Before & After 9-11

Defining the 'All-American Muslim'

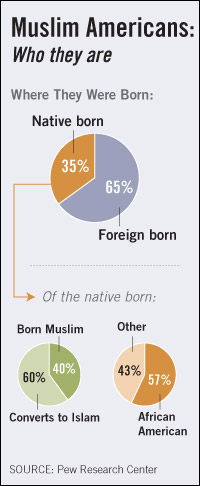

The story of Islam in America today is a story of rapid assimilation and even secularization.

Earlier this month, the TLC network announced that it will cancel the reality show "All-American Muslim" due to low ratings. Critics had complained that the show whitewashed the problem of Islamic radicalism in the U.S. by not portraying Muslim extremists, which led major sponsors such as the retailer Lowe's to drop their support.

But the show's producers were closer to portraying reality than critics asserted. The story of Islam in America today is a story of rapid assimilation and even secularization, not growing radicalism.

Jihad Turk, director of religious studies at LA's Islamic Center of Southern California, says that of the roughly 750,000 Muslims living in Southern California, just 30,000, or about 4%, regularly attend Friday prayer. And when I interview members of the center's offshoot, the Muslim Establishing Communities of America (MECA), whose target demographic is unaffiliated young adults, they say there are few Muslim institutions where they feel comfortable.

Younger Muslims say they don't like the gender segregation at prayers and the imams imported from other countries who repeat the same Friday sermons, known as Khutbahs, week after week. (There are only so many times I want to hear the hadith about how smiling is a kind of charity, one woman told me.) They question the religious education they received growing up, where they learned enough Arabic to recite prayers or Koranic verses but not enough to understand what they were saying. Many say they have disaffected friends who have fallen away from the faith.

Mosque attendance is not the only measure of religious observance, but Muslims are experiencing other signs of secularization as well. They are intermarrying at rates comparable to those of other religious groups in America. The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life estimates that about one in five Muslims is wedded to someone of another faith.

Gaddafi's Secret Missionaries

(Reuters) - On a tidy campus in his capital of Tripoli, dictator Muammar Gaddafi sponsored one of the world's leading Muslim missionary networks. It was the smiling face of his Libyan regime, and the world smiled back.

The World Islamic Call Society (WICS) sent staffers out to build mosques and provide humanitarian relief. It gave poor students a free university education, in religion, finance and computer science. Its missionaries traversed Africa preaching a moderate, Sufi-tinged version of Islam as an alternative to the strict Wahhabism that Saudi Arabia was spreading.

The Society won approval in high places. The Vatican counted it among its partners in Christian-Muslim dialogue and both Pope John Paul and Pope Benedict received its secretary general. Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, spiritual head of the world's Anglicans, visited the campus in 2009 to deliver a lecture. The following year, the U.S. State Department noted approvingly how the Society had helped Filipino Christian migrant workers start a church in Libya.

But the Society had a darker side that occasionally flashed into view. In Africa, rumors abounded for years of Society staffers paying off local politicians or supporting insurgent groups. In 2004, an American Muslim leader was convicted of a plot to assassinate the Saudi crown prince, financed in part by the Society. In 2011, Canada stripped the local Society office of its charity status after it found the director had diverted Society money to a radical group that had attempted a coup in Trinidad and Tobago in 1990 and was linked to a plot to bomb New York's Kennedy Airport in 2007.

Now, with the Gaddafi regime gone, it is possible to piece together a fuller picture of this two-faced group. Interviews with three dozen current and former Society staff and Libyan officials, religious leaders and exiles, as well as analysis of its relations with the West, show how this arm of the Gaddafi regime was able to sustain a decades-long double game.

Yet Libya's new leaders, the same ones who fought bitterly to overthrow Gaddafi and dismantle his 42-year dictatorship, are unanimous in wanting to preserve the WICS. They say they can disentangle its religious work from the dirty tricks it played and retain the Society as a legitimate religious charity - and an instrument of soft power for oil-rich Libya.

A committee led by a leading anti-Gaddafi Islamic scholar, Sheikh Al Dokali Mohammed Al Alem, is now investigating the Society's activities. Their report may take months to appear, but a Reuters investigation has found Libyan officials in Tripoli now say openly what under Gaddafi was taboo - that the religious Society was allied to a huge shadow network, especially in Africa.

"There are still some loose ends in the Islamic Call Society in Africa," said Noman Benotman, a former member of an al-Qaeda-linked Libyan Islamist group who now works on deradicalization of jihadists at the Quilliam Foundation in London.

"They still have a lot of money going around through these channels that used to belong to the Islamic Call Society," he said. "Huge amounts of money are involved. I think we're talking about one to two billion dollars."

Book Notes: Islam's Quantum Question

There have been several books published recently touting the historical contributions of Islamic scholars to the early history of science (in the Middle Ages), but fewer assessing the relationship between Muslim tradition and the challenges that modern science presents to it today.

Nidhal Guessoum, an astronomer at the American University of Sharjah, takes on this daunting task with his engaging book, Islam’s Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science.

American readers familiar with the seemingly interminable "debates" between creationists and biologists on evolution, will not be surprised to find that many Muslims, depending on their background, also reject Darwin.

But as Guessoum reveals, Islamic attitudes to science are more complex (and also more frustrating), depending on the subject. I was surprised, for example, to read that the Iranian mullahs had no problem approving embryonic stem cell research. But it turns out Muslim tradition has always been fairly liberal in its interpretation about the point at which a fetus can be considered fully human.

On the other hand, as Guessoum attests from his own experience, getting officials from any two Muslim countries to agree about the role modern astronomy should play in the correct determination of the new moon, for prayer purposes, can be a daunting task.

Just over four hundred pages, Islam’s Quantum Question is organized into three sections. The first reviews Islam, the Qur’an and its attitude toward science, both historically and in the present.

Well aware of his audience, Guessoum’s chapters in this first section include several brief bios of historic and recent Islamic philosophers and scientists and their views on how Muslim societies should regard pure science and the applications of technology. The gamut runs from the urgent call to embrace modern science–to warnings that a truly Islamic science needs to avoid the presuppositions of the Western tradition.

The second section discusses modern debates on evolution, cosmology and teleology–and how Muslim intellectuals have responded to these issues. It’s startling, for example, to read about the highly regarded Pakistani philosopher and poet, Muhammad Iqbal, a devoutly religious mystic, who dismissed two classic Western arguments for the existence of God–as a complete waste of time.

Catholics and Muslims Pursue Dialogue Amid Mideast Tension

Only five years ago, critical remarks by Pope Benedict about Islam sparked off violent protests in several Muslim countries. Never very good, relations between the world’s two largest religions sank to new lows in modern times.

This week, while protesters in the Arab world were demanding democracy and civil rights, Catholics and Muslims met along the Jordan River for frank and friendly talks about their differences and how to get beyond their misunderstandings.

The Catholic-Muslim Forum, which grew out of the tensions following Benedict’s speech in the German city of Regensburg, was overshadowed by events in Egypt, Yemen and Syria. The lack of any dramatic news here reflected the progress the two sides have made since 2006.

"We have passed from formal dialogue to a dialogue between friends," Cardinal Jean-Louis Tauran, head of the Vatican’s department for interfaith dialogue, said at the conference held near the Jordan River site believed to be where Jesus was baptised. "We realised that we have a common heritage,"

Recalling the strains that prompted Muslims to suggest a dialogue in 2007, Jordan’s Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad bin Talal said: "Since then, despite some misunderstandings, I dare say the general Muslim-Catholic ambiance has ameliorated considerably."

The 24 Catholic and 24 Muslim religious leaders, scholars and educators meeting here debated how each religion uses reason to strengthen insight into its beliefs. Roman Catholicism has long argued that faith without reason can breed superstition while nihilism can emerge from reason without faith.

POPE'S ILL-FATED SPEECH

This was the core message of Benedict’s Regensburg speech, but it was drowned out when he quoted a 14th century Byzantine emperor describing Islam as violent and irrational. Radical Islamists responded with violent protests.

The Importance of Understanding Religion in a Post-9/11 World

It’s hard to remember now, but in the days immediately following the attacks of 9/11, a spirit of religious unity reigned. Shocked political foes gathered together at the Washington National Cathedral for a prayer service that included a Muslim imam who read verses from the Koran. Just a few days later, George W. Bush quoted from the Koran himself at the Islamic Center in Washington, and told the country that "Islam is peace."

It didn’t take long, however, for the tender feelings of togetherness and tolerance to be replaced by division and hostility. Some thought leaders and policymakers embraced Samuel Huntington’s idea that the West was engaged in a "clash of civilizations" with Islam. Meanwhile, neo-atheists led by Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens put forward their own theory of a world split between civilized secularists and dangerous religionists. Secular academics and other thinkers have predicted and hoped for decades that as societies become more advanced, religion and its institutions would become less relevant. To them, 9/11 was further proof that religion is incompatible with modernity.

But while the last 10 years have inspired many difficult discussions about the relationship between religious communities and democratic societies, they have also proven that the decline of religion is not inevitable in modern society. Trust in religious institutions and leaders has fallen, as it has for secular institutions as well. But Americans continue to value religion–85% consistently tell Pew pollsters that religion is an important part of their lives. And the relocation of religious immigrants to the U.S. and parts of Europe has insured that the West is by no means a civilization in which religion is invisible. We read most often about the conflicts that occur in our modern communities over religion: the banning of hijab in France, fights over plans for an Islamic center in lower Manhattan, debates over the teaching of evolution in public schools. But in our focus on these conflicts, we too often miss something fascinating that is going on. Ancient religious traditions are not fading away in the face of modernity. They are adapting–and forcing modern societies to adapt to them as well. High school football players in Dearborn, Michigan, schedule midnight practices during Ramadan. Conservative Christians study political theory and snag competitive internships in Washington. Christian Scientists lobby Congress and win provisions to cover their practitioners in health reform.

And the wishful thinking of the neo-atheists ignores the fact that a little religion often does a lot of good. The British psychiatrist Russell Razzaque, a Muslim, has studied jihadists and discovered that many came from families that were not terribly religious. Their lack of familiarity with the Koran and Muslim teachings left them vulnerable to the distorted version of Islam that radicalists preached. By contrast, those potential recruits like Razzaque who grew up in religious homes knew enough about the Koran to recognize that something was off about the jihadist message.

Feriha Peracha on Rescuing Taliban Child Soldiers

Pakistani psychologist Feriha Peracha directs an experimental school designed to de-radicalize Taliban boy soldiers. She says many of her young students were forcibly recruited to the Taliban and trained to wear suicide vests. Now, they're ready to go home again.

listen now or download To the Best of our Knowledge

Why 9/11 Was Good for Religion

9/11 strengthened fundamentalism in every global faith – and in atheism too. But it has also led to backlashes against these doctrines wherever they have appeared. In Islam there have been positive developments. The attacks were repeatedly and clearly condemned by Muslim leaders all over the world. After Pope Benedict XVI's controversial Regensburg speech, the most notable response was the decision of 137 Muslim scholars to sign a declaration outlining what common values they shared with Christians.

This "common word" declaration is an example of "hard tolerance" – the increasing practice of making theological differences distinct and then talking about them, rather than trying to conceal them in a syrup of platitudes about love and mysticism. The aim is for priests, imams and rabbis to enter imaginatively into each other's ideologies, rather than simply agreeing.

At the same time, the heretical understanding of jihad as the sixth pillar of Islam, which originated in Egyptian circles in the 1980s, spread across south-east Asia. Children in the disputed areas of Pakistan are taught by the Taliban that jihad can compensate for other flaws in a Muslim's life.

Among Christians, too, there has been a growth of understanding and interest in Islam, and a simultaneous increase in its demonisation, which this year culminated in Anders Breivik's terrorist attacks in Norway. The mass killer was clearly influenced by a post-9/11 theology that sees Christian Europe under attack from Muslim immigration. Variants of this idea animate political parties in many European countries: the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Italy. For them, Europe's Christian identity has become a sacred value.

The same polarised reactions can be seen in secular ideologies. The new atheist movement was started by a group of writers who perceived Islam as an existential threat. "We are at war with Islam," argued one of its leaders, Sam Harris, who also called for the waterboarding of al-Qaida members. Meanwhile The God Delusion author, Richard Dawkins, refers to Islam as the most evil religion in the world. The publication of anti-Muhammad cartoons in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten in 2005, and the furore surrounding it, demonstrated the deliberate use of blasphemy as a weapon in cultural wars.

At the same time, secular governments across Europe have made increasing efforts to understand and accommodate religious sensibilities. As welfare states come to seem increasingly expensive, many have turned more and more towards religion to deliver social services. Whatever happens, it appears the idea that religion is doomed and disappearing was buried in the rubble of the twin towers. "9/11 was good for business" says Scott Appleby, professor of history at Notre Dame University. "For many people, we told people that religion is really important and that the secularisation theory, which had been very fashionable, was wrong."

Defusing Radical Faith

CAMBRIDGE, England (Reuters) - When Henry Kissinger published "Diplomacy," his study of international relations, in 1994, it had no index entries for Islam or religion.

Ten years later, another secretary of state, Madeleine Albright, wrote her own study on world affairs: "The Mighty and the Almighty: Reflections on America, God and World Affairs." Almost half the book dealt with Muslims and Islam.

The contrast between the two books highlights the way the world changed after 19 Muslims flew hijacked planes into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and a Pennsylvania field on September 11, 2001.

The attacks brought religion back into public affairs for many western countries where faith had largely faded into the private sphere.

"9/11 showed religion can no longer be ignored," Scott Appleby, a historian at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, told a seminar on religion after September 11 at Cambridge University.

"It is a critical element in many national systems and in radical and extremist movements, but also in movements oriented to human rights, peace-building and civil society," he said.

Since that day, governments and researchers in North America and Europe have turned to sociology, psychology, anthropology and other disciplines trying to understand religiously motivated violence and work out how to prevent it.

"SECULAR MYOPIA"

The results are mixed. Religion's exact role in radicalism is unclear. Psychology and group dynamics may drive extremists more than faith. The Arab Spring could become a democratic option that trumps the jihadist ideology of al Qaeda.

For decades before September 11, policymakers and analysts in western countries exhibited what Appleby called a "secular myopia" about religion in politics. Since faith was supposed to be private, they mostly left it out of their analyses. This happened despite the fact that ultra-conservative religious movements had appeared in many world faiths in those years and were often reflected in political action.

Clergy Insulted by Speaking Ban on 9/11

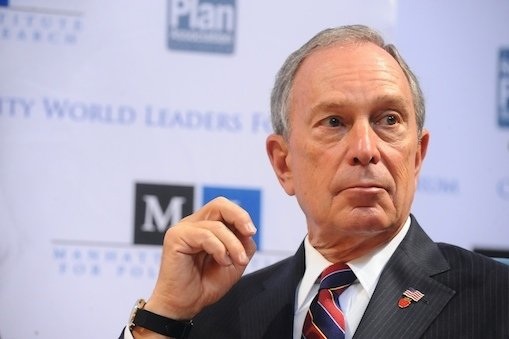

Mayor Michael Bloomberg is banning clergy-led prayer at events marking the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. The mayor's office says he wants to avoid disagreements. Some religious groups call the ban a sign of prejudice against religion.

DAVID GREENE, host:

When people gather in New York City Sunday to remember the September 11th attacks, members of the clergy will have no official role. That was the decision by Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

NPR's Barbara Bradley Hagerty has a look at the reaction.

BARBARA BRADLEY HAGERTY: Each year for the past decade, the main ceremony has involved reading the names of victims, allowing moments of silence, but never opening the podium to clergy.

Julie Wood, a spokeswoman for the mayor, says it's the way family members want it.

Ms. JULIE WOOD (Spokeswoman, Mayor Michael Bloomberg): It's been widely supported in the past 10 years. And, you know, rather than have disagreements over which religious leaders participate, we wanted to keep the focus of the commemoration ceremony on the family members of those who died on 9/11.

Dr. RICHARD LAND (Southern Baptist Convention): As more and more people find out about this, they're incredulous.

HAGERTY: Richard Land of the Southern Baptist Convention says ground zero is a sacred place, and barring clergy from an official role is an insult.

Dr. LAND: It's clear that there are attempts by some to marginalize religious expression and religious faith.

listen now or download Morning Edition

Progressive Christians Join Controversy over Excluding Clergy at 9/11 Event

(CNN) - A handful of progressive Christian leaders are joining the mostly conservative chorus of religious leaders who are criticizing New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg for excluding clergy from this weekend’s 9/11 commemoration event at ground zero. But there’s a twist.

In addition to criticizing Bloomberg, progressive religious leaders are also taking aim at prominent conservatives who’ve blasted Bloomberg in recent days, alleging that those critics are stoking division at a time that calls for national unity. The group is planning a press conference near ground zero on Friday to stress that "religion should not be excluded from 9/11 remembrances" but to also "urge unity, not division, on 9/11," according to a Tuesday press release.

The Friday press conference, which will overlook ground zero, will feature Jim Wallis, who leads the evangelical social justice group Sojourners; the Rev. Floyd Flake, a prominent New York pastor and former Democratic congressman; and Geoff Tunnicliffe, who heads the World Evangelical Alliance.

"Mayor Bloomberg made an understandable but regrettable decision," said Tim King, communications director for Sojourners, an evangelical Christian social justice group that is helping to plan the press conference. "Religion, and religious leaders, have caused a lot of unnecessary conflict and controversy," King wrote in an e-mail message. "But avoiding religion entirely does not get to the root of the problem."

Libya Stresses Forgiveness, Reconciliation and Rebuilding

Muslim theologian runs stabilisation team

(Reuters) - When the officials guiding Libya's post-Gaddafi transition list their most urgent tasks, they talk about supplying water, paying salaries or exporting oil, and then add something quite different -- fostering reconciliation.

The focus on forgiveness might have seemed out of place at meetings in Paris on Thursday and Friday where world leaders and Libya's new administration discussed problems of democracy, investment and the unblocking of Libyan funds held abroad. But the example of Iraq, which plunged into chaos and bloody strife after the United States-led invasion in 2003, convinced the Libyans planning the transition from dictatorship and war that the country's needs were more than just material. "You cannot build a country if you don't have reconciliation and forgiveness," said Aref Ali Nayed, head of the stabilization team of the National Transitional Council (NTC).

"Reconciliation has been a consistent message from our president and prime minister on, down to our religious leaders and local councils," he told Reuters in an interview.

The stabilization team, about 70 Libyans led by Nayed from Dubai, was so versed in the mistakes following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein that they made sure they didn't repeat one of the more shocking -- the looting of Baghdad's main museum. "I'm happy to report that no museum was looted in Tripoli," said Nayed, stressing the country's cultural heritage had to be protected. "The banks were also safeguarded early on."

WRONG ROAD TO TAKE

In contrast to Iraq, where the U.S. decision to sack all members of Saddam's military and Baath party helped drive men into an armed insurgency, Tripoli will keep almost all Gaddafi-era officials in their posts to ensure continuity. "Destruction and disbandment is the wrong road to take," said Nayed. "It's better to take a conservative approach, even if it's not perfect, and build on it slowly."

The focus on reconciliation comes naturally to Nayed who, apart from being the head of an information technology company and the new NTC ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, is an Islamic theologian active in interfaith dialogues.

How Religion Can Inoculate Against Radicalism

The lesson of my retreat from a London university's Islamic Society

In the fall of 1989, I arrived as a student at the Royal London Hospital medical college, part of the University of London. I was one of only a handful of Muslim students in my year and, for us, the entire social scene felt alien. It all seemed based around dancing, alcohol and socializing with the opposite sex. We were left in a vacuum that the school's Islamic Society quickly offered to fill. Its members were comradely, welcoming and—crucially—had great food.

They knew we were lost and early on they started to explain how the alienation we felt was something we should cherish rather than try to overcome. The reason they gave was that we were better than the "kufar"—infidels—outside of our gathering. It was at this point that the tone of the Islamic Society's meetings started to change. Our duties to our religion started to merge with a series of geopolitical aims involving the establishment of a global Islamic state and the overthrow of the capitalist/Zionist system.

I soon dropped out of the Islamic Society and widened my social circle to include non-Muslims. But several of my friends had become intoxicated by the whole thing, even dropping out of the university because of it. At first I didn't give this much more thought—until 9/11, that is.

Then, as a practicing psychiatrist, I started to read articles about how radicalization occurs, especially around adolescence and through universities, where ideas like the need to create a global Islamic state—a new Caliphate—were being spoon-fed to vulnerable youngsters. This is what happened in Hamburg when the perpetrators of 9/11 were students there.

Why did I leave the Islamic Society while others stayed—and even, in some cases, wound up in Pakistan networking with fellow Islamists? What was the difference between us? The answer may be found somewhere in our earlier lives.

Those men who were the most opposed to the perverted messages being peddled by the Islamic Society were those who had been brought up by religious parents. One friend, who had been steeped in mainstream Islam as a child, used to tell me that the doctrine being preached at the Islamic Society was, in his view, so aberrant that it risked becoming toxic. He firmly believed that MI5 (British domestic intelligence) ought to be keeping an eye on these guys, and that was 10 years before 9/11. Those who had no exposure to Islam prior to the encounter with extremist recruiters seemed more likely to follow them.

After Sept. 11, 'Religion Can No Longer Be Ignored'

"Religion, at last, can no longer be ignored."

That was one of five "unintended, unforeseen" consequences of 9/11, according to historian R. Scott Appleby of University of Notre Dame.

Reporting on the spiritual impact of 9/11 has given me the chance to talk longer with Appleby and with theologian and psychologist Fraser Watts who raises the provocative idea that religion can be "healthy or unhealthy."

Both spoke this weekend at the Templeton-Cambridge seminars on Science and Religion sponsored by the Templeton Foundation (check tweets for more seminar insights at #TCJF).

Appleby, who co-chaired the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and Task Force on Religion and the Making of U.S. Foreign Policy, also directs "Contending Modernities," a program examining the interaction of Catholic, Muslim and secular forces in modern world.

His five points began with the tidal shift in views on religion in academia and politics. Following World War II the dominant view was that religion would inevitably give way to secularism, become privatized and be increasingly irrelevant in the public square. That "secular myopia" vanished "when 9/11 made it palpably clear that religion does matter in all these realms."

- Religion is now being treated with more depth and sophistication -- by media, government and academia. There's new recognition that believers are "not all pathological or irrational or crazy. We see more nuance now. And we see that people are making a conscious and reasoned choices to hold on to faith.

- "Islam has been put in the spotlight" with consequences to the good, such as the Common Word document by Muslim scholars addressed to the Catholic Church, and to the bad, such as the "new McCarthyism" of fear and anger toward Muslims. Appleby cites new initiatives around the world in serious interfaith, interreligious dialogue and collaboration.

- There's a new interest in examining the structural and substantive ways that "healthy" religion is working in the world for promoting peace and social justice and defeating poverty and disease. The world's challenges have to be met collectively and cannot be resolved with the faith communities.

9/11 Traced New Spiritual Lines

The terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, delivered an unfathomable religious jolt. Thousands were killed in a cruel, distorted vision of Islam, a religion that teaches peace. And for millions of Americans, the immediate response was to drop to their knees in prayer.

Sanctuaries filled for memorial services. Cardinal Edward Egan of New York remembers crowds overflowing St. Patrick's Cathedral.

A decade later, the soulful response seems fleeting. Statistically, the rush to the pews was a mere blip in a long-standing trend away from traditional religious practice, according to tracking studies by The Barna Group, a Christian research company. What's lingering is the spiritual impact revealed when 9/11 stories are recounted through individual recollections of faith reborn, revitalized or reshaped.

This is how people speak of an internal resetting of the compass, of journeys down pathways once unfamiliar, even unimagined. Pastor Mark Driscoll, who was 30 and just building his Seattle church a decade ago, says he discovered he was more fragile, more dependent on God, and more urgent about launching new churches than he'd known.

"Life is filled with opportunities to do good. We don't know how many we have, so you want to be there to invest, love and not take any day for granted," he says. His Mars Hill Church is now a multisite mega-church and he is a co-founder of Acts 29, a network that has launched 400 new congregations here and abroad.

Fatemeh Fakhraie, then a college freshman in Utah, was "just a white girl with a funny name" when the 9/11 attacks "found my identity for me before I was ready to find it for myself."

Within a few years, the U.S.-born daughter of Iranian parents began practicing Islam with fresh commitment. She founded and edits a website, Muslimah Media Watch, where 16 feminists of faith critique coverage of their issues in world culture. This month, as she says her prayers during Ramadan, Fakhraie, based in a Portland, Ore., suburb, observes, "Sept. 11 was 10 years ago and the media are still trying to explain Islam."

Others found themselves trying to explain Judaism and Christianity.

Insight: Arab Spring Raises Hopes of Rebirth for Mideast Science

CAMBRIDGE, England (Reuters) - Egyptian chemist Ahmed Zewail first proposed building a $2 billion science and technology institute in Cairo 12 years ago, just after he won a Nobel Prize. Then-President Hosni Mubarak promptly approved the plan and awarded Zewail the Order of the Nile, Egypt's highest honor. Within months, the cornerstone was laid in a southern Cairo suburb for a "science city" due to open in five years.

But while Zewail, who has taught at Caltech in California since 1976, went on to collect more awards and honorary doctorates abroad, his pet project got mired in a jungle of bureaucracy and corruption.

His growing popularity in Egypt, where he was touted as a possible presidential candidate after mass protests brought down Mubarak this year, seemed to threaten the officials overseeing the institute, so they blocked it every way they could. "We didn't get anywhere," Zewail told Reuters back in February.

But with revolution now sweeping the Middle East, Egypt's ruling military council and interim civilian government gave the project the green light in June. Supporters hail the decision as a positive step toward a new, more modern Middle East.

"Some people in the old regime were not happy with the limelight focused on Dr Zewail," said Mohammed Ahmed Ghoneim, a professor of urology at Egypt's University of Mansoura and a member of the board of trustees. But now, he noted with satisfaction, "the decision makers have changed."

The project is a "locomotive that will pull the train of scientific research in this country," he said.

The poor state of science in the Middle East, especially in Arab countries, has been widely documented. Only about 0.2 percent of gross domestic product in the region is spent on scientific research, compared to 1.2 percent worldwide. Hardly any Arab universities make it into lists of the world's 500 top universities.

But Arab scientists say the first steps toward change have been taken. A recent Thomson Reuters Global Research Report showed countries in the Arab Middle East, Turkey and Iran more than doubled their output of scientific research papers between the years 2000 and 2009. The progress admittedly started from a low base, rising from less than 2% of world scientific research output to more than 4% at the end of the decade, but the curve is definitely pointing upwards. "The region is taking a growing fraction of an expanding pool," the report said.

"The Arab-Muslim world has improved greatly, even if the universities are still pretty mediocre by and large," said Nidhal Guessoum, an Algerian astrophysicist who teaches at the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates. "The educational system in primary and secondary schools is still lagging behind world standards, but relative to what it was 30-50 years ago, there is clearly a huge improvement."

Call for Increased Dialogue between Journalists and Scientists

A panel consisting of high-profile international and local members of the media called for increased dialogue between journalists and the science community at the closing session of the Middle East’s first "Belief in Dialogue: Science, Culture and Modernity" conference, organized by the British Council in conjunction with American University of Sharjah (AUS) and held under the patronage of His Highness Sheikh Dr. Sultan Bin Mohammad Al Qassimi, Supreme Council Member, Ruler of Sharjah and Founder and President of AUS.

The closing media panel session chaired by Julia-Vitullo Martin, Co-Director of the Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Fellowships in Science and Religion, engaged participants in a lively debate about the opportunities available in covering science, culture, and modernity as well some of the barriers. Participants included Francis Matthew - Editor-At-Large of Gulf News; Nabil Khatib - Editor-in-Chief of Al-Arabiya News Channel; Mishaal Al-Gergawi, blogger and social commentator; Martin Redfern - BBC World Service; John Siniff-USA Today; Andrew Brown - The Guardian; Ehsan Masood- Editor, Research Fortnight; Dr. Qanta Ahmed- Author, Associate Professor, State University of New York and Contributor to the Huffington Post; and Abeer Al-Najjar-Assistant Professor, American University of Sharjah.

The panel session, which was open to the public, was attended by members of the local media and university students. The need for more diversity in the region’s media including the recruitment of reporters dedicated to covering science, culture and religion was at the forefront of the discussion. The panel criticized the region’s lack of specialized journalists, saying more needed to be done to tackle complex and often sensitive issues of science, religion and culture. Members of the audience suggested that local editors commit to appointing niche reporters who could simplify complex issues and generate reader interest in subjects which are challenging and sometimes controversial.

Fern Elsdon-Baker, Director of the British Council’s Belief in Dialogue program, commented on the closing panel session, "It's clear from this discussion that our cultural understanding of science is highly dependent on how the media communicates it. Greater resources and training must be committed by the media and researchers in this field, as global links and better dialogue will partly depend on our appreciation of scientific development and the possible changes that can come from it."

On the sidelines of the closing session, Nidhal Guessoum, Professor of Physics, AUS, urged the local media to report on developments in the field of science, saying, "We are seeing fewer students interested in pursuing careers in science and research as those types of jobs are typically perceived as not glamorous or financially lucrative enough. The majority of students I speak to cannot name even one Arab scientist yet they can confidently list a number of Arab entertainers, entrepreneurs and athletes."

The World Debate: Islam v Science

Belief and Modernity--Science and Culture in Islam

Political change is sweeping through the Islamic world, with many countries questioning their traditions and looking for a new style of democracy. But just what is the relationship between science and belief in the region? A thousand years ago the Middle East was the main repository for ancient scientific knowledge, which was not only preserved but nurtured and developed, laying the foundations of fields such as mathematics, astronomy and medicine as well as philosophy. But today, not one of the world's top 400 universities is in a Muslim country. So what went wrong and can it now begin to change? Can a culture of religious belief foster the questioning approach essential for scientific breakthroughs and the building of a science-based economy?

Writer and science editor Ehsan Masood chairs a discussion before an audience at the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates. On his panel are Nidhal Guessoum, Professor of physics and astronomy at the American University of Sharjah; Rana Dajani, assistant professor of molecular biology at the Hashemite University, Amman, Jordan; writer and physicist Paul Davies who directs Beyond, the Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science at Arizona State University; and Qanta Ahmed, medical doctor and writer based in New York who has worked as a physician in Saudi Arabia. Also contributing are distinguished guests and students from the audience.

The conference Belief in Dialogue: Science, Culture and Modernity was jointly organised by the British Council, in partnership with the American University of Sharjah and in association with the International Society for Science and Religion (ISSR). The conference forms part of the British Council's global Belief in Dialogue program

Producer: Martin Redfern

listen now or download Last broadcast on Sunday, 14:05 on BBC World Service.

Just What is an Islamic Reformer?

Irshad Manji has rankled Muslims since The Trouble with Islam. Published in 2004, early in the post-9/11 era, her book was a sexy shtick: Islam needs reform, not Muslims. Manji was quickly accorded, and later claimed, the laurels of "Muslim Reformer," though close scrutiny fails to reveal any trace of such "reforms." Allah, Liberty & Love only confirms this view.

Manji can don the mantle of reformer precisely because Muslims are beset by faith illiteracy, enabling the spread of frankly un-Islamic values. Meanwhile, non-Muslims remain perpetually naive about authentic Islamic philosophy as they look toward unschooled, faith-illiterate diaspora Muslims for interpretations of Islam. This bilateral ignorance works very much to the advantage of both contemporary radical Islamists and savage Islamophobes.

Manji’s poised banter, however, can do as much damage as the ravings of a bearded fanatic, even while they speak to completely opposite values. That’s because she inexplicably lambastes "moderate" Muslims, condemning them just as vehemently as a neo-orthodox cleric (a Diaspora Muslim who hides between ritualistic Islam for purposes of political identity) might do.

The liberal Muslim reformer and neo-orthodox cleric share one critical, empowering thing: a malleable audience. Without context, or engagement with either Islam or the Muslim world in their highly complex, furious heterogeneity, it’s just as easy to influence the insular naivety of a Western audience as it is to influence blank-slated minds bobbing back and forth in a madrassa, be it in Manchester or Mecca. Manji succeeds precisely because of such naiveté.

Allah, Liberty & Love is disheartening. Its scholarship is cut-and-paste. Throughout, Manji leans heavily on e-mail and Facebook correspondence with her followers, reproducing dozens of such interchanges (self-congratulatory ripostes intact) to stultifying effect. A cacophony of repetitive electronic dialogues (reproduced verbatim in the vernacular SMS text that increasingly passes for English) reveal an animated but uninformed following of Muslims who seek answers from Manji, yet lack access to serious scholars. This is little more satisfying than stumbling over a Facebook forum.

Mideast Christians Struggle to Hope in Arab Spring

(Reuters) - Middle East Christians are struggling to keep hope alive with Arab Spring democracy movements promising more political freedom but threatening religious strife that could decimate their dwindling ranks. Scenes of Egyptian Muslims and Christians protesting side by side in Cairo's Tahrir Square five months ago marked the high point of the euphoric phase when a new era seemed possible for religious minorities chafing under Islamic majority rule.

Since then, violent attacks on churches by Salafists -- a radical Islamist movement once held in check by the region's now weakened or toppled authoritarian regimes -- have convinced Christians their lot has not really improved and could get worse. "If things don't change for the better, we'll return to what was before, maybe even worse," Coptic Catholic Patriarch of Alexandria Antonios Naguib said at a conference this week in Venice on the Arab Spring and Christian-Muslim relations. "But we hope that will not come about," he told Reuters.

The Chaldean bishop of Aleppo, Antoine Audo, feared the three-month uprising against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad spelled a bleak future for the 850,000 Christians there. "If there is a change of regime," he said, "it's the end of Christianity in Syria. I saw what happened in Iraq."

The uncomfortable reality for the Middle East's Christians, whose communities date back to the first centuries of the faith, is that the authoritarian regimes challenged by the Arab Spring often protected them against any Muslim hostility.

DEPENDENT ON DICTATORS

Apart from Lebanon, where they make up about one-third of the population and wield political power, Christians are a small and vulnerable minority in Arab countries. The next largest group, in Egypt, comprises about 10 percent of the population while Christians in other countries are less than 5 percent of the overall total.

Under Saddam Hussein, about 1.5 million Christians lived safely in Iraq. Since the U.S.-led invasion in 2003, so many have fled from Islamist militant attacks that their ranks have shrunk to half that size, out of a population of 30 million. Arab dictators led secular regimes not to help minorities but to defend themselves against potential Islamist rivals. Christians had no choice but to depend on their favour.

Does Islam Stand Against Science?

We may think the charged relationship between science and religion is mainly a problem for Christian fundamentalists, but modern science is also under fire in the Muslim world. Islamic creationist movements are gaining momentum, and growing numbers of Muslims now look to the Quran itself for revelations about science.

Science in Muslim societies already lags far behind the scientific achievements of the West, but what adds a fair amount of contemporary angst is that Islamic civilization was once the unrivaled center of science and philosophy. What's more, Islam's "golden age" flourished while Europe was mired in the Dark Ages. This history raises a troubling question: What caused the decline of science in the Muslim world?

Now, a small but emerging group of scholars is taking a new look at the relationship between Islam and science. Many have personal roots in Muslim or Arab cultures. While some are observant Muslims and others are nonbelievers, they share a commitment to speak out—in books, blogs, and public lectures—in defense of science. If they have a common message, it's the conviction that there's no inherent conflict between Islam and science.

Last month, nearly a dozen scholars gathered at a symposium on Islam and science at the University of Cambridge, sponsored by the Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Programme in Science & Religion. They discussed a wide range of topics: the science-religion dialogue in the Muslim world, the golden age of Islam, comparisons between Islamic and Christian theology, and current threats to science. The Muslim scholars there also spoke of a personal responsibility to foster a culture of science.

One was Rana Dajani, a molecular biologist at Hashemite University, in Jordan. She received her undergraduate and master's degrees in Jordan, then took time off to raise four children before going to the University of Iowa on a Fulbright grant to earn her Ph.D. Now back in Jordan, she is an outspoken advocate of evolution and modern science. She has also set up a network for mentoring women, and she recently started a read-aloud program for young children at mosques around Jordan.

As if that weren't enough, Dajani helped organize a committee to study the ethics of stem-cell research, bringing together Jordanian scientists, physicians, and Islamic scholars. (The traditional Muslim belief is that the spirit does not enter the body until 40 days after conception, which means many human embryonic stem cells can be harvested for research.) "Being a Muslim, living in a Muslim world, Islam plays a big role in our everyday lives," she says. "We need to understand the relationship between Islam and science in order to live in harmony without any contradictions."

For these scholars, the relationship between science and Islam is not a dry, academic subject. Many of the hottest topics in science—from the origins of the universe and the evolution of humans to the mind/brain problem—challenge traditional Muslims beliefs about the world.

"Remember, these are human issues," says Nidhal Guessoum, an Algerian-born astrophysicist at the American University of Sharjah, in the United Arab Emirates, who was also at the Cambridge symposium. "It's not an experiment in the lab. I'm talking about my students, my family members, the media discourse that I hear every day on TV, the sermons I hear in the mosque every Friday."

With his blend of charisma and keen sense of how to navigate the tricky terrain between modern science and Muslim faith, Guessoum is emerging as one of the key figures in public debates about Islam and science. He has a new book, Islam's Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science (I.B. Tauris), and this month his university will host an international conference called "Belief in Dialogue: Science, Culture and Modernity."

Social Cohesion Needs Religious Boundaries

The new Prevent strategy shows an old pattern of social organisation is emerging in a new form, around new doctrines.

This is often said to be a country that has outgrown established religion. Yet the two big academic stories of the day show that the problems of social coherence persist that the Church of England was established to solve; and the secularists have no newer or better ideas how to deal with them.

Look at the Prevent agenda first. The government's position here is that certain religious or theological beliefs are incompatible with the values on which this country depends; and this is true even if they are compatible with the law. No one suggests that Hizb ut-Tahrir is currently illegal. Few people suggest it should actually be banned. But its beliefs are subversive of the common decencies of society. Islamists, the government now argues, should not be given positions of authority nor government money. This is pretty much the position that Catholics were in 400 years ago: in fact James I's speech after the gunpowder plot was discovered is eerily reminiscent of the Bush/Blair rhetoric after 9/11: "Though religion had engaged the conspirators in so criminal an attempt, yet ought we not to involve all the Roman Catholics in the same guilt, or suppose them equally disposed to commit such enormous barbarities."

Or, as we would now say, he condemned extremist Catholics, but was careful to distinguish them from moderates. Considering that the gunpowder plot was an attempt at hugely destructive suicide terrorism, this was a remarkably magnanimous position. But it does show the way in which the established churches of England and Scotland were political and moral constructions necessary for these nations to emerge and function. Laws are simply not enough. Nations need common values and perhaps more than that, common symbols of the sacred. The whole point about a symbol is that it is irrational: people are loyal to it without calculation, and this unreasoned quality is exactly what makes them trustworthy.

What's more, symbols, unlike values, can be unequivocally rejected, providing a marker of who is in and who out. Everyone is in favour of motherhood, which is a value, but to venerate the mother of Jesus, who is a symbol, is a profoundly divisive act, and has sometimes come close to treason. It was certainly enough to exclude you from university in England for nearly 300 years.

EU Assures It Backs Religious Freedom in Mideast

Reuters) - European Union leaders assured senior religious figures on Monday they would defend the freedom of belief in the Middle East as part of their support for the spread of democracy in the Arab world. European Commission President Jose Barroso told 20 Christian, Muslim, Jewish and Buddhist leaders at an annual consultation in Brussels that the EU aimed to promote democracy and human rights.

Several of the Christian representatives present expressed concern about religious freedom in the mostly Muslim Arab world, which has seen more freedom of speech in recent months but also more violent attacks on Christian minorities in some countries.

Barroso said the changes in the Arab world were "of historic proportions" and compared the challenge of anchoring democracy there to the task the EU found in post-communist Europe. "I strongly believe these challenges cannot be met without the active contribution of the religious communities," Barroso told the meeting. Democratic rights included freedom of religion and belief, he stressed.

European Council President Herman Van Rompuy said "there is no contradiction between Islam and democracy. This period of openness must be maintained after the revolutions and religious and other minorities must be respected."

CHRISTIAN CONCERNS

Rotterdam Bishop Adrianus van Luyn, head of the COMECE commission of Roman Catholic bishops conferences in the EU, said the progress and stability the EU sought in the Arab world would depend on an improved relationship between religions there. "This requires freedom for all faiths, an end to the discrimination of smaller religious communities and the participation of moderate forces in the construction of society," he said.

In recent months, Arab Christians and Muslims have both prayed together and clashed, he said. "Religious differences have often been manipulated or even whipped up on purpose," he said. "The role of the different regimes in this is unclear."

Harun Yahya's Muslim Creationists Tour France Denouncing Darwin

France’s staunchly secularist educational establishment was shocked four years ago when schools around the country suddenly began receiving free copies of a richly illustrated Muslim creationist book entitled the "Atlas of Creation." The book by Istanbul preacher and publisher Harun Yahya had come out in Turkey the year earlier. After the French Education Ministry warned teachers not to use it and held a seminar on how to deal with creationist pupils, the issue dropped out of the public discussion. But the Harun Yahya group has been spreading its view in France and is now holding a series of conferences on them. Here is my feature after visiting one of the first meetings in the current series:

Muslim creationists tour France denouncing Darwin

AUBERVILLIERS, France (Reuters) – Four years after they first frightened France, Muslim creationists are back touring the country preaching against evolution and claiming the Koran predicted many modern scientific discoveries. Followers of Harun Yahya, a well-financed Turkish publisher of popular Islamic books, held four conferences at Muslim centers in the Paris area at the weekend with more scheduled in six other cities.

At a Muslim junior high school in this north Paris suburb, about 100 pupils — boys seated on the right, girls on the left — listened as two Turks from Harun Yahya’s headquarters in Istanbul denounced evolution as a theory Muslims should shun. "We didn’t descend from the apes," lecturer Ali Sadun told the giggling youngsters. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, he said, was "the scientific basis to defend atheism."

How Will the Arab Spring Affect Religion and Science?

In last week’s news, no doubt the biggest Islam-related story spun off the killing of Osama bin Laden, and how it would affect Islamic radicals for whom he was a leader. But a sadder conversation with broader implications was taking place over candlelight in an elegant dining room one evening in Cambridge, England.

It was the concluding event of a weeklong seminar for religion and science journalists who had come to England to hear from Muslim scientists about the most pressing science issues across their enormous, diverse faith communities. And it was grim.

There was the soft-spoken Jordanian molecular biologist and professor who said over dinner Saturday night that the lack of freedoms in many parts of the Muslim world had resulted in students unfamiliar with basic critical thinking needed to produce real science. Students in her classes don’t question, she said. The Pakistani-British sleep specialist who worked for years in Saudi Arabia and said a culture without freedom of thought had left scientists in many parts of the Muslim world in "an intellectual vacuum."

To whatever degree the handful of speakers at the seminar – which also included an Algerian astrophysicist and a French cosmologist, among others – represent at least a chunk of thought among Muslim scientists working outside the West, the future feels uncertain.

Part of the issue is one of language. There’s obviously no such thing as "the Muslim world," or "Islamic science." But there is certainly a lot of discussion about how recent revolutions across North Africa and the Middle East might affect the advance of science, which was for centuries the pride of the Muslim world.

Rana Dajani, who launched a program to open dozens of public reading spaces for youth in Jordan because she said the country lacks a culture of reading for pleasure, said she is hopeful that loosening of government control will automatically lead to a improved climate for scientists. Less corruption, cronyism, the building of a meritocracy.

And how a rise in science could affect practice and understanding of Islam?

Osama's Islam-Violence Link Weighs Heavy on Muslims

PARIS (Reuters) - Osama bin Laden's radical Islamism has had a devastating impact on Muslims around the world by linking their faith with violence and using religious texts to justify mass killings.

His "jihadist" strategy has claimed the lives of many thousands of Muslims in Iraq, Pakistan and Afghanistan, as well as in the United States, Europe and Africa.

It has also tarred Muslims with suspicion and helped feed prejudice against them. Especially in the West, many Muslims felt pressured to denounce a man they never identified with.

"The link he made between violence and Islam made people think this was a religion of terrorists," said Dalil Boubakeur, rector of the Grand Mosque of Paris.

"In Western countries, we've had to show on a daily basis that Islam is not violent and Osama bin Laden does not represent Muslims," he said. France is home to Europe's largest Muslim minority of about five million people.

Muslim leaders have issued many denunciations of the radical Islamist violence championed by bin Laden. Mainstream scholars have drawn up declarations and fatwas to counter his arguments with opposing views from the Koran. While these may have influenced some undecided Muslims, they had little apparent success in shaking a view that bin Laden represented an important current within Islam.

ARAB REVOLTS HELP CHANGE IMAGE

The recent wave of pro-democracy uprisings in the Arab world has gone some way to weakening the perceived link between Islam and violence. The world's media have shown pictures of young Muslims campaigning for civil rights without resorting to religious violence.

"In public and private discussion on the main issues facing the Muslim world, violence through radical religious means used to be quite prominent," said H.A. Hellyer, a fellow at Warwick University in Britain. "That has disappeared in recent months."

Tunisia, Libya, and Freedom

Tunisian willingness to house fleeing Libyans reminds us that caring for others is really a human, not a technical, act.

Many tens of thousands of refugees have now fled Libya and crossed to the relative safety of Tunisia. Their stories will, no doubt, be ones of terror and horror. And yet, there are tales of deep humanity too in their flight. A UNHCR spokesperson, Andrej Mahecic, has reported that fewer than one in ten of the Libyan arrivals are staying in refugee camps. Instead, the vast majority of those fleeing have been welcomed by Tunisian communities. The homeless Libyans are being hosted by locals, at the locals' expense and with great generosity, given the Tunisians' own resources are not great.

It's a moving tale, especially given the worries rattling around rich Europe about the migration implications of the Arab uprisings, given our own habits of locking up immigrants behind bars. Of course, the situation in Libya is an emergency. And there are deep bonds between these peoples, founded upon a common religion. But the story prompts thoughts about the nature of altruism and what happens when caring for others comes to be seen as primarily a technical, rather than a human, problem.

There is a lot of discussion about altruism today, driven in large part by the trouble it causes evolutionary theory. In the dog-eat-dog world of crude Darwinism, why should it be that some species collaborate, even to the point of self-sacrifice? In fact, Martin Nowak, author of SuperCooperators, argues that co-operation is quite as central to evolution as competition. You only need do the maths, he explains, the cost-benefit analysis. Working together in groups works. Only, that's not the whole story, he continues.

The problem with a cost-benefit analysis approach is that it reduces altruism. Instead of being about selflessness, it becomes a new form of selfishness. I'll scratch your back if you scratch mine. Maybe not today. Maybe not tomorrow. But I'll remember what I did for you, and hold you forever in my debt.

Transfer that into the moral discourse that shapes a culture, and you find yourself with a world in which virtues such as trust, courage, loyalty and sympathy struggle to thrive. Instead of honour, we write contracts. Instead of bonds of friendship, we work out our relationship to one another in the courts.

Nowak recognises that the maths can provide only half the story, and it misses out the most important part too, namely the role played by intention. What are the values that underpin co-operation? What are the beliefs that allow it to flourish? This is the vital discussion, he asserts, and one that must include politicians and philosophers, artists and theologians, alongside the scientists.

In Our Silence, Muslim Americans Essentially Collaborate with the Islamists

Claims of 'McCarthyism' in the wake of the Peter King hearings threaten to suffocate a vital discourse on Islamism just when we need it most. Even as cries of 'Islamophobia' seek to smother debate, Muslim Americans must speak up, and out loud.

Decapitation has a way of clearing one’s head. My invitation to a beheading came from former Israeli officer and counter-terrorism expert Richard Horowitz, who thought that if I watched a video of one in the security of his library, I would understand what he already knew: just how ferociously we in the West are hated. In the video, a Muslim boy beheads a man. The murderer is 10.

I am a woman who practices medicine and Islam. Islam took me to Mecca and Hajj. Medicine took me to Riyadh and London. Each capital hosts communities espousing Islamist neo-orthodoxy. Both spawn violent jihadist ideologies. Listening to counter-terrorism experts and examining the ugly underbelly of contemporary radical Islamism has taught me what Muslims in Mecca, Riyadh, or London could not: the difference between Islam and Islamism.

Rep. Peter King (R) of New York’s Senate hearings seek answers to these and other questions, while attacks of "Islamophobia" and "McCarthyism" threaten to suffocate this vital discourse. As a Muslim, watching Islamists at work lends me rare perspective. Mr. King’s hearings offer the public this same perspective, just when it is needed most.

Suicide bombers should be called homicide bombers

Islamist terrorism places martyrdom at its center, distorting Islam into a false faith valuing death above life. Islam reviles suicide, yet suicide operations are now synonymous with Islamist terror. This is deliberate.

Suicide distracts. Suicide enthralls. Our terror terminology appears transfixed by these suicide bombers’ singular pursuit of self-destruction, seemingly overlooking the murder these martyrdom operatives commit. Dr. Joan Kirschenbaum Cohn, assistant professor of Medicine and Community Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center, observes these martyrs are better termed homicide bombers. Somehow this phrase never caught on.

These "martyrs" seek only to divide: the living from the dead; those who believe in death from those who believe in life; those who choose nihilism over those who guard pluralism. Islamist elements, not Senate hearings, have created the same divides here in America. These divides are not the work of Americans marginalizing Muslims. These divides are the work of Muslims marginalizing Muslims. We have polarized ourselves.

Shame is uncomfortable

The duplicity of the Islamist operative horrifies most. A fellow passenger on a plane, a major within our ranks, a mediocre MBA at the office, always a fellow "Muslim," the Islamist moves among us. But for Muslims, our discomfort descends deeper. Islamist operatives claim to be the unequivocal, ultimate Muslim, shaming those who refuse to join their cause as not "real Muslims." Such shame is uncomfortable, since being a good Muslim means being part of a global brotherhood. If we separate, we reveal the fissures among us. Instead, sheltering ourselves from this distress, we falter and choose denial.

Asking 'Islam's Quantum Question'

Can science and Islam be reconciled? A conversation with Nidhal Guessoum.

Revolution is in the air throughout the Arab Muslim world. For some Muslims, hope for political change entails hope for cultural change. And for Algeria-born astrophysicist Nidhal Guessoum, a professor of physics at the American University of Sharjah, the "Arab 1848," as some have called it, opens up the possibility that the Arab Muslim world can join the global scientific mainstream. His new book, Islam’s Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science, explores the history of scientific thought in Islam, examines where Muslim intellectual culture went wrong, and offers a constructive way forward for science and religion among 1.6 billion of the world’s people. Guessoum recently spoke to BQO.

The United Nations has issued several Arab Human Development Reports over the past decade. They point out how much the Arab world lags in democracy, civil liberties, education, and economic progress. The UN documents are particularly hard on Arab societies for their "stagnation" in scientific research, pointing out, for example, that the number of scientists and engineers working in research and development in Arab countries is roughly one-third of the global average. Do you think that the recent and ongoing revolutions across the Arab world will be good for science?

All sectors of activity in the Arab society have suffered during these decades of autocratic rule, from politics and economics to culture, science, and human rights. In my view, that stagnation and continuous falling behind was due to three factors: dictatorship (denial of basic freedoms), corruption (financial and moral), and nepotism and cronyism.

The mediocrity of the Arab world’s performance in academic and scientific fields is well documented in various reports, some of which you have mentioned. To give just a few examples: out of 1,000 or so universities in the Arab world, only two or three are in world’s top 500 — and they are ranked between 400 and 500; while the Arab world’s population makes up about five percent of the world’s and its financial resources are much larger than that, only 1.1 percent of the world’s scientific production comes out of the Arab region; the number of frequently cited scientific papers is 43 per million people in the USA, 80 in Switzerland, and 38 in Israel; it is 0.02 in Egypt, 0.07 in Saudi Arabia, 0.01 in Algeria, and 0.53 in Kuwait.

One of the reasons for the mediocre state of research in the region is the very low budget allocated for science: the fraction of the GDP spent on scientific research is 0.2 percent on average in the Arab world (0.05 percent in Saudi Arabia), compared to a world average of 1.2 percent.

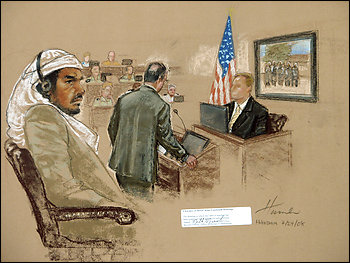

A Hearing To Ask: Are Muslims Being Radicalized?

SSome call the hearing a witch hunt. Others say it's a reality check.

House Homeland Security Committee Chairman Rep. Peter King, a Long Island Republican, believes the hearing he has scheduled for Thursday morning is a valuable investigation into the "radicalization" of many U.S. Muslims. The hearing, entitled "The Extent of Radicalization in the American Muslim Community and that Community's Response," will help lawmakers better understand the threats posed by radicals who live in the United States — and are tolerated by their fellow Muslims, he says.

"We are under siege by Muslim terrorists, and yet there are Muslim leaders in this country who do not cooperate with law enforcement," King told Fox News. "We have the reality that al-Qaida is trying to recruit Muslim Americans, and yet we have people in the Muslim community who refuse to face up to this." King says it's necessary to investigate homegrown terrorism.

But Corey Saylor, at the Council on American Islamic Relations, says that might be a valid topic — except that he believes King has an agenda.

Stacking The Deck Against Muslims?

"He's said things like, 'There are too many mosques in America.' He's alleged that 80 percent of American Muslim leadership is extremist, yet never produced a single bit of evidence to back that up," Saylor says. "So that's the kind of thing that leads you to the Salem witch trials, the Inquisition, and frankly, McCarthyistic hearings." Saylor fears King is stacking the deck against Muslims by calling witnesses who do not represent most Muslims in this country. He points to the primary witness, M. Zudhi Jasser, a doctor in Phoenix who founded what Saylor says is an obscure group called American Islamic Forum for Democracy.

For his part, Jasser says, it's clear that many Muslims have been radicalized: There have been 60 terrorism plots in the past two years. "Just look at the arrests — from Portland to Baltimore to the Times Square bomber, and on and on, there have been more and more arrests," he says. "So this is not just a pie-in-the-sky discussion. This is a reality that we have to deal with."

Jasser, who says his group has about 2,000 members, says America needs to understand the root cause of this violence. He describes this root cause as a "political movement of Islamism that has as a goal to create Islamic states, that want to put into place Shariah law, that give women third-class status, that give other faiths secondary status, that give moderate Muslims or critics of imams no voice."

listen now or download Listen to the Story: All Things Considered

Twitter and Other Services Create Cracks in Gadhafi's Media Fortress

The popular uprising in Libya is two struggles in one. First is the flesh-and-blood battle fought at horrific cost on the streets of Tripoli and throughout the North African nation.

The second, just as grim and no less dramatic, is the battle between Libyans and the government of Moammar Gadhafi over access to media and information.

For almost 42 years, Gadhafi has proved a genius in "erecting a seemingly impenetrable fortress, a very complex architecture to assure complete loyalty and unanimity in all messages having to do with Libya," according to Adel Iskandar of the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University.

The assault on that fortress has been joined by the "Libyan diaspora" - expats as well as family and friends of those struggling back home. In little more than a week, the international Libyan community has pulled together into a focused, urgent media world unto itself. The diaspora workers funnel text messages, photographs, and e-mail between Libya and the outside world, to support and guide the struggle back home.

Dina Duella, a freelance media professional in Irvine, Calif., is part of that sudden, vast network, relaying political and family news via Twitter, Facebook, and the good ol' telephone. And she's tired. "I haven't slept since last week," she said Thursday by phone, "and I know lots of others in the same situation. It's tense, conflicting, chaotic."

"It's an incredibly vibrant, indispensable community," said Iskandar, "literally blossoming all of a sudden, overcoming a very steep learning curve, and becoming radicalized, all in one week. It became a cyberactivist community with remarkable speed." Libya is not much like its neighbor to the east, Egypt.

"You can't use the Egypt model in Libya," said Duella, "because it would never work." Only six million people live in Libya, compared with Egypt's 80 million-plus. Egypt's Hosni Mubarak may have been an autocrat, but he seems mild next to Gadhafi and his iron choke hold since 1969 on society, the economy, and information. Gadhafi has always banned the sale of foreign newspapers. There is next to no tourism and no privately held TV or radio.

"Compared to other parts of the Arab world," Iskandar said, "there is less use of Internet, less use of Twitter and Facebook, partly out of fear, partly because there just isn't the access." He estimated there were 320,000 regular Internet users there, scant next to the 16 million in Egypt.

Libyan Islamic Scholars Issue Fatwa for Muslims to Rebel

A coalition of Libyan Islamic leaders has issued a fatwa telling all Muslims it is their duty to rebel against the Libyan leadership. The group also demanded the release of fellow Islamic scholar Sadiq al-Ghriani, who was arrested after criticising the government, and "all imprisoned demonstrators, including many of our young students."

Calling itself the Network of Free Ulema of Libya, the group of over 50 Muslim scholars said the government and its supporters "have demonstrated total arrogant impunity and continued, and even intensified, their bloody crimes against humanity."

Open dissent by established Muslim clerics is rare in North Africa, but the crackdown on protesters rallied the scholars to form the previously unknown Network of Free Ulema. Their first statement issued on Saturday denounced the government for firing on demonstrators who were demanding "their divinely endowned and internationally recognised human rights" and stressed the killing of innocent people was "forbidden by our Creator."

France Plans Nation-Wide Islam and Secularism Debate

France’s governing party plans to launch a national debate on the role of Islam and respect for French secularism among Muslims here, two issues emerging as major themes for the presidential election due next year. Jean-François Copé, secretary general of President Nicolas Sarkozy’s UMP party, said the debate would examine issues such as the financing and building of mosques, the contents of Friday sermons and the education of the imams delivering them.

The announcement, coming after a meeting of UMP legislators with Sarkozy on Wednesday, follows the president’s declaration last week that multiculturalism had failed in France. German Chancellor Angela Merkel and British Prime Minister David Cameron have made similar statements in recent months that were also seen as aimed at Muslim minorities there. France’s five-million strong Muslim minority is Europe’s largest.

Copé said the debate, due to start in early April, would ask "how to organise religious practice so that it is compatible in our country with the rules of our secular republic."

UMP parliamentarians said Sarkozy told them they had to lead this debate to ensure it stays under control. The far-right National Front, reinvigorated with its new leader Marine Le Pen, has recently begun a campaign criticising Muslims here.

"Our party, and then parliament, must take on this subject," they quoted Sarkozy as saying. "I don’t want prayers in the streets, or calls to prayer. We had a debate on the burqa and that was a good thing. We need to agree in principle about the place of religion in 2011."

France has sought to keep religion out of the public sphere since it officially separated the Catholic Church and the state in 1905. The growth of a Muslim minority in recent decades has posed new challenges that lead to sometimes heated debates. The government banned headscarves in state schools in 2004 and outlawed full face veils in public last year. But there are no rules about halal meals in schools, for example, or whether Muslims can pray in the streets outside an overcrowded mosque.

In Egypt's Secret Military Lies a Cautionary Tale

By kicking aside its president, dissolving its parliament and suspending its constitution, Egypt has wiped clean the slate of its government.

Maybe. There is a different slate in this potentially pivotal Arab nation — written largely in invisible chalk. Experts know just enough to read in it a cautionary tale. The military authorities who have taken control of Egypt have operated largely in secret to build their own empire of money and power.

"You have this huge beast of a thing in all sectors of Egypt's economic activity," said Robert Springborg, a Minnesota native whose extensive experience in the Middle East includes working as director of the American Research Center in Egypt. Currently he is a professor in the Department of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif.

And Egypt is taking a long-shot gamble by trusting that commanders of such immense power and wealth eventually will relinquish meaningful control to civilians, say Springborg and other experts. Even the Egyptian people do not know the full extent of the economic and political force their military leaders have amassed. No one does outside elite circles in Egypt because that force has been assembled over decades behind the veils of political expediency and national security.

Origins of a secret empire

The origins of this secret military economy go back before Egypt's now-deposed President Hosni Mubarak began his authoritarian rule some 30 years ago.

After World War II, Egypt asserted itself in the global expansion of military-industrial enterprise. It became the leading Arab manufacturer of aircraft and weapons. It set up a series of state-owned enterprises under the control of an Armament Authority commanded by a major general, according to Global Security.org. Its customers included the United States, European nations and neighboring Arab states.

Because Egypt considered the value of its military exports confidential, it omitted this information from its published trade statistics. It outlawed news coverage of the military enterprises. And it defied efforts by global financial institutions like the World Bank to lift the curtain of secrecy and bring the military-run factories into the private sector where they would be more visible and accountable. You have to go back to the 1980s to find estimates on the exports from this hidden industry. And those estimates range from $70 million a year in 1980s dollars to $1 billion.

Concern about Islamists Masks Wide Differences Among Them

PARIS, Feb 4 (Reuters) - Politicians and pundits wondering if Islamists will soon take power in Egypt or Tunisia might usefully ask first what the term "Islamist" means and what the Muslim leaders it describes say they want to do.

"Islamist" denotes an ideology that uses Islam to promote political goals. But it is so broad a term that it can apply both to Shi'ite Iran's anti-Western theocracy and to pro-business Sunnis trying to get Turkey into the European Union.

While the politically charged word can evoke violent action, such as that of Osama bin Laden's al Qaeda, many Islamists say they abhor the use of force and want to work within the law.

"We have to distinguish between different combinations of Islam and politics," said Mustafa Akyol, a columnist in Istanbul for Hurriyet Daily News. "A party can take its values and inspiration from Islam but still accept a secular state."

Noah Feldman, a Harvard University expert on Islamic law, said taking part in democratic politics can change Islamist parties, citing the AK Party in Turkey that came to power in 2002 after scrapping its ideal of creating an Islamic state.

"Once in power, you can no longer rely on slogans or ideology for votes, you actually have to deliver things," he said. "They've done an extraordinary job of that."

Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood and the Islamist Ennahda ("Renaissance") party in Tunisia have so far not been able to operate in open political systems, so their professed commitment to democracy has not yet been tested in daily practice.

Their programmes reflect a more moderate approach, however, than those of Lebanon's Hezbollah, the Palestinian Hamas or Iran.

Factbox: Egyptians Want More Islam in Politics