Neuroscience & Spirit

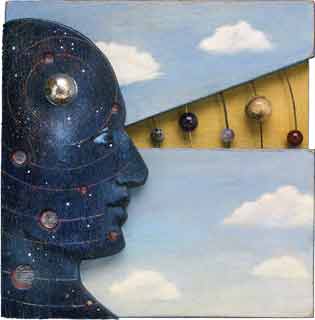

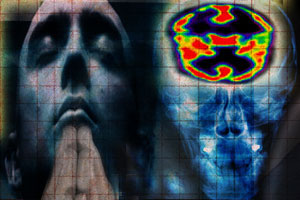

The Nature of Consciousness

How the Internet Could Learn to Feel

If you had to list the hardest problems in science -- the questions even some scientists say are insoluble -- you would probably end up with two:

Where do the laws of physics come from?

How does the physical stuff in our brains produce conscious experience?

Even though philosophers have obsessed over the "mind-body problem" for centuries, the mystery of consciousness wasn't considered a proper scientific question until two or three decades ago. Then, a couple of things happened. Brain-imaging technologies finally gave neuroscience some high-powered tools to peer inside our brains while we think. And a few renowned scientists -- most famously, Francis Crick -- claimed that neuroscientists had to tackle consciousness if they were ever going to understand the brain.

By the 1980s, Crick had jumped from molecular biology to neuroscience and moved from England to California. There he found a brilliant young collaborator, Christof Koch, the son of German diplomats who'd recently landed a job as an assistant professor of biology and engineering at the California Institute of Technology. For the next 16 years -- until Crick's death in 1994 -- they worked together, searching for the neural correlates of consciousness.

Praying Relapses Away

New findings in neuroscience help clarify why spirituality improves success with sobriety.

Old-timers in Alcoholics Anonymous love to quote Carl Jung’s Latin pun "spiritus contra spiritum"—the Spirit against the spirits—for if, as the father of analytic psychology suggested, alcoholics drink spirits to fill a hole in their soul, then getting drunk on religion may fulfill the need to drink. Yet until recently the only evidence of this magic was in the doing; you had to stand in the drunkard’s shoes to grasp the appeal of spirituality firsthand.

Now neuroscientists are beginning to explain not only why minds crippled by craving require psychological crutches to stay sober but also why spiritual pursuits serve this purpose so well—God or no God: It’s not just that addicts’ addled brains are extra vulnerable to religious ideas and group-think (for example, the newbie’s familiar "addicted to AA" syndrome); they’re chemically drawn to them as well.

Research affirms that there is in fact a kind of hole in the addict’s soul; years of drinking or drugging mute the brain’s natural pleasure pathways. Active addicts and those fresh off their substance typically have inadequate levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine—and hence to suffer from poor concentration, lack of motivation and a pesky inability to enjoy things. And newly sober, they are fragile. "While recovering alcoholics may bob along on a daily basis, they haven’t really got any flexibility in their system to respond to major events," says addiction expert Anne Lingford-Hughes, a professor at London’s Imperial College.

Brain scans of recovering addicts show that thankfully, much of the damage repairs itself in a matter of months (or years), including the ability to feel good—or good enough—sans self-medication. Quitters often report a gradually intensifying thawing of the emotions, an openness to beauty and joy…with wistful tales of forest canopies and newfound love that can be utterly nauseating to those still using!

Can Meditation Change Your Brain?

Contemplative Neuroscientists Believe It Can.

Can people strengthen the brain circuits associated with happiness and positive behavior, just as we’re able to strengthen muscles with exercise?

Richard Davidson, who for decades has practiced Buddhist-style meditation – a form of mental exercise, he says – insists that we can.

And Davidson, who has been meditating since visiting India as a Harvard grad student in the 1970s, has credibility on the subject beyond his own experience.

A trained psychologist based at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, he has become the leader of a relatively new field called contemplative neuroscience - the brain science of meditation.

Over the last decade, Davidson and his colleagues have produced scientific evidence for the theory that meditation - the ancient eastern practice of sitting, usually accompanied by focusing on certain objects - permanently changes the brain for the better.

"We all know that if you engage in certain kinds of exercise on a regular basis you can strengthen certain muscle groups in predictable ways," Davidson says in his office at the University of Wisconsin, where his research team has hosted scores of Buddhist monks and other meditators for brain scans.

"Strengthening neural systems is not fundamentally different," he says. "It’s basically replacing certain habits of mind with other habits."

Contemplative neuroscientists say that making a habit of meditation can strengthen brain circuits responsible for maintaining concentration and generating empathy.

One recent study by Davidson’s team found that novice meditators stimulated their limbic systems - the brain’s emotional network - during the practice of compassion meditation, an ancient Tibetan Buddhist practice.

That’s no great surprise, given that compassion meditation aims to produce a specific emotional state of intense empathy, sometimes call "lovingkindness."

But the study also found that expert meditators - monks with more than 10,000 hours of practice - showed significantly greater activation of their limbic systems. The monks appeared to have permanently changed their brains to be more empathetic.

William James, Part 2: The Scientific Study of Religion

James demonstrates how identifying the physiological bases for religious experience explains very little.

The Scotsman of May 1901 records how William James began the lectures that became The Varieties of Religious Experience, "in the English class-room of [Edinburgh] University, where a crowded audience assembled". He was the kind of communicator who attracted more and more auditors as a course proceeded. When, in 1908, he gave the Hibbert lectures in Oxford, the venue had to be changed from a modest library to the vast rooms of the Examination Schools building.

"It is with no small amount of trepidation that I take my place behind this desk," he opened, "and face this learned audience." The reasons for his strikingly humble tone were several. American universities had only recently started to award higher degrees, so thinkers of James' generation travelled to Europe to research. James himself had no such academic qualification.

That said, it quickly became clear that he had all the boldness of the brilliant amateur. His lectures would examine the perennial human phenomenon of religious experience, from a psychological not ecclesiastical or theological perspective. He would confine his evidence to records produced by articulate, often remarkable individuals. He would be clear to draw a difference between the nature of religious experiences, and the value of religious truths to humankind. It is easy, he notes, to slip from explaining the former to passing judgment on the latter, though the move is fallacious.

James explains why in the first lecture. He was a keen Darwinian, and so he asks us to consider the kind of evolutionary explanation for religion that argues it has some survival advantage, or that draws a connection between, say, religious emotions and sexual life. It's a reasonable hypothesis. Everything has causes. What's a mistake, though, is to think these aetiologies explain away the authority the experiences carry.

James calls that error "medical materialism". This "too simple-minded system … finishes up Saint Paul by calling his vision on the road to Damascus a discharging lesion of the occipital cortex, he being an epileptic. It snuffs out Saint Teresa as an hysteric." Paul may well have had an epileptic episode. But that's only to say that there is a biological component to all human experience. "Scientific theories are organically conditioned just as much as religious emotions are; and if we only knew the facts intimately enough, we should doubtless see "the liver" determining the dicta of the sturdy atheist as decisively as it does those of the Methodist under conviction anxious about his soul."

William James, Part I: A Religious Man for our Times

Existentially troubled and intellectually brilliant, James is still well worth reading for matters of truth, pluralism and God.

One of the many spiritual confessions that William James records in The Varieties of Religious Experience stands out. It comes in the lectures on the "sick soul". James explains that he includes it because it has the "merit of extreme simplicity". Is that code for, evidence that well fits my case?

It turns out that this particular account of existential collapse, though anonymous, was actually written by James himself. It describes one of the depressive episodes to which he was prone. (He confessed the fact a couple of years after the publication of Varieties, the book version of his Gifford Lectures of 1901.) The incident provides us with a window into the soul of the American philosopher and psychologist.

In the lecture, James says the troubled testimony came from a "French correspondent". That too is thin cover. Along with his brother, Henry James, the famous novelist, William was educated as a young man right across Europe. If you want to learn about art, why not go to Florence? Philosophy, then Germany. In 1858, aged 16, he penned a letter from London to an American friend: "We have now been three years abroad. I suppose you would like to know whether our time has been well spent. I think that as a general thing, Americans had better keep their children at home. I myself have gained in some things but have lost in others."

Languages were one gain: he was fluent in French and German and had conversational Italian. These linguistic abilities played no small part in his international renown and his colourful, literary style. As to the loses: one biographer called it "growing up zigzag", and James did have trouble deciding just what he wanted to do with his life. He thought of being an artist at first, then trained to be a doctor.

The psychology came to him when he was asked to write an introduction to the new subject, a book that finally appeared in 1890 as the hefty Principles of Psychology.

The study of religion, and the philosophy, become distinct interests after that. So, the works for which he is remembered now – the Varieties, A Pluralistic Universe, and essays such as The Will to Believe – were published relatively late in his life. He was probably never really sure of his vocation.

Why You Don't Want the Dragon-Tattooed Lady's Photographic Memory

In one of Stieg Larsson’s popular novels, Lisbeth Salander deploys her photographic memory to master a heavy mathematical tome.

The dragon-tattooed Swedish Superwoman breezes through Pythagoras’ equation (x2 + y2 = z2) and centuries of other mathematical challenges to confront the perplexing last theorem of Pierre de Fermat. Whew!

For most of us non-fictional characters, memory doesn’t work that way. And you wouldn’t want photographic memory if you read Anthony Greene’s fascinating report in the July/August issue of Scientific American Mind. Greene is a psychology professor at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. "Many people wish their memory worked like a video recording," Greene says. "How handy would that be? Finding your car keys would simply be a matter of zipping back to the last time you had them and hitting ‘play.’ You would never miss an appointment or forget to pay a bill. You would remember everyone’s birthday. You would ace every exam." So you might think. In fact, living with true photographic recall — known clinically as Eidetic memory — could be like confronting all of the information in cyberspace without the benefit of Google or any other aid for searching, sorting and organizing. "It would not let you prioritize or create the links between events that give them meaning," Greene says.All about connections

During the 20th Century, scientists established that a memory is not at all like a tidy file in an organized cabinet. Instead, memories are dispersed across regions of the brain that are responsible for language, vision, hearing, emotion and other functions. "Our brain has evolved not just for learning and memory but for the management of relations: past, present and future," Greene said. "The ability to form and retain connections gives us not just a record of events but also the foundations of comprehension." Those management networks are physically supported by neurons as they connect to and communicate with other neurons.The iBrain

The mobile communication device in your head

Here's a real-life horror story: Five people have been found buried alive inside their bodies. Paralyzed by brain injuries, they lay inert for years, seemingly oblivious to the doctors and loved ones around them. Four were diagnosed as vegetative. Then a European research team scanned their brains. It turns out they're aware; they just can't speak or move. God knows how many more are trapped like this.

On the heels of this frightening idea comes another: The scans that exposed these patients' thoughts could expose yours. They could read your mind. "Governments are interested in the thoughts of their citizens—whether their voting intentions or their propensities to crime," warns Colin Blakemore, an Oxford neuroscientist. In the European scans, he sees "the possibility that brain science could bring an era of surveillance that will make the epidemic of CCTV cameras look trivial."

Relax. The brain scans are wonderful news. The patients were trapped anyway; the scans have simply restored their ability to communicate. Better yet, that communication remains voluntary. Without the patients' cooperation, the scans would have found nothing. That's the most marvelous thing the scans have discovered: Human minds stripped of every other power can still control one last organ—the brain.

In the age of neuroscience, this sounds ridiculous. We think of the brain as its own master, controlling or fabricating the mind. The New York Times, for instance, says that when the first pseudo-vegetative patient was scanned, "areas of her motor cortex leapt to life," and "spatial areas in the brain became active"—as though these areas animated themselves. The Times of London calls the organ in the scans "the talking brain." Blakemore sees the scans as part of a new understanding: Our intentions, far from guiding of our behavior, are really just products of brain cells that have already "made up their minds."

Beyond Comprehension

We know that genocide and famine are greater tragedies than a lost dog. At least, we think we do.

On March 13, 2002, a fire broke out in the engine room of an oil tanker about 800 miles south of Hawaii. The fire moved so fast that the Taiwanese crew did not have time to radio for help. Eleven survivors and the captain's dog, a terrier named Hokget, retreated to the tanker's forecastle with supplies of food and water.

The Insiko 1907 was supposed to be an Indonesian ship, but its owner, who lived in China, had not registered it. In terms of international law, the Insiko was stateless, a 260-foot microscopic speck on the largest ocean on Earth. Now it was adrift. Drawn by wind and currents, the Insiko got within 220 miles of Hawaii. It was spotted by a cruise ship, which diverted course and rescued the crew. But as the cruise ship pulled away, a few passengers heard the sound of barking.

The captain's dog had been left behind on the tanker.

A passenger who heard the barking dog called the Hawaiian Humane Society in Honolulu. The animal welfare group routinely rescued abandoned animals -- 675 the previous year -- but recovering one on a tanker in the Pacific Ocean was something new. The U.S. Coast Guard said it could not use taxpayer dollars to save the dog. The Insiko's owner wasn't planning to recover the ship. The Humane Society alerted fishing boats about the lost tanker. Media reports began appearing about Hokget.

Something about a lost dog on an abandoned ship in the Pacific gripped people's imaginations. Money poured into the Humane Society to fund a rescue. One check was for $5,000.

Donations eventually arrived from 39 states, the District of Columbia and four foreign countries.

"It was just about a dog," Pamela Burns, president of the Hawaiian Humane Society, told me. "This was an opportunity for people to feel good about rescuing a dog. People poured out their support. A handful of people were incensed. These people said, 'You should be giving money to the homeless.'" But Burns thought the great thing about America was that people were free to give money to whatever cause they cared about, and people cared about Hokget.

Brain Science Starting to Impact Varied Fields

It used to be that only doctors were interested in brain scans, searching the images for tumors, concussions or other health problems hiding inside a patient's skull.

PHILADELPHIA (Reuters Life!) - More and more, though, images showing neurons firing in different areas of the brain are gaining attention from experts in fields as varied as law, marketing, education, criminology, philosophy and ethics.

They want to know how teachers can teach better, business sell more products or prisons boost their success rates in rehabilitating criminals. And they think that the patterns and links which cognitive neuroscience is finding can help them.

"Suddenly, neuroscience is seen as a source of answers to these questions," said Martha Farah, director of the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

"Neuroscience has gotten to the point now, in 2009, that it can actually explain many different types of human behavior that 10 years ago, certainly 20 years ago, it was nowhere near explaining," she told Reuters at a recent seminar explaining the latest progress in brain research for non-scientists.

Much of this research focuses on brain scans, especially by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which produces images showing the areas of the brain where neurons fire as the patient reacts to stimuli or thinks about something.

Activity at certain points, such as the amygdala where fear and anxiety are processed, sometimes shows connections in a person's behavior that are not visible from the outside. Brain scans also show some of the neural bases for emotions and such complex reactions as love, empathy and trust.

STRONG INTEREST AMONG LAWYERS

Neuroscience has attracted strong interest in the legal profession, where it can challenge fundamental notions of guilt, responsibility, intentions and testimony.

Law professor Deborah Denno said the United States legal system assumed the brain had a kind of on-off switch while neuroscience shows it has varying levels of consciousness.

"Now it's all or nothing -- you're either conscious and guilty or not conscious and innocent," said Denno, who teaches at Fordham University in New York.

Woman Reads Dan Brown Novel, Discovers Herself

Dan Brown's latest blockbuster, The Lost Symbol, is jampacked with surprising twists and turns — especially for Marilyn Schlitz.

"Waking up one morning to find yourself a fictional character in a best-selling novel has taken a little adjusting to," she says, laughing.

The day before The Lost Symbol arrived in bookstores, Schlitz began to notice some unusual traffic on Twitter. Rumor had it that the heroine in the book was a woman at the Institute of Noetic Sciences — a real institute in California that conducts research on things like consciousness and healing. Schlitz is president of the institute. She bought the book the next day and read into the wee hours.

"As I'm reading along and hearing the descriptions of the types of research that she's doing and the types of data that she's using to support her case, my husband would be falling asleep, and I'd be jabbing him and saying, 'Listen to this!' It was really very surprising and delightful at the same time," she says.

Surprising, because Dan Brown never contacted the institute, yet he seemed to know all about their research, even the fact that they had built a 2,000-pound electromagnetically shielded laboratory that Brown calls "the Cube." Then on the day of publication — contact.

"Dan Brown sent a very sweet e-mail saying, 'As you know, I'm a big fan of the Institute of Noetic Sciences. I had hoped to give you a heads-up,' " Schlitz says. "But because of the security around the book, he wasn't able to. But he was hoping we were enjoying the attention." They are indeed. Traffic to their Web site has increased twelvefold. New members are joining up, and journalists from places like Dateline NBC — not to mention NPR — are calling for interviews.

listen now or download All Things Considered

- listen… []

Seeking

How the brain hard-wires us to love Google, Twitter, and texting. And why that's dangerous.

Seeking. You can't stop doing it. Sometimes it feels as if the basic drives for food, sex, and sleep have been overridden by a new need for endless nuggets of electronic information. We are so insatiably curious that we gather data even if it gets us in trouble. Google searches are becoming a cause of mistrials as jurors, after hearing testimony, ignore judges' instructions and go look up facts for themselves. We search for information we don't even care about. Nina Shen Rastogi confessed in Double X, "My boyfriend has threatened to break up with me if I keep whipping out my iPhone to look up random facts about celebrities when we're out to dinner." We reach the point that we wonder about our sanity. Virginia Heffernan in the New York Times said she became so obsessed with Twitter posts about the Henry Louis Gates Jr. arrest that she spent days "refreshing my search like a drugged monkey."

We actually resemble nothing so much as those legendary lab rats that endlessly pressed a lever to give themselves a little electrical jolt to the brain. While we tap, tap away at our search engines, it appears we are stimulating the same system in our brains that scientists accidentally discovered more than 50 years ago when probing rat skulls.

In 1954, psychologist James Olds and his team were working in a laboratory at McGill University, studying how rats learned. They would stick an electrode in a rat's brain and, whenever the rat went to a particular corner of its cage, would give it a small shock and note the reaction. One day they unknowingly inserted the probe in the wrong place, and when Olds tested the rat, it kept returning over and over to the corner where it received the shock. He eventually discovered that if the probe was put in the brain's lateral hypothalamus and the rats were allowed to press a lever and stimulate their own electrodes, they would press until they collapsed.

Olds, and everyone else, assumed he'd found the brain's pleasure center (some scientists still think so). Later experiments done on humans confirmed that people will neglect almost everything—their personal hygiene, their family commitments—in order to keep

Is a Moral Instinct the Source of our Noble Thoughts?

Until not too long ago, most people believed human morality was based on scripture, culture or reason. Some stressed only one of those sources, others mixed all three. None would have thought to include biology. With the progress of neuroscientific research in recent years, though, a growing number of psychologists, biologists and philosophers have begun to see the brain as the base of our moral views. Noble ideas such as compassion, altruism, empathy and trust, they say, are really evolutionary adaptations that are now fixed in our brains. Our moral rules are actually instinctive responses that we express in rational terms when we have to justify them.

Thanks to a flurry of popular articles, scientists have joined the ranks of those seen to be qualified to speak about morality, according to anthropologist Mark Robinson, a Princeton Ph.D student who discussed this trend at the University of Pennsylvania’s Neuroscience Boot Camp.

"In our current scientific society, where do people go to for the truth about human reality?" he asked. "It used to be you might read a philosophy paper or consult a theologian. But now there seems to be a common public sense that the authority over what morality is can be found by neuroscientists or scientists."

This change has come over the past decade as brain scan images began to reveal which areas of the brain react when a person grapples with a moral problem. They showed activity not only in the prefrontal cortex, where much of our rational thought is processed, but also in areas known to handle emotion and conflicts between brain areas. Such insights cast doubt on long-standing assumptions about reason or religion driving our moral views. "A few theorists have even begun to claim that that the emotions are in fact in charge of the temple of morality and that moral reasoning is really just a servant masquerading as the high priest," University of Virginia psychologist Jonathan Haidt, one of the leading theorists in this field, has written.

Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory argues that morality is based on five concepts that evolved in all cultures: harm/care, fairness/reciprocity, ingroup/loyalty, authorty/respect and purity/sanctity. Those concepts have real-life consequences, he says — political liberals and conservatives disagree so much on so-called "culture war issues" because liberals base their moral views on the first two concepts while conservatives use all five. Other theorists such as Marc Hauser of Harvard and John Mikhail of Georgetown suggest humans have a universal moral grammar akin to the universal grammar that linguist Noam Chomsky claims underlies all the world’s languages.

The God Choice

Armed with new technology, scientists are peering into the brain to better understand human spirituality. What if, they say, God isn’t some figment of our imagination? Instead, perhaps brain chemistry simply reflects an encounter with the divine.

A few years ago, I witnessed two great British scientists in a showdown. Nine other journalists and I were on a Templeton fellowship at Cambridge University, and on this particular morning, the guest speaker was John Barrow. Almost as an aside to his talk, the Cambridge mathematician asserted that the astonishing precision of the universe was evidence for "divine action." At that, Richard Dawkins, the Oxford biologist and famous atheist, nearly leapt from his seat.

"But why would you want to look for evidence of divine action?" demanded Dawkins.

"For the same reason someone might not want to," Barrow responded with a little smile.

For the past century, science has largely discarded "God" as a delusion and proclaimed that all our "spiritual" moments, events, thoughts, even free will, can be explained through material means.

But a revolution is occurring in science. It is called neurotheology, and it is sparked by researchers from universities such as Pennsylvania, Virginia and UCLA. Armed with technology Freud never dreamed of, these scientists are peering into the brain to understand spiritual experience. Perhaps, they say, God is not a figment of our brain chemistry; perhaps the brain chemistry reflects an encounter with the divine. In that instant, I thought, there it is. God is a choice. You can look at the evidence and see life unfolding as a wholly material process,

Decoding the Mystery of Near-Death Experiences

Most scientists say that when the brain stops operating, so does consciousness. Materialists say the visions people report experiencing close to death are hallucinations. A few scientists posit that consciousness is related to the material brain.

We've all heard the stories about near-death experiences: the tunnel, the white light, the encounter with long-dead relatives now looking very much alive. Scientists have cast a skeptical eye on these accounts. They say that these feelings and visions are simply the result of a brain shutting down. But now some researchers are giving a closer neurological look at near-death experiences and asking: Can your mind operate when your brain has stopped?

'I Popped Up Out The Top Of My Head'

I met Pam Reynolds in her tour bus. She's a big deal in the music world — her company, Southern Tracks, has recorded music by everyone from Bruce Springsteen to Pearl Jam to REM. But you've probably never heard her favorite song. It's the one Reynolds wrote about the time she traveled to death's door and back. The experience has made her something of a rock star in the near-death world. Believers say she is proof positive that the mind can operate when the brain is stilled. Nonbelievers say she's nothing of the sort.

Reynolds' journey began one hot August day in 1991. "I was in Virginia Beach, Va., with my husband," she recalls. "We were promoting a new record. And I inexplicably forgot how to talk. I've got a big mouth. I never forget how to talk."An MRI revealed an aneurysm on her brain stem. It was already leaking, a ticking time bomb. Her doctor in Atlanta said her best hope was a young brain surgeon at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Arizona named Robert Spetzler.

"The aneurysm was very large, which meant the risk of rupture was also very large," Spetzler says. "And it was in a location where the only way to really give her the very best odds of fixing it required what we call 'cardiac standstill.' " It was a daring operation: Chilling her body, draining the blood out of her head like oil from a car engine, snipping the aneurysm and then bringing her back from the edge of death. "She is as deeply comatose as you can be and still be alive," Spetzler observes.- listen… [All Things Considered; npr player, 10 minutes 4 seconds]

Prayer May Reshape Your Brain.... and Your Reality

Third of a five-part series

Scientists are making the first attempts to understand spiritual experience — and what happens in the brains and bodies of people who believe they connect with the divine.

The field is called "neurotheology," and although it is new, it's drawing prominent researchers in the U.S. and Canada. Scientists have found that the brains of people who spend untold hours in prayer and meditation are different.

I met Scott McDermott five years ago, while covering a Pentecostal revival meeting in Toronto. It was pandemonium. People were speaking in tongues and barking like dogs. I thought, "What is a United Methodist minister, with a Ph.D. in New Testament theology, doing here?" Then McDermott told me about a vision he had had years earlier. "I saw fire dancing on my eyelids," he recalled, staring into the middle distance. "I felt God say to me, 'You be the oil, and I'll be the flame.' Then [I] began to feel waves of the Spirit flow through my body."

I never forgot McDermott. When I heard that scientists were studying the brains of people who spent countless hours in prayer and meditation, I thought, "I've got to see what's going on in Scott McDermott's head."

Focusing Affects Reality

A few years later, Andrew Newberg made that possible. Newberg is a neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania and author of several books, including How God Changes Your Brain. He has been scanning the brains of religious people like McDermott for more than a decade.

- listen… [All Things Considered; npr player, 8 minutes 7 seconds]

Are Spiritual Encounters All in Your Head?

Second of a five-part series

According to polls, there's a 50-50 chance you have had at least one spiritual experience — an overpowering feeling that you've touched God, or another dimension of reality.

So, have you ever wondered whether those encounters actually happened — or whether they were all in your head? Scientists say the answer might be both.

If you're looking for evidence that religion is in your head, you need look no further than Jeff Schimmel. The 49-year-old Los Angeles writer was raised in a Conservative Jewish home. But he never bought into God — until after he was touched by a being outside of himself.

"Yeah," Schimmel says, "I was touched by a surgeon."

About a decade ago, Schimmel had a benign tumor removed from his left temporal lobe. The surgery was a snap. But soon after that — unknown to him — he began to suffer mini-seizures. He'd hear conversations in his head. Sometimes the people around him would look slightly unreal, as if they were animated.

Then came the visions. He remembers twice, lying in bed, he looked up at the ceiling and saw a swirl of blue and gold and green colors that gradually settled into a shape. He couldn't figure out what it was.

"And then, like a flash, it dawned on me: 'This is the Virgin Mary!' " he says. "And you know, it's funny. I laughed about it, because why would the Virgin Mary appear to me, a Jewish guy, lying in bed looking at the ceiling? She could do much better."

- listen… [npr player, 8 minutes 5 seconds]

On God

Tuning in

I was sitting in a small examination room at Detroit’s Henry Ford Hospital when the question hit me with the force of a tank: Is the brain a radio, or a CD player? Not an elegant question, surely, but it has nipped at my heels for the past three years.

The conundrum offered itself as I was interviewing a man named Terrence Ayala at the hospital’s epilepsy clinic. Several years earlier, Ayala had undergone an operation that left him with a stuttering problem, and more. Often when falling asleep, but other times as well, he would sense a "dark presence," usually looming over him, as real and tangible as the chair he was sitting on.

The neurologists at Henry Ford suspected Ayala’s surgery had left scarring on his brain, which had eventually resulted in temporal lobe epilepsy. And in fact the epilepsy medications he had taken over the past few months had eviscerated this "sensed presence." But rather than relief, Ayala told me he felt robbed—as if someone had dismantled his bridge to the spiritual realm.

"We have a habit of trying to bring people into conformity through medication and modern science and all kinds of things," he observed. "Who knows what realities we’re medicating away?"

This begged another question in my mind: Are transcendent experiences—not just Terrence Ayala’s, but also Teresa of Ávila’s—merely a physiological event, or does the brain activity reflect an encounter with another dimension? This is where the CD vs. radio debate begins. Reductionists think that the brain is like a CD player. The content—the song, for example—is playing in a closed system, and if you take a hammer to the machine, then it’s impossible to hear the song. No God exists outside the brain trying to communicate; all spiritual experience is inside the brain, and when you destroy that, God and spirituality die as well.

Torture, Mind, and Body

Does torture inflict lasting psychological harm?

Yesterday we examined the CIA's reasons for involving psychologists in the Bush torture—sorry, I meant detainee interrogation program. The psychologist's job was to figure out how to inflict unbearable anguish on prisoners without requiring violence, or at least without leaving visible scars.

But what about mental scars?

In the Los Angeles Times, Sarah Gantz and Ben Meyerson look into the controversy:

The conclusion in recently released Justice Department memos that CIA interrogation techniques would not cause prolonged mental harm is disputed by some doctors and psychologists, who say that the mental damage incurred from the practices is significant and undeniable. ... Interrogation techniques undoubtedly have lasting effects, [professor Nina Thomas of NYU] said, such as paranoia, anxiety, hyper-vigilance and "the destruction of people's personalities." ... "Some of these [techniques] clearly have a very real physical component," said Dr. Allen Keller, director of the Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture. He cited waterboarding. ... A prisoner deprived of sleep may be overwhelmed with memories of torture when they become tired years later, Keller said. The same is true, he said, for the stomach growls of those tortured by starvation.

I'll go a step further. The problem isn't just that the techniques are physical. The problem is that the mind itself is physical. I just got back from a conference at Cambridge University sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation. In a series of seminars with neuroscientists and philosophers—among them, Chris Frith of University College London, Alva Noe of the University of California-Berkeley, and Fraser Watts of Cambridge—we explored how physiology, mental activity, and environmental conditions transform one another. You can't torture the mind without altering the brain. And since the brain is part of the body—in fact, the part of the body that most influences all the others—the marks you leave are pervasive. You can alter any physical process in which the mind is involved: sleep, eating, conversation, love, going out in public, or all of the above.

Three Sages / Three Paths

Aging is not what it used to be. Religion is not what it used to be. People are different, both physically and psychologically, from what they were even a generation ago. How, then, should we choose to age?

An aging rabbi (we shall meet him momentarily) was dismayed when he could no longer be the workaholic he'd always been - accomplishing, accomplishing. Search as he would, he could find no models to light the way for him in his post-sixtieth birthday bewilderment. The rabbi formulated the issue: We have been granted an extended lifetime, but we don't have an extended consciousness to make use of it.

The rabbi conjectured: Suppose religion could forge a new kind of awareness that could put to good use our extended lifespan? That would certainly be a new job description for religion. The three "sages" we shall meet here are pioneering just such new approaches to later life. They each consider aging at least as important for the soul as youth or middle age. They make "growing old" not a problem to be solved but an unlikely adventure - and an adventure that, even when far from easy, one would not want to miss.

ELDERS AWAKENING

When Reb Zalman retired from teaching at Temple University in 1987, he worried that retirement would retire him - from purpose, from life itself. I can't look forward, he thought, for that's where death waits. I can't look back, or my past mistakes will haunt me. And that doesn't leave much present, where things are now breaking down anyway.

Reb Zalman undertook a 40-day retreat to gain insight about what to do.

Emerging from the retreat, he wrote From Age-ing to Sage-ing: A Profound New Vision of Growing Older. If you do nothing else, the book says, try to do three things: (1) In the "October" of life (your mid-60s, say), heal your relation to your own past, to things left unresolved. For example, you could hold a (probably imaginary) banquet to honor your enemies, for their harms made you more aware. (2) In "November" (your 70s), you can better help ameliorate the society around you. He would like an Elder Corps established and sent to the world's troubled spots, to connect with their counterpart elders there. (3) Finally, in the "December" of your life, do the inner work to ensure a good completion. Sloughing off both fear and regret, you may heal "life" itself.

Save My Brain!

The mind, like the body, gets flabbier with age. Can a crash course in, well, anything, keep it in shape? We sent a boomer to One Day University to find the answer.

IT'S THE BRAIN THAT SETS US APART

from other creatures. That's why its decline fills us with dread - it foreshadows not just death, but also a shuffling toward being something less than human. We fear devolution. * My brain is my bond to the baby boom, to which I belong only demographically. I was born in 1964, the last year of the boom, so I feel like a Generation Xer. But I'm a boomer about my brain. * Baby boomers like to try to stave off the inevitable - inventor Ray Kurzweil even thinks he can beat death. So why should my brain slip? I regularly play Brain Age or Big Brain Academy, games that claim to keep my neurons firing. I try to drive different routes, to keep my brain from falling into a routine (it's never boring to get lost). I force myself to read things like Paradise Lost (a better exercise when my brain was younger). And, recently, I attended One Day University - after all, what could be better for my brain than a little schooling?One Day U offers sessions in various cities throughout the year, with each featuring four lectures on diverse topics, given by gifted teachers from top schools. The day I go, the profs come from Brown, Harvard, Syracuse, and Dartmouth. It's open to anyone (a cadre of high school students from Boston regularly attend), but it's clearly targeted at boomers, and we make up most of the class. We sit though four lectures of about 70 minutes each, including time for questions at the end.

The program, based in Northampton, bills itself as "the most stimulating day of college available anywhere." Sprinkle some salt on that: One Day U's cofounder and director, Steve Schragis, bankrolled Spy magazine back in the day. Schragis tells the several hundred of us gathered in our "classroom," an auditorium at Babson College in Wellesley, that "there is no homework, no exams, you can't fail, and you've already earned an A." Today's classes will be political science, psychology, history, and cosmology. I know something about all these things, and in two of them, I think I know quite a bit. But the only thing I care about is, will I feel brainier at the end of the day?

Flesh Made Soul

Can a new theory in neuroscience explain spiritual experience to a non-believer?

September 25, 1974. I am on the delivery table at a maternity hospital run by Swiss-German midwives in Bafut, Cameroon. My daughter, Abi, arrives at 1:30 a.m. but because no bed is available, I lie awake in the kerosene lamplight waiting for the dawn.

Mornings in this West African highland are chilly and calm. Swirls of woodsmoke carpet the ground. On a nearby veranda, the peace is shattered by the high-pitched ululations of a young woman. Her arms are raised above her head, bearing a tiny bundle. It is her dead infant. As she paces up and down, grieving, I reach for my sleeping newborn and hold her to my body, shaking.

The next morning, as dawn breaks, I am in a private room and again the ululations pierce the stillness. But this time the sounds convey elation. A grandmother walks the veranda, holding newborn twins–male firstborns–in her arms.

A birth, a death, more births. So close. Palpable. These transformative events somehow conspire to propel me, while sitting up in bed, into an altered state of consciousness. I am floating in a vast ocean of timelessness. My right hand holds my mother's hand. In her right hand is her mother's hand, which is holding her mother's hand and so on into the depths of time. My left hand holds my daughter's hand, which is holding her daughter's hand, who is holding her daughter's hand and so on into an infinite future.

Time stands still. My mind and body expand in a state of pure ecstasy. Again, I am floating. The spiritual experience envelops me–for how long I don't know–until I come back into my body and observe my baby by my side.

If It Feels Good to Be Good, It Might Be Only Natural

The e-mail came from the next room.

"You gotta see this!" Jorge Moll had written. Moll and Jordan Grafman, neuroscientists at the National Institutes of Health, had been scanning the brains of volunteers as they were asked to think about a scenario involving either donating a sum of money to charity or keeping it for themselves.

As Grafman read the e-mail, Moll came bursting in. The scientists stared at each other. Grafman was thinking, "Whoa—wait a minute!"

The results were showing that when the volunteers placed the interests of others before their own, the generosity activated a primitive part of the brain that usually lights up in response to food or sex. Altruism, the experiment suggested, was not a superior moral faculty that suppresses basic selfish urges but rather was basic to the brain, hard-wired and pleasurable.

Their 2006 finding that unselfishness can feel good lends scientific support to the admonitions of spiritual leaders such as Saint Francis of Assisi, who said, "For it is in giving that we receive." But it is also a dramatic example of the way neuroscience has begun to elbow

God Is in the Dendrites

Can “Neurotheology” Bridge the Gap between Religion and Science?

Looking back, it was the intellectual high point of my summer: Ten science and religion reporters sitting inside the divinity building at Cambridge University, contemplating the essence of a raisin. As the hypnotic voice of the speaker, an expert on Buddhist meditation, lulled us from the here and now, I placed the wrinkly thing on my tongue, exploring its peaks and valleys until, all of a sudden, I broke through the linguistic cellophane. The raisin ceased to be a raisin or anything with a name. It had no history as a fruit grown on a vine and shipped to market; it evoked no memories of the little Sun-Maid boxes my mother packed in my lunch pail or of a particularly good glass of cabernet sauvignon. It just was.

My colleagues–we were in England for a journalism fellowship sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation, which hopes to find God in science–were having their own quiet epiphanies. After days of talks by physicists and theologians seeking cosmological justification for their spiritual beliefs, the close encounter with the raisin brought us back to earth. God was not to be found in the perfect wheeling of the cosmos, the quantum ambiguity of the atom, or the fortuity of the Big Bang, but in the electrical crackling of the human brain.

If recent findings in "neurotheology" hold up, our meditating neurons, locked in the state called mindfulness, were radiating gamma waves at about 40 cycles per second, beating against the 50-hertz hum of the fluorescent lights. At the same time, parts

Call for "Neuroethics" as Brain Science Races Ahead

Neuroscientists are making such rapid progress in unlocking the brain’s secrets that some are urging colleagues to debate the ethics of their work before it can be misused by governments, lawyers or advertisers.

The news that brain scanners can now read a person’s intentions before they are expressed or acted upon has given a new boost to the fledgling field of neuroethics that hopes to help researchers separate good uses of their work from bad.

The same discoveries that could help the paralyzed use brain signals to steer a wheelchair or write on a computer might also be used to detect possible criminal intent, religious beliefs or other hidden thoughts, these neuroethicists say.

"The potential for misuse of this technology is profound," said Judy Illes, director of the Stanford University neuroethics program in California. "This is a truly urgent situation."

The new boost came from a research paper published last week that showed neuroscientists can now not only locate the brain area where a certain thought occurs but probe into that area to read out some kinds of thought occurring there.

Its author, John-Dylan Haynes of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, compared this to learning how to read books after simply being able to find them before. "That is a huge step," he said.

Haynes hastened to add that neuroscience is still far from developing a scanner that could easily read random thoughts.

Buddha on the Brain

Ex-monk B. Alan Wallace explains what Buddhism can teach Western scientists, why reincarnation should be taken seriously and what it's like to study meditation with the Dalai Lama.

B. Alan Wallace may be the American Buddhist most committed to finding connections between Buddhism and science. An ex-Buddhist monk who went on to get a doctorate in religious studies at Stanford, he once studied under the Dalai Lama, and has acted as one of the Tibetan leader's translators. Wallace, now president of the Santa Barbara Institute for Consciousness Studies, has written and edited many books, often challenging the conventions of modern science. "The sacred object of its reverence, awe and devotion is not God or spiritual enlightenment but the material universe," he writes. He accuses prominent scientists like E.O. Wilson and Richard Dawkins of practicing "a modern kind of nature religion."

In his new book, Contemplative Science: Where Buddhism and Neuroscience Converge, Wallace takes on the loaded subject of consciousness. He argues that the long tradition of Buddhist meditation, with its rigorous investigation of the mind, has in effect pioneered a science of consciousness, and that it has much to teach Western scientists. "Subjectivity is the central taboo of scientific materialism," he writes. He considers the Buddhist

Is There Room for the Soul?

New challenges to our most cherished beliefs about the human spirit

A mind is a tough thing to think about. Consciousness is the defining feature of the human species. But is it possible that it is also no more than an extravagant biological add-on, something not really essential to our survival? That intriguing possibility plays on my mind as I cross the plaza of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, a breathtaking temple of science perched on a high bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean in La Jolla, Calif. I have just visited the office of Terry Sejnowski, the director of Salk’s Computational Neurobiology Laboratory, whose recent research suggests that our conscious minds play less of a role in making decisions than many people have long assumed. "The dopamine neurons are responsible for telling the rest of the brain what stimuli to pay attention to," Sejnowski says, referring to the cluster of brain cells that produce one of the many chemical elixirs that activate, deactivate, or otherwise alter our mental state. In a deeper way, he explains, evolutionary factors—the need for individual organisms to survive, find food or a mate, and avoid predators—are at work behind the mechanisms of unconscious decision making. "Consciousness explains things that have already been decided for you," Sejnowski says. Asked whether that means that consciousness is only a bit player in the overarching drama of our lives, he admits that it’s hard to separate rationalizing from decision making. "But," he adds, "we might overrate the role of our consciousness in making decisions."

Overrated or underrated, consciousness is not being ignored these days. Indeed, during the past 20 years or so it has become the focus of an expanding intellectual industry involving the combined, but not always harmonious, efforts of neuroscientists, cognitive psychologists, artificial intelligence specialists, physicists, and philosophers.But what, exactly, has this effort accomplished? Has it brought us any closer to understanding how the physical brain is related to the

Divining the Brain

Andrew Newberg discusses what happens in our brains during prayer, meditation and mystical visions. Yet understanding the brain, argues the neuroscientist, does not close the book on the nature of religious experience.

Can we actually see God in the brain? Well, not exactly. But a few enterprising neuroscientists have found ways to detect and measure the varieties of our religious experience. Using brain scanning technology, researchers have been able to pinpoint which parts of the brain are activated during prayer and meditation. While they can't answer the biggest question of all–does God exist?–they are probing one of the deepest mysteries in science: the nature of consciousness.

They're also wading into a thorny issue in the science and religion debate: the connection between brain and mind. Most neuroscientists assume the mind is nothing more than electrochemical surges among nerve cells in the brain. But neuroscientists who study spirituality tend to be open to the possibility that the mind could exist independently of the brain. Some even question the materialist paradigm of science–-the idea that the only reality worth studying is what can be tested, quantified and reproduced. They wonder whether current scientific methods will ever be able to explain consciousness. But others are skeptical. Stephen Heinemann, president of the Society for Neuroscience, recently told the Chronicle of Higher Education, "I think the concept of the mind outside the brain is absurd."

One of the pioneers in the new field of neurotheology is Andrew Newberg, a 40-year-old physician at the University of Pennsylvania and director of the Center for Spirituality and the Mind, who has just published a book, Why We Believe What We Believe: Uncovering Our Biological Need for Meaning, Spirituality, and Truth, written with his colleague Mark Robert Waldman. Over the last decade, Newberg has conducted a series of brain-imaging studies of various spiritual practitioners, including Franciscan nuns, Buddhists and Pentecostal Christians who speak in tongues. His lab research has brought some surprising–and curious–results. For instance, during his study of Pentecostals, Newberg was amazed to see one of his own lab assistants start to sing and speak in tongues. It turned out that she had been doing it as part of her own religious practice for almost 10 years.

Plugged into the New Consciousness

We are, easily, the most connected and connective society of human beings ever. Our consciousness goes beyond individual minds. We are exquisitely aware. This is both our gem and our canker.

This piece is going to give readers their money’s worth.

We’ll start by floating a definition of consciousness—both startling and (I hope you’ll think) common sense.

On the way, we will consider some bemusing things about the new communications age in which we live.

And then—bam—we’re going to propose a morality of consciousness.

That’s what I call a Sunday morning’s walk.

Here’s my main theme: Consciousness is connectedness. Simple. Sweet. And it sings like the very cosmos. If it’s true, then you, I, and our society are rewiring ourselves and our worlds at breathtaking speed. And we need an ethics for it.

Last year, two scientists, Marcello Massimini and Giulio Tononi, performed what might at first seem a simpleminded experiment. They stimulated a number of awake subjects at a small, specific site in the brain. Then they measured where the stimulus went. It did rocket around in there. The awake brain does that: It can refer a single stimulus all over, connect different centers, serve different uses. Sometimes a stimulus ping-ponged around in there for as long as 300 milliseconds (almost a third of a second), a long time to bonk around for brain impulses, which can travel between

The Mind-Brain Problem

Psychologist Jerome Kagan Has Always Known that Biology Is Only a Partial Solution

Will the sum and substance of that evanescent phenomenon we call mind one day be completely understood in terms of the physical structure and functioning of the brain? Some philosophers and scientists think so. They believe that even the deepest puzzlements of the human psyche—awareness, the sense of self, and consciousness itself—will yield to the scientific investigations of neuronal circuitry and chemistry. Thanks to a host of new and ever-improving brain-monitoring and imaging technologies, we will come to see not only how brain architecture and activity correlate with consciousness but how they cause it—and even, if we agree with the philosopher Daniel Dennett, how they are it. If successful, this dazzling feat of reductionism will close the Cartesian mind-body divide and bring the intractable mind fully into the Darwinian paradigm, making the seat of the soul no less a mystery than any other highly evolved product of natural selection.

Or will it? As one might expect, dissenters and doubters abound. Among them, there is possibly no more interesting or qualified a skeptic than psychologist Jerome Kagan, a professor emeritus at Harvard University and the former director of its Mind/Brain/Behavior Interfaculty Initiative. In a career marked by works that have helped define and shape his still relatively young field—Change and Continuity in Infancy, The Nature of the Child, Galen’s Prophecy: Temperament in Human Nature, and Three Seductive Ideas are just a few of his titles—Kagan has been at the forefront of what is called the cognitive revolution in psychology. More to the point, he has been party to a major paradigm shift within his discipline. Simply put (and granting the existence of widely divergent schools within each broad paradigm), that shift has moved the field from an emphasis on nurture to one on nature, from Freudianism and behaviorism at one end to evolutionary psychology and neuroscience at the other.

The Deity in the Data

What the Latest Prayer Study Tells Us About God.

Brother, have you heard the bad news?

It was supposed to be good news, like the kind in the Bible. After three years, $2.4 million, and 1.7 million prayers, the biggest and best study ever was supposed to show that the prayers of faraway strangers help patients recover after heart surgery. But things didn’t go as ordained. Patients who knowingly received prayers developed more post-surgery complications than did patients who unknowingly received prayers—and patients who were prayed for did no better than patients who weren’t prayed for. In fact, patients who received prayers without their knowledge ended up with more major complications than did patients who received no prayers at all.

If the data had turned out the other way, clerics would be trumpeting the power of prayer on every street corner. Instead, the study’s authors and many media outlets are straining to brush off the results. The study "cannot address a large number of religious questions, such as whether God exists, whether God answers intercessory prayers, or whether prayers from one religious group work in the same way as prayers from other groups," the authors.

Bull. If these findings involved any other kind of therapy, doctors would spin hypotheses about the underlying mechanisms and why the treatment failed or backfired. And that’s exactly what theologians and scientists are doing as they try to explain away the data. They’re implicitly sketching possibilities as to what sort of God could account for the results. Here’s a list.

-

God doesn’t exist. This is the simplest explanation, favored by atheists. You pray, but nobody’s there, so nothing happens.

-

God doesn’t intervene. This is the view of self-limiting-deity theorists and of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. God may be there, but He’s not doing anything here.