’t simply been a shift toward a less-organized form of spiritual expression.

As for the unnatural world of science, he’s worried. He spoke to Ideas twice by phone; this interview was edited and condensed from those conversations.

IDEAS: Back in 1990, you and Tom Lawson pioneered the scientific study of religion, by trying to trace the cognitive basis for religion. What’s changed in the field in the last two decades?

MCCAULEY: The changes are huge! Things like social neuroscience didn’t exist in the 1980s much. There are both new tools and new findings. The most prominent tools have been those for neuroimaging. We’re seeing lots of interesting findings. Emma Cohen studied Oxford’s rowing teams. One finding she got is the guys who were rowing in synchrony have far, far higher pain thresholds, by virtue, it looks like, of their joint effort. That seems to resonate fairly closely with what we know about religion.

IDEAS: What popular ideas have emerged that are wrong?

Robert McCauley: Why Religion is Natural

(And Science is Not)

Over the last decade, there have been many calls in the secular community for increased criticism of religion, and increased activism to help loosen its grip on the public.

But what if the human brain itself is aligned against that endeavor?

That's the argument made by cognitive scientist Robert McCauley in his new book, Why Religion is Natural and Science is Not.

In it, he lays out a cognitive theory about why our minds, from a very early state of development, seem predisposed toward religious belief—and not predisposed towards the difficult explanations and understandings that science offers.

If McCauley is right, spreading secularism and critical thinking may always be a difficult battle—although one no less worthy of undertaking.

Dr. McCauley is University Professor and Director of the Center for Mind, Brain, and Culture at Emory University. He is also the author of Rethinking Religion and Bringing Ritual to Mind.

- listen… []

A Knack for Bashing Orthodoxy

Profiles in Science: Richard Dawkins

OXFORD, England —You walk out of a soft-falling rain into the living room of an Oxford don, with great walls of books, handsome art and, on the far side of the room, graceful windows onto a luxuriant garden.

Does this man, arguably the world’s most influential evolutionary biologist, spend most of his time here or in the field? Prof. Richard Dawkins smiles faintly. He did not find fame spending dusty days picking at shale in search of ancient trilobites. Nor has he traipsed the African bush charting the sex life of wildebeests.

He gets little charge from such exertions.

"My interest in biology was pretty much always on the philosophical side," he says, listing the essential questions that drive him. "Why do we exist, why are we here, what is it all about?"

It is in no fashion to diminish Professor Dawkins, a youthful 70, to say that his greatest accomplishment has come as a profoundly original thinker, synthesizer and writer. His epiphanies follow on the heels of long sessions of reading and thought, and a bit of procrastination. He is an elegant stylist with a taste for metaphor. And he has a knack, a predisposition even, for assailing orthodoxy.

In his landmark 1976 book, "The Selfish Gene," he looked at evolution through a novel lens: that of a gene. With this, he built on the work of fellow scientists and flipped the prevailing view of evolution and natural selection on its head.

He has written a string of best sellers, many detailing his view of evolution as progressing toward greater complexity. (His first children’s book, "The Magic of Reality," appears this fall.) With an intellectual pugilist’s taste for the right cross, he rarely sidesteps debate, least of all with his fellow evolutionary biologists.

When Is It Ramadan?

An Arab Astronomer Has Answers.

This week will see the start of the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, a time when hundreds of millions of Muslims around the globe devote themselves to fasting and prayer. But to Algerian scientist Nidhal Guessoum, a Sunni Muslim, it's also a time of chaos—and "an embarrassment" to Islam.

Tradition dictates that Ramadan, like other holy months in the Islamic calendar, begins the day after the thin crescent of the new moon is first seen with the naked eye. Because visibility is very dependent on local atmospheric conditions, religious officials in different countries—relying on eye-witness observations from volunteers—often disagree on the exact moment, sometimes by as much as 3 or 4 days. It's a recipe for international confusion.

Guessoum, an astrophysicist at the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates, is one of the most high-profile advocates of a scientific approach to the problem that would end the confusion. Its adoption would not only help Muslims plan their lives—"I need to know whether I can hold a meeting on August 30," Guessoum says—but also be a sign that Muslim countries, once at the forefront of science, are again "able to integrate science into social and cultural life," he says.

Guessoum, the vice president of an international organization known as the Islamic Crescents' Observation Project (ICOP), believes science can help solve other practical problems in the Muslim faith. In frequent TV appearances, public lectures, blog posts, and books, he has explained how astronomical techniques can help determine prayer times in countries far from the equator or establish the direction of Mecca.

His attempts to apply science to Islamic rituals has earned him respect, but they have also ruffled the feathers of religious conservatives. So has his support for biological evolution and his rejection of claims that the Koran anticipated much of modern science. He can make people without much scientific knowledge "uneasy," says Zulfiqar Ali Shah, an influential U.S. cleric who supports his ideas about the Islamic calendar. When dealing with religious scholars, Guessoum "is very respectful but forceful," Ali Shah adds.

Guessoum, 50, obtained a physics degree in Algeria in 1982. He earned a Ph.D. in theoretical astrophysics at the University of California, San Diego, after which he spent 2 years at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, working on gamma ray astrophysics, which is still the focus of his research. A "moral and financial duty" to pay back for his education made him return to Algeria in 1990. There, ordinary people and religious officials often asked him to explain the science of crescent sighting, a topic that astronomer Bradley Schaefer, now at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, had got him interested in. He published a book on the topic in Arabic in 1997.

Science is the Only Road to Truth? Don't Be Absurd.

Overvaluing science leads to illogicality, as a Nobel prize winner has proved.

By the standards of very clever men who believe some very silly things, Harry Kroto is a quite unremarkable scientist. Unlike some other Nobel prize winners, he is not an enthusiastic Nazi, a Stalinist, a eugenicist, or even a believer in ESP. He did play a prominent, and I think disgraceful part in the agitation to have Michael Reiss sacked from a job at the Royal Society for being a priest. But the video of his speech at the Nobel laureates meeting this year in Lindau, Austria, is something else. Much of it is great stuff about working for love, not money; and about the importance of art, but around eight minutes in he goes off the rails. First there is a slide saying (his emphases): "Science is the only philosophical construct we have to determine TRUTH with any degree of reliability." Think about this for a moment. Is it a scientific statement? No. Can it therefore be relied on as true? No.

But formal paradoxes have one advantage well known to logicians, which is that you can use them to prove anything, as Kroto proceeds to demonstrate. Or, as he puts it: "Without evidence, anything goes." Remember, he has just defined truth (or TRUTH) as something that can only be established scientifically. So nothing he says about ethics or intellectual integrity after that need be taken in the least bit seriously. It may be true, but there is no scientific way of knowing this and he doesn't believe there is any other way of knowing anything reliably.

Note how this position completely undermines what he then goes on to say – that "the Ethical Purpose of Education must involve teaching our young people how they can decide what they are being told is true" (his caps). Again, this is not a scientific statement, and therefore cannot, on Kroto's terms, be a true one.

The Priest-Physicist Who Would Marry Science to Religion

John Polkinghorne leads a disparate group of scientists on the controversial search for God within the fractured logic of quantum physics.

When he describes his line of work, John Polkinghorne jests, he encounters "more suspicion than a vegetarian butcher." For the particle physicist turned Anglican priest, dissonance comes with the territory. Science parses the concrete: the structure of the atom and the workings of the brain. Religion confronts the intangible: questions about ethics and the purpose of life. Taken literally, the biblical story of Genesis contradicts modern cosmology and evolutionary biology in full.

Yet 21 years ago, in a move that made many eyes roll, Polkinghorne began working to unite the two sides by seeking a mechanism that would explain how God might act in the physical world. Now that work has met its day of reckoning. At a series of meetings at Oxford University last July and September, timed to celebrate Polkinghorne’s 80th birthday, physicists and theologians presented their answers to the questions he has so relentlessly pursued. Do any physical theories allow room for God to influence human actions and events? And, more controversially, is there any concrete evidence of God’s hand at work in the physical world?

Sitting with Polkinghorne on the grounds of St. Anne’s College, Oxford, it is difficult to regard the jovial gentleman with suspicion. Oxford has been dubbed the "city of dreaming spires," and Polkinghorne is as quintessentially English as the university’s famed architecture, with college towers and church spires standing side by side. The bespectacled elder statesman of British science walks with a stick and wears hearing aids in both ears. But he retains a spring in his step and a quick wit. ("He will charm you in conversation, as long as you get him in his better ear," a colleague says.)

Polkinghorne’s dual identity emerged early. He grew up in a devout Christian family but was always drawn to science, and in graduate school he became a particle physicist because, he explains modestly, he was also "quite good at mathematics." His scientific pedigree is none too shabby. He worked with Nobel laureate Abdus Salam while earning a doctorate in theoretical physics from Cambridge University, where he later held a professorial chair. One of his students, Brian Josephson, went on to win a share of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1973. Polkinghorne himself joined Nobel laureate Murray Gell-Mann in research that led to the discovery of the quark, the building block of atoms. But in 1979, after 25 years in the trenches, Polkinghorne decided that his best days in physics were behind him. "I felt I had done my bit for the subject, and I’d go do something else," he says. That is when he left his academic position to be ordained.

The Science of Why We Don't Believe Science

How our brains fool us on climate, creationism, and the vaccine-autism link.

"A MAN WITH A CONVICTION is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point." So wrote the celebrated Stanford University psychologist Leon Festinger [1] (PDF), in a passage that might have been referring to climate change denial—the persistent rejection, on the part of so many Americans today, of what we know about global warming and its human causes. But it was too early for that—this was the 1950s—and Festinger was actually describing a famous case study [2] in psychology.

Festinger and several of his colleagues had infiltrated the Seekers, a small Chicago-area cult whose members thought they were communicating with aliens—including one, "Sananda," who they believed was the astral incarnation of Jesus Christ. The group was led by Dorothy Martin, a Dianetics devotee who transcribed the interstellar messages through automatic writing.

Through her, the aliens had given the precise date of an Earth-rending cataclysm: December 21, 1954. Some of Martin's followers quit their jobs and sold their property, expecting to be rescued by a flying saucer when the continent split asunder and a new sea swallowed much of the United States. The disciples even went so far as to remove brassieres and rip zippers out of their trousers—the metal, they believed, would pose a danger on the spacecraft.

Festinger and his team were with the cult when the prophecy failed. First, the "boys upstairs" (as the aliens were sometimes called) did not show up and rescue the Seekers. Then December 21 arrived without incident. It was the moment Festinger had been waiting for: How would people so emotionally invested in a belief system react, now that it had been soundly refuted?

The Mythical Sam Harris

Sam Harris, one of the loudest New Atheists, has built a morality on a home-made myth and calls it scientific.

To open with a nerd joke: religion is like Unix in that those who do not understand it are compelled to reinvent it, badly. Watching Sam Harris at a packed Kensington Town Hall last night, it was obvious that he fits squarely into the American tradition of religious leaders who preach liberation from religion into something they call science. He is Mary Baker Eddy for the 21st century.

He was jet-lagged, which may account for some of the incoherence of his position, but he's a very practised performer, and has presumably given this speech hundreds of times before.

What he wants to do is to establish that moral facts exist, and that the division between fact and value is not absolute. This is hardly earth-shaking and certainly not original. Nobody was arguing against it, either on the podium or on the floor: when a show of hands was taken at the beginning of the evening, perhaps a dozen out of at least 1,000 hands went up. The difficulty, of course, comes in establishing what moral facts actually are. This Harris assumes is something to be solved by utilitarian calculation. Understandably he skips over any effort to explain or justify this assumption by argument. Instead he uses a myth.

Consider, he says, "the worst possible misery for everyone". This is a factual state which surely involves a moral obligation to diminish it. So everything which moves away from that, in the long term, is objectively good. And everything which tends to move the world closer to that state is objectively bad.

The obvious retort to this is that our judgements about the way things are tending must involve an element of faith which is something that in other contexts Harris has hoped to escape. But there is a deeper and perhaps less obvious snag.

Martin Rees's Templeton Prize May Mark a Turning Point in the "God Wars"

Awarding the Templeton prize to Rees suggests science is rejecting the advocacy of the likes of Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins – author of The God Delusion and theorist of the selfish gene – could claim to be the most famous scientist in Britain. Sir Martin Rees – astronomer royal, former president of the Royal Society, master of Trinity College, Cambridge – is arguably the most distinguished.

Last year, Dawkins published an ugly outburst against the softly spoken astronomer, calling him a "compliant Quisling" because of his views on religion. And now, Rees has seemingly hit back. He has accepted the 2011 Templeton prize, awarded for making an exceptional contribution to investigating life's spiritual dimension. It is worth an incongruous $1.6m.

Dawkins is no stranger to pungent rhetoric when it comes to religion. But "Quisling" is strong even by his standards. It was originally hurled against fascist collaborators during the second world war. Rees, a collaborator? What was the crime that warranted such approbation? The Royal Society lent its prestige to the Templeton Foundation by hosting events sponsored by the fund, which supports a variety of projects investigating the science of wellbeing and faith.

Dawkins and Rees differ markedly on the tone with which the debate between science and religion should be conducted. Dawkins devotes his talents and resources to challenging, questioning and mocking faith. Rees, on the other hand, though an atheist, values the legacy sustained by the church and other faith traditions. He confesses a liking for choral evensong in the chapel of Trinity College. It seems a modest indulgence. The ethereal voices of rehearsing choristers can literally be heard from his front door. But for Dawkins this makes the man a "fervent believer in belief". And that is a foul betrayal of science.

I should declare an interest here, as I too would be what Dawkins calls an "accommodationist", (when he is being polite). I often write about the relationship between science and religion, and have been a Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Fellow, the beneficiary of a first-rate seminar programme organised by Cambridge academics, funded by the Templeton Foundation. But then I love the big questions.

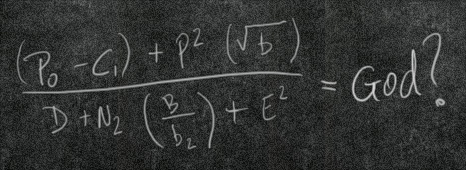

What Would "Evidence" for God Look Like?

University of Chicago biologist Jerry Coyne was inspired by a recent discussion between Richard Dawkins and A. C. Grayling to defend the notion that there could be scientific evidence that might persuade him to believe in God. Coyne has tangled in the past with other atheists among the science bloggers who on a-priori grounds dismiss any such possible evidence.

Maybe I’m foolish or credulous, but I continue to claim that there is some evidence that would provisionally—and I emphasize that last word—make me believe in a god. (One can always retract one’s belief if the god evidence proves to be the work of aliens, or of Penn and Teller). I agree, of course, that alternative explanations have to be ruled out in a case like this, but remember that many scientists have accepted hypotheses as provisionally true without having absolutely dismissed every single alternative hypothesis. If a violation of the laws of physics is observed, that would be telling, for neither aliens nor human magicians can circumvent those laws.

While I agree with Coyne, there are good philosophical reasons traditional theists would offer for not expecting to be able to find scientific evidence either. But that’s opening up a can of worms. Grayling soon responded.

What I’d like to entertain is a thought experiment that might offer the kind of evidence, or at least data, to make a skeptic take a second look.

Here is a scenario I’ve adopted from an idea that New Testament scholar Ben Witherington used in a recent novel. In terms of evidence for God it’s much less fanciful than a being accompanied by angels descending from the sky in view of hundreds of people, but:

An archeologist working in Israel, discovers an ossuary from the NT era: the inscription on the stone in Aramaic reads: "Twice dead under Pilatus; Twice born of Yeshua in sure hope of resurrection." And the name corresponds to what in Greek would be Lazarus.

Uncertainty's Promise

Whether with science or religion, only by embracing doubt can we learn and grow.

We live in an age intolerant of doubt. Communicating uncertainty is well nigh impossible across fields as diverse as politics, religion and science. There's a fear of doubt abroad too. It's most palpable, at the moment, whenever there's news of economic uncertainty. Waves of nervousness ripple through financial markets and supermarkets alike. And yet, at the same time, few would deny that only the fool believes the future is certain. And who doesn't fear that most shadowy figure of our times, the fundamentalist – with their deadly, steadfast convictions?

The confusion is understandable. Doubt is unsettling. It's not for nothing that old maps inscribed terra incognita with the words "here be dragons". Further, the tremendous success of science, and the transformation of our lives by technology, screens us from many of the troubling uncertainties that our ancestors must have been so practised in handling.

But are we losing what might be called the art of doubt too? For, in truth, without doubt there is no exploration, no creativity, no deepening of our humanity – which is why the individual who claims to know something beyond all doubt is a person to shun, not emulate. Stick to what you know and you'll find some security, but you'll also find yourself stuck in a rut. Learn to welcome the unknown, to embrace its thrill, and new worlds might open up before you.

My old physics tutor, Carlos Frenk, is an excellent case in point. He is one of the world's leading researchers on dark matter – as is advertised by a large poster that hangs outside his office. It is inscribed with five bold words: "Dark Matter – Does It Exist?" To put it another way, Professor Frenk has forged a career out of navigating the terra incognita of the cosmos. He believes there is dark matter. It makes sense of the way visible matter in the universe hangs together. But there are no guarantees. Moreover, that's a fact that his peers ache to exploit. They seek to falsify his thesis, a negative process by which they hope to prove him wrong. That's what you have to live with when your expertise is on what's uncertain. And yet, Professor Frenk remains persistently sanguine. Falsity is the only certainty in science, he tells me. Science is organised doubt. It's only when scientists can no longer say no to a thesis that it stands.

How Much Should Science Accommodate Religion

Find a public debate about the intersection of science and religion and you also can expect to find PZ Myers, a biology professor at the University of Minnesota Morris.

This month, Myers debated author Chris Mooney over questions of how far science should go to accommodate religion and whether those who champion science must oppose faith.

The debate, reported by Discover Magazine, came at a conference of the Council for Secular Humanism in Los Angeles. It continued in a special episode of Point of Inquiry, a podcast sponsored by the Center for Inquiry, where Mooney is one of three hosts.

It’s no surprise that Myers was unyielding. He has been associated with the movement called New Atheism in which authors such as Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens argue that many religious claims — including the virgin birth of Jesus — are scientific in nature and thus, like other hypotheses, can be tested and proven false.

"Talking about accommodating ourselves to others’ ideas is fine in a political and diplomatic sense, but there are core issues that we are not going compromise on," he said. "Foremost, we think religion is false."

But Myers allowed some room for framing certain relevant conversations.

"I’ve talked to fundamentalists, and often one big issue is they want to send their kids to college, they want them to succeed in this economy, and they feel really, really frightened by the fact that they’ll go off to college and be converted to godless atheists," he said. "What I will say to them is I am not going to compromise. I am an atheist. But when I teach classes....I’m too busy teaching biology to talk about this other stuff."

Mooney also is a self-described atheist and a critic of science illiteracy. He is the author of three books: The Republican War on Science, Storm World, and Unscientific America. But he differs considerably from Myers in that he argues for accommodation, or accepting a place for religious faith in scientific inquiry.

Religion is vastly diverse across America, Mooney argued. And many faiths allow varying degrees of compatibility with science.

"You will have actual Christians who, nevertheless, are supportive of the teaching of evolution, embryonic stem cell research and all of the rest," he said. "There are Christian ministers who certainly have Christian beliefs [who] say evolution is good science and it’s OK to have this....What do we do with them?"

listen now or download Point of Inquiry Debate

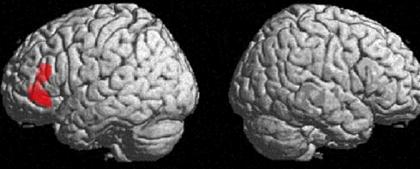

Spiritual Science, Rational Morality

Rethinking the Divide between Science and Religion

The atheist Sam Harris has just lobbed a bombshell into the roiling debate over science and religion. In his new book The Moral Landscape, he argues for an entirely new understanding of morality, based not on religion but on new insights from science, especially brain science. Harris, a neuroscientist himself, is out to demolish the idea that science is by definition a value-free space. "The split between facts and values - and, therefore between science and morality - is an illusion," he writes. "Science has long been in the values business." He believes science and rationality provide a far better foundation for moral guidance than tired prescriptions from religion.

Harris' book comes on the heels of Stephen Hawking's recent assault on religion and philosophy. His claim that "the universe can and will create itself out of nothing" -- without God's intervention -- sparked a predictable furor. But even more provocative is Hawking's assertion that science can finally answer some of the great existential questions: Why is there something rather than nothing? And why do we exist? As Hawking and fellow physicist Leonard Mlodinow write in their book The Grand Design, "Traditionally, these are questions for philosophy, but philosophy is dead." Why? Because it hasn't kept up with modern developments in science, particularly physics.

For centuries, philosophers and theologians have presided over these questions about values and purpose, but scientists such as Harris and Hawking are no longer willing to cede this territory to religion. The cutting edges of science -- from cosmology and evolutionary biology to neuroscience -- are now tackling the most profound questions of our existence. Even the soul is under scientific scrutiny. Or at least the soul as it's defined by modern science: the self-aware mind with its keen sense of morality and free will.

Is this scientific overreach? The late biologist Stephen Jay Gould certainly thought so. In his 1999 book Rocks of Ages, he tried to broker a truce between science and religion by claiming they are two utterly distinct realms of understanding, what he called "nonoverlapping magisteria" (NOMA). Science, according to Gould, covers the empirical world of fact and theory, while questions about moral meaning and value fall within the religious realm. This attempt to divide the world between fact and meaning has shaped the discussion of science and religion, but we're now moving beyond Gould's dichotomy.

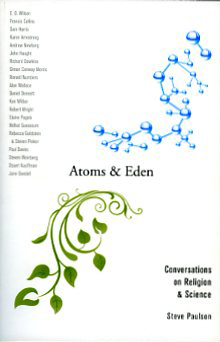

Atoms and Eden

Conversations on Religion and Science

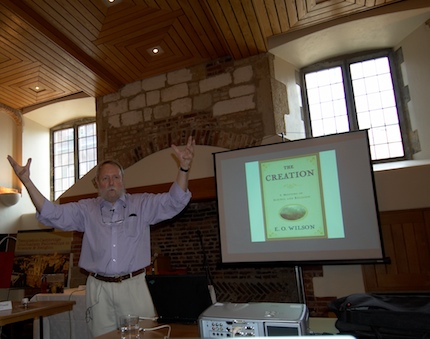

Here is an unprecedented collection of twenty freewheeling and revealing interviews with major players in the ongoing--and increasingly heated--debate about the relationship between religion and science. These lively conversations cover the most important and interesting topics imaginable: the Big Bang, the origins of life, the nature of consciousness, the foundations of religion, the meaning of God, and much more.

In Atoms and Eden, Peabody Award-winning journalist Steve Paulson explores these topics with some of the most prominent public intellectuals of our time, including Richard Dawkins, Karen Armstrong, E. O. Wilson, Sam Harris, Elaine Pagels, Francis Collins, Daniel Dennett, Jane Goodall, Paul Davies, and Steven Weinberg. The interviewees include Christians, Buddhists, Jews, and Muslims, as well as agnostics, atheists, and other scholars who hold perspectives that are hard to categorize. Paulson's interviews sweep across a broad range of scientific disciplines--evolutionary biology, quantum physics, cosmology, and neuroscience--and also explore key issues in theology, religious history, and what William James called ''the varieties of religious experience.''

Collectively, these engaging dialogues cover the major issues that have often pitted science against religion--from the origins of the universe to debates about God, Darwin, the nature of reality, and the limits of human reason. These are complex, intellectually rich discussions, presented in an accessible and engaging manner. Most of these interviews were originally published as individual cover stories for Salon.com , where they generated a huge reader response. Public Radio's "To the Best of Our Knowledge" will present a major companion series on related topics this fall.

A feast of ideas and competing perspectives, this volume will appeal to scientists, spiritual seekers, and the intellectually curious.

New Atheism or Accommodation?

Recently at the 30th anniversary conference of the Council for Secular Humanism in Los Angeles, leading science blogger PZ Myers and Point of Inquiry host Chris Mooney appeared together on a panel to discuss the questions, "How should secular humanists respond to science and religion? If we champion science, must we oppose faith? How best to approach flashpoints like evolution education?"

It's a subject about which they are known to... er, differ.

The moderator was Jennifer Michael Hecht, the author of Doubt: A History. The next day, the three reprised their public debate for a special episode of Point of Inquiry, with Hecht sitting in as a guest host in Mooney's stead.

This is the unedited cut of their three way conversation.

PZ Myers is a biologist at the University of Minnesota-Morris who, in addition to his duties as a teacher of biology and especially of development and evolution, likes to spend his spare time poking at the follies of creationists, Christians, crystal-gazers, Muslims, right-wing politicians, apologists for religion, and anyone who doesn't appreciate how much the beauty of reality exceeds that of ignorant myth.

Jennifer Michael Hecht is the author of award-winning books of philosophy, history, and poetry, including: Doubt: A History (HarperCollins, 2003); The End of the Soul: Scientific Modernity, Atheism and Anthropology (Columbia University Press, 2003); and The Happiness Myth, (HarperCollins in 2007). Her work appears in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Republic, and The New Yorker. Hecht earned her Ph.D. in History from Columbia University in 1995 and now teaches in the graduate writing program of The New School University.

- listen… []

Cosmology, Cambridge Style: Wittgenstein, Toulmin, and Hawking

Hawking Said, "Let There Be No God!," and There was Light!

Hawking Said, "Let There Be No God!," and There was Light!

That headline flashed to all corners of the media universe this month. Of course, we don't know whether a universe has corners. Truth is, we don't know much about the universe that isn't astonishingly inferential. Alas, you'd hardly know that from listening to the retired Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge and his media echo chamber.

The breaking news originated in the latest book by Stephen Hawking, The Grand Design (Bantam), co-written with physicist Leonard Mlodinow. It excited front-page editors as few science tomes do. Britain's Mirror exclaimed, "Good Heavens! God Did Not Create the Universe, Says Stephen Hawking." Canada's National Post drolly chimed in with, "In the Beginning, God Didn't Have to Do a Thing."

In his new book, Hawking, the celebrated author of A Brief History of Time (Bantam, 1988), declares on the first page that "philosophy is dead" because it "has not kept up" with science, which alone can explain the universe. "It is not necessary to invoke God," the authors write, "to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going." Hawking sound-bited the hard stuff for interviewers: "Science makes God unnecessary," he told Good Morning America. Something simply came out of nothing.

If you've followed the science-religion debate in recent times, there's nothing new about such claims. Many scientists take Hawking's side, some do not. Almost everyone agrees that, as Hawking told ABC News, "One can't prove that God doesn't exist." The Templeton Foundation, which specializes in prodding believers and nonbelievers to discuss such things in civilized ways, has published all sorts of booklets, like "Does Science Make Belief in God Obsolete?," in which some eminent scientists answer "Yes" and others answer "No."

Why, then, the uproar? Largely because Hawking has been anointed by the media as possibly "the smartest man in the world" (ABC News) and the "most revered scientist since Einstein" (The New York Times)—a genius, and so on. A genius, presumably, must be right about everything. Especially if he managed to sell nine million copies of a book.

Hawking's latest claims also sparked attention because A Brief History of Time ended with his observation that, if we could achieve a unified theory in physics, we would "know the mind of God." While Hawking's fellow atheists took that coda as a play on Einstein's earlier use of the phrase, many believers chose to read it as open-mindedness toward a possible creator, making this new book a sharp U-turn.

Harvest Moons and the Seeds of Our Faith

How the fall equinox, and the science of ancient astronomy, helped shape religions.

Next Wednesday heralds the official end of summer—the autumnal equinox —when the length of day and night are equal (circa 11:09 p.m. ET). In the 21st century, this astronomical event is little more than a passing curiosity. But rewind by about three millennia to the time of the ancient Babylonians, and the autumnal equinox marked the start of the "minor new year." Not only did celestial events define sacred festivals. Conversely, religion powered the development of astronomy, the first science.

Today, science and religion are often thought to be very different, unconnected disciplines. But looking back at our ancient past, we see that the development of religion and early science have really gone hand-in-hand, shaping some of the characteristics of mainstream religion in ways we may not realize.

For instance, while the Babylonians celebrated their "main new year" in the spring, their tradition of having a minor autumnal new year has carried over into both mainstream religion and secular practice. Nick Campion, a historian of cultural astronomy at the University of Wales, notes two echoes of ancient autumn observances today. "It's a custom inherited by Jews—hence Rosh Hashanah," he told me, "while the beginning of the academic year in autumn is a secular legacy."

The Babylonians made meticulous records of celestial events. To them, as to many ancient civilizations, the sky was thought to be the writing pad of the gods, while the stars and planets were the ink used to communicate divine messages.

Through today's lens, the practices of star-gazing Babylonian priests may appear to be based mostly in superstition. Each night they searched the sky for omens sent by the great god Marduk or one of his entourage of lesser deities. Unexpected wanderings of the planets might foreshadow a poor harvest in the village, while the early risings of the moon could portend malformed births. By far the worst harbinger was a lunar eclipse, which signaled that the gods were angry with the king and called for his death.

Much early astronomy dealt with developing techniques to predict these omens, allowing crucial time for pre-emptive prayers and rituals to ward off misfortune.

Despite being tied to religious ritual (and often to gruesome sacrifice), the work of these priests marks the beginnings of science, says John Steele, a historian of ancient astronomy at Brown University. "They were making mathematical predictions based on empirical observations, which is astronomy by definition," he says.

Spirituality Can Bridge Science-Religion Divide

We hear a lot these days about the "conflict" between science and religion — the atheists and the fundamentalists, it seems, are constantly blasting one another. But what's rarely noted is that even as science-religion warriors clash by night, in the morning they'll see the battlefield has shifted beneath them.

Across the Western world — including the United States — traditional religion is in decline, even as there has been a surge of interest in "spirituality." What's more, the latter concept is increasingly being redefined in our culture so that it refers to something very much separable from, and potentially broader than, religious faith.

Nowadays, unlike in prior centuries, spirituality and religion are no longer thought to exist in a one-to-one relationship.

This is a fundamental change, and it strongly undermines the old conflict story about science and religion. For once you start talking about science and spirituality, the dynamic shifts dramatically.

Common ground

The old science-religion story goes like this: The so-called New Atheists, such as Richard Dawkins, uncompromisingly blast faith, even as religiously driven "intelligent design" proponents repeatedly undermine science. And while most of us don't fit into either of these camps, the extremes also target those in the middle. The New Atheists aim considerable fire toward moderate religious believers who are also top scientists, such as National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins. Meanwhile, people like Collins get regular flack from the "intelligent design" crowd as well.

In this schematic, the battle lines may appear drawn, the conflict inescapable. But once spirituality enters the picture, there seems to be common ground after all.

Spirituality is something everyone can have — even atheists. In its most expansive sense, it could simply be taken to refer to any individual's particular quest to discover that which is held sacred.

That needn't be a deity or supernatural entity. As the French sociologist Emile Durkheim noted in 1915: "By sacred things one must not understand simply those personal beings which are called Gods or spirits; a rock, a tree, a spring, a pebble, a piece of wood, a house, in a word, anything can be sacred."

Something Rather Than Nothing

The scientists who find space for religion

Not all scientists share Stephen Hawking’s view that modern physics makes the Creator redundant, writes Edwin Cartlidge.

Among these is John Polkinghorne of Cambridge University, who is well known for his studies on the relationship between science and religion, having worked as a particle physicist for 25 years before becoming ordained in the Church of England. Polkinghorne says his religious belief does not spring from one "knockdown argument" for the existence of God but instead derives from a number of different sources. Among these are personal experience, including worship and reflecting on the decisions he has taken in life. But he also draws faith from the very fact that the universe is intelligible and describable in terms of mathematics, and that the laws of nature appear to be finely tuned to support life. This observation he believes is more satisfactorily explained by the existence of God than the possibility of countless parallel universes – among which one is bound to be suited to life – or simply the brute fact of existence.

Polkinghorne finds much common ground with nuclear physicist and theologian Ian Barbour of Carleton College in the US, including the belief that both science and religion seek to explain an objective reality that cannot be understood in a straightforward way. But Polkinghorne has a more traditional view of Christ than Barbour, believing that Christ was both fully human and fully divine, that he was born of a virgin and that he was resurrected. Indeed, Polkinghorne believes there is both good historical evidence and strong theological motivation for the Resurrection. Barbour, however, disputes both the reality of the empty tomb and the virgin birth.

The ‘Messy’ God of Science

A recent conference at Oxford brought scientist-theologians together to discuss the work of John Polkinghorne.

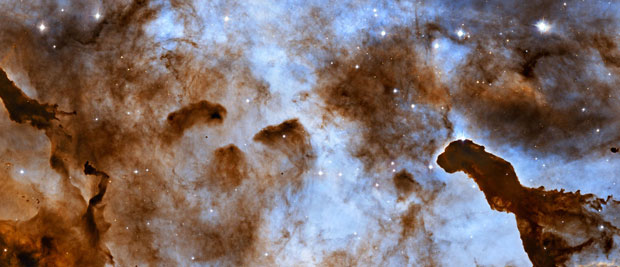

The department of physics in the University of Oxford is a hodgepodge of buildings, old and new. In a warren of rooms, its scientists pursue interests from quantum computing to theoretical cosmology. The diversity says much. As a tree of knowledge, modern physics has branches that shoot off in all directions.

Just opposite the department stands a very different building: Keble College. Its unified, gothic structure is unforgettable—built in polychromatic brick, sometimes referred to as the ‘holy zebra’ style. The ‘holy’ refers to the college’s Victorian founder, John Keble, who is famous for spearheading the Catholic revival in the Church of England.

Today, Keble College appears to gaze across the road at its neighbor, as if musing on what science has done to religion. So the lecture theaters of the physics department were an excellent place to host a conference on that very subject, celebrating and critiquing the work of John Polkinghorne, one of the best known scientist-theologians of our times.

For the first part of his career, Polkinghorne was a mathematical physicist, rising to the position of professor in the University of Cambridge. Then, in 1979, he resigned his chair, and trained to become an Anglican priest. In the quarter century since, he has written about two dozen books on the relationship between science and religion. A delightful man to meet, between papers and presentations he talked quite as easily with humble journalists as with distinguished peers.

Polkinghorne describes himself as a ‘bottom-up’ theologian. He is concerned to show not only that modern science is compatible with orthodox Christian belief, but that the believer can have as rational a basis for their commitment as the scientist has for theirs. He borrows a notion put forward by the philosopher Michael Polanyi, of well-motivated belief, which seeks: "a frame of mind in which I may hold firmly to what I believe to be true, even though I know it may conceivably be false."

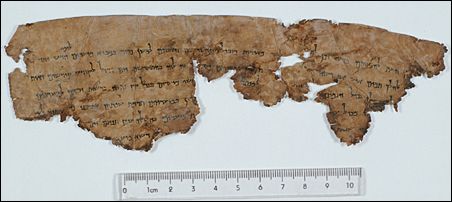

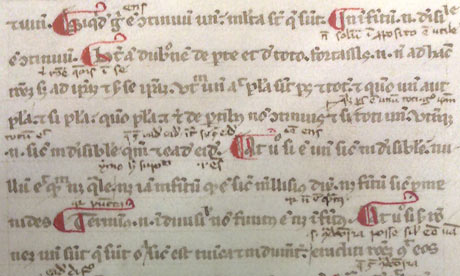

High-Tech Test of Dead Sea Scrolls

Under way at Science Museum of Minnesota

Since 1947, when a shepherd searching caves near the Dead Sea discovered fragments of ancient texts, scholars have sought ways to study the remarkable discovery — now known as the Dead Sea Scrolls — without damaging the 2,000-year-old documents. That quest continued in St. Paul on Tuesday when delegates from the Israel Antiquities Authority tested a new digital infrared camera system at the Science Museum of Minnesota.

Images in different wavelengths

In a secured and climate-controlled room at the museum, Tania Treiger used her gloved hands and assorted instruments to carefully arrange fragments of the priceless scrolls under an overhead camera. She is a conservator from Israel, one of only three people in the world who are trained and authorized to handle the ancient documents.

When the fragments were ready, overhead lights went out. Equipment beeped. Lights flickered in eerie shades. More beeps. Lights on.

Images of the fragment had been captured in 11 different wavelengths — some for reproductions in the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visible to humans and some in the infrared, said Gregory Bearman.

Bearman, a former scientist for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, has pioneered the application of imaging techniques used to observe objects in space to the study of archeological artifacts. He had arranged for a company called MegaVision to demonstrate its new imaging system for possible use with the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Did Jesus Die?

This film investigates the variety of stories surrounding the New Testament account of the crucifixion, death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus, by interviewing historians, theologians and historical researchers. This exploration of the latest theories about what really happened to Jesus 2000 years ago uncovers some surprising possibilities.

At the heart of the mystery is the suspicion that Jesus might not actually have died on the cross. The film concludes that it was perfectly possible to survive crucifixion in the 1st Century – there are records of people who did. But if Jesus survived, what happened to him afterwards?

One of the most remarkable stories concerns the charismatic preacher Jus Asaf (Leader of the Healed) who arrived in Kashmir in around 30 AD. Just before he died at the age of 80, Jus Asaf claimed that he was in fact Jesus Christ and the programme shows his tomb, next to which are his carved footprints which bear the scars of crucifixion.

Fine-Tuning the Universe

Physicists and theologians gathered in Oxford last week to discuss the complex relationship between their two disciplines, and to pay tribute to physicist and priest the Revd Dr John Polkinghorne. But in doing so, some also posed challenges to his thinking.

'Epistemology models ontology" is one of the Revd Dr John Polkinghorne’s favourite phrases. It means, roughly speaking, that what we know is a reliable guide to what is actually out there in the world. In fact, he used to say it so often that his wife gave him a T-shirt with the words emblazoned upon it. It was in the same spirit that staff from the Ian Ramsey Centre for Science and Religion at the University of Oxford tried unsuccessfully to find a T-shirt with another of Dr Polkinghorne’s trademark expressions, "bottom-up thinker", ahead of a four-day conference being held at the centre last week to mark Dr Polkinghorne’s eightieth birthday later this year.

Bottom-up thinking is central to Dr Polkinghorne’s view of reality. He carried out research in particle physics for nearly 25 years before quitting academia and training for the Anglican priesthood. Then, after serving as a parish priest for several years, he returned to the academic fold to become president of Queens’ College, Cambridge, and to investigate the interplay between science and religion.

He says that his work as a scientist showed him the importance of experience as a guide to what is true, rather than assuming that the world will conform to certain preconceived abstract principles. He maintains that the core of modern physics – quantum mechanics – with its strange, probabilistic conception of nature, would never have been dreamed up from scratch but instead came about because experimental results demanded it.

For Dr Polkinghorne, this way of thinking applies equally to theology. He argues that it is mistaken to try to prove that God exists using pure logic since, as he puts it, "clear and certain ideas often turn out to be neither clear nor certain". Indeed, he says, there is no "knockdown argument" for the existence of God. Rather, his religious belief derives from a number of different sources. These include his experience of worship and a reflection on the decisions he has taken in his life, as well as his belief in the Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

In addition, Dr Polkinghorne draws on a couple of general observations he can make as a scientist. One of these is simply the very intelligibility of the universe, the fact that it is possible to make theories about the way the world works and to use mathematics as the language of those theories, an ability which, he claims, could not have come about through mere evolutionary necessity.

Chaos Theory and Divine Action

Physicist John Polkinghorne is often accused of offering up a God-of-the-gaps argument. But his work has subtler shades.

The question: Can science explain everything?

Whether or not science can explain everything is a question that was never far from the minds of a large group of theologians and scientists who met in Oxford last week. They'd assembled to celebrate the 80th birthday of John Polkinghorne, the professor of mathematical physics who made his name for his work on quarks, now an Anglican priest, and author of many books on science and religion. Moreover, it turns out that the question of science's limitations is intimately linked to Polkinghorne's much misunderstood account of God's action in the world.

The challenge is to avoid concocting a "God of the gaps" – a deity whose action occurs in the gaps where scientific explanations apparently fall short. The best known example of this is probably the bacterial flagellum. Advocates of intelligent design have argued that these whip-like devices for locomotion can only be explained by divine intervention because of their supposed "irreducible complexity". The trouble is that science progresses. What can't be explained in one decade is often explained in the next. Gaps get filled, and so God gets squeezed out.

Polkinghorne has been accused of advocating a God-of-the-gaps approach too. He has been taken to argue that chaos theory offers a way of understanding divine action, by virtue of the mistaken assumption that chaos theory paints a picture of an indeterminate world: if it's impossible to forecast the weather next week with any degree of accuracy, then perhaps that points to a pervasive randomness in the physical world, which God might exploit to divine advantage.

But that's not his idea, as Nick Saunders pointed out at the conference. As Polkinghorne knows better than most, the equations of chaos theory do, in fact, yield tightly causal results. The issue at stake in chaos theory is rather that you need to know the initial conditions of any system to an astonishingly high degree of accuracy to make accurate predictions. In practice, that's impossible to achieve. In other words, chaotic systems are not indeterminate, but underdetermined.

Craig Venter and the Nature of Life

The world has its first synthetic cell, and the question 'what is life?' is more relevant than ever.

Craig Venter may not be a god, but when he makes an announcement, the world shakes.

In 2000, the "dazzling showman of science," as he has been called, announced, together with U.S. National Institutes of Health scientist Francis Collins, a draft mapping of the human genome. So momentous was this announcement that not one but two world leaders -the U.S.'s Bill Clinton and the U.K.'s Tony Blair -felt the need to participate.

Now a decade later, Venter has done it again with the announcement that scientists at the J. Craig Venter Institute have created the world's first synthetic cell. This announcement also caught the ear of world leaders, as President Barack Obama fired off a missive to the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, giving it six months to prepare a report on the promises and perils of synthetic biology.

Environmental groups were also quick to respond to the announcement, with some calling for a moratorium on such research, and other suggesting some form of regulation is in order.

And in response to the news that Venter "created" a synthetic cell, officials with the Catholic Church warned scientists not to forget that "there is only one creator: God."

Many of the concerns expressed are not unreasonable, though they aren't without hyperbole either. To see this, let's review what Venter actually did.

Venter's team of 25 scientists mapped the genome of a bacterial cell on a computer, modified it, broke it into 1,100 pieces and synthesized the pieces using four chemicals. They then assembled the genome fragments, and transplanted the complete genome into a cell that had had its genome removed. The synthetic genome was then "booted up" and the new "synthetic" cell began self-replicating.

Naturally, Venter emphasizes the promise of such research: The U.S. National Institutes of Health have provided him with funding for work that could lead to rapid development of flu vaccines, and Exxon has promised funding to create bacteria that can produce biofuels from algae. Beyond that, it might be possible to create bacteria that can aid in cleaning up oil spills, something that looms large in the American consciousness at present.

But just as advocates emphasize the promise of synthetic biology, critics highlight safety and security concerns. There is always the fear that a laboratory-created pathogen could escape the lab, and wreak havoc on the public and the environment. This doesn't have to occur by accident: Critics note that bioterrorists could synthesize their own pathogenic bacteria and hold the world hostage, if there is any world left.

That's a little dramatic, of course, but synthetic biology's potential threat to our safety and security is worthy of consideration. Curiously, though, the public doesn't seem particularly concerned, possibly because they don't see the potential threats as appreciably different from those presented by genetic engineering, which has already be the subject of intense debate, and more than a few sci-fi novels.

What has piqued public interest, though, is the suggestion that synthetic biology amounts to playing God. This was, of course, a charge also levelled at genetic engineering, and at virtually every new technology. But there seems to be something special about synthetic biology, since all this talk about creating a synthetic cell led some people to question whether Venter created life.

Life, but Not as We Know It

Last week researchers in America announced that they had created a new kind of artificial life. Is this venture into the unknown fraught with danger, or a useful step forward with beneficial consequences for us all?

To many people, the idea of a living being suggests something that is more than just atoms but also a thing formed with a divine spark or a vital essence. But now what we mean by life itself will have to change following the creation by Craig Venter of the world’s first "synthetic cell". It is, as Venter puts it: "The first self-replicating species that we’ve had on the planet whose parent is a computer." Venter, the biologist who mapped the human genome in 2001, has designed a bacterial genome on a computer, building the genome from scratch using chemicals, inserting the genome into a hollowed-out cell and then watching that cell reproduce. But have Venter and his colleagues really synthesised new life in the laboratory? And if so, what does this achievement tell us about life itself, and what benefits – and ethical dangers – might it bring to mankind?

The cell created by Venter and colleagues at the J. Craig Venter Institute in Maryland is the result of a research programme that has lasted more than a decade and cost around US$40m. As reported in the journal Science, the cell was made in a multi-stage process that included the sequencing, or mapping out, of the one million chemical bases of the bacterium Mycoplasma mycoides. After digitising this code on a computer and tweaking it to eliminate a few unwanted genes and add in "watermarks" that would identify the genome as synthetic, the researchers split the genome into about 1,000 segments of equal length. The job of actually building these segments fell to an outside synthesis company.

Then, with the segments in hand, Venter’s group stitched them together using yeast and inserted the complete synthesised genome into the cell of a different, but related, bacterium. Finally, with the genome of the host bacterium destroyed as a result of the transfer, the cell reproduced to generate multiple copies of Mycoplasma mycoides. The breakthrough has created intense media interest worldwide and has clearly impressed many scientists and other academics, none more so than Arthur Caplan, a professor of bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States. Describing the work as "monumental", he argues it "brings to an end a 3,000-year-old debate about the nature of life" – whether living things are fundamentally different to non-living things in that they require some kind of a vital spark to animate them. For Caplan, the fact that Venter and co-workers created a living, reproducing cell using a genome that was built up from chemicals and not from other living matter means that the debate has now been settled. "Vitalism has been put to bed," he says.

Scientific Fundamentalism Goes Off the Rails

Dogmatism obscures the fact that we humans "are truly extraordinary," Marilynne Robinson tells Martin Levin.

Martin Levin: What possessed you to immerse yourself in the roiling waters of the science-religion wars?

Marilynne Robinson: I happen to be deeply interested in science and religion, so well disposed toward them both that the idea that they are natural adversaries has always bothered me. And I am fascinated by the idea that civilizations generate a hum of insight, invention, disputation, affirmation and controversy, each one like a great mind engaged with its own preoccupations. So for me, attentiveness to these "wars" is attentiveness to the unfolding of human history. That said, the issues that emerge in any culture can be profound or vacuous, brilliantly articulated or dealt with crudely. Science and religion are both profoundly important to our culture, so the integrity of the conversation around them is important as well.

G&M;: What determined your approach?

MR: I think of Absence of Mind as a critique of a prevailing curriculum, which is the actual basis for the world view that in the context of this controversy is called "scientific." These new-atheist writers carry forward an elderly tradition of polemic against religion which predates modern science and has always been and still is dependent upon positivist notions of rationalism and of the nature of physical reality. So I approach the subject as a problem in the history of ideas.

G&M;: Despite the assault of science on religion, it's only in apparent decline in the West and seems to growing in reach and, indeed, fervour in much of the rest of the world. How do you account for this?

MR: Has science in fact assaulted religion? Or is it only that the prestige of science has been appropriated in order to make an argument against religion appear authoritative? Somehow it seems to have been accepted by people on both sides of the question that religion stands or falls on the literal truth of one reading of Genesis I. It could as well be argued, for those who attach importance to such things, that the Genesis account is surprisingly consistent with the Big Bang, with the emergence of life in progressive stages, and with the remarkable phenomenon of speciation. But these questions only seem important because the actual substance of religion, the thought and art that have made it the great germinative force behind civilization, are not consulted by people on either side.

How Religious Are Scientists?

An interview with Elaine Howard Ecklund

It’s hard to think of an issue more contentious these days than the relationship between faith and science. If you have any doubt, just flip over to the science blogosphere: You’ll see the argument everywhere.

In the scholarly arena, meanwhile, the topic has been approached from a number of angles: by historians of science, for example, and philosophers. However, relatively little data from the social sciences has been available concerning what today’s scientists actually think about faith.

Today’s Point of Inquiry guest, sociologist Dr. Elaine Ecklund of Rice University, is changing that. Over the past four years, she has undertaken a massive survey of the religious beliefs of elite American scientists at 21 top universities. It’s all reported in her new book Science vs. Religion: What Scientists Really Think.

Ecklund’s findings are pretty surprising. The scientists in her survey are much less religious than the American public, of course—but they’re also much more religious, and more "spiritual," than you might expect. For those interested in debating the relationship between science and religion, it seems safe to say that her new data will be hard to ignore.

Elaine Howard Ecklund is a member of the sociology faculty at Rice University, where she is also Director of the Program on Religion and Public Life at the Institute for Urban Research. Her research centrally focuses on the ways science and religion intersect with other life spheres, and it has been prominently covered in USA Today, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Newsweek, The Washington Post, and other prominent news media outlets. Ecklund is also the author of two books published by Oxford University Press: Korean American Evangelicals: New Models for Civic Life (2008), and more recently the new book Science vs. Religion: What Scientists Really Think (2010)

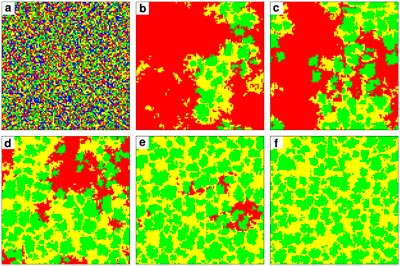

Physicists Study How Moral Behaviour Evolved

A statistical-physics-based model may shed light on the age-old question "how can morality take root in a world where everyone is out for themselves?" Computer simulations by an international team of scientists suggest that the answer lies in how people interact with their closest neighbours rather than with the population as a whole.

Led by Dirk Helbing of ETH Zurich in Switzerland, the study also suggests that under certain conditions, dishonest behaviour of some individuals can actually improve the social fabric.

Public goods such as environmental resources or social benefits are often depleted because self-interested individuals ignore the common good. Co-operative behaviour can be enforced via punishment but ultimately co-operators who punish will lose out to co-operators who don't punish because punishing requires time and effort. These non-punishing co-operators then lose out to the non co-operators, or free riders. With free riders dominant the resource is depleted, to the detriment of everyone – a scenario known as "tragedy of the commons".

How, then, does co-operation arise? Some researchers have proposed that co-operators who punish could survive through "indirect reciprocity", the idea that working for the common good will enhance a person's reputation and ensure that they benefit in the future. Helbing's group, however, has shown that this is not needed for co-operation to flourish.

Emergent phenomena

They came to this conclusion by focusing on how individuals behave with their nearest neighbours, rather than a wider group that is representative of the entire population. Like nearest-neighbour models of magnetism – which are often more realistic than mean-field approximations – they say that this approach captures "emergent" phenomena that would otherwise be lost.

Science Warriors' Ego Trips

The champions of empiricism show an unattractive hubris when they go after what they see as pseudoscience.

Standing up for science excites some intellectuals the way beautiful actresses arouse Warren Beatty, or career liberals boil the blood of Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh. It's visceral. The thinker of this ilk looks in the mirror and sees Galileo bravely muttering "Eppure si muove!" ("And yet, it moves!") while Vatican guards drag him away. Sometimes the hero in the reflection is Voltaire sticking it to the clerics, or Darwin triumphing against both Church and Church-going wife. A brave champion of beleaguered science in the modern age of pseudoscience, this Ayn Rand protagonist sarcastically derides the benighted irrationalists and glows with a self-anointed superiority. Who wouldn't want to feel that sense of power and rightness?

You hear the voice regularly—along with far more sensible stuff—in the latest of a now common genre of science patriotism, Nonsense on Stilts: How to Tell Science From Bunk (University of Chicago Press), by Massimo Pigliucci, a philosophy professor at the City University of New York. Like such not-so-distant books as Idiot America, by Charles P. Pierce (Doubleday, 2009), The Age of American Unreason, by Susan Jacoby (Pantheon, 2008), and Denialism, by Michael Specter (Penguin Press, 2009), it mixes eminent common sense and frequent good reporting with a cocksure hubris utterly inappropriate to the practice it apotheosizes.

According to Pigliucci, both Freudian psychoanalysis and Marxist theory of history "are too broad, too flexible with regard to observations, to actually tell us anything interesting." (That's right—not one "interesting" thing.) The idea of intelligent design in biology "has made no progress since its last serious articulation by natural theologian William Paley in 1802," and the empirical evidence for evolution is like that for "an open-and-shut murder case."

Pigliucci offers more hero sandwiches spiced with derision and certainty. Media coverage of science is "characterized by allegedly serious journalists who behave like comedians." Commenting on the highly publicized Dover, Pa., court case in which U.S. District Judge John E. Jones III ruled that intelligent-design theory is not science, Pigliucci labels the need for that judgment a "bizarre" consequence of the local school board's "inane" resolution. Noting the complaint of intelligent-design advocate William Buckingham that an approved science textbook didn't give creationism a fair shake, Pigliucci writes, "This is like complaining that a textbook in astronomy is too focused on the Copernican theory of the structure of the solar system and unfairly neglects the possibility that the Flying Spaghetti Monster is really pulling each planet's strings, unseen by the deluded scientists."

Theology: Natural and Unnatural

Is there any possible defence for "Intelligent Design"? Is there any way for theists to abandon the idea?

Steve Fuller is the sociologist of science notorious for arguing that Intelligent Design was not necessarily a bad research programme even though it was rotten science. In this capacity he appeared as a witness for the defence in the Dover trial in the US, the most recent attempt to smuggle creationism into the public school system there. He has written a new book on science as the heir to religion, which will be published later this spring, and there will be a Question series about this later.

Commissioning pieces for this got me thinking about the boundaries of natural theology and how we can classify it. It is an undisputed fact that many great scientists have been driven by Christian faith and the roots of modern science lay in the belief that the scientist was "reading the book of Nature", which was understood to be a revelation of God's purposes and character quite as much as the other Book, the Bible was.

This was certainly Newton's motivation, and Faraday's. But it seems also to have been contested from an early stage. Looking back at Wesley's pamphlet on the Lisbon earthquake, which was written much closer to Newton's death than Faraday's, we can see him already arguing against an atheist who believes only in "the fortuitous concourse and agency of blind material causes." So we know that there were materialists to argue against. What there were not, then, were believers in scientific progress, nor anyone who could foresee the enormous advances of the nineteenth century. For Wesley the response to plague was prayer, not bacteriology.

The progressive or whiggish account of natural theology would say that in order to find the hidden regularities of nature we needed to believe they were there, and, Christian faith gave scientists the confidence needed to do so. But – this account continues – once the architecture of the universe had been sketched out, the need for an architect receded. The elegant mathematics of the universe that physics revealed became their own justification: Laplace, when asked what God did in his model of the solar system, replied "I have no need for that hypothesis"; later, something similar happened in biology under Darwin's influence.

Natural theology had started as a way of understanding God; in the eighteenth century it became a way of proving God's existence, which is something rather different, which turned out to be catastrophic for Christian apologetics, as is shown by the fact that Richard Dawkins works entirely within this tradition: he shows instance after instance of design in the natural world, and then shows that there is no need for a designer, and that if any agency had designed the natural world we see, we couldn't call it wise or loving.

But Dawkins, here, is kicking at an open door. Many others have been through it before him. Once you destroy the idea that science can prove the existence of God, or can discover things that only God's existence can explain, the first half of natural theology also looks pointless: why investigate the nature of a non-existent being?

'Is God Dying?'

Questions on morality, evolution and the mind

Are we evolving away from belief in God? Why did thousands of intelligent people let themselves be deceived by investment fraud king Bernie Madoff? Is morality really in decline in the West and can it be reconstructed?

Such questions are in the air at a seminar on science, morality and the mind at the University of Cambridge, this weekend sponsored by the Templeton Foundation. I've participated in the Templeton-Cambridge Fellowships in Science & Religion since 2005. And for the next few days, I'd like to bring you along for a taste of the lectures and discussions.

It all starts with questions. Fraser Watts, a professor of theology and science, and Director of Studies, Queens' College set the program off with a wave of his own: What can science tell us about the origin and workings of morality? How did moral capacity arise? Is it all evolutionary? What's the role of neuroscience? What goes on in the brain when we're making moral judgments? Can we use this knowledge to reconstruct morality?

Michael Reiss, Professor of Science at the Institute of Education University of London, a specialist in evolutionary biology (and an ordained Anglican priest) walked us through the history of theories on altruism as an evolutionary phenomenon (like vampire bats who support each other by offering up blood if a mate didn't succeed in his own hunting) and the advantages of being good at deception (think Bernie Madoff).

Even so, just knowing something has an evolutionary origin "tells you nothing about whether it is valid or useful," Reiss says.

Atheist with a Soul

Philosopher and novelist Rebecca Goldstein speaks with Martin Levin about God and godlessness, and her new novel

I’m thinking that Cass, who’s called an "atheist with a soul," is the character who most embodies your own views, his disbelief in God combined with a larger respect for the religious impulse.

He is. In terms of his life, he’s a little hapless and prone to be taken over by personalities larger than his own. I hope I’m not like that, but in terms of his world views, I am with him.

Tell me about Azarya [a six-year-old mathematical genius whose abilities will be sacrificially lost in the Hasidic world in which he lives.

I thought of this story at least 15 years ago and just didn’t want to write it because I found it heartbreaking and I knew it would have to be tragic. It was an impossible dilemma I was putting this kid in, and I actually thought I’d have to kill him. I resisted writing this for a very long time, but when I got involved with the New Atheism, I thought I could use it as a platform for the Azarya story. His story is the heart of the novel.

Your last book was about Spinoza, and his spirit seems to hover over this one as well.

Spinoza is the great demonstrator that there can be deep experience of transcendence and the sublime, and what one could call a spiritual experience that is not about God. It is about being itself. Cass endorses this view and often expresses himself this way.

The grounding of morality seems to be an important theme, especially as it emerges in the climactic formal debate between Cass and a professor who’s a believer.

One of things I wanted to show was that there’s a fallacy in understanding the grounds of morality, that you don’t need God to be moral, sometimes quite the contrary. In the U.S, religious agendas, especially under the last administration, were being legislated and intruding on things like stem-cell research. You hear people say that the godless must be immoral, since you need God to ground morality. No politician in America can say they don’t believe in God. How could they be moral?

What do you see as the future for atheism, since religion seems to be declining only in Western Europe and growing throughout the rest of the world.

Europe went through its Enlightenment only following protracted, horrible religious wars, when people were convinced that their earlier certitudes were untrustworthy, and modern science and modern philosophy grew out of this. A large part of the world hasn’t gone through this yet. Europe had to have half of its population wiped out before the voices of reason got listened to. But that took a long time. Can we afford that when we have the kind of weaponry that advances in science have given us? We’re in quite a predicament. These very primitive religious emotions – to see the strength of their gathering is terrifying.

Are Science and Atheism Compatible?

Science brings no comfort to to anyone with dogmatic beliefs about world.

The General Synod this morning held a debate on whether science and religion are mutually exclusive, full of ordained scientists arguing that of course they are, and indeed the final vote was 241 to two in favour of the motion. I have failed to establish the identity of the dissident two. Faced with such a consensus I thought it might be fun to flip the question on its back and ask to what extent science is compatible with atheism.

Obviously the two are closely linked, in as much as science assumes the falsity, or at least irrelevance, of supernaturalism. But science is more than physics and chemistry, more even than biology, and the human sciences challenge a lot of beliefs held by many atheists.

The modern efflorescence of evolutionarily inspired psychology and sociology tells us that the elements of religion are natural, and unavoidable, and sometimes useful; that they are present in all societies, whether literate or pre-literate, whether in states or hunter-gatherer, though they are combined in very different forms of social organisation.

So we learn at the very least that they can't be abolished. This doesn't show that they need be combined into things we call "religions"; but at the very least they will tend to combine into social groupings and mechanisms which perform the same functions.

Further, the sociology of religion shows clearly that modern monotheistic religion is not an intellectual pursuit. People do not join churches because they agree with the doctrines. Nor do they often leave for intellectual reasons. They join – and leave – for all sorts of largely social reasons, and even within the churches, their allegiance to, and knowledge of, the official doctrine is slight. Heresy can matter enormously, but that's because it defines an outgroup. And the execration of heretics flourishes among atheist societies, too. It seems to be very widespread social mechanism.

A Very Modern Illusion

Charles Taylor shows how faith and scientific progress both require leaps into the unknown

Is science closer to religion than is typically assumed? Is religion closer to science? Might rational enquiry, based on evidence, share similarities with faith? These questions were raised by Charles Taylor, the distinguished Canadian philosopher, speaking at a Cambridge University symposium (pdf). He suspects that in the modern world we've bought into an illusion, one that posits a radical split between reason and revelation. Today, given the tension and violence that arises from misunderstandings about both, is a good time to examine them again.

The illusion, if that is what it is, emerged after the Enlightenment, when epistemological authority was questioned. It came to be assumed that you have to chose between one or the other – or, at least, if you appeal to revelation, its "truth" will only stand if allowed by the court of reason.

The new power invested in reason itself arose from the tremendous success of the natural sciences. Physics, geology and the like set a new standard of rational enquiry that is couched in procedural terms. Hence, what is rational has come to be equated with what is logically coherent. Further, it must be derived by proper methods including repeated observation and correct inference. In short, it's what scientists do.