Life Beyond Earth

The High Probability Of Finding 'Life Beyond Earth'

Scientific interest in extraterrestrial life has grown in the past 20 years. The field of astrobiology now includes researchers from a wide variety of disciplines — microbiologists studying bacteria that survive in the most extreme conditions on Earth; astronomers who believe there may be billions of planets with conditions hospitable to life; chemists investigating how amino acids and living organisms first appeared on Earth; and scientists studying rocks from Mars are seeing convincing evidence that microbial life existed on the Red Planet.

In First Contact: Scientific Breakthroughs in the Hunt for Life Beyond Earth, Marc Kaufman, a science writer and national editor at The Washington Post, explains how microbes found in some of Earth's most inhospitable environments may hold the key to unlocking mysteries throughout the solar system.

Kaufman talks with Fresh Air's Dave Davies about the ongoing search for life in the universe — from current research, to the unknowns in the field.

"There are undoubtedly billions or trillions of planets out there and there are most likely billions in the Milky Way itself — just one of billions of galaxies," Kaufman says. "There are billions of planets in habitable zones in relation to their stars that would allow for water to be liquid and for other important conditions for life."

listen now or download NPR's Fresh Air from WHYY

First Contact

Scientific Breakthroughs in the Hunt for Life Beyond Earth

If it's just us in this universe, what a terrible waste of space.

But it's not. Before the end of this century, and perhaps much sooner than that, scientists will determine that life exists elsewhere in the universe. This book is about how they're going to get there. And when they do, that discovery will rival the immensity of those that launched our previous sci entific revolutions and, in the process, defined our humanity. Copernicus and Galileo told us we were not, after all, at the center of the universe, and their ideas fathered a scientific astronomy that, four hundred years later, is allowing us to be a space-faring planet. Charles Darwin gave us our evo lutionary roots, which, a century later, propelled Louis and Mary Leakey on a thirty-year search culminating in the recovery of fossil hominid re mains almost two million years old in Tanzania's Olduvai Gorge — proof that humankind began in Africa. So here we are now, the descendants of the skilled toolmakers and explorers who left the continent some sixty to seventy thousand years ago. We've populated the globe and sent astronauts to the moon. Next up: Life beyond Earth.

For thousands of years, humans have wondered about who and what might be living beyond the confines of our planet: gods, beneficent or angry, a heaven full of sinners long forgiven, creatures as large and strange as our imagination. Scientists now are on the cusp of bringing those mus ings back to Earth and recasting our humanity yet again. "Astrobiology" is the name of their young but fast-growing field, which immodestly seeks to identify life throughout the universe, partly by determining how it began on our planet. The men and women of astrobiology — an iconoclastic lot, quite unlike the caricatures of geeks in white lab coats or UFO-crazed con spiracy theorists — are driven by a confidence that extraterrestrial creatures are there to be found, if only we learn how to find them. Most hold the conviction that if a form of independently evolved life, even the tiniest mi crobe, is detected below the surface of Mars or Europa, or other moons of Jupiter or Saturn, then the odds that life does exist elsewhere in our galaxy and potentially in billions of others shoot up dramatically. A solar system that produces one genesis — ours — might be an anomaly. A single solar system that produces two or more geneses tells us that life can begin and evolve whenever and wherever conditions allow, and that extraterrestrial life may well be an intergalactic commonplace.

Contact: The Day After

If we are ever going to pick up a signal from E.T., it is going to happen soon, astronomers say. And we already have a good idea how events will play out

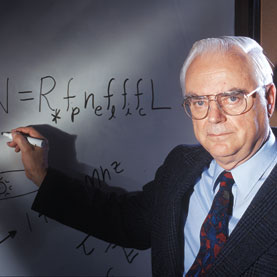

One day last spring Frank Drake returned to the observatory at Green Bank, W.Va., to repeat a search he first conducted there in 1960 as a 30-year-old astronomer. Green Bank has the largest steerable telescope in the world—a 100-meter-wide radio dish. Drake wanted to aim it at the same two sunlike stars he had observed 50 years ago, Tau Ceti and Epsilon Eridani, each a bit more than 10 light-years from Earth, to see if he could detect radio transmissions from any civilizations that might exist on planets orbiting either of the two stars. This encore observing run was largely ceremonial for the man who pioneered the worldwide collaborative effort known as SETI—the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. As a young man, Drake had half-expected to find a cosmos humming with the equivalent of ET ham radio chatter. The elder Drake did not expect any such surprises from Tau Ceti or Epsilon Eridani. The Great Silence, as some astronomers call the absence of alien communiqués, remains unbroken after five decades of searching. And yet so does Drake’s conviction that it is only a matter of time before SETI succeeds.

"Fifty years ago, when I made the first search, it took two months—200 hours of observing time at Green Bank," says Drake, who is now chairman emeritus at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif. "When I went back this year, they gave me an hour to repeat the experiment. That turned out to be way too much time. It took eight tenths of a second—each star took four tenths of a second! And the search was better. I looked at the same two stars over a much wider frequency band with higher sensitivity and more channels, in eight tenths of a second. That shows how far we’ve come. And the rate of improvement hasn’t slowed down at all."

Not "Life," but Maybe "Organics" on Mars

Thirty-four years after NASA's Viking missions to Mars sent back results interpreted to mean there was no organic material - and consequently no life - on the planet, new research has concluded that organic material was found after all.

The finding does not bring scientists closer to discovering life on Mars, researchers say, but it does open the door to a greater likelihood that life exists, or once existed, on the planet.

"We can now say there is organic material on Mars, and that the Viking organics experiment that didn't find any had most likely destroyed what was there during the testing," said Rafael Navarro-Gonzalez of the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

"For decades NASA's mantra for Mars was 'follow the water' in the search for life, and we know today that water has been all over the planet," he said. "Now the motto is 'follow the organics' in the search for life."

The original 1976 finding of "no organics" was controversial from the start because organic matter - complex carbons with oxygen and hydrogen, which are the basis of life on Earth - is known to fall on Mars, as onto Earth and elsewhere, all the time. Certain kinds of meteorites are rich in organics, as is the interstellar dust that falls from deep space and blankets planets.

The new results, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Planets and highlighted Friday in a NASA news release, flow directly from a discovery made by NASA's Phoenix lander in 2008.

Ancient Meteorite Heats Up Martian Life-Form Debate

LEAGUE CITY, Texas — NASA’s Mars Meteorite Research Team reopened a 14-year-old controversy on extraterrestrial life last week, reaffirming and offering support for its widely challenged assertion that a 4-billion-year-old meteorite that landed thousands of years ago on Antarctica shows evidence of microscopic life on Mars.

The scientists reported that additional Martian meteorites appear to house distinct and identifiable microbial fossils that point even more strongly to the existence of life.

"We feel more confident than ever that Mars probably once was, and maybe still is, home to life," team leader David McKay said at a NASA-sponsored conference on astrobiology.

The researchers’ presentations were not met with any of the excited frenzy that greeted the original 1996 announcement about the meteorite — which led to a televised statement by President Bill Clinton in which he announced a "space summit," the formation of a commission to examine its implications and the birth of a NASA-funded astrobiology program.

Fourteen years of relentless criticism have turned many scientists against the McKay results, and the Mars meteorite "discovery" has remained an unresolved and somewhat awkward issue. This has continued even though the team’s central finding — that Mars once had living creatures — has gained broad acceptance among the biologists, chemists, geologists, astronomers and other scientists who make up the astrobiology community.

Aliens Calling

Where is ET and should he have not called by now? Tracey Logan asks exactly that question after speaking to the top scientists hunting for proof of alien life. She went to the Royal Society in London where the possibility of detection of extra-terrestrial life, and its consequences for science and society, were discussed.

listen now or download mp3 format, 6 min 15 secs

When E.T. Phones the Pope

The Vatican investigates all God's creatures, green and small.

ROME -- A little more than a half-mile from the Vatican, in a square called Campo de' Fiori, stands a large statue of a brooding monk. Few of the shoppers and tourists wandering through the fruit-and-vegetable market below may know his story; he is Giordano Bruno, a Renaissance philosopher, writer and free-thinker who was burned at the stake by the Inquisition in 1600. Among his many heresies was his belief in a "plurality of worlds" -- in extraterrestrial life, in aliens.

Though it's a bit late for Bruno, he might take satisfaction in knowing that this week the Vatican's Pontifical Academy of Sciences is holding its first major conference on astrobiology, the new science that seeks to find life elsewhere in the cosmos and to understand how it began on Earth. Convened on private Vatican grounds in the elegant Casina Pio IV, formerly the pope's villa, the unlikely gathering of prominent scientists and religious leaders shows that some of the most tradition-bound faiths are seriously contemplating the possibility that life exists in myriad forms beyond this planet. Astrobiology has arrived, and religious and social institutions -- even the Vatican -- are taking note.

Father Jose Funes, a Jesuit astronomer, director of the centuries-old Vatican Observatory and a driving force behind the conference, suggested in an interview last year that the possibility of "brother extraterrestrials" poses no problem for Catholic theology. "As a multiplicity of creatures exists on Earth, so there could be other beings, also intelligent, created by God," Funes explained. "This does not conflict with our faith because we cannot put limits on the creative freedom of God."

Yet, as Bruno might attest, the notion of life beyond Earth does not easily coexist with the "truths" that many people hold dear. Just as the Copernican revolution forced us to understand that Earth is not the center of the universe, the logic of astrobiologists points

Exploring the Multiverse

Do quantum computers offer proof of parallel universes? And where does that leave philosophers?

The concept of the multiverse is not new. In 55 BC, Lucretius speculated that the motion of atoms might be energetic enough to propel them into parallel worlds. During the Renaissance, Giordano Bruno raised a similar possibility, his speculations causing him tragic trouble with the church. The poet, Thomas Traherne, raised the thought again in the 17th century: God's love is infinite, he mused, so maybe there are an infinite number of worlds over which that love moves.

The history of the idea is worth bearing in mind since it suggests something: the multiverse proposal appears when the cosmology of the day reaches a limit of understanding.

Today, it arises in a number of contexts. Consider just one, the way it tackles a paradox of quantum theory. The quantum world is described as a superposition of states, expressed by the wave function. However, we don't live in a superposition of states, but just one. The paradox is how the two relate. In the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, the wave function is said spontaneously and mysteriously to collapse into the state we actually observe. John Gribbin, the popular science writer who has a new book out, In Search of the Multiverse, rejects that. Instead, he follows Hugh Everett and David Deutsch who have argued that in the superposition of states, the wave function actually describes the parallel worlds of a multiverse.

What we experience, then, is just one part of the wave function, other parts existing in other universes. So, in the famous Schrödinger's Cat thought experiment, it is not that the cat lives or dies according to the choice of an observer. Rather, it is that there is one universe in which the cat lives, and another in which it never lived.

Gribbin familiarises the possibility by appealing to the sci-fi trope of parallel universes in which, say, I never wrote this article, and another again in which you never read it. You can then have fun asking which universe you'd prefer to be in. Perhaps there is even a universe in which everyone on Cif threads cordially and routinely agrees.

God or a Multiverse?

Does modern cosmology force us to choose between a creator and a system of parallel universes?

Is there a God or a multiverse? Does modern cosmology force us to choose? Is it the case that the apparent fine-tuning of constants and forces to make the universe just right for life means there is either a need for a "tuner" or else a cosmos in which every possible variation of these constants and forces exists somewhere?

This choice has provoked anxious comment in the pages of this week's New Scientist. It follows an article in Discover magazine, in which science writer Tim Folger quoted cosmologist Bernard Carr: "If you don't want God, you'd better have a multiverse."

Even strongly atheistic physicists seem to believe the choice is unavoidable. Steven Weinberg, the closest physics comes to a Richard Dawkins, told the eminent biologist: "If you discovered a really impressive fine-tuning ... I think you'd really be left with only two explanations: a benevolent designer or a multiverse."

The anxiety in the New Scientist stems in part from the way this apparent choice has been leapt upon by the intelligent design people. Scientists don't like that since it seems to suggest that ID offers a theory that cosmologists are taking seriously. It doesn't of course: ID wasn't science before the multiverse hypothesis gained prominence, just a few years ago; and it hasn't become science since.

Further, if you bow to ID, the implication is that science should brush certain ideas under the carpet just because its ideological opponents find false succour in them. Physics has already learnt not to do that: some cosmologists ignored the hypothesis of a big bang for a while, believing it lent credence to the account of creation in the Bible. The big bang, though, turned out to be hugely more likely than the steady state theory that preceded it. The correct stance is to recognise that reading creation myths as scientific theory is just a category mistake.

Which is precisely why the choice between God or a multiverse is false too. If divinity is an explanation for anything, it is not a scientific explanation. A scientific explanation is precisely that, an explanation from within the laws of science. God, for believers, is the condition without which science cannot even get going; divinity is a final explanation for the laws of science, as a philosopher of religion would say.

To confuse the two is the fundamental theological mistake made by ID. It is also why you could have God and a multiverse without creating any significant theological problems. Believers don't have to choose. They can have both if they want.

- read more…

Science's Alternative to an Intelligent Creator: the Multiverse Theory

Our universe is perfectly tailored for life. That may be the work of God or the result of our universe being one of many.

A sublime cosmic mystery unfolds on a mild summer afternoon in Palo Alto, California, where I've come to talk with the visionary physicist Andrei Linde. The day seems ordinary enough. Cyclists maneuver through traffic, and orange poppies bloom on dry brown hills near Linde's office on the Stanford University campus. But everything here, right down to the photons lighting the scene after an eight-minute jaunt from the sun, bears witness to an extraordinary fact about the universe: Its basic properties are uncannily suited for life. Tweak the laws of physics in just about any way and–in this universe, anyway–life as we know it would not exist.

Consider just two possible changes. Atoms consist of protons, neutrons, and electrons. If those protons were just 0.2 percent more massive than they actually are, they would be unstable and would decay into simpler particles. Atoms wouldn't exist; neither would we. If gravity were slightly more powerful, the consequences would be nearly as grave. A beefed-up gravitational force would compress stars more tightly, making them smaller, hotter, and denser. Rather than surviving for billions of years, stars would burn through their fuel in a few million years, sputtering out long before life had a chance to evolve. There are many such examples of the universe's life-friendly properties–so many, in fact, that physicists can't dismiss them all as mere accidents.

"We have a lot of really, really strange coincidences, and all of these coincidences are such that they make life possible," Linde says.

Search for Alien Life Gains New Impetus

When Paul Butler began hunting for planets beyond our solar system, few people took him seriously, and some, he says, questioned his credentials as a scientist.

That was a decade ago, before Butler helped find some of the first extra-solar planets, and before he and his team identified about half of the 300 discovered since.

Biogeologist Lisa M. Pratt of Indiana University had a similar experience with her early research on “extremophiles”, bizarre microbes found in very harsh Earth environments. She and colleagues explored the depths of South African gold mines and, to their great surprise, found bacteria sustained only by the radioactive decay of nearby rocks.

“Until several years ago, absolutely nobody thought this kind of life was possible—it hadn’t even made it into science fiction,” she said. “Now it’s quite possible to imagine a microbe like that living deep beneath the surface of Mars.”

Discoveries Out There Require Preparation Right Here

Reports in 1996 that a meteorite from Mars that was found in Antarctica might contain fossilized remains of living organisms led then-Vice President Al Gore to convene a meeting of scientists, religious leaders and journalists to discuss the implications of a possible discovery of extraterrestrial life.

Gore walked into the room armed with questions on notecards but, according to MIT physicist and associate provost Claude R. Canizares, he put them down and asked this first question: What would such a discovery mean to people of faith?

There was silence, and then DePaul University president Jack Minogue, a priest, said: "Well, Mr. Vice President, if it doesn't sing and dance, we don't really have to worry much from a missionary point of view."

Everyone had a good laugh, and then moved on to the serious business of exploring the consequences of such a historic and unsettling discovery -- a discussion that continued for two hours.

Most scientists now discount the meteorite as evidence of Martian life, but preparing the public for a more definitive announcement continues. Several conferences and three major workshops have been held, the most recent sponsored by NASA, the John Templeton Foundation and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Its report, called "Philosophical, Ethical, and Theological Implications of Astrobiology," was published last year.

"Any discovery of extraterrestrial life would raise some challenging questions -- about the origin of life on Earth as well as elsewhere, about the centrality of humankind in the universe, and about the creation story in the Bible," said Connie Bertka, a Unitarian minister with a background in Martian geology who ran the workshops for the AAAS.

"The group felt strongly that the general public needs to know more about this whole subject and what astrobiology is trying to do," she said.

Stephen J. Dick, NASA's chief historian and a member of the NASA-sponsored panel and another private effort, said he thinks that all the Abrahamic religions would have to adapt, "because the relationship of God and man is so central, and the idea that man was made in God's image and put on Earth is so strong."

If life exists elsewhere, he said, then why would life on Earth be paramount to a creator? "A God that created the Earth and life on other Earths would still be majestic, but the logic of Him being someone to pray to and to get salvation from diminishes," he said.

Searching for Extraterrestrial Life

Washington Post staff writer Marc Kaufman and planet-hunter Paul Butler went online to discuss the search for alien life.

Washington Post staff writer Marc Kaufman and planet-hunter Paul Butler were online Monday, July 21 at 11 a.m. ET to discuss the search for alien life.

Butler, who discovered some of the first extra-solar planets, will be joining the discussion from the Keck Observatory in Hawaii after a night of sky gazing.

Kaufman notes in his story, Search for Alien Life Gains New Impetus, that there is an explosion taking place in astrobiology, in part because of NASA’s Phoenix landing on Mars.

"Few believe that the discovery of extraterrestrial life is imminent," writes Kaufman, "However, just as scientists long theorized that there were planets orbiting other stars—but could not prove it until new technologies and insights broke the field wide open—many astrobiologists now see their job as to develop new ways to search for the life they are sure is out there."

Arthur C. Clarke: The Science and the Fiction

Sixty years ago this month, in October 1945, the magazine Wireless World published an article by a relatively unknown writer and rocket enthusiast. Its title was: "Extra-Terrestrial Relays: Can Rocket Stations Give World Wide Radio Coverage?" Today, the author's name is known throughout the world. He is the science fiction writer Arthur C Clarke, and his prediction of satellite communications has come true in ways even he never imagined. To mark the anniversary, Heather Couper travels to Sir Arthur's home in Sri Lanka to hear his own story.

- listen… [hosted at www.bbc.co.uk, RealPlayer required]

Arthur C Clarke Still Looking Forward

It was 60 years ago this month that the popular magazine Wireless World published an article entitled Extra-terrestrial Relays: Can rocket stations give worldwide radio coverage? The author was a young writer by the name of Arthur C Clarke. His "rocket stations" are today known as communications satellites.

Eighty-seven years and the after-effects of polio have left Sir Arthur in a wheelchair and somewhat forgetful of past events; but as a science visionary, he is as sharp as ever, looking forward to the time when other predictions he has made come true.

He is convinced that we will become a space-faring species.

That people have not been back to the Moon for more than 30 years he regards as merely a temporary glitch.

As he points out in a special documentary on BBC Radio 4 this Wednesday, some of the greatest explorations in history were not followed up for decades.

He is sure that we will journey to Mars and eventually on to other solar systems; first sending robot probes, then humans, perhaps in suspended animation or even with their thoughts and consciousness transferred into a machine.

"When their bodies begin to deteriorate", he says, "you just transfer their thoughts, so their personalities could be immortal. You just save their thoughts on a disc and plug it in, simple!" he says, with a characteristic grin.

'Crazy' idea

Clarke grew up on a farm near Minehead, Somerset. His memories of that time are becoming hazy, but his younger brother, Fred, who still lives in the area, remembers the times well.

Arthur, he says, used to slip out from school in the lunch-break to search for copies of science fiction magazines, such as Astounding Stories.