Society & Beliefs

Why We're All Fundamentalist

When did faith stop being about trust, and become a set of propositions to be believed? Mark Vernon looks back in history for clues to the fundamentals that fire a true life passion for people.

There is a story about Socrates, in which the sage of Athens is looking back on his life1. He recalls one day sitting with Plato, in the days of his great disciple's youth. Plato is talking. Socrates is watching him. He can see the freckles on Plato's face, his intelligent eyes, his seriousness, his confidence. Suddenly, Socrates is struck by a thought: 'I knew that if an archer were to shoot at him, I would step in front of him without hesitating and I'd take the arrow in my chest.' He knew this without a doubt. And then came a feeling that surprised him. 'I was smiling because I was truly happy.'

Human beings are all, in a sense, fundamentalists. Or at least, we might all hope to be so - an individual who knows who they would die for; what they would die for. It will be a person or belief so essential, so sacred, that sacrificing for it would not so much end your life as show your life has an end, in the sense of a goal, a reason, a meaning.

Further, knowing what you would die for means that you know what you live for. There is nothing that makes life more worth living; it generates purpose, commitment, love. It is liberating too. If you know you could let go of life, you can live more freely now. Socrates smiled. He was happy. Fundamentalism, though, is different. In its rarer, violent forms it is a basic conviction about life too, though gone wrong. Love reveals what you would die for. But the passions of hatred and war can do so too, as the jihadis learnt in the Afghan conflicts of the last decades of the 20th century. Further, this kind of fundamentalism is not so much about what you would die for as what you would kill for.

Is the Death Penalty in Keeping with Catholic Doctrine?

September has been execution season in the United States. In the past month, Texas executed two prisoners, Florida and Alabama each sent an inmate to the death chamber, and in Georgia, the controversial lethal injection of Troy Davis went forward despite last-minute consideration of his case by the U.S. Supreme Court. The justices did halt the scheduled executions of two other Texas inmates, and Republican Governor John Kasich commuted the death sentence of an Ohio prisoner.

The issue has even reentered the realm of presidential politics, after all but disappearing for several decades. In his first debate with fellow GOP contenders, Texas Rick Perry fielded a question about the record number of executions over which he has presided as governor (234 at the time of the debate, 236 now). "Have you struggled to sleep at night with the idea that any one of those might have been innocent?" asked moderator Brian Williams. "I’ve never struggled with that at all," was Perry’s response, delivered to an approving audience of conservatives who applauded the number of Texas executions.

But if Perry hasn’t struggled with the application of the death penalty, what about the Catholic justices who hold the power to stop a man’s execution or allow the state to kill him? Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia addressed that question earlier this week in a speech at a Catholic law school in Pittsburgh. "If I thought that Catholic doctrine held the death penalty to be immoral," said Scalia, "I would resign. I could not be a part of a system that imposes it."

Americans Tailor Religion to Fit Their Needs

If World War II-era warbler Kate Smith sang today, her anthem could be Gods Bless America. That's one of the key findings in newly released research that reveals America's drift from clearly defined religious denominations to faiths cut to fit personal preferences.

The folks who make up God as they go are side-by-side with self-proclaimed believers who claim the Christian label but shed their ties to traditional beliefs and practices. Religion statistics expert George Barna says, with a wry hint of exaggeration, America is headed for "310 million people with 310 million religions."

"We are a designer society. We want everything customized to our personal needs — our clothing, our food, our education," he says. Now it's our religion.

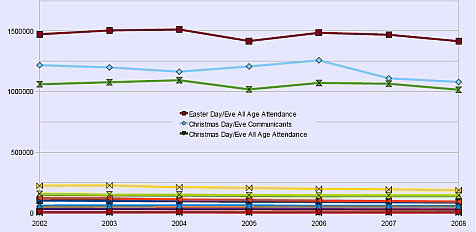

Barna's new book on U.S. Christians, Futurecast, tracks changes from 1991 to 2011, in annual national surveys of 1,000 to 1,600 U.S. adults. All the major trend lines of religious belief and behavior he measured ran downward — except two. More people claim they have accepted Jesus as their savior and expect to go to heaven.

And more say they haven't been to church in the past six months except for special occasions such as weddings or funerals. In 1991, 24% were "unchurched." Today, it's 37%. Barna blames pastors for those oddly contradictory findings. Everyone hears, "Jesus is the answer. Embrace him. Say this little Sinners Prayer and keep coming back. It doesn't work. People end up bored, burned out and empty," he says. "They look at church and wonder, 'Jesus died for this?'" The consequence, Barna says, is that, for every subgroup of religion, race, gender, age and region of the country, the important markers of religious connection are fracturing.

Pope Benedict XVI: British Riots Linked To 'Moral Relativism'

VATICAN CITY (RNS) Pope Benedict XVI linked last month's riots in England to the corrosive effects of "moral relativism," and warned that preserving social order requires government policies based on "enduring values."

Benedict made his remarks on Friday (Sept. 9) to Britain's new Vatican ambassador, Nigel M. Baker, at a meeting in the papal summer residence at Castel Gandolfo, outside Rome.

The moral basis of government policies is "especially important in the light of events in England this summer," Benedict said, in an apparent reference to riots in London and other English cities last month, which left five people dead and caused at least 200 million pounds ($320 million) in property damage.

"When policies do not presume or promote objective values, the resulting moral relativism ... tends instead to produce frustration, despair, selfishness and a disregard for the life and liberty of others," the pope said.

Benedict called on government leaders to foster the "essential values of a healthy society, through the defense of life and of the

family, the sound moral education of the young, and a fraternal regard for the poor and the weak."

The pope's words echoed remarks by British Prime Minister David Cameron, who said last month that the riots were a consequence of his nation's "slow-motion moral collapse."

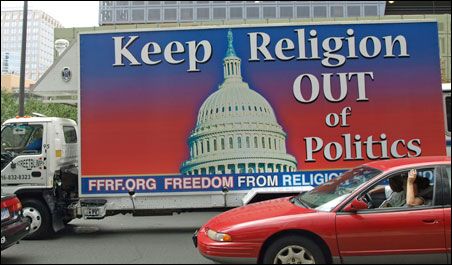

What Journalists Should Be Asking Politicians About Religion

A few weeks ago, I opened up my Twitter feed early in the morning and immediately wondered if I was being punk’d. Instead of the usual horse race speculation, my colleagues in the political press corps were discussing the writings of evangelical theologian Francis Schaeffer and debating the definition of Dominionism. The same week, a conservative journalist had posed a question about submission theology in a GOP debate, and David Gregory had grilled Michele Bachmann about whether God would guide her decision-making if she became President.

The combination of religion and politics is a combustible one. And while I’m thrilled to see journalists taking on these topics, it seemed to me a few guidelines might be helpful in covering religion on the campaign trail:

Ask relevant questions.

The New York Times‘ Bill Keller published a column last weekend calling for journalists to ask candidates "tougher questions about faith" and posing a few of his own. The essay was flawed on its own terms. It read like a parody of an out-of-touch, secular, Manhattan journalist–comparing religious believers to people who believe in space aliens, and referring to evangelical Christian churches as "mysterious" and "suspect." But it also identified the wrong problem. It’s not necessarily tougher questions that are needed but more relevant questions than journalists normally pose. It’s tempting to get into whether a Catholic candidate takes communion or if an evangelical politician actually thinks she speaks to God. But if a candidate brings up his faith on the campaign trail, there are two main questions journalists need to ask: 1) Would your religious beliefs have any bearing on the actions you would take in office? and 2) If so, how?Values Added

Southern Baptist Edition

Amy Sullivan and Richard Land talk about Southern Baptists

Is the religious right dead? And is that a stupid question? (06:13)

Richard: Perry is Bush on steroids (02:24)

Why Southern Baptists hate Obamacare (02:40)

The Christian case for comprehensive immigration reform (08:31)

What do voters deserve to know about a politician’s faith? (07:20)

Questions for Obama about his Christian faith (03:23)

NYT Editor's Column on Religious Faith Sparks Firestorm

A New York Times column by outgoing Executive Editor Bill Keller has unleashed a hailstorm of online criticism among religious bloggers and conservative activists. The fact that the column compares religious believers to folks who think that space aliens are residing on Earth is just the beginning. Keller’s column, "Asking Candidates Tougher Questions About Faith," argues that the crop of candidates competing for the White House next year should be grilled on their religious beliefs and on how those beliefs inform their political views.

That’s especially true, Keller reasons, because many of this year’s GOP contenders hail from "churches that are mysterious or suspect to many Americans." Here’s Keller:

"Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman are Mormons, a faith that many conservative Christians have been taught is a "cult" and that many others think is just weird. … Rick Perry and Michele Bachmann are both affiliated with fervid subsets of evangelical Christianity — and Rick Santorum comes out of the most conservative wing of Catholicism — which has raised concerns about their respect for the separation of church and state, not to mention the separation of fact and fiction."

One of the Timesman’s key concerns is that these candidates will put their religious faith first - above the national interest and the laws of the land:

"I do want to know if a candidate places fealty to the Bible, the Book of Mormon (the text, not the Broadway musical) or some other authority higher than the Constitution and laws of this country. … I care a lot if a candidate is going to be a Trojan horse for a sect that believes it has divine instructions on how we should be governed."

To that end, Keller announces that he has sent customized questionnaires to handful of Republican presidential candidates, with questions like, "Do you agree with those religious leaders who say that America is a "Christian nation" or a "Judeo-Christian nation?" and what does that mean in practice?"

We Can't Forgive, We Can Only Pretend To

Evolutionary doctrine teaches us that it's in our own self-interest to co-operate and to put up with others.

Forgiveness is impossible. This was the thought of the philosopher Jacques Derrida, and he has a good point.

There are some things that we say are easy to forgive. But, Derrida argues, they don't actually need forgiving. I forget to reply to an email, and my friend remarks: "Oh, it didn't really matter anyway." It's not that he forgave me. He'd forgotten about the email too.

Then, there are other things we say are hard to forgive, and we admire those who appear to be able to forgive nonetheless. The case of Rais Bhuiyan, who was shot by Mark Stroman, is a case in point. Bhuiyan says he forgave Stroman, and asked the Texas authorities not to execute him for his crime. But did Bhuiyan really forgive?

He writes of how Stroman was ignorant and had a terrible upbringing. He had seen signs that Stroman was now a changed man. So, it does not seem that Bhuiyan forgave his assailant. Rather, he came to understand him. He saw the crime from the perpetrator's point of view. There were reasons for the wrongdoing. That lets Stroman off the hook. It's not really forgiveness.

CS Lewis wrote: "Everyone says forgiveness is a lovely idea, until they have something to forgive." Which is again to imply that those who think they have offered forgiveness really find they don't have anything to forgive after all.

The ancient philosophers appear to have thought that forgiveness is something of a pseudo-subject, too. They hardly touched on it, for all that they dwelt on all manner of other moral concerns. It is not on any list of virtues. Take Aristotle. He wrote about pardoning people, but only when they are not responsible. "There is pardon," he says, "whenever someone does a wrong action because of conditions of a sort that overstrain human nature, and that no one would endure." When nature has not been overstrained, justice must meet wrongdoing. Forgiveness doesn't come into it.

All this calls into question a theory in evolutionary psychology. Here, the argument is that forgiveness is essential to our evolutionary success. It's because we forgive one another that we are able to live in large groups. People in collectives like cities are bound to offend one another all the time, the theory goes. It's because we are so ready to forgive and continue to co-operate that we don't, as a rule, destroy ourselves in spirals of retribution.

Explain it to me: Ramadan

No food? No drinking? No sex? It's the Muslim month of Ramadan. CNN Religion Editor Dan Gilgoff explains.

Carl Jung, Part 8: Religion and the search for meaning

Jung thought psychology could offer a language for grappling with moral ambiguities in an age of spiritual crisis.

In 1959, two years before his death, Jung was interviewed for the BBC television programme Face to Face. The presenter, John Freeman, asked the elderly sage if he now believed in God. "Now?" Jung replied, paused and smiled. "Difficult to answer. I know. I don't need to believe, I know."

What did he mean? Perhaps several things.

He had spent much of the second half of his life exploring what it is to live during a period of spiritual crisis. It is manifest in the widespread search for meaning – a peculiar characteristic of the modern age: our medieval and ancient forebears showed few signs of it, if anything suffering from an excess of meaning. The crisis stems from the cultural convulsion triggered by the decline of religion in Europe. "Are we not plunging continually," Nietzsche has the "madman" ask when he announces the death of God. "Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us?"

Jung read Nietzsche and agreed that it was. The slaughter of two world wars and, as if that were not enough, the subsequent proliferation of nuclear weaponry were signs of a civilisation swept along by unconscious tides that religion, like a network of dykes, once helped contain. "A secret unrest gnaws at the roots of our being," he wrote, an unrest that yearns for the divine. Nietzsche agreed that God still existed as a psychic reality too: "We godless anti-metaphysicians still take our fire … from the flame lit by a faith that is thousands of years old." And now the flame is out of control.

The sense of threat – real and imagined – that Jung witnessed during his lifetime has not lessened. Ecologists such as James Lovelock now predict that the planet itself has turned against us. Or think of the war games that power an online gaming industry worth £45bn and counting. Why do so many spend so much indulging murderous fantasies?

You could also point to the proliferation of new age spiritualities that take on increasingly fantastical forms. One that interested Jung was UFOs: the longing for aliens – we are without God but not without cosmic companions – coupled to tales of being "chosen" for abduction, are indicative of mass spiritual hunger.

Italy's Family Ties

Rome's austerity package threatens the country's traditional social structure.

Today the Italian parliament will vote on an austerity package designed to reduce its budget by roughly €40 billion over the next three years. The move comes under pressure from international bond markets, whose fears about government debt in wake of the Greek debacle have threatened to provoke a crisis in the euro zone's third largest economy.

While the most politically controversial proposals aren't unique to the Italian austerity plan, cuts in pensions and increased medical fees, one provision points to a long-term social change that is dramatically transforming Italy's economy.

Part of the package places a new tax on Italian divorces. There would be a €37 fee for every uncontested dissolution, which increases to €85 whenever a judge must settle disagreements over property or custody. Just a few years ago, this levy would have brought in a trivial amount of revenue. In 1995, there were only 80 divorces for every 1,000 marriages in Italy. In 2009, that number reached 181 and is still on the rise. Government estimates suggest that the tax will bring in €10.5 million in its first three years.

Italians will pay for divorce in more than taxes. The decline of the traditional family will mean the disappearance of their greatest social service provider. Even at the height of its postwar largesse, the Italian welfare state never matched the cradle-to-grave care of northern European countries. Anyone who has used Italian public services knows that they are usually inadequate without any contributions (financial or in-kind) from relatives.

According to Francesco Billari, a professor of demography at Milan's Bocconi University, some 30% of Italian grandparents provide day care for at least one grandchild. On average, this is a far higher share than in other Western European countries, which spend 40% more than Italy on these types of services.

Carl Jung, Part 6: Synchronicity

With physicist Wolfgang Pauli, Jung explored the link between the disparate realities of matter and mind.

The literary agent and author Diana Athill describes the genesis of one of her short stories. It occurred about nine one morning, when she was walking her dog. Crossing the road, a car approached and slowed down. She presumed someone needed directions. A man leaned out and brazenly asked her whether she would like to join him for coffee.

That was odd enough, so early in the day. More oddly still, the man powerfully reminded her of someone else. He looked just like a lost friend and, further, the daring approach was just the kind of thing her friend would have done. She couldn't stop thinking about the coincidence. It left her feeling " energised and strange," a flow that kept bubbling up until she channelled it, producing the short story.

It is an example of what Jung called synchronicity, "a coincidence in time of two or more causally unrelated events which have the same or similar meaning" – in Athill's case, the surprising invitation of the man and his looking like her friend. Anecdotally, it seems that such experiences are familiar to many. They are undoubtedly meaningful and produce tangible effects too, like short stories. But they raise a question: is the relationship between the events random or is some hidden force actively at work? Jung pursued this question in an odd relationship of his own, with one of the great physicists of the 20th century, Wolfgang Pauli. The story of their friendship is related by Arthur I Miller, in "137: Jung, Pauli, and the Pursuit of a Scientific Obsession."

Pauli was a Jekyll and Hyde character, a Nobel theorist by day and sometime drunk womaniser by night. He turned to Jung when he could no longer hold the competing aspects of his life together. Jung was always fascinated by personality splits, and his analysis helped to steady Pauli. They began working together in a collaboration that lasted for several decades, though mostly behind closed doors: Pauli worried for his reputation, though eventually they published a book together.

Presidential Race and Religion

The first of the blockade-busting flotilla of boats bound for Gaza has set off; there are fears of a repeat of the violence last year which led to the death of nine protesters. The BBC's Yolande Knell describes the mood in Jerusalem.

Two weeks ago, we joined Symon Hill as he set off on a walk of repentance from Birmingham to London. Symon finishes his walk this weekend and he will tell William about his journey.

Files have revealed that a Christian socialist group, which had the future Archbishop of Canterbury as one of its members, was being watched by MI5 and was called 'the most subversive group in the Church'. William finds out more about it with two of the group's former members.

The race for the Republican Presidential nomination is hotting up, and the religion of the two front runners is playing a big factor. William speaks to US political analyst Mark Pinsky and author Tricia Erickson.

What effect has one posting on YouTube of a female had on the role of women in the strict kingdom of Saudi Arabia? We'll hear from women's rights activist Hala Al Dosari.

listen now or download Listen now: Radio 4

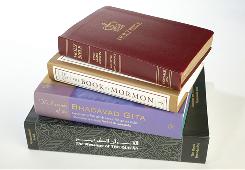

CNN Accurately Explains Beliefs and Misconceptions of LDS Church

Misconceptions about Mormons were cleared up accurately, but not by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Dan Gilgoff, CNN's religion editor, posted a video called "Explain it to me: Mormonism." The video covers basic Mormon beliefs, but mostly focuses on common misconceptions on topics like polygamy.

"Ever since 1890, the official Mormon Church has banned polygamy," Gilgoff said. "Polygamists in the church today are actually excommunicated from the church."

He goes on to explain the FLDS is a "breakaway sect that continues to practice polygamy to this day."

Gilgoff runs down a list of basic LDS beliefs, including its beginnings in 1830, the translation of The Book of Mormon, the physical characteristics of God, continuing revelation and the eternal perpetuation of the family.

He specifically focuses on the missionary work of the church. He points out that Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman Jr. have served missions.

"For Huntsman, he was assigned to Taiwan as a missionary, and it helped him acquire the Chinese language skills, which later helped him land the job as President Obama's ambassador to China," Gilgoff said.

He claims the LDS Church has a "tradition or an image of being seen as a very white-bread church," but the church is working hard to move away from that. He references Mormon.org, the church's missionary outreach website, which shows Mormons from different ethnic backgrounds.

The Dalai Lama, Marxist?

The brave spiritual leader's unusual blind spot.

Earlier this month, the Dalai Lama told a group of Chinese students at the University of Minnesota, "I consider myself a Marxist . . . but not a Leninist." The comment struck some as odd—as if Lindsey Lohan had declared herself a Shaker. Students in the audience looked puzzled. One blogger wondered "if Pope Benedict and other world religious leaders are soon to follow."

But those who have followed His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, know that he regularly trots out a Marxist banner. When he came to Radio City Music Hall to lecture for a few days last year, he announced "Still I am a Marxist" even while thanking his good friends in the Chinese Communist Party for bringing capitalist freedoms to their land.

That stance leads to some head-scratching. Isn't this esteemed 75-year-old Nobel Peace Laureate the former "Boy King" who fled Mao's Chinese forces in 1959? Isn't he the 50-year exile whose fellow Tibetans suffered genocide, after some 20% of them died at the hands of Chinese forces or from starvation? Isn't Marxism a godless secular thing, and the Dalai Lama himself a manifestation of God on earth? If he doesn't know Marxism is false, who does?

The Dalai Lama explained his youthful enthusiasm in a 1999 essay for Time, mentioning that he even considered joining the Communist Party: "Tibet at that time was very, very backward. The ruling class did not seem to care, and there was much inequality. Marxism talked about an equal and just distribution of wealth. I was very much in favor of this. Then there was the concept of self-creation. Marxism talked about self-reliance, without depending on a creator or a God. That was very attractive. . . . I still think that if a genuine communist movement had come to Tibet, there would have been much benefit to the people."

It's an old, familiar position in Western secular intellectual life: Marxism wasn't a God that failed, and the Soviet Union and Mao's China don't count against it, because Marxism was never tried—Communism perverted it. The problem is that Marx wasn't just a Marxist—he was a Communist—and many of Mao's most destructive moves came right out of Marx's playbook for destroying self-reliance, among other things.

Ten Things the BeliefBlog Learned in its First Year

In case you were wondering about all the balloons and cake: CNN’s Belief Blog has just marked its first birthday.

After publishing 1,840 posts and sifting through 452,603 comments (OK, we may have missed one or two) the Belief Blog feels older than its 12 months would suggest. But it also feels wiser, having followed the faith angles of big news stories, commissioned lots of commentary and, yes, paid attention to all those reader comments for a solid year.

10 things we've learned:

1. Every big news story has a faith angle.

Even the ordeal of 33 Chilean miners trapped underground for more than two months. Even the attempted assassination of Arizona congresswoman Gabby Giffords. Even March Madness . Even – well, you get the point.

2. Atheists are the most fervent commenters on matters religious.

This became apparent immediately after the Belief Blog's first official post last May, which quickly drew such comments as:Values Added

It's the Religion, Stupid

Amy Sullivan and Melinda Henneberger chat about religion.

Values Added: It’s the Religion, Stupid

Just how Mormon is Jon Huntsman? (08:21)

"Big Love" and the mainstreaming of Mormonism (05:31)

The real meaning of "Obama is a Muslim" (09:53)

Family values face-off: Bachmann vs. Palin (03:11)

The anti-Boehner protest at Catholic University (11:43)

Setting the record straight on Paul Ryan and Archbishop Dolan (08:01)

In Search of Happily Ever After

When Indian steel tycoon Pramod Agarwal married off his daughter Vinita in Venice last weekend, the entertainment included stilt-walkers, fireworks, two Indian elephants and a 45-minute private concert by the Colombian pop star Shakira. Reports in the Italian press (which, it must be said, tends to err on the side of hyperbole) put the cost of the three-day affair as high as €20 million.

Few of the 10,000 foreign couples expected to marry in Italy this year are likely to rival the Agarwal nuptials for lavishness. Yet if past trends continue, these "destination" weddings will enrich the national economy by at least €180 million—not counting airfare and post-celebration spending by the newlyweds and their guests.

These figures come from Paolo Nassi, general manager of the Regency Travel Group, which has organized weddings of foreigners in Italy since 1987. Destination weddings are a business that has defied recent downturns in the wider tourism industry, Mr. Nassi says. The annual number of such events here has more than doubled since the beginning of the century, compared with the previous decade.

It's not just that getting married is something that ideally happens only once, and thus an unlikely candidate for the budget-cutter's axe. Getting married abroad can actually be an economical move, since it normally means entertaining fewer guests than at a reception thrown back home. Mr. Nassi says that saving money is the single most common reason his clients give for coming to Italy to wed. Choosing to spend on a honeymoon instead of a big party might seem flagrantly un-Italian. Weddings here, especially in the south, are traditionally proud displays of a family's prosperity (or willingness to take on debt), with a guest list that amounts to an exhaustive roster of one's clan and social network. But that costly custom has spawned a no-less-characteristically Italian tradition known in Sicilian dialect as the fuitina: an elopement, supposedly undertaken to defy the opposition of the couple's families, but often planned with their tacit agreement to spare the expense of a wedding. In that case, the only extravagance on view is the in-laws' show of feigned outrage.

Vatican Opens Dialogue With Atheists

VATICAN CITY (RNS) A new Vatican initiative to promote dialogue between believers and atheists debuted with a two-day event on Thursday and Friday (March 24-25) in Paris.

"Religion, Light and Common Reason" was the theme of seminars sponsored by the Vatican's Pontifical Council for Culture at various locations in the French capital, including Paris-Sorbonne University and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

"The church does not see itself as an island cut off from the world ... Dialogue is thus a question of principle for her," Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi told the French newspaper La Croix. "We are aware that the great challenge is not atheism but indifference, which is much more dangerous."

The events were scheduled to conclude with a party for youth in the courtyard of the Cathedral of Notre Dame on Friday evening (March 25), featuring an appearance via video by Pope Benedict XVI, followed by prayer and meditation inside the cathedral.

The initiative, called "Courtyard of the Gentiles," takes its name from a section of the ancient Temple of Jerusalem accessible to non-Jews, which Benedict has used as a metaphor for dialogue between Catholics and non-believers.

Buddhism is the New Opium of the People

Western Buddhism has a long path to travel before becoming something that resists, rather than supplements, consumerism.

In one of the many living rooms that belong to David and Victoria Beckham, there sits a four-feet-high golden statue of the Buddha. Madeleine Bunting spotted it on TV, she told a packed audience for the last of the Uncertain Minds series. What is it about Buddhism, she mused, that makes it such a perfect fit with modern consumerism?

The Buddhist writer Stephen Batchelor who, along with the Buddhist scholar John Peacock, was speaking at the event, replied that there is a temple in Thailand that contains a Buddha rendered as a small image of David Beckham. The symmetry is perfect. And it raises a vital question for western Buddhism.

Western Buddhism presents itself as a remedy against the stresses of modern life though, as Slavoj Žižek has noted, it actually functions as a perfect supplement to modern life. It allows adherents to decouple from the stress, whilst leaving the causes of the stress intact: consumptive forces continue unhindered along their creatively destructive path. In short, Buddhism is the new opium of the people.

Batchelor and Peacock might agree that this is a serious charge and grave risk. And their efforts can be interpreted as precisely to resist it.

Their analysis is different. Western Buddhism is undergoing its Protestant reformation, Batchelor observed. It is about two centuries behind western Christianity in terms of its critical engagement with its canonical texts. The quest for the historical Buddha – an exercise that parallels the 19th-century quest for the historical Jesus – is only just under way. An essentially medieval Buddhism has been catapulted into modernity. It's hardly surprising that it will take two, perhaps three centuries for an authentically western form to emerge – by which is meant, in part, one that resists, not supplements, consumerism. For if Buddhism is to live in the modern world, it must be treated as a living tradition, not a preformed import. As the reformation leaders of the 16th century knew, this is a profoundly unsettling project – though it is also compelling for its promise is new life.

How Japan’s Religions Confront Tragedy

Proud of their secular society, most Japanese aren't religious in the way Americans are: They tend not to identify with a single tradition nor study religious texts.

"The average Japanese person doesn’t consciously turn to Buddhism until there’s a funeral," says Brian Bocking, an expert in Japanese religions at Ireland’s University College Cork.

When there is a funeral, though, Japanese religious engagement tends to be pretty intense.

"A very large number of Japanese people believe that what they do for their ancestors after death matters, which might not be what we expect from a secular society," says Bocking. "There’s widespread belief in the presence of ancestors’ spirits."

In the days and weeks ahead, huge numbers of Japanese will be turning to their country’s religious traditions as they mourn the thousands of dead and try to muster the strength and resources to rebuild amid the massive destruction wrought by last Friday's 9.0 magnitude earthquake and resulting tsunami.

For most Japanese, religion is more complex than adhering to the country’s ancient Buddhist tradition. They blend Buddhist beliefs and customs with the country’s ancient Shinto tradition, which was formalized around the 15th century.

"Japanese are not religious in the way that people in North America are religious," says John Nelson, chair of theology and religious studies at the University of San Francisco. "They’ll move back and forth between two or more religious traditions, seeing them as tools that are appropriate for certain situations."

"For things connected to life-affirming events, they’ll turn to Shinto-style rituals or understandings," Nelson says. "But in connection to tragedy or suffering, it’s Buddhism."

There are many schools of Japanese Buddhism, each with its own teachings about suffering and what happens after death.

Pope Benedict Beatifies His Star Predecessor

The current pontiff lacks the presence and popularity of John Paul II, the former actor and Cold Warrior.

When Pope Benedict XVI declares Pope John Paul II "blessed" on May 1, bestowing on his predecessor the Catholic Church's highest honor short of sainthood, millions will watch from St. Peter's Square, on television and on the Internet. John Paul's beatification, which was officially announced last week, will be an occasion for recalling his eventful reign, and it will inevitably inspire comparisons with the man who now sits in his place. In many eyes, those comparisons will not prove favorable to Benedict.

The current pope is low-key, as Americans discovered during his 2008 visit. For all his charm, he lacks the gregariousness, physical presence and gift for the dramatic gesture with which the former actor John Paul could win over crowds.

Although a clearer and more accessible writer than John Paul, Benedict is far less at home in the age of electronic communications. His reign has been marked by a chain of public-relations disasters, most recently the widespread confusion over his remarks about the morality of condom use.

John Paul was also a much more commanding leader than his successor. It is impossible to imagine the late pope giving an interview of the kind that Benedict granted the German journalist Peter Seewald last year, in which he repeatedly admitted personal error and suggested that he is largely impotent to enforce many of his own policies within the church.

Nor has Benedict matched his predecessor's popularity among non-Catholics. An enthusiastic participant in inter-religious dialogue of all kinds, John Paul appealed to Muslims and Jews with historic apologies for Christian anti-Semitism and the sins of Catholics during the Inquisition and the Crusades.

The current papacy has been marked by heightened tensions with Muslims and Jews. Benedict's 2006 address in Regensburg, Germany, in which he quoted a medieval description of the teachings of Islam's prophet Muhammad as "evil and inhuman," was followed by violent protests in several Muslim countries. Benedict has also irritated Jews by readmitting an ultra-traditionalist bishop who turned out to be a Holocaust denier, and by honoring Pope Pius XII, who critics say failed to do or say enough against the Nazi genocide.

How a Marxist Might See the Creed

My take on Terry Eagleton's interpretation of Christianity unites it with Marxism in a rejection of progress.

For the latest event in the Uncertain Minds series, I talked with the Marxist critic Terry Eagleton, author of Reason, Faith, and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate. We were sitting beneath the stone arches of the Wren suite, in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral. And as we conversed, I had a very odd experience. It was as if I could hear him reciting a Christian creed – sotto voce – adding in his distinctive gloss on several of the key phrases. Here's something close to what I imagined he said.

I believe in God. Obviously, if I were a Christian, I wouldn't believe in God in the way that an alarming proportion of Americans believe in alien abduction. After all, Satan believes in God in that sense. He knows God exists. But he doesn't trust in God and isn't committed to God's ways. Quite the opposite. Alain Badiou, probably the greatest philosopher alive today, writes about having a commitment to a revelatory event. That must be more like what a Christian believes.

Creator of heaven and earth. This, of course, has absolutely nothing to do with the big bang. Those who are tempted to think of it as a reference to divine pyrotechnics on a cosmic scale should read a little Wittgenstein. Creator-talk is theology, and that's a different language game from science. Rather, to call God the creator means that you believe the universe has a purpose. As to how it was done – physics has a few ideas. As to what that purpose might be – well, we perhaps glean something from the next line.

I believe in Jesus Christ. Jesus is the locus for a remarkable set of stories. They are remarkable because they remember a life that clung to faith even when the subject of that life was hanging half dead from a tree. As my sometime fellow papist Marxist, Herbert McCabe, once put it: if you don't love you die, if you do love they kill you. In this tragic world of ours, that seems to me to be quite true. And remember, tragedy is not the same as pessimism because pessimism gives up hope, which is precisely what Jesus didn't do. Though he had more reason than most to do so.

Army's 'Spiritual Fitness' Test Angers Some Soldiers

Multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan have taken a toll on soldiers: Witness the rise in suicides and other stress-related disorders. A few years ago, the Army noticed that some soldiers fared better than others, and it wondered: Why?

One reason, says Brig. Gen. Rhonda Cornum, is that people who are inclined toward spirituality seem to be more resilient.

"Researchers have found that spiritual people have decreased odds of attempting suicide, and that spiritual fitness has a positive impact on quality of life, on coping and on mental health," says Cornum, who is director of Comprehensive Soldier Fitness.

'Foxhole Atheist' Upset

Working with psychological researchers, the Army developed a survey to assess a soldier's family relationships and his well-being — emotionally, socially and spiritually. Every soldier was required to take the survey, including Justin Griffith, a sergeant at Fort Bragg, N.C.

Griffith, who describes himself as a "foxhole atheist," says he grew angry as the computerized survey asked him to rank himself on statements such as: "I am a spiritual person. I believe that in some way my life is closely connected to all of humanity. I often find comfort in my religion and spiritual beliefs."

"The next question was equally shocking," Griffith says. " 'In difficult times, I pray or meditate.' I don't do those things, and I don't think any of those questions have anything to do with how fit I am as a soldier."

Griffith finished the survey, pressed submit, and in a few moments, he received an assessment: "Spiritual fitness may be an area of difficulty."

listen now or download Listen to the Story: All Things Considered

11 Faith-Based Predictions for 2011

To open 2011, CNN's Belief Blog asked 10 religious leaders and experts - plus one secular humanist - to make a faith-based prediction about the year ahead.

Have a faithy prediction of your own? Share it in comments.

Here's what those in the know are predicting:

1. With the repeal of "don't ask, don't tell" there will be a more concerted effort by the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgendered community for gay marriage, uniting conservative evangelicals, Roman Catholics, Muslims and Orthodox Jews in a much more civil but principled resistance. Respectful debate will produce more precise and pluralistic solutions.

–Dr. Joel C. Hunter, senior pastor of Northland, a Church Distributed, in Orlando, Florida

2. A new generation of Muslims will bust out of their culturally and politically isolated cocoons and passionately reclaim their voice and narratives; one that has been stolen, used, abused and hijacked by extremists, terrorists and fear-mongering propagandists. Watch out for a major cultural renaissance as a new generation of Muslim artists and storytellers grab the mic, enter the arena and speak their voice with a revived passion and purpose.

–Wajahat Ali, Muslim playwright and attorney

3. As anti-Christian violence accelerates in places like Iraq, Egypt and India, a government crackdown on Christian churches gathers steam in China, and European bureaucrats continue to drive Christianity from the public square, "Christianophobia" will become a buzzword.

–John Allen Jr., CNN's senior Vatican analyst

4. After years of increasingly contentious debates and billboard wars between religious believers and atheists, American secularists will begin to embrace a message of positive humanist community, gaining increasing acceptance as they organize cooperation between nontheists and theists toward the common good.

–Greg M. Epstein, humanist chaplain at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts

5. As religious tensions grow over the coming presidential election and domestic cultural issues involving perceived legislation of morality, the media will find more zealous Christians reacting to the issues of the day whose extreme positions will further divide the evangelical church into radical positions, and turn away seekers looking for a peaceful resolution to the churning in their own souls. In other words, the devil will play a trick on the church, and the church will, like sheep, lose their focus on the grace and love of Christ and wander astray. Those who seek peace, then, will turn to liberal ideologies.

–Don Miller, Christian author whose books include "Blue Like Jazz"

Walking Santa, Talking Christ

Why do Americans claim to be more religious than they are?

Two in five Americans say they regularly attend religious services. Upward of 90 percent of all Americans believe in God, pollsters report, and more than 70 percent have absolutely no doubt that God exists. The patron saint of Christmas, Americans insist, is the emaciated hero on the Cross, not the obese fellow in the overstuffed costume.

There is only one conclusion to draw from these numbers: Americans are significantly more religious than the citizens of other industrialized nations.

Except they are not.

Beyond the polls, social scientists have conducted more rigorous analyses of religious behavior. Rather than ask people how often they attend church, the better studies measure what people actually do. The results are surprising. Americans are hardly more religious than people living in other industrialized countries. Yet they consistently—and more or less uniquely—want others to believe they are more religious than they really are.

Religion in America seems tied up with questions of identity in ways that are not the case in other industrialized countries. When you ask Americans about their religious beliefs, it's like asking them whether they are good people, or asking whether they are patriots. They'll say yes, even if they cheated on their taxes, bilked Medicare for unnecessary services, and evaded the draft. Asking people how often they attend church elicits answers about their identity—who people think they are or feel they ought to be, rather than what they actually believe and do.

The better studies ascertain whether people attend church, not what they feel in their hearts. It's possible that many Americans are deeply religious but don't attend church (even as they claim they do). But if the data raise serious questions about self-reported church attendance, they ought to raise red flags about all aspects of self-reported religiosity. Besides, self-reported church attendance has been held up as proof that America has somehow resisted the secularizing trends that have swept other industrialized nations. What if those numbers are spectacularly wrong?

To the data: There was an obvious clue (in hindsight) that the survey numbers were hugely inflated. Even as pundits theorized about why Americans were so much more religious than Europeans, quiet voices on the ground asked how, if so many Americans were attending services, the pews of so many churches could be deserted.

"If Americans are going to church at the rate they report, the churches would be full on Sunday mornings and denominations would be growing," wrote C. Kirk Hadaway, now director of research at the Episcopal Church. (Hadaway's research has included evangelical congregations, which reported sharp growth in recent decades.)

All-American Grace

More than 20 years ago, an elderly, foreign-born Catholic priest told me, "You can't imagine how different it was here when I first came here in the '60s. Catholics and Protestants didn't really talk to each other. It's so much better now."

He was talking about clerics, mostly, but it was still startling news to me. I was born in the late '60s, around the time this priest moved to town. Sure, we Protestants had our suspicions about what Catholics really believed, but to keep them at a social distance? People really did that once? It was about as bizarre to folks of my generation as the thought that blacks and whites were once segregated by law. A year after my conversation with the old priest, I joined a parish class of inquirers seeking conversion to Catholicism, but left angry and discouraged after three months of regular meetings. We'd had lots of guided meditation and feel-good talks, but no doctrine, no substance, nothing solid.

I complained to a Catholic friend that all of us were going to become Catholics at Easter, but only those of us who had educated ourselves with outside reading were going to have the slightest idea what being a Catholic required of us. My sympathetic friend gave me the number of a crusty old Irish priest who had been stored away in a small inner-city parish.

"By the time I get through with you," said Father Moloney, in his chewy Irish brogue, "you might not want to be a Catholic, but you'll know what a Catholic is." I knew then that I was in good hands. That old-school priest grasped that Catholicism made various exclusive truth claims, and that it was important for potential converts to understand what they were assenting to before conversion. The priest at the other parish only seemed to care that his convert class have good feelings about being Catholic.

Those two anecdotes illustrate both the good news and the bad news in American Grace, the indispensable new portrait of U.S. religious life drawn by Harvard's Robert D. Putnam and Notre Dame's David E. Campbell, two of the nation's leading social scientists. The good news is that we Americans of different faith traditions get along remarkably well, not by casting aside religion, but by learning how to be tolerant even as we remain religiously engaged.

The bad news is that achieving religious comity has come at the price of religious particularity and theological competence. That is, we may still consider ourselves devoted to our faith, but increasingly, we don't know what our professed faith teaches, and we don't appreciate why that sort of thing is important in the first place.

William James and Agnosticism

Just how far will it get us if we resolve never to act beyond what the evidence allows?

Brian Zamulinski provided a long and thoughtful response to William James's case for jumping ahead of the evidence. He argued firstly that "Overbelief" can cause tremendous harm to others, as it did in Stalin's Russia, and secondly that we cannot know in advance how much harm will be caused to others by any belief unjustified by the evidence. It would follow that the only safe course is to avoid altogether believing beyond what the evidence allows.

Now the stipulation that overbelief is to be shunned because it can cause harm to others, rather than to the person who believes ahead of the evidence, is a shrewd and subtle attempt to rescue the Clifford position, and to shift it away from James' criticisms.

After all, no one who believes in an evolutionary account of religion can seriously suppose that overbelief has in the past caused more harm than "underbelief": waiting to act until the evidence is irresistible. If you believe, as I do, that we have an overdeveloped agency detection system that enables us to apprehend life and purpose where there is none, and that this is a product of evolution, this is pretty irrefutable evidence that waiting to see if that rustle in the grass really was a tiger was more harmful than jumping to conclusions and into the nearest tree. No doubt this was harmful to those more evidence-based hominids who waited to be certain that the rustling was a tiger, but it was good for our ancestors, who jumped.

The kind of harm that Zamulinski argues against is much more directly caused by overbelievers. To believe in the triumph of "scientific socialism", no matter what real science said, did kill tens of millions of people. In fact the history of Stalinism provides a paradigm case for evidence-based caution – at least among Western intellectuals. The people we admire in their response to Stalinism are the ones who refused to be taken in: Bertrand Russell, Orwell, Koestler, even Muggeridge, who all modified their initial romantic expectations in the light of experience and stuck to the truth of their disillusionment whatever the subsequent persecutions.

Two Views of Likely Catholic Leader

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops gathers in Baltimore this week to decide who will be its next president, and if past is prologue, we know who will win: Bishop Gerald Kicanas of Tucson, Ariz. But this year, what is usually a rote decision is garnering a flurry of debate.

Kicanus is seen as an easygoing diplomat who prefers digging into policy papers over hogging the spotlight. And he's popular.

"In his diocese, he's seen as one of the most effective bishops in the country," says Rocco Palmo, a close observer of the Catholic Church, who writes the blog "Whispers in the Loggia".

Palmo says Kicanas earned that reputation after 2003, when he became bishop of Tucson, where he inherited a diocese rife with sex abuse allegations and on the brink of bankruptcy.

"While some dioceses have struggled — and it's been an acrimonious time — the Tucson bankruptcy under Kicanas' leadership has been seen as a national model," Palmo says.

The bankruptcy judge publicly praised Kicanas for treating the victims well spiritually and financially, Palmo says, and in a vote of confidence, donations to the bishop's appeal outstripped their expectations a year after the bankruptcy.

That's one view of Kicanas. Another is held by Terry McKiernan, who runs the watchdog group BishopsAccountability.org and says practically every bishop in the pipeline for the presidency has been tainted by the sex abuse scandal.

listen now or download NPR Morning Edition

Values Added: The Praying Field

Amy: Democrats foolishly conceded the faith vote (05:02)

When pastors say you can’t be a Democrat and a good Christian (06:11)

Does Tom Perriello’s narrow loss point the way forward? (07:18)

Oklahomans vote against the looming scourge of Shariah law (05:50)

The growing idea that Islam isn’t a real religion (03:24)

Glenn Beck, Pamela Geller, and innovations in hatred (11:47)

The Postmodern Condition: The Assault on Truth from Left to Right (video)

Vancouver Sun columnist Peter McKnight looks at how postmodernism - a left wing theory that promotes skepticism of truth - is now being championed by those on the right.

Hitchens Brothers Agree To Disagree Over God

JJournalist Christopher Hitchens is one of the world's most famous atheists. His brother, Peter, insists that a civilized world must believe in God. The brothers have publicly argued over faith for years. But now that Christopher Hitchens has been diagnosed with cancer, the theoretical argument has become real. Just how real was apparent at the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, where the brothers were having a public conversation about God. Christopher Hitchens often wears a white straw hat. He says his head, completely bald from chemotherapy treatments, gets cold. He's tired. He's thin. He's off his food.

But ask Hitchens, author of "God Is Not Great," if having cancer has changed his view of religion or God. "If anything, my contempt for the false consolation of religion has increased since I became aware that I probably don't have very long to live," he replies.

Since Hitchens' cancer diagnosis in June, he has received thousands of letters and e-mails, some from believers asserting that he's getting what he deserves, more from people saying they're praying for his recovery. Hitchens says he has been overwhelmed by the outpouring. But he is annoyed that some writers hope he'll have a last-minute conversion to Christianity. "Under no persuasion could I be made to believe that a human sacrifice several thousand years ago vicariously redeems me from sin," he says. "Nothing could persuade me that that was true — or moral, by the way. It's white noise to me."

His brother, Peter, is equally blunt: "There is actually no absolute right or wrong if there is no God," he says. Peter once shared his older brother's views; he burned his Bible when he was a teenager in boarding school. But as he chronicled in his book, "The Rage Against God" — which he wrote as a response to his brother's anti-religious book — he felt drawn back to his Anglican faith starting in his late 20s.

He says his work as a journalist in Somalia and the former Soviet Union convinced him that civilization without religious morality devolves into brutality. Moral behavior requires more than higher reasoning, he says; it requires God. "It seems to me to be very, very, very hard to come up with an atheistic explanation of conscience any more than you can have a compass with a magnetic north," he says. "If the magnetic north kept shifting, then it would be very difficult to steer your boat or your plane across the Atlantic."

listen now or download Listen to the Story: Morning Edition

'God Views' and Issues

Experts say Americans are divided on imagining God's personality and behavior, views that shape our response to momentous events and contentious issues.

If you pray to God, to whom — or what — are you praying?

When you sing God Bless America, whose blessing are you seeking?

In the USA, God — or the idea of a God — permeates daily life. Our views of God have been fundamental to the nation's past, help explain many of the conflicts in our society and worldwide, and could offer a hint of what the future holds. Is God by our side, or beyond the stars? Wrathful or forgiving? Judging us every moment, someday or never?

Surveys say about nine out of 10 Americans believe in God, but the way we picture that God reveals our attitudes on economics, justice, social morality, war, natural disasters, science, politics, love and more, say Paul Froese and Christopher Bader, sociologists at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. Their new book, America's Four Gods: What We Say About God — And What That Says About Us, examines our diverse visions of the Almighty and why they matter.

Based primarily on national telephone surveys of 1,648 U.S. adults in 2008 and 1,721 in 2006, the book also draws from more than 200 in-depth interviews that, among other things, asked people to respond to a dozen evocative images, such as a wrathful old man slamming the Earth, a loving father's embrace, an accusatory face or a starry universe.

Most Americans Believe in God....

But don't know religious tenets.

Americans are clear on God but foggy on facts about faiths.

The new U.S. Religious Knowledge Survey, released today by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, finds that although 86% of us believe in God or a higher power, we don't know our own traditions or those of neighbors across the street or across the globe.

Among 3,412 adults surveyed, only 2% correctly answered at least 29 of 32 questions on the Bible, major religious figures, beliefs and practices. The average score was 16 correct (50%).

Key findings:

•Doctrines don't grab us. Only 55% of Catholic respondents knew the core teaching that the bread and wine in the Mass become the body and blood of Christ, and are not merely symbols. Just 19% of Protestants knew the basic tenet that salvation is through faith alone, not actions as well.

•Basic Bible eludes us. Just 55% of all respondents knew the Golden Rule isn't one of the Ten Commandments; 45% could name all four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John).

•World religions are a struggle. Fewer than half (47%) knew that the Dalai Lama is a Buddhist; 27% knew most people in Indonesia are Muslims.

"People say, 'I have a personal connection with God and that's really all I need to know.' Who am I to argue?" says Pew's Alan Cooperman, a co-author of the report.

But religion, as a force in history and a motivator in present times, "has consequences in the world," he adds, so an intellectual baseline, whatever your faith or lack of faith, can "shape your role as a citizen in the public square."

The top scoring groups were atheists/agnostics, Jews and Mormons. These tiny groups, adding up to less than 7% of Americans, scored particularly well on world religion and U.S. constitutional questions. It's unclear why, although highly educated people overall did best on the quiz, researchers say.

"Catholic Guilt," "Jewish Guilt," not Just a Joke, but Essential

Guilt gets a bad rap as a relentless joke: Catholic guilt. Jewish guilt. Mormon guilt. Even Lutherans have guilt, or, some say, guilt envy. We dub our trivial naughtiness "guilty pleasures" to put a little frosting on those thorns of conscience.

But as Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement nears (it begins at sunset Friday), experts say guilt is not passé, it's essential — and probably inescapable.

"Guilt has been with us as long as humans have psyches, "but we still don't know definitively how it works in the human psyche or the best way to deal with it," says Temple University psychology professor Frank Farley, former president of the American Psychological Association.

Even so, Farley, faith writers and clergy say the best response to guilt is to face up, embrace it — then let it go.

Rabbi David Wolpe of Sinai Temple in Los Angeles offers a defense of guilt.

Facing up to the hurt we cause others with cruel speech or callous acts, and to our myriad failures to meet the marks God sets for living a true and good life, "makes forgiveness meaningful, not merely a catchphrase," Wolpe says.

"If you hurt someone, then the least you could do is feel bad. That's what moral responsibility looks like," adds evangelical writer Philip Yancey, author of a new book, What Good is God? Of course, you don't have to be religious to feel guilt.

Teaching Young American Muslims

Late last month, the 15 students who comprise Zaytuna College's inaugural class settled in to their first day in a classroom near the University of California, Berkeley. For these students, this is a chance to study with top Islamic scholars. For the school's founders, it's a chance to hone a new image for American Islam.

I don't know what I expected to find when I arrived at Zaytuna College in Berkeley, Calif., the country's brand new Muslim liberal arts college. Women in headscarves? Yes, for the most part. Men with heavy beards? No. A lot of prayer and fasting, since it's Ramadan? Absolutely.

What I didn't expect was 24-year-old Jamye Ford.

"I grew up as an AME, African-American Episcopal, in a very religious Southern family," Ford says in the campus quad. "I went to church every Sunday for hours at a time, I went to Bible study, did all of those things. And from a young age, I had curiosity about religion in general and other religions."

Ford bought a Quran at a secondhand bookstore when he was 9 and memorized a few sura or passages, which he always remembered. He entered Columbia University at 16 and graduated with a double major in neuroscience and history. But he was drawn to the poetry of the Quran, and this summer, he began studying Arabic at Zaytuna.

Tell All the Truth Slant

"Tell all the truth, but tell it slant," wrote the poet Emily Dickinson: "Success in circuit lies." The advice is itself a truth, a commendation in the art of looking sideways.

Dickinson lived in an age when it was becoming impossible to find truth straightforwardly, if ever there has been such a time. In her generation, the Victorian crisis about belief in God peaked. Philosophers announced the death of God. Naturalists challenged what had always seemed to be the best evidence for God: nature’s apparent design.

What is striking about Dickinson, though, is that she both experienced the darkness of that doubt, and found a way to transform it into an experience that produced meaning. It’s all about the pursuit of the circuitous.

That her medium was poetry is no mere detail. It is almost the whole story. Poetry not only allows her to express herself – her desire for consolation, her anxiety about what’s disappearing. It is also the form of writing par excellence that can keep an eye open for what is peripheral. It can discern truths that words otherwise struggle to articulate. It glimpses, and hopes.

She was born in 1830, and although her poems are now widely available, most of her work was not published in her own lifetime. That was partly because she lived as a recluse. In the later part of her life, she even refused to leave her room. But she had, no less, many friends and was as prolific a letter-writer as she was a poet.

Values Added: Religious Persuasions

How the press botched the story of the murdered missionaries (11:45)

Debating the strategies of gay marriage advocates (18:23)

Is the "Ground Zero mosque" full of holy fools? (05:24)

Politicians fanning anti-Islam flames (07:31)

What’s behind Uganda’s anti-homosexuality bill (06:04)

Anne Rice quits Christianity, enrages Amy (05:17)

Out-of-Body Experiences

A couple of days before the government announced that the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) will be axed, the journal Human Reproduction published a report on why, nearly 40 years ago, the UK Medical Research Council refused to fund Patrick Steptoe's and Robert Edwards's attempt to produce a test-tube baby.

One surprising factor was that they weren't part of the in-crowd: Steptoe "came from a minor northern hospital" and Edwards wasn't even a professor. Properly shocking, however, is the news that the refusal came in part because government research was focused on limiting fertility, rather than increasing it. If ever we questioned the need for an "arm's-length" body to distance government policy from reproductive science, surely that little bombshell is enough to make us think again.

No doubt fertility clinics are rejoicing at the HFEA news. Scientists, if they know what's good for them, won't be. The HFEA was designed not to deal with the minutiae of regulating clinics, but to facilitate a public appraisal of the dilemmas that science creates.

The regulation of fertility and embryology research will now be hidden within the remit of the Care Quality Commission (CQC). There will be repercussions. These are life-and-death issues, and people care far more about them than whether the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust is reducing the incidence of bedsores (the subject of a recent CQC press release). Without a distinct, visible body to oversee reproductive ethics, scientists in the field stand to lose public trust.

The HFEA has tackled some daunting issues in its time. Remember Diane Blood, who wanted to be impregnated using her dead husband's frozen sperm? The child, now nearly 12, was conceived and born despite the HFEA's disapproval. Perhaps the HFEA didn't get that right, but

it has made some good calls, too.

In 2004, the UK became the first European nation to permit research on cloned human cells. In 2007, scientists breathed a sigh of relief when the HFEA permitted women to donate eggs for research projects under certain circumstances. Another sensible decision, transparently made.

What was right in every case was that a high-profile public debate took place; scientists were not given carte blanche. Will this continue when reproductive ethics is a minor part of the CQC's remit?

Christian Academics: Hostility on Campus

One of the hot debates in academia is now reaching the courts. The question: Do universities discriminate against religious conservatives? Some professors and students say they do, but it's not an easy charge to pin down.

When Elaine Howard Ecklund began asking top scientists whether they believe in God, she got a surprise. Ecklund, an assistant professor at Rice University and author of the book Science Vs. Religion, polled 1,700 scientists at elite universities. Contrary to the stereotype that most scientists are atheists, she says, nearly half of them say they are religious. But when she did follow up interviews, she found they practice a "closeted faith."

"They just do not want to bring up that they are religious in an academic discussion. There's somewhat of almost a culture of suppression surrounding discussions of religion at these kinds of academic institutions," Ecklund says.

She says the scientists worried that their colleagues would believe they were politically conservative — or worse, subscribed to the theory of intelligent design. Ecklund says they all insisted on anonymity.

Fewer Evangelicals In Academia

And it appears that climate may extend beyond science departments. A poll of 1,200 academics by the Institute for Jewish and Community Research found that more than half said they have unfavorable feelings toward evangelical Christians. Aryeh Weinberg, who co-authored the study, says one reason for this is that there are relatively few evangelicals in academia.

"The question is, why? Do they self-select out, and if they do, why are they self-selecting out? Are they actually not hired? Are they trying to get hired but not getting hired? Are they getting hired then being forced out, not getting tenure?" Weinberg asks.

Randall Balmer, a professor of American religious history at Columbia University and an Episcopal priest, disagrees. "I haven't encountered that hostility at all," Balmer says. "I've been a visiting professor at places like Emory and Northwestern and Yale and Princeton and other places. And I simply have not encountered that sort of hostility to my claims of faith or my professions of faith."

listen now or download All Things Considered

- listen… []

Clinton-Mezvinsky Wedding Reflects Mix of Religions in USA

Chelsea Clinton, a Methodist, and Marc Mezvinsky, a Conservative Jew, had their very private wedding on Saturday. But the public may not be done peering through the shrubbery at their lives.

Like it or not, the famous bride and groom will continue to be the focus of scrutiny for their religiously mixed marriage — a category that's

growing rapidly among U.S. couples.

Two decades ago, 25% of U.S. couples didn't share the same faith. That was up to 31% by 2006-08, according to the General Social Survey by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago. The number was even higher, 37%, in the 2008 U.S. Religious Landscape Survey by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. Both surveys included people who crossed major traditions, such as Jewish-Protestant, believers married to the unaffiliated, and Protestants of different denominations, such as former president Bill Clinton, a Baptist, and Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, a Methodist.

For those of nominal faith, this is no big deal. "Everybody party" is a popular way to avoid doctrinal conflicts, however thin on theology. But for those who hold deep but different faiths, life-cycle decisions will loom, from baptism (No? Yes? Whose church?) to burial (Can you rest in sacred ground of another faith?). Every rite of passage, sacred ritual and major holy day will require negotiation: First Communion? Bar or bat mitzvah? Passover Seder, Easter vigil or Eid Al-Fitr feast to break Islam's Ramadan fast?

Looking on: Parents and clergy who fear that distinctive beliefs, sacred rituals and centuries-old cultural traditions will be diluted or discarded.

Is True Friendship Dying Away?

To anyone paying attention these days, it's clear that social media — whether Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn or any of the countless other modern-day water coolers — are changing the way we live.

Indeed, we might feel as if we are suddenly awash in friends. Yet right before our eyes, we're also changing the way we conduct relationships. Face-to-face chatting is giving way to texting and messaging; people even prefer these electronic exchanges to, for instance, simply talking on a phone.Smaller circles of friends are being partially eclipsed by Facebook acquaintances routinely numbered in the hundreds. Amid these smaller trends, growing research suggests we could be entering a period of crisis for the entire concept of friendship. Where is all this leading modern-day society? Perhaps to a dark place, one where electronic stimuli slowly replace the joys of human contact.

Awareness of a possible problem took off just as the online world was emerging. Sociologist Robert Putnam published the book Bowling Alone, a survey of the depleting levels of "social capital" in communities, from churches to bowling allies. The pattern has been replicated elsewhere in the Western world. In the United Kingdom, the Mental Health Foundation just published The Lonely Society, which notes that about half of Brits believe they're living in, well, a lonelier society. One in three would like to live closer to their families, though social trends are forcing them to live farther apart.

Typically, the pressures of urban life are blamed: In London, another poll had two-fifths of respondents reporting that they face a prevailing drift away from their closest friends. Witness crowded bars and restaurants after work: We have plenty of acquaintances, though perhaps few individuals we can turn to and share deep intimacies. American sociologists have tracked related trends on a broader scale, well beyond the urban jungle. According to work published in the American Sociological Review, the average American has only two close friends, and a quarter don't have any.

No One Left to Pray To?

If God occasionally intervenes in the world to shoot down an atheist—to show who's boss, or simply to vent—it makes sense for Him to target the esophagus.

As organs go, it's long and conveniently placed, stretching from throat to stomach, making a good target for an elderly yet determined deity with possibly shaky hands. Its importance to speech heightens the symbolic force intended. And its connection to swallowing suggests the irony some believers think God enjoys too much: You can't swallow me? You won't swallow anything!

For atheist apostle and recent memoirista Christopher Hitchens, who announced on June 30 that he'd cancel the rest of his Hitch-22 book tour to undergo chemotherapy on said cancerous organ, the argument for such personalized intelligent design presumably doesn't hold. Hitch does recognize the role of vengeance and ressentiment in believer/nonbeliever relations, but only in fueling institutions established by believers further down the Great Chain of Being. "Religion," he wrote in God Is Not Great, "does not, and in the long run cannot, be content with its own marvelous claims and sublime assurances. It must seek to interfere with the lives of nonbelievers, or heretics, or adherents of other faiths."

One thing's for sure—Hitch is not in great health. Indeed, he faces the possibility of not being at all if the chemo proves useless. Should believers pray for him, a man celebratedly insensitive to norms of politeness and acts of altruism? He is, after all, the same character who, in The Missionary Position (1995) and elsewhere (a film, Hell's Angel, and numerous author appearances), deemed Mother Teresa "the ghoul of Calcutta." To Hitchens, the "world's best-known symbol of selfless charity" (as The Philadelphia Inquirer once described her) evinced "a penchant for the rich and famous, no matter how corrupt and brutal." Hitch is also the stern moralist who judged onetime Oxford acquaintance Bill Clinton, who's done a few good deeds in his time, as "indescribably loathsome," a phony with "no one left to lie to." Hitchens is the self-appointed judge and jury who found Nobel Peace Prize winner Jimmy Carter "a pious, born-again creep," and Jewish philosopher Martin Buber a "pious old hypocrite."

Within a week of Hitchens's announcement, 1,619 people offered comments on Huffington Post's report of his bad news. Another 335 kicked in on his own Vanity Fair blog. Hundreds of comments appeared on the personal site of one woman who set out a formal argument for why Christians should pray for Hitchens.

Obama's 10 Most Important Faith Leaders

Even before Barack Obama was elected president, religious figures loomed large in his political career. The greatest threat to his presidential campaign came not from another candidate but from his longtime pastor, Jeremiah Wright, whose controversial sermons prompted questions about Obama's judgment in associating with him. After Election Day, the first big controversy of the Obama era was the president-elect's invitation to evangelical preacher Rick Warren, an opponent of abortion rights and gay marriage, to give the opening prayer at his inauguration. And Obama has offered religious leaders an unusually prominent role in his administration by convening an advisory council for the White House faith-based office that's dominated by clergy and heads of religious groups.

In an administration that keeps in touch with hundreds of faith leaders, here are the 10 most important.

THE REV. JOEL HUNTER: Pastor of Northland Church, Longwood, Fla.

The Rev. Joel Hunter's resignation as president-elect of the Christian Coalition in 2006 over disagreements about the organization's strictly hot-button agenda turned him into an emblem of a new generation of evangelicals, one that toes the conservative line on abortion but embraces progressive causes like environmentalism. A megachurch pastor based near Orlando, Hunter was among the evangelical leaders whom Obama courted on the campaign trail last year. Hunter delivered the benediction at the Democratic National Convention and has since emerged as a top faith-based surrogate for the president, defending him on matters as diverse as embryonic stem cell research and his selection of Kathleen Sebelius as health and human services secretary. The White House consulted him in drafting Obama's recent address to the Muslim world.

THE REV. JIM WALLIS: President and Executive Director of Sojourners

Progressive evangelical Jim Wallis has been a political oddity ever since he landed in Washington more than 35 years ago. Lobbying for poverty relief and against war, Wallis was at odds with Christian right leaders who claimed to speak for evangelical America. His politics lined up with the Democrats, but the party had little use for evangelical pastors. As younger evangelicals have branched out beyond hot-button issues and Democrats have begun wooing born-again Christians, however, Wallis is suddenly very much in demand.

Richard Dawkins's Backward Logic over Atheist Schooling

Richard Dawkins's belief that any properly brought up child will naturally be an atheist leads him into absurdity.

Richard Dawkins on Mumsnet came up with a remark to silence all his critics: "What have you read of mine that makes you think I have a skewed agenda?" It certainly left me opening and shutting my mouth like a breathless goldfish. Actually the whole thread is worth reading: it is from here that the story has come forth that he wants to start an atheist school. Whether that will actually happen is another thing. But it is in any case revealing of his reasoning. (There doesn't seem to be a way to link to individual comments on Mumsnet, but all these quotes are cut and pasted from the thread.)

He was asked by one commenter:

"What would you say to parents of children who attend quite orthodox state-funded schools who are very anxious that their child be educated within that context? I am thinking specifically of the ortho-Jewish schools around my way (north London). I know for a fact a lot of these parents cannot countenance the idea of their child being educated within a non-Jewish school. What do you think they should do?"

His response was:

"That's a good point. I believe this is putting parental rights above children's rights."