Origins of Universe

Evangelicals Question the Existence Of Adam And Eve

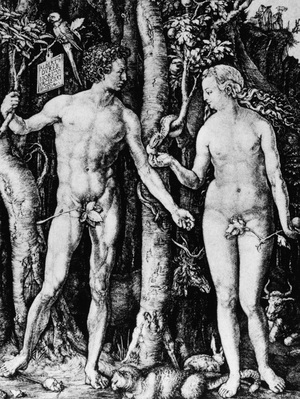

Let's go back to the beginning — all the way to Adam and Eve, and to the question: Did they exist, and did all of humanity descend from that single pair? According to the Bible (Genesis 2:7), this is how humanity began: "The Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul." God then called the man Adam, and later created Eve from Adam's rib.

Polls by Gallup and the Pew Research Center find that four out of 10 Americans believe this account. It's a central tenet for much of conservative Christianity, from evangelicals to confessional churches such as the Christian Reformed Church. But now some conservative scholars are saying publicly that they can no longer believe the Genesis account. Asked how likely it is that we all descended from Adam and Eve, Dennis Venema, a biologist at Trinity Western University, replies: "That would be against all the genomic evidence that we've assembled over the last 20 years, so not likely at all."

Researching The Human Genome

Venema says there is no way we can be traced back to a single couple. He says with the mapping of the human genome, it's clear that modern humans emerged from other primates as a large population — long before the Genesis time frame of a few thousand years ago. And given the genetic variation of people today, he says scientists can't get that population size below 10,000 people at any time in our evolutionary history.

To get down to just two ancestors, Venema says, "You would have to postulate that there's been this absolutely astronomical mutation rate that has produced all these new variants in an incredibly short period of time. Those types of mutation rates are just not possible. It would mutate us out of existence." Venema is a senior fellow at BioLogos Foundation, a Christian group that tries to reconcile faith and science. The group was founded by Francis Collins, an evangelical and the current head of the National Institutes of Health, who, because of his position, declined an interview.

And Venema is part of a growing cadre of Christian scholars who say they want their faith to come into the 21st century. Another one is John Schneider, who taught theology at Calvin College in Michigan until recently. He says it's time to face facts: There was no historical Adam and Eve, no serpent, no apple, no fall that toppled man from a state of innocence. "Evolution makes it pretty clear that in nature, and in the moral experience of human beings, there never was any such paradise to be lost," Schneider says. "So Christians, I think, have a challenge, have a job on their hands to reformulate some of their tradition about human beginnings."

Science and Censorship

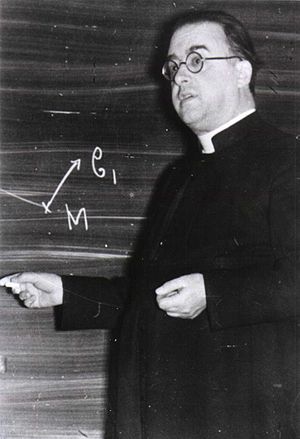

Science journal Nature picked up on my post a few weeks ago on Sidney van den Bergh’s paper on Georges Lemaître and Edwin Hubble.

Time for an update on whether the Belgian Father of the Big Bang’s seminal paper was censored in deference to Hubble when it was translated into English.

On Monday, Nature News blog featured a discussion with University of Witwatersrand astronomer David Lazar Block, who has followed up on van den Bergh’s paper with an arxiv pdf of his own.

As Block shows, there’s been some interesting new information on the case unearthed in the archives of University of Louvain (where Lemaître taught), thanks to the detective work of Dominique Lambert, a physicist and professor of the history and philosophy of science at the University of Namur in Belgium, and author of Un Atome d’Univers, the first comprehensive biography of Lemaître. (Lambert’s excellent book was a primary source for my own short bio of the Belgian priest-physicist.)

It now appears that Lemaître translated his own paper in 1931, and agreed to leave out his derivation of what’s become known as the Hubble parameter, when it was politely suggested he do so by the RAS editor, Scottish astronomer William Marshall Smart. According to Nature’s assessment:

"In a 1931 letter, Scottish astronomer William Marshall Smart, who handled the translation for the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, writes to Lemaître to ask him to translate his paper from paragraphs 1-72. That would carefully omit paragraph 73, the equation in which the determination of the constant that later became known as Hubble’s constant appears. While this doesn’t demonstrate that Hubble communicated with or influenced Smart, Block notes that Smart would have been aware of Hubble’s desire to be credited with determining the Hubble constant and his "complex personality."

Why Hubble's Law . . . Wasn't Really Hubble's

File this one under "Astronomers Behaving Badly"

An interesting paper was posted to Cornell’s Physics arXiv this past week, concerning a key point in the history of the Big Bang Theory.

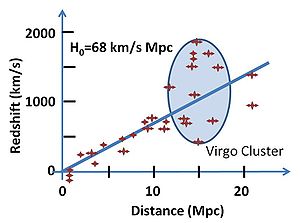

As most popular science books attest, American astronomer Edwin Hubble gets the credit for ‘discovering’ the expansion of the universe in 1929 when he published observational data showing red-shifts for several galaxies (at the time they were regarded as extra-galactic nebulae, not galaxies). The red-shifts presented a puzzle to Hubble; their relative velocity, based on Doppler shift, was proportional to their distance from the Earth. He was reluctant to conclude this relationship provided evidence to support the claim that the universe was dynamic.

But two years before, in 1927, Georges Lemaître, a Belgian Catholic priest and physicist, published a paper in an obscure Belgian journal, "Annales de la Societe Scientifique de Bruxelles." In that paper, he showed that the data collected by Hubble and two other astronomers up to that time was enough to derive a linear velocity-distance relation between the galaxies, and that this supported a model of an expanding universe based on Einstein’s equations for General Relativity.

Lemaître’s paper was really the first attempt by a scientist to ground cosmology in something more solid than abstractions and philosophy. (I covered much of this in my biography of Lemaître in 2005.)

The standard story goes that Lemaître’s work was ignored at first, because he chose to publish his paper in the Belgian journal rather than a more prominent journal like "Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in Britain."

After Hubble published his findings in 1929, he, Einstein, British astronomer Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, and Dutch astronomer Willem de Sitter, all gathered at a special meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society and pondered how they could account for such developments based on static universe models that Einstein and de Sitter had derived with General Relativity.

Seeing that no one realized the significance of his earlier work, Lemaître sent a note to Eddington, in essence, jostling his elbow and reminding his former mentor that he had a solution and had already sent a copy of the paper to him two years before.

Chagrined, Eddington immediately dug up his copy, had the paper translated and published in the Monthly Notices, and Lemaître’s work was finally recognized. Up to a point.

Lemaître was never given the credit for deriving the linear velocity-distance relation of the receding galaxies, a relation that has always been known as Hubble’s Law, even though it is explicit in his original 1927 paper.

Too Much Heat, Not Enough Light in the Creationism War

The near hysterical way in which intelligent design is treated online only suits those who seek to politicise evolution.

The most dismaying feature of the rise of creationism and intelligent design (ID) in the present day is the success advocates have in distorting so much of the wider public discussion of evolution. In short, evolution has become as much a political question as one of modern science. Culture wars, over the place of religion in society, show no sign of lessening. And so sadly it seems that creationism and ID will remain strong too, because what sustains them is not any serious contribution to science or theology, but precisely the heat of dispute.

For example, last week I was talking with a senior biochemist at Cambridge University. He reported that he could not recall a single mention of the word "creationism" during the time he worked in Turkey, which was for much of the 1970s. Nowadays though, it dominates the discussion at a public level – thanks to the activities of individuals like Harun Yahya, whose polemical and widely distributed books, such as The Atlas of Creation, advocate old Earth creationism.

At least this can be tackled head-on, for the very reason that it is out in the open. Many in the Muslim world are now doing so. I was also fortunate enough to speak with Rana Dajani last week, a Jordanian molecular biologist. She believes part of the problem is that Darwin was only recently translated into Arabic, and so many people do not have access to quality information about evolution. They only have the polemic and the politics. It's a deficit she, for one, is working hard to put right.

But the insidious effects of the culture clashes run deeper too. Consider the current case of the academic journal, Synthese.

Synthese is a well-respected philosophy publication, with past contributors including Thomas Nagel and Jerry Fodor. It recently had a guest-edited special issue on "Evolution and Its Rivals". One article in this issue included a critique of the work of Francis Beckwith, a professor at Baylor University. If I tell you that last month he gave a talk entitled, "No God, No Good: Why the Moral Law Requires a Moral Lawgiver", you can see where he's coming from.

Allegedly, friends of Beckwith complained at the personal nature of the published critique.

Creationism Lives on in US Public Schools

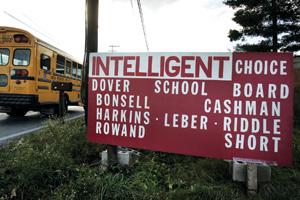

IN DOVER, Pennsylvania, five years ago, a group of parents were nearing the end of an epic legal battle: they were taking their school board to court to stop them teaching "intelligent design" to their children.

The plaintiffs eventually won their case, and on 16 October many of them came together for a private reunion. Yet intelligent design and the creationism for which it is a front are far from dead in the US, and the threat to the teaching of evolution remains.

Cyndi Sneath was one of the Dover plaintiffs who had a school-age son at the time of the trial. She has since become an active member of the American Civil Liberties Union and a member of the Dover Area School Board. "My interest in public education and civil liberties was certainly sparked by the trial," she says. "And that interest permeates our family discussions."

Chemistry teacher Robert Eschbach, who was also a plaintiff, says the trial has made teachers less afraid to step on people's toes when it comes to evolution. It "forced me to be a better educator", he says. "I went back and read more of the history around Darwin and how he came to his conclusions."

None of this means that the Discovery Institute, the Seattle-based think tank that promotes intelligent design, has been idle. The institute helped the conservative Louisiana Family Forum (LFF), headed by Christian minister Gene Mills, to pass a state education act in 2008 that allows local boards to teach intelligent design alongside evolution under the guise of "academic freedom".

Philosopher Barbara Forrest of Southeastern Louisiana University, another key witness for the Dover plaintiffs in 2005, testified against the Louisiana education act. "Louisiana is the only state to pass a state education bill based on the Discovery Institute's template," she says. Similar measures considered in 10 other states were all defeated.

Forrest heads the Louisiana Coalition for Science, and has been monitoring developments since the bill passed. In January 2009, the Louisiana Board of Elementary and Secondary Education (BESE) approved a policy that prevents Louisiana school boards from stopping schools using supplementary creationist texts hostile to evolution, such as books published by the Discovery Institute.

Creation in a Gulping Worm

The exquisite complexity of a tiny and wholly insignificant creature shows Richard Dawkins is right about creationism

Some years ago I wrote a book about a very small, transparent hermaphrodite worm, described by Lewis Wolpert as the most boring organism in existence.

The fascinating thing about this nematode, c.elegans, was that it was the best understood and most studied multi-cellular organism in the world, the first to have its genome completely sequenced; yet it still wasn't understood. You would have thought it would be quite impossible for it to do anything unpredicted or impossible to understand. It has no brain, and only 959 cells (for the hermaphrodite). Every single cell in its body is now mapped from the moment of emergence to its death. But until recently, no one knew how it did anything so simple and vital as feed itself. We knew what it ate – bacteria – and how it crushed and digested them; but the worm is a filter feeder, which manages somehow to separate the bacteria from the liquid that they swim in and no one knew exactly how. It was all in the fine timing of the contractions as it swallows, but there are no physical filters in the worm. Whales have whalebone, but worms have no wormbone.

Now a kind reader of the book has sent me a paper which he published last year which shows exactly how the filtering was done. Using very high speed video – 1000 frames a second – the team managed to isolate the way that two independent patterns of contraction separate the solid from liquids in a passage smaller than a human hair. I think it is reasonable to say that in purely formal terms there is more complexity and harmony in the stomach of an almost invisible nematode worm than in the most complex and harmonious work of art ever created.

The worm is, as I say, quite stupefyingly boring, small and, by animal standards, simple. It lives in literally uncountable billions in earth all over the world. But when you contemplate the effort, the time and the money required to unravel the complexity of even so insignificant a creature, it is easier to understand the futility of creationism.

Asteroid Ice Hints at Rocky Start to Life on Earth

Cool discovery suggests asteroids brought water and organic material.

A slushy cocktail of water-ice and organic materials has been directly detected on the surface of an asteroid for the first time. The finding strengthens the theory that asteroids delivered the ingredients for Earth's oceans and life, and could make astronomers rethink conventional models for how the Solar System evolved.

It has long been thought that asteroids, which lie in a belt between Mars and Jupiter, are rocky bodies that sit too close to the Sun to retain ice. By contrast, comets, which form further out beyond Neptune, are ice-rich bodies that develop distinctive tails of vaporized gas and dust when they approach the Sun. However, this distinction was blurred in 2006 by the discovery of small objects with comet-like tails in the asteroid belt1, says astronomer Andrew Rivkin of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

To investigate the composition of these 'main-belt comets', Rivkin and his colleague Joshua Emery, of the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, turned the infra-red telescope at Mauna Kea, Hawaii, onto the asteroid 24 Themis — the parent body from which two of the smaller comet-like asteroids observed in 2006 were chipped. Emery and Rivkin took seven measurements of 24 Themis over a period of six years, each time looking at a different face of the asteroid as it travelled around its orbit. They consistently found a band in the absorption spectrum of light reflected from its surface that indicated the presence of grains coated in water ice, as well as the signature of carbon-to-hydrogen chemical bonds — as found in organic materials. Rivkin and Emery's work is published in this week's Nature2.

"Astronomers have looked at dozens of asteroids with this technique, but this is the first time we've seen ice on the surface and organics," says Rivkin.

The result was independently confirmed by a team led by Humberto Campins at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. He and his colleagues observed 24 Themis for 7 hours one night, as it almost fully rotated on its axis. "Between us, we have seen the asteroid from almost every angle and we see global coverage," says Campins. He and his team also publish their findings in this week's Nature3.

Julie Castillo-Rogez, an astrophysicist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, describes the findings as "huge". "This answers the long-term question of whether there is free water in the asteroid belt," she says.

British Creationists: Some Numbers

Those who reject Darwinism in Britain are numerous, largely irreligious, and ignorant of science.

The previous blog discussed how creationist opinion formers think: given that formal creationism is a belief that must be taught, this seems a sensible line of enquiry. By formal creationism, I mean the belief that most scientists have more or less malevolently misinterpreted the data for the last 200 years to prove that the Bible is not literally true. That survey dealt only with 50 opinion formers, interviewed in depth. But how many people do they represent?

The answer to that comes from an earlier Theos survey, published this spring, which contained truly shocking figures as to the amount of biological ignorance in the country; but at the same time, it suggested that this had nothing much to do with religion. How could it, when the number of people reporting either Young Earth creationism, or ID, at 25% is something like five times as large as the combined Muslim and evangelical population of this country? Twice as many people are confused about what they believe, and only another quarter are convinced of the truth of evolution.

These results were obtained by a fairly sophisticated set of questions, designed to discover what people actually believed, rather than the labels they would attach to it. Much of it, I think, is the result of innumeracy in general: someone for whom all numbers above about a thousand are indistinguishable blur may very well think that the earth is 10,000 years old and mean by this that it is really really seriously, like, old.

Such people don't pose any threat to the teaching of science in schools. They just make it look entirely pointless, since they have themselves been "educated". But that is a different and more serious problem than religious creationism. The anti-Darwinians interviewed in the most recent survey are a tiny, articulate and self-conscious minority. The real problem for public understanding, as anyone knows who has done any science writing, are the millions of people whose position is that they don't know, don't care, and don't want to do either.

Why Detecting Nothing is Really Something in Gravitational-Wave Project

Vuk Mandic and his colleagues made big headlines in scientific journals last week by finding nothing — nada, zilch, zippo — in their search for gravitational waves.

In order to comprehend why nothing can be something big in astrophysics, we need to look first at the stakes in this quest for gravitational waves.

These mysterious waves were predicted in Albert Einstein's 1916 general theory of relativity. If mass accelerates in some way -- say, you pick up a child or drive a car -- you have these ripples in space and time, the theory goes. But we Earthlings are mere specks on a universal scale, so any waves we make are insignificant.

Instead, scientists are looking for the waves in connection with mega-scale cosmic events: collisions of black holes, shock waves from supernova explosions — and the granddaddy of all, the Big Bang.

Influence has been observed

The gravitational waves' influence on stars has been observed. But the waves themselves never have been directly detected. If they were, it would set off a revolution in physics, opening an entirely new way of looking at the universe.

"Black holes, we can't see at all at this point ... super nova explosions are not understood yet," Mandic said. "So we hope that gravitational waves would allow us to open another window into astronomy."

Scientists also believe that the Big Bang created a flood of gravitational waves that still fill the universe and carry information about the immediate aftermath of that colossal explosion. No one has ever been able to study the full fiery nature of the physics at play in the moments following the Bang. In that sense, gravitational waves would have a unique tale to tell, Mandic said.

Stephen Hawking Is Making His Comeback

Stephen Hawking, the master of time, space, and black holes, steps back into the spotlight to secure his scientific legacy—and to explain the greatest mystery in physics: the origin of the universe.

influence on cosmology and physics is clearly not what it once was. In the popular realm, too, his star has dimmed. As the Pasadena event testifies, Hawking can still pack a room, but he has lost much of his iconic status. None of his books since Brief History have come close to its runaway success. The master of black holes is himself becoming steadily less visible.

Late last year reports circulated that Hawking would be retiring from Cambridge in 2009 and that he might even leave England to join the Perimeter Institute, an innovative research center just outside Toronto. Hawking, Croasdell assured me, will neither be retiring nor abandoning Cambridge, but this year will bring a significant transition. On September 30 he will relinquish his prestigious post as the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge, a position once occupied by Isaac Newton, which Hawking has held since 1979. He turned 67 on January 8, the maximum age for holding the Lucasian chair, and so will continue at the university with a new title, Emeritus Lucasian Professor.

No one should have believed the rumors. Retiring is no more of an option for Hawking than ceasing to think would be. What he is reaching for now is closer to the opposite: a defense and extension of the kind of sweeping cosmological ideas that first shot him to fame. In other words, a capstone to his career—or, to be blunt, a comeback.

It is challenging for any academic in his sixties to reclaim the aura of youthful genius, and especially so for a man whom the popular media routinely likened to Albert Einstein. And then there is Hawking’s most formidable antagonist: his own withered body. "I imagine it has become very difficult for him to work, and that’s been the major cause of his being out of the game, so to speak," says Leonard Susskind, a theoretical physicist at Stanford University. "In the last number of years, he has been so incapacitated that it has been very difficult for him to keep up with what is happening in the field."

Nevertheless, Hawking continues his almost ludicrously grand program. "My goal is simple," he famously explained. "It is a complete understanding of the universe, why it is as it is, and why it exists at all."

With Rare Sun Blessing, Jews Marvel At Creation

Passover, or the annual celebration of Jews' exodus from Egypt, began Wednesday. This year, it's a once-in-a-generation event.

It coincides with the Birkat Hachamah — the "Blessing of the Sun" — a celebration that occurs every 28 years, when the sun is in a precise location in the sky.

To mark the occasion, a group of religious Jews gathered for a 7 a.m. standing-room-only service at the Chabad Lubavitch house in Gaithersburg, Md. Men wearing prayer shawls chanted from the Talmud before moving outside into the soft early light. It was time for a special blessing.

"Raise your hand if you did this either in 1953 or 1981. Anybody?" asked Rabbi Sholom Raichik.

Raichik surveyed the crowd of 100 men and women, and only a half-dozen hands went up. It's not surprising, since the blessing of the sun is so infrequent. He directed them to face east, punctuating the Psalms with explanations.

According to Talmudic tradition, on Wednesday morning the sun was at the exact position in the skies as it was the moment the Earth was created — 5,769 years ago. It's a complicated calculation. And after some description, the rabbi defaulted to modern technology.

listen now or download Morning Edition [3 min 10 sec]

- listen… []

Far Out

With plumes of gas and stardust reaching up like the fingers of Adam and a purple sun winking back, the "Pillars of Creation" has the high ecclesiastical wattage of a Michelangelo. But this late-20th-century masterpiece wasn’t painted by human hands. It is a digital image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope of the Eagle nebula, a celestial swarm 7,000 light-years from Earth. While the image is embraced sometimes by Christians to evoke the Garden of Eden or the Pearly Gates, what we are seeing is something real and more inspiring: a cosmic incubator hatching new stars.

Reproduced on calendars and book jackets and in coffee-table books, "Pillars of Creation" belongs among the iconic images of modern times — right up there with the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima and Ansel Adams’s "Moon and Half Dome, Yosemite National Park." More than an artifact of technology, "Pillars of Creation" is a work of art. As John D. Barrow, a professor of mathematical sciences at Cambridge University, writes in COSMIC IMAGERY: Key Images in the History of Science (Norton, $39.95), pulling such an arresting canvas from the digital signals beamed by Hubble required aesthetic choices much like those that went into the great landscape paintings of the American West.

There is no reason, for example, why the plumes had to be shown standing up. There are no directions in space. More important, the scientists processing the bit stream chose the color palette partly for dazzling effect.

"If you were floating in space you would not ‘see’ what the Hubble photographs show in the sense that you would see what my passport photo shows if you met me," Barrow writes. Following a suggestion by an art historian, Elizabeth Kessler, he juxtaposes "Pillars of Creation" with Thomas Moran’s "Cliffs of the Upper Colorado River, Wyoming Territory." Both works "draw the eyes of the viewer to the luminous and majestic peaks," Barrow writes. "The great pillars of gas are like a Monument Valley of the astronomical landscape."

Through dozens of short essays, each prompted by one of science’s visual creations, Barrow conducts his own personal tour of the universe. A picture of the Whirlpool Galaxy, with its double spirals, sets him to wondering whether it was the spark for van Gogh’s "Starry Night." The Crab nebula, the remnant of an exploding star viewed by Chinese astronomers in 1054, leads into a short discussion of pulsars, distant lights that blink so rhythmically that astronomers once wondered whether they were semaphores from L.G.M.’s — "little green men."

A Map of the Heavens

Much of the genius of Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) lay in a mix of audacity and exactitude. His boldest leaps of insight sprang from laborious plodding. Years of careful computation, based on sporadic stargazing with the crudest of instruments, lay behind his astonishing discoveries: Our earth was not the fixed center of the universe, nor did the sun and the stars move around us in perfect epicycles, as Ptolemy had argued more than a millennium earlier; in fact, our earth not only revolved around the sun but rotated on its axis. Nor were the heavens themselves static: They moved as well.

When his "On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres" finally appeared in 1543, after decades of delay — he saw the first printed copy on the very day of his death — he not only turned human beings out of the cozy nest of their fondest assumptions, but rejoiced in the eviction. In the first book of his great work, he states, "Indeed, the Sun as if seated on a royal throne governs his household of stars as they circle around him." A heliocentric cosmos demonstrated to him "the marvelous symmetry of the universe."

As Jack Repcheck demonstrates in his excellent "Copernicus' Secret: How the Scientific Revolution Began" (Simon & Schuster, 255 pages, $25), the Polish astronomer and mathematician is not simply the pure empiricist we might recall. Born as Mikolaj Kopernik in the town of Torun on the Baltic coast, Copernicus combined religious fervor with scientific rigor in almost equal measure.

Of course, this wasn't unusual in the 16th century: Virtually all scientists then were believers, but most of them looked to nature only

Time May Not Exist

Einstein, for one, found solace in his revolutionary sense of time.

No one keeps track of time better than Ferenc Krausz. In his lab at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in Garching, Germany, he has clocked the shortest time intervals ever observed.

Krausz uses ultraviolet laser pulses to track the absurdly brief quantum leaps of electrons within atoms. The events he probes last for about 100 attoseconds, or 100 quintillionths of a second. For a little perspective, 100 attoseconds is to one second as a second is to 300 million years. But even Krausz works far from the frontier of time. There is a temporal realm called the Planck scale, where even attoseconds drag by like eons. It marks the edge of known physics, a region where distances and intervals are so short that the very concepts of time and space start to break down.

Planck time—the smallest unit of time that has any physical meaning—is 10-43 second, less than a trillionth of a trillionth of an attosecond. Beyond that? Tempus incognito. At least for now.

Efforts to understand time below the Planck scale have led to an exceedingly strange juncture in physics. The problem, in brief, is that time may not exist at the most fundamental level of physical reality. If so, then what is time? And why is it so obviously and tyrannically omnipresent in our own experience? "The meaning of time has become terribly problematic in contemporary physics," says Simon Saunders, a philosopher of physics at the University of Oxford. "The situation is so uncomfortable that by far the best thing to do is declare oneself an agnostic."

The trouble with time started a century ago, when Einstein’s special and general theories of relativity demolished the idea of time as a universal constant. One consequence is that the past, present, and future are not absolutes. Einstein’s theories also opened a rift in physics because the rules of general relativity (which describe gravity and the large-scale structure of the cosmos) seem incompatible with those of quantum physics (which govern the realm of the tiny). Some four decades ago, the renowned physicist John Wheeler, then at Princeton, and the late Bryce DeWitt, then at the University of North Carolina, developed an extraordinary equation that provides a possible framework for unifying relativity and quantum mechanics. But the Wheeler- DeWitt equation has always been controversial, in

part because it adds yet another, even more baffling twist to our understanding of time.

"One finds that time just disappears from the Wheeler-DeWitt equation," says Carlo Rovelli, a physicist at the University of the Mediterranean in Marseille, France. "It is an issue that many theorists have puzzled about. It may be that the best way to think about quantum reality is to give up the notion of time—that the fundamental description of the universe must be timeless."

Pope: Science is too Narrow to Explain Creation

PARIS (Reuters) - Pope Benedict, elaborating his views on evolution for the first time as Pontiff, says science has narrowed the way life's origins are understood and Christians should take a broader approach to the question.

The Pope also says the Darwinist theory of evolution is not completely provable because mutations over hundreds of thousands of years cannot be reproduced in a laboratory.

But Benedict, whose remarks were published on Wednesday in Germany in the book "Schoepfung und Evolution" (Creation and Evolution), praised scientific progress and did not endorse creationist or "intelligent design" views about life's origins.

Those arguments, proposed mostly by conservative Protestants and derided by scientists, have stoked recurring battles over the teaching of evolution in the United States. Some European Christians and Turkish Muslims have recently echoed these views.

"Science has opened up large dimensions of reason ... and thus brought us new insights," Benedict, a former theology professor, said at the closed-door seminar with his former doctoral students last September that the book documents.

"But in the joy at the extent of its discoveries, it tends to take away from us dimensions of reason that we still need. Its results lead to questions that go beyond its methodical canon and cannot be answered within it," he said.

"The issue is reclaiming a dimension of reason we have lost," he said, adding that the evolution debate was actually about "the great fundamental questions of philosophy - where man and the world came from and where they are going."

The Anthropic Universe

It‘s called the anthropic universe: a world set up so that human beings could eventually emerge. So many physical constants, so many aspects of our solar system, so much seems to be finely tuned for our benefit. But was it? We hear from Professors Martin Rees, Paul Davies, and Frank Tipler, as well as many others, about one of the ultimate questions.

listen now or download [mp3 audio, 49 minutes, ~22.5 MB]