World & Mind

Human Consciousness is Much More than Mere Brain Activity

When we meditate or use our powers of perception, we call on more than just a brain.

How does the animated meat inside our heads produce the rich life of the mind? Why is it that when we reflect or meditate we have all manner of sensations and thoughts but never feel neurons firing? It's called the "hard problem", and it's a problem the physician, philosopher and author Raymond Tallis believes we have lost sight of – with potentially disastrous results.

In his new book, Aping Mankind – about which he was talking this week at the British Academy – he describes the cultural disease that afflicts us when we assume that we are nothing but a bunch of neurons. Neuromania arises from the doctrine that consciousness is the same as brain activity or, to be slightly more sophisticated, that consciousness is just the way that we experience brain activity.

If you think the brain is a machine then you are committed to saying that composing a sublime poem is as involuntary an activity as having an epileptic fit. You will issue press releases announcing "the discovery of love" or "the seat of creativity", stapled to images of the brain with blobs helpfully highlighted in red or blue, that journalists reproduce like medieval acolytes parroting the missives of popes. You will start to assume that the humanities are really branches of biology in an immature form.

What is astonishing about this rampant reductionism is that it is based on a conceptual muddle that is readily unpicked. Sure, you need a brain to be alive, but to be human is not to be a brain. Think of it this way: you need legs to walk, but you'd never say that your legs are walking. The same conflation can be exposed in a more complex way by reflecting on the phenomenon of perception. It is what we do every moment of the waking day. You're doing it right now: casting an eye to the paper in front of you and seeing words on a page. But if you were just a brain, you would not see words. There'd be just the gentle buzz of neuronal activity in the intracranial darkness.

Carl Jung, Part 3: Encountering the Unconscious

Jung's Red Book reveals his belief in the painful, personal process of discovering how the unconscious manifests itself in conscious life

Jung's split with Freud in 1913 was costly. He was on his own again, an experience that reminded him of his lonely childhood. He suffered a breakdown that lasted through the years of the first world war. It was a traumatic experience. But it was not simply a collapse. It turned out to be a highly inventive period, one of discovery. He would later say that all his future work originated with this "creative illness".

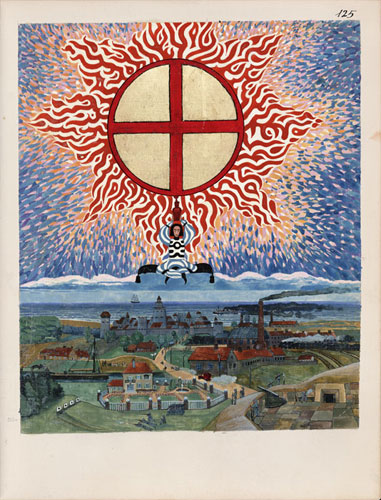

He experienced a succession of episodes during which he vividly encountered the rich and disturbing fantasies of his unconscious. He made a record of what he saw when he descended into this underworld, a record published in 2009 as The Red Book. It is like an illuminated manuscript, a cross between Carroll's Alice in Wonderland and Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

Its publication sparked massive interest in Jungian circles, rather like what happens in Christian circles when a new first-century codex is discovered. It is of undoubted interest to scholars, in the same way that the notebooks of Leonardo are to art historians. And it is an astonishing work to browse, for its intricacy and imagination. But it is also highly personal, which is presumably why Jung decided against its publication in his own lifetime. So, to turn it into a sacred text, as some appear inclined to do, would be a folly of the kind Jung argued against in the work that followed his recovery from the breakdown.

In particular he wrote two pieces, known as the Two Essays, that provide a succinct introduction to his mature work. (He can otherwise be a rambling, elusive writer.) On the Psychology of the Unconscious completes his separation from Freud. He shows how tracing the origins of a personal crisis back to a childhood trauma, as Freud was inclined to do, might well miss the significance of the crisis for the adult patient now.

In The Relations between the Ego and the Unconscious, he describes a process whereby a person can pay attention to how their unconscious life manifests itself in their conscious life. It will be a highly personal and tortuous experience. "There is no birth of consciousness without pain," he wrote. But with it, the individual can become more whole.

By way of illustration, Jung considers the example of a man whose public image is one of honour and service but who, in the privacy of his home, is prone to moods – so much so that he scares his wife and children. He is leading a double life as public benefactor and domestic tyrant. Jung argues that such a man has identified with his public image and neglected his unconscious life – though it won't be ignored and so comes out, with possibly explosive force, in his relations with his family. The way forward is to pay attention to this inner personality, literally by holding a conversation with himself. He should overcome any embarrassment in doing so and allow each part of himself to talk to the other so that both "partners" can be fully heard.

Carl Jung, part 2: A troubled relationship with Freud – and the Nazis

On the 50th anniversary of Jung's death it is time to put accusations of him collaborating with the Nazis to rest.

Jung's relationship with Freud was ambivalent from the start. First contact was made in 1906, when Jung wrote about his word association tests, realising that they provided evidence for Freud's theory of repression. Freud immediately and enthusiastically wrote back. But Jung hesitated. It took him several months to write again.

They met a year later and then it was friendship at first sight. The two talked non-stop for 13 hours. Freud called Jung "the ablest helper to have joined me thus far", and spoke of how Jung would be good for psychoanalysis as he was a respected scientist and a protestant – a dark observation that was to haunt Jung three decades later when the Nazis came to power.

For now, different tensions persisted. A request Jung made highlights one axis of difficulty: "Let me enjoy your friendship not as one between equals but as that of father and son," he wrote. The originator of the Oedipus situation, in which murderous undertones supposedly exist between a father and a son, was alarmed. Freud did anoint Jung his "son and heir", but he also experienced a series of neurotic episodes revealing the fear that Jung was a threat too.

One such incident occurred when they travelled together to America in 1909. Conversation turned to the subject of the mummified corpses found in peat bogs, which prompted Freud to accuse Jung of wanting him dead. He then fainted. A similar thing happened again a while later.

A different sign of conflict came when Jung asked Freud what he made of parapsychology. Sigmund was a complete sceptic: occult phenomena were to him a "black tide of mud". But as they were sitting talking, Jung's diaphragm began to feel hot. Suddenly, a bookcase in the room cracked loudly and they both jumped up. "There, that is an example of a so-called catalytic exteriorisation phenomenon," Jung retorted – referring to his theory that the uncanny could be projections of internal strife. "Bosh!" Freud retorted, before Jung predicted that there would be another crack, which there was.

All in all, from early on, Jung was nagged by the thought that Freud placed his personal authority above the quest for truth. And behind that lay deep theoretical differences between the two.

Carl Jung, Part 1: Taking Inner Life Seriously

Achieving the right balance between what Jung called the ego and self is central to his theory of personality development.

If you have ever thought of yourself as an introvert or extrovert; if you've ever deployed the notions of the archetypal or collective unconscious; if you've ever loved or loathed the new age; if you have ever done a Myers-Briggs personality or spirituality test; if you've ever been in counselling and sat opposite your therapist rather than lain on the couch – in all these cases, there's one man you can thank: Carl Gustav Jung.

The Swiss psychologist was born in 1875 and died on 6 June 1961, 50 years ago next week. His father was a village pastor. His grandfather – also Carl Gustav – was a physician and rector of Basel University. He was also rumoured to be an illegitimate son of Goethe, a myth Carl Gustav junior enjoyed, not least when he grew disappointed with his father's doubt-ridden Protestantism. Jung felt "a most vehement pity" for his father, and "saw how hopelessly he was entrapped by the church and its theological teaching", as he wrote in his autobiographical book, Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

Jung's mother was a more powerful figure, though she seems to have had a split personality. On the surface she came across as a conventional pastor's wife, but she was "unreliable", as Jung put it. She suffered from breakdowns. And, differently again, she would occasionally speak with a voice of authority that seemed not to be her own. When Jung's father died, she spoke to her son like an oracle, declaring: "He died in time for you."

In short, his childhood was disturbed, and he developed a schizoid personality, becoming withdrawn and aloof. In fact, he came to think that he had two personalities, which he named No 1 and No 2.

No 1 was the child of his parents and times. No 2, though, was a timeless individual, "having no definable character at all – born, living, dead, everything in one, a total vision of life". (At school, his peers seem to have picked this up, as his nickname was "Father Abraham".)

Inside the "Black Box" of Personhood

Notre Dame sociologist Christian Smith asks, "What is a person?"

Notre Dame sociologist Christian Smith recently spoke with Big Questions Online about his new book What Is A Person?

What is a person? And why does it matter how we answer that question?

Every social science explanation has operating in the background some idea or other of what human persons are, what motivates them, what we can expect of them. Sometimes that is explicit, often it is implicit. And the different concepts of persons assumed by social scientists have important consequences in governing the questions asked, sensitizing concepts employed, evidence gathered, and explanations formulated. We cannot put the question of personhood in a "black box" and really get anywhere. Personhood always matters. By my account, a person is "a conscious, reflexive, embodied, self-transcending center of subjective experience, durable identity, moral commitment, and social communication who — as the efficient cause of his or her own responsible actions and interactions — exercises complex capacities for agency and inter-subjectivity in order to develop and sustain his or her own incommunicable self in loving relationships with other personal selves and with the non-personal world."

Persons are thus centers with purpose. If that is true, then it has consequences for the doing of sociology, and in other ways for the doing of science broadly. Different views of human personhood will provide us with different scientific interests, different professional moral and ethical sensibilities, different theoretical paradigms of explanation, and, ultimately, different visions of what comprises a good human existence which science ought to serve. In this sense, science is never autonomous or separable from basic questions of human personal being, existence, and interest. Therefore, if we get our view of personhood wrong, we run the risk of using science to achieve problematic, even destructively bad things. Good science must finally be built upon a good understanding of human personhood.

You argue that the standard sociological view of the human person isn’t sufficient, that sociologists generally do not capture the fullness of human experience with their methods. Indeed, you describe them as living with a kind of "schizophrenia" – believing strongly in a human rights and dignity, but at the same time denying any kind of grounding for those moral commitments. What are they missing?

Many, if not most, sociological theories operate with an emaciated view of the person running in the background, models that are grossly oversimplified. Persons are conceptualized as rational reward-maximizers or compliant norm-followers or essentially meaning-seekers or genetic-reproduction machines or whatever else. Often such views are one-dimensional and simplistic. They fail to even begin to portray the complexity and richness of human personal life. Meanwhile, sociologists going about living their own personal lives with often a very different view of humanity in mind. The science does not live up to the reality. I think this is often driven not by the needs of real science but by a kind of insecure scientism. The former is ultimately interested in knowing what is real and how it works, however complex that might turn out to be. The latter, especially in the social sciences, is often mostly concerned to imitate the science of an entirely different sphere of reality, such as physics, which never turns out well.

How to Meditate: An Introduction

'Mindfulness meditation' – getting to know the here and now – could be the key to a calmer, happier, healthier you.

Rates of depression and anxiety are rising in the modern world. Andrew Oswald, a professor at Warwick University who studies wellbeing, recently told me that mental health indicators nearly always point down. "Things are not going completely well in western society," he said. Proposed remedies are numerous. And one that is garnering growing attention is meditation, and mindfulness meditation in particular.

The aim is simple: to pay attention – be "mindful". Typically, a teacher will ask you to sit upright, in an alert position. Then, they will encourage you to focus on something straightforward, like the in- and out-flow of breath. The aim is to nurture a curiosity about these sensations – not to explain them, but to know them. There are other techniques as well. Walking meditation is one, when you pay attention to the soles of your feet. That too carries a symbolic resonance: if breath is to do with life, feet are a focus for being grounded in reality.

It's a way of concentrating on the here and now, thereby becoming more aware of how the here and now is affecting you. It doesn't aim directly at the dispersal of stresses and strains. In fact, it is very hard to develop the concentration necessary to follow your breath, even for a few seconds. What you see is your mind racing from this memory to that moment. But that's the trick: to observe, and to learn to change the way you relate to the inner maelstrom. Therein lies the route to better mental health.

Mindfulness, then, is not about ecstatic states, as if the marks of success are oceanic experiences or yogic flying. It's mostly pretty humdrum. Moreover, it is not a fast track to blissful happiness. It can, in fact, be quite unsettling, as works with painful experiences, to understand them better and thereby get to the root of problems.

Research into the benefits of mindfulness seems to support its claims. People prone to depression, say, are less likely to have depressive episodes if they practice meditation. Stress goes down. But it's more like going on a journey than taking a pill. Though meditation techniques can be learned quickly, it's no instant remedy and requires discipline. That said, many who attend lessons or go on retreats find immediate benefits – which is not so surprising, given that in a world of no stillness, even a little calm goes a long way.

William James, Part 8: Agnosticism and Pragmatic Pluralism

William James wanted a philosophy that rested on experience, not logic, because life exceeds logic.

"The most important thing about a man," wrote Chesterton, "is his philosophy." William James agreed. He was fond of quoting the saying. Our philosophy, or "over-belief", shapes our "habits of action," which is to say our ethos – who we are becoming. Pragmatism, the philosophy of "what works," is taken to be James' philosophy. And yet, his pragmatism is different from that of his confrères.

Pragmatism is often associated with deflationary accounts of truth. Truth, with a capital T, is a pipe dream, it implies. No fact, rule or idea is ever certain – nor is even the possibility of facts, rules and ideas. Philosophy and science can make progress, but only in relation to current experience. "Truth is the opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate", wrote one pragmatist philosopher, John Dewey. Or as Richard Rorty pithily averred: "Time will tell, but epistemology won't." When it comes to religion, such pragmatism implies that theologians are more like poets than metaphysicians. They are aestheticians – conjuring meaning with their descriptive powers, as opposed to capturing Truth in their formularies.

It's called ironic pragmatism. "There is an all" is inverted to "that's all there is." Such a stance requires the philosopher, or scientist, to be committed to finding the truth as it if existed, though it probably doesn't. It's truth as a "regulative ideal," to use another phrase. So, if James is a pragmatist, what of his religious quest? Is he condemned to perpetual agnosticism – longing for more and never finding it? It's a big debate amongst Jamesian scholars. But I think his ethos, his philosophy, can be summarised like this.

William James, Part 7: Agnosticism and the Will to Believe

James observes that the idea you can will belief in God is 'simply silly,' as the nature of real assent consists of many strands.

There is an agnostic sensibility that runs through William James – in this sense: he knows that any claim of knowledge based on religious experience could, in principle, be mistaken.

But it may be true, too. He's convinced that the fruits of "spiritual emotions" are morally helpful for humankind, notwithstanding that some fruits become rotten. He's probed mystical experiences – that sense of oneness with the Absolute – to see whether they can decide the case. They can for the individual concerned, he concludes. But, as he observes at the start of lecture 18, mysticism is "too private (and also too various) in its utterances to be able to claim a universal authority". So, in the final sections of the Varieties, the question of whether religious experiences point to objective truth becomes pressing. "Can philosophy stamp a warrant of veracity upon the religious man's sense of the divine?" he asks.

Well, first, you've got to ask what religious philosophy is. It seems obvious to him that it is secondary to religious experience because it is passion, not reason, that fundamentally drives such areas of human inquiry (and quite possibly all areas of human inquiry). Philosophy is necessary, but not sufficient.

In fact, he loathes what he elsewhere calls "vicious intellectualism" – the preference for concepts over reality. It's cultivated by the fantasy of an objective science – and is insidious because it turns you into a spectator of, not a participant in, life. It encourages speculation for speculation's sake, and like the bankers who engage in the financial equivalent, the result is ideological bubbles. They rise high in the intellectual firmament before they burst and crash back to earth. In the sphere of religion, James detects such "vicious intellectualism" most clearly in the attempts to demonstrate the existence of God as an a priori fact. The ontological and cosmological proofs are for those who wish to cleanse themselves of the "muddiness and accidentality" of the world.

Interestingly, he describes the recently beatified John Henry Newman as one such "vexed spirit". He charges the cardinal with a "disdain for sentiment", though I'm not sure that's fair. In fact, Newman seems quite close to James in certain respects, particularly in relation to what Newman called the "grammar of assent".

William James, Part 6: Mystical States

James's discussion of mysticism is not unproblematic, but there is significant value in the way he frames the subject.

Mysticism is a crucial aspect of the study of religion. "One may say truly, I think, that personal religious experience has its roots and centre in mystical states of consciousness," William James writes in The Varieties. That said, it's important to be clear about what he means by phrases like "states of consciousness".

Our view is coloured by a psychologising tendency that's grown since James. It can be associated, in particular, with Abraham Maslow's notion of "peak experiences" – the ecstatic states that satisfy the human need for self-actualisation. This exaltation of feelings of interconnectedness is questionable on two counts.

First, Maslow's analysis is scientifically dubious. As Jeremy Carrette and Richard King put it: "Sampling disillusioned college graduates, Maslow would ask his interviewees about their ecstatic and rapturous moments in life." No offence to students, but they probably do not provide the best samples of mystics.

A second critique of Maslow's work is found in the writings of the great spiritual practitioners themselves. The author of The Cloud of Unknowing, for one, explicitly argues that, whatever the mystical might be, it is hidden from experience. Or, as any decent meditation teacher will tell you, clinging to oceanic experiences will hinder your progress quite as much as clinging to anything else.

This is not to say that mystical experience has nothing to do with feelings, James continues. Rather, it is a state both of feeling and of knowledge, of wonder and intellectual engagement. The two faculties must be deployed when weighing any insight. "What comes," James explains, "must be sifted and tested, and run the gauntlet of confrontation with the total context of experience." Mystical states can, therefore, be assessed for their truth value. But how?

Not, James explains, in the way advocated by the "medical materialists" – those for whom mysticism signifies nothing but "suggested and imitated hypnoid states, on an intellectual basis of superstition, and a corporeal one of degeneration and hysteria".

William James, Part 4: The Psychology of Conversion

Religious conversion, be it sudden or slow, causes a revolution in the personality.

The case of Stephen H Bradley, reported by William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience, is arresting. At the age of 14, he had a vision of Jesus. It lasted only a second. Christ was in the young man's room, "with arms extended, appearing to say to me, Come." From that day on, Bradley called himself a Christian.

Then, when he was in his mid-20s, he attended a revivalist meeting. It left him cold, and that troubled him, as he regarded himself as religious. Then, later that evening, he was gripped by an even more profound experience than the first.

His heart beat fast. He became elated, while also feeling worthless. He experienced a stream of air passing through him. The next morning, he believed he could see "a little heaven upon earth". He visited his neighbours, "to converse with [them] on religion, which I could not have been hired to have done before". He concludes: "I now defy all the deists and atheists in the world to shake my faith in Christ."

Bradley had undergone a religious conversion and, as is his wont, James considers a range of similar cases in the Varieties. They can show a sense of regeneration, or a reception of grace, or a gift of assurance. What distinguishes religious conversion from more humdrum experiences of change is depth. Human beings quite normally undergo alterations of character: we are one person at home, another at work, another again when we awake at four in the morning. But religious conversion, be it sudden or slow, results in a transformation that is stable and that causes a revolution in those other parts of our personality. Hence, before his conversion, Augustine prayed to be chaste but "not yet", which is only to underline that, with his conversion, what was previously impossibility became actual. It's that personal drama that leads the convert to ascribe the change to God.

But, strictly as a psychologist, what sense can be made of it? James resorts to what he believes to have been the greatest discovery of modern psychology, namely that subconscious forces play a defining role in the life of an individual, even when they have no conscious awareness of them.

William James, Part 3: On Original Sin

Are humans born happy, able to create their own well-being, or do we need to be born again to overcome a 'sick soul'?

Original sin is a religious doctrine that divides perhaps more than any other. For some, it only makes sense – maybe not the part about the apple and the garden, but the general idea that humankind is flawed: we do what we wouldn't do, and don't do what we would do, as St Paul put it. For others, though, original sin is vile and offensive. It feeds the fear of hell, a hopelessness about progress, and leaves us pathetically dependent on God. Each side has a radically different view of what it is to be human, and William James understands exactly what's a stake.

It follows from one of the most interesting distinctions he draws in the Varieties. There are some, he explains, who take the happiness that religion gives them to be the amplest demonstration of its truth. Then, there are others who take the remedy that religion offers for the ills of the world to be the amplest reason for its necessity. James adopts the terms "once-born" to describe the happy sort, and "twice-born" for the more pessimistic.

The link between the phrase "once-born" and the positive temperament is that these individuals believe that seeing God – or finding fulfilment, or simply living well – is no more or less difficult than seeing the sun. On some days it will be cloudy. But the skies eventually clear.

The cosmos is fundamentally good, they affirm. Human individuals are, basically, kind. Your first birth, as a baby, is the only birth that's required to see the world aright. This temperament is, James explains, "organically weighted on the side of cheer and fatally forbidden to linger, as those of opposite temperament linger, over the darker aspects of the universe." James's favourite example of the once-born is Walt Whitman. "He has infected [his readers] with his own love of comrades, with his own gladness that he and they exist."

Alongside Whitman, there are some Christians who fall into this category. (Not all take original sin that seriously.) They are of a liberal sort, believing that the significance of Jesus is found in his moral teaching, which if followed would lead to a more perfect world. Popular science-writing has contributed to the increase of this kind of belief too, as it conveys the conviction that human beings can understand themselves and, thereby, fix themselves. Eastern ideas imported into the west offer something similar. Hence, meditation techniques, such as mindfulness, are sold as being scientific and empowering.

Rescuing Evil

Pondering the consciences of Hitler, Hamlet, and England's Psycho-Cabbie Killer

At the close of the final 2010 Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Fellowship seminar series in Cambridge this June, after writer Rob Stein’s informative discussion of "Conscience," as everyone began packing up, one of the moderators, Sir Brian Heap, turned to me and asked (presumably because I’d once written a book entitled Explaining Hitler): "Did Hitler have a conscience, Ron?" Having spent a decade examining that very issue, which was at the heart of my book, I was able to reply, crisply and cogently: "Um, well, I’m not sure . . . I mean, it all depends." Yes, it all depends. It all depends on how you define conscience, and how you define conscience depends on how you define evil, the cancer for which conscience is the soul’s MRI.

Evil has gotten a bad name lately. It always was a name for some sort of badness, yes; but lately the word sounds antiquated, the product of a less-sophisticated age. Evil belongs to an old, superstitious world of black and white, and we all know now that everything is gray, right? It belongs to aworld of blame in which the Enlightenment tells us that "to understand all is to forgive all"—no blame, just explanation. There are some who argue it’s an unnecessary word: Having no ontological reality, no necessary use, it’s merely a semantic trap, a dead end.

After a century that saw the slaughter of more than a hundred million souls, we seem to be insisting on one more casualty: the word evil. Perhaps because by eliminating its accusatory presence and substituting genetic, organic, or psychogenic determinism, we escape the accusatory finger it points at the nature of human nature. Things go wrong with our genes, or our amygdalas, or our parenting, but these are aberrations, glitches. The thing itself, the human soul, is basically good; the hundred million dead, the product of unfortunate but explicable defects, not the nature of the beast.

How William James Offended the English Mind

On the centenary of James's death, is there now more appetite for his pragmatic cherishing of beliefs that are good for life?

Today, in Oxford, a group of academics are trying to right something of a wrong. Meeting in the Rothermere American Institute , they are discussing the work of William James, the psychologist and philosopher whose centenary of death falls this year.

He is well celebrated on the other side of the Atlantic, commentators and academics alike routinely citing him. And he is eminently quotable. In one letter to HG Wells he reflected on "the moral flabbiness born of the exclusive worship of the bitch-goddess success". We are indebted to him for expressions such as "stream of consciousness" too. Some have said he was a better writer than his brother, the novelist Henry James.

But in Europe he's far less visible, which is arguably an oversight, even injustice. It's this argument that the academics in Oxford will be pursuing today.

Why is this so? We can turn to Bertrand Russell for a possible explanation. In his "A History of Western Philosophy," Russell records how James was universally loved as a person. "His religious feelings were very Protestant, very democratic, and very full of the warmth of human kindness," Russell writes. "He refused altogether to follow his brother Henry into fastidious snobbishness." But if Russell is generous about the man, he is less so about the man's philosophy.

James was a tremendous populariser of the philosophy of pragmatism. The principle of pragmatism is, roughly, that something can be said to be true if it works. James wrote: "We cannot reject any hypothesis if consequences useful to life flow from it." This led him to the conclusion that "the true is the name of whatever proves itself to be good in the way of belief". He argued that there is a bridge between our ideas about reality and reality itself, and that our notions about what is true can provide us with the bridge. This is what he meant by what works. So, again, he writes: "Realities are not true, they are; and beliefs are true of them."

There is something about this way of thinking that is offensive to the English mind, and Russell was quick to spot it. He pointed out that the veracity of some truths do not depend upon their efficacy at all. Did not Columbus sail across the Atlantic in 1492? The truth of the date does not depend upon whether his voyage turned out to be good for humanity. But James can defend himself against that retort, since he also argued that the principle of pragmatism comes into its own when there isn't enough evidence to decide whether something is true.

Russell had another line of attack, though, and it was particularly pointed in relation to James's theological views. Religious beliefs are the quintessential case for which there's not enough evidence to decide. The sceptical mind of Russell looks at the evidence for belief in God and, while seeing it's not conclusive, decides that he does not want to believe in God for fear of believing in an error. James, though, has a different thought. He looks at the evidence for belief in God and, while seeing it's not conclusive, feels the force of the duty to believe what's true as well as the duty to avoid error. The sceptic ignores the first part of that duty, which James also called the "will to believe". He noted that while both believer and nonbeliever run the risk of being duped, he thought it was better to be duped "through hope" than "through fear".

Can Your Genes Make You Murder?

When the police arrived at Bradley Waldroup's trailer home in the mountains of Tennessee, they found a war zone. There was blood on the walls, blood on the carpet, blood on the truck outside, even blood on the Bible that Waldroup had been reading before all hell broke loose.

Assistant District Attorney Drew Robinson says that on Oct. 16, 2006, Waldroup was waiting for his estranged wife to arrive with their four kids for the weekend. He had been drinking, and when his wife said she was leaving with her friend, Leslie Bradshaw, they began to fight. Soon, Waldroup had shot Bradshaw eight times and sliced her head open with a sharp object. When Waldroup was finished with her, he chased after his wife, Penny, with a machete, chopping off her finger and cutting her over and over.

"There are murders and then there are ... hacking to death, trails of blood," says prosecutor Cynthia Lecroy-Schemel. "I have not seen one like this. And I have done a lot." Prosecutors charged Waldroup with the felony murder of Bradshaw, which carries the death penalty, and attempted first-degree murder of his wife. It seemed clear to them that Waldroup's actions were intentional and premeditated.

"There were numerous things he did around the crime scene that were conscious choices," Lecroy-Schemel says. "One of them was [that] he told his children to 'come tell your mama goodbye,' because he was going to kill her. And he had the gun, and he had the machete." It was a pretty straightforward case. Even Waldroup said so during his trial last year. He said on the murderous night, he just "snapped," and he admitted that he killed Leslie Bradshaw and attacked his wife. "I'm not proud of none of it," Waldroup said.

"It wasn't a who done it?" says defense attorney Wylie Richardson. "It was a why done it?"

listen now or download All Things Considered

- listen… []

Inside A Psychopath's Brain

The Sentencing Debate

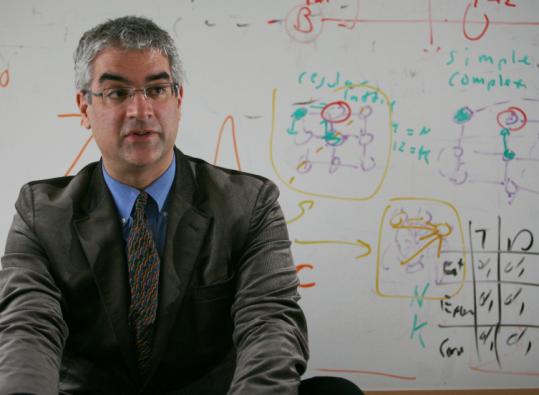

Kent Kiehl has studied hundreds of psychopaths. Kiehl is one of the world's leading investigators of psychopathy and a professor at the University of New Mexico. He says he can often see it in their eyes: There's an intensity in their stare, as if they're trying to pick up signals on how to respond. But the eyes are not an element of psychopathy, just a clue.

Officially, Kiehl scores their pathology on the Hare Psychopathy Checklist, which measures traits such as the inability to feel empathy or remorse, pathological lying, or impulsivity.

"The scores range from zero to 40," Kiehl explains in his sunny office overlooking a golf course. "The average person in the community, a male, will score about 4 or 5. Your average inmate will score about 22. An individual with psychopathy is typically described as 30 or above. Brian scored 38.5 basically. He was in the 99th percentile."

"Brian" is Brian Dugan, a man who is serving two life sentences for rape and murder in Chicago. Last July, Dugan pleaded guilty to raping and murdering 10-year-old Jeanine Nicarico in 1983, and he was put on trial to determine whether he should be executed. Kiehl was hired by the defense to do a psychiatric evaluation.

Kiehl with the brain scanner he uses at prisons. He has scanned the brains of more than 1,100 inmates, about 20 percent of whom are psychopaths.(Barbara Bradley Hagerty)

In a videotaped interview with Kiehl, Dugan describes how he only meant to rob the Nicaricos' home. But then he saw the little girl inside.

"She came to the door and ... I clicked," Dugan says in a flat, emotionless voice. "I turned into Mr. Hyde from Dr. Jekyll."

On screen, Dugan is dressed in an orange jumpsuit. He seems calm, even normal -- until he lifts his hands to take a sip of water and you see the handcuffs. Dugan is smart -- his IQ is over 140 -- but he admits he has always had shallow emotions. He tells Kiehl that in his quarter century in prison, he believes he's developed a sense of remorse.

"And I have empathy, too -- but it's like it just stops," he says. "I mean, I start to feel, but something just blocks it. I don't know what it is."

Kiehl says he's heard all this before: All psychopaths claim they feel terrible about their crimes for the benefit of the parole board.

listen now or download All Things Considered

- listen… []

Who Killed John Lennon?

Science looks at the brain and the law

Who killed John Lennon?

Mark David Chapman, a psychotic, pulled the trigger, assassinating the musician/peace activist in December 1980.

So who killed Lennon, the person or the brain?

That's the kind of question neuroscientists, lawyers and judges are wrestling with today, says Michael Gazzaniga professor of psychology at the University of California, Santa Barbara and head of the SAGE Center for the Study of Mind.

He's leading a project examining brain studies and the law -- the norms of society that are the basis of our rules. Gazzaniga "What is the brain for? It's there to make decisions," he said at a seminar on neuroscience and morality, sponsored by Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Fellowships in Science and Religion where I'm attending lectures and scooping up sources this weekend.

He mused about whether brain scans be accepted in court. What's the veracity of eyewitness testimony? Do we need to revisit the 166-year-old definition of the insanity defense, given what we're learning now about free will and culpability?

After all, most people with brain diseases and conditions, from schizophrenia to people afflicted with tumors and lesions, do not commit crimes and are able to grasp and follow social rules, he says.

However, the brain acquires information and makes decisions well before we are consciously forming choices. Gazzaniga says, "We're all on a little bit of taped delay between unconsciousness and awareness. But none of us believe it. We think we are in charge."

A New Way of Thinking about Social Networks and the World

Our social networks and where we sit in them set the course for much of what happens in our lives, say Nicholas A. Christakis, a doctor and sociology professor at Harvard, and James H. Fowler, a political scientist at the University of California-San Diego.

In their book "Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives’’ they argue that our social networks actually comprise a "super-organism.’’ Our lives take shape not just via those we know, our friends and relations, but through their friends and relations, even if we never meet those people.

You might wonder whether too much time on Facebook has addled their brains. But online social networks have little to do with their theory, and human history offers much to support it. They start the book by looking at feud-driven violence, like revenge killings of extended family members and friends in 19th century Corsica, showing how simply knowing someone can put us in harm’s way.

They then take us on a pleasant walk through interesting research in anthropology, archeology, history, politics, psychology, medicine, and sociometry (the study of social networks). We learn what it means that we evolved primarily in groups of about 150 members, how a social network brought the Medicis to power in Florence and ultimately opened the modern world to democracy, and how Barack Obama’s use of social networking made him president.

They also cite their own 2007 paper arguing that obesity is contagious across social networks. While the authors say their study has been confirmed several times over, even they feel compelled to note that "social network effects are not the only explanation for the obesity epidemic,’’ listing eight others.

Can We Really Build an Artificial Brain?

The four black refrigerator-sized boxes in a basement of the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland bear very little resemblance to a human brain. Each box contains some 2,000 microchips lined up on shelves, rather than the grey matter found inside our heads. However, biologist Henry Markram and colleagues in Lausanne believe that a more powerful version of this computer can simulate the workings of the brain. They say they will be able to create such a simulation within 10 years, that this artificial brain should show the hallmarks of intelligence – such as speech, planning and learning – and that it will simulate emotions and maybe even consciousness. Claims that thinking machines are just round the corner are nothing new. The computer HAL 9000 in Arthur C. Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey was based on predictions by leading scientists about how real-life computers would actually evolve by the turn of the millennium. Indeed, in 1965, artificial intelligence expert Herbert Simon predicted that within 20 years, machines would be capable of "doing any work a man can do".

Of course, such predictions have proved to be woefully wide of the mark, and artificial intelligence, or AI, researchers have suffered frequent funding cuts from skeptical governments. Some predictions have come to pass, such as the forecast that machines would eventually outstrip humans at chess, with IBM's Deep Blue computer beating grandmaster Garry Kasparov in 1997. This success of Deep Blue is, however, not particularly significant in the wider picture. It had no idea of strategy and for each move simply calculated vast numbers of permutations using pre-defined algorithms. It certainly wasn't thinking like a human.

Markram's group says that it differs from previous efforts to mimic human intelligence by simulating the actual biology of the brain. Usually, AI researchers focus on logical structures rather than worrying about messy biology. Artificial neural networks, for example, consist of entities that function like the nervous cells, or neurons, in a brain, in that each receives electrical inputs from a number of

Gray, In Black and White

John Gray's essays are pessimistic, provocative and unsettling. Which is exactly what makes them worth the price of admission.

If John Gray did not exist, it would be necessary, as with Voltaire's God, to invent him. But, as with Voltaire's God, we might not always like what we get. That's because Gray is a philosophical maverick, a pricker of bubbles, a deflater of balloons, a true iconoclast for whom our chief competing accounts of existence – the religious and the humanist – are both fatally flawed. With disastrous consequences.

Gray's Anatomy (not a great title: Gray's Autopsy would be more appropriate) is a collection of 30 of the British thinker's essays over the past 30 years, on topics ranging from the death of liberalism, which endeared him to Thatcherites for a time, to his assaults on all things neo – neo-atheism, neo-liberalism, neo-conservatism, even neo-Platonism gets a rap – to his apparent evolution toward a kind of wittily despairing Gaian environmentalism.

But any volte-faces are merely apparent. Gray has consistently stuck to his pessimistic guns: Our faith in progress (moral and social, not technical and scientific) is delusional, as is our belief in human uniqueness and the human ability to command our common fates.

The latter view is fully on display in Straw Dogs: Humans and Other Animals (2003), an acerbic attack on humanism as a secular variant of the religious ideologies it displaces and, even more, on our destructive relationship with the natural world. Gray

Born Believers

How your brain creates God

WHILE many institutions collapsed during the Great Depression that began in 1929, one kind did rather well. During this leanest of times, the strictest, most authoritarian churches saw a surge in attendance.

This anomaly was documented in the early 1970s, but only now is science beginning to tell us why. It turns out that human beings have a natural inclination for religious belief, especially during hard times. Our brains effortlessly conjure up an imaginary world of spirits, gods and monsters, and the more insecure we feel, the harder it is to resist the pull of this supernatural world. It seems that our minds are finely tuned to believe in gods.

Religious ideas are common to all cultures: like language and music, they seem to be part of what it is to be human. Until recently, science has largely shied away from asking why. "It's not that religion is not important," says Paul Bloom, a psychologist at Yale University, "it's that the taboo nature of the topic has meant there has been little progress."

The origin of religious belief is something of a mystery, but in recent years scientists have started to make suggestions. One leading idea is that religion is an evolutionary adaptation that makes people more likely to survive and pass their genes onto the next generation. In this view, shared religious belief helped our ancestors form tightly knit groups that cooperated in hunting, foraging and childcare, enabling these groups to outcompete others. In this way, the theory goes, religion was selected for by evolution, and eventually permeated every human society.

The religion-as-an-adaptation theory doesn't wash with everybody, however. As anthropologist Scott Atran of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor points out, the benefits of holding such unfounded beliefs are questionable, in terms of evolutionary fitness. "I don't think the idea makes much sense, given the kinds of things you find in religion," he says. A belief in life after death, for example, is hardly compatible with surviving in the here-and-now and propagating your genes. Moreover, if there are adaptive advantages of religion, they do not explain its origin, but simply how it spread.

An alternative being put forward by Atran and others is that religion emerges as a natural by-product of the way the human mind works.

That's not to say that the human brain has a "god module" in the same way that it has a language module that evolved specifically for acquiring language. Rather, some of the unique cognitive capacities that have made us so successful as a species also work together to

The Greening of Jesus

Riding the train down to london last summer, after a two-week fellowship session on science and religion at the University of Cambridge, I noticed an article in the Independent newspaper about a new book which reinforced that notion of an increasingly irreligious Europe. It is true that outward signs of faith—apart from biblical passages emblazoned on London's famed red double-decker buses by jesussaid.org—are difficult to come by.

But I found deeply felt Christianity alive and well in an unlikely setting: the academy's scientific community. To many, this may seem counterintuitive. The evangelical theologian Alister McGrath told us he once believed that "science was the ally of atheism." Yet among our other lecturers at the Templeton-Cambridge program were major figures in science, from cosmologists to biologists to particle physicists, who pronounced themselves believers. Of course, given the interests of the late Sir John Templeton, who endowed the fellowships, in the relationship between science and religion, this should not have been surprising.

Still, these towering figures—Simon Conway Morris, John Polkinghorne, Sir Brian Heap, Sir John Houghton—characterized themselves as evangelicals as well. Polkinghorne, author of Science and Theology, preaches at a Cambridge church on weekends. To be sure, these are evangelicals of a particular sort. By and large, they reject creationism and intelligent design, embracing the concept of "theistic evolution," a God-created, billions-years-old universe. None numbered themselves among any of the apocalyptic American evangelical tribes of arrogant dominionists or fanciful premillennial dispensationalists of the "Left Behind" stripe.

Much of the modern dialogue between science and religion deals with the origin of the universe and the development of life on earth—surrogate discussions over the existence of God and the divine role in life. In my relatively brief time at Cambridge, a day did not pass without some mention of Charles Darwin—an alumnus—and Richard Dawkins, the best-selling Oxford atheist. Yet to me, these exchanges have become tiresome, repetitive, and unenlightening.

There have been similar debates among scientists of faith over the morality of stem cell research and end-of-life issues. But a more recent (and intriguing, to me) subset of the science and religion dialogue has emerged among evangelical scientists over climate change. Books arguing the religious case for curbing global warming seem to appear every week with titles like A New Climate for Theology: God, the World, and Global Warming and Jesus Brand Spirituality: He Wants His Religion Back, which asks, "Was Jesus Green?" In A Moral Climate: The Ethics of Global Warming, Michael Northcott asserts that "Christ is present among those suffering already from climate change."

Pass on the Pie — and Heavenly Guilt

Weight loss is hard enough without the feeling that the Almighty is on your back, too.

'Tis the season for family, faith, fellowship — and fat.

As families gather around buffet tables smothered with food on Thanksgiving, religious diet groups caution us God might not approve of that second piece of pie. Yes, that's right. The omnipresent world of wonder diets and slim-down regimes now has a foothold in the world of the omnipotent.

Faith-based weight loss groups have been a quietly growing presence for more than three decades. Organizations such as First Place 4 Health, a Texas-based group with chapters in more than 12,000 churches nationwide, and the Weigh Down Workshop,which offers in-person and online Bible-based weight-loss plans, boast that participants have lost the pounds (and kept them off) by placing more faith in God, and less in Ben & Jerry's.

Previously the realm of fundamentalists, bringing a higher power into dieting has gone mainstream. Today, it's not only Christians who see fat as a spiritual issue. According to Buddhist teachings — the latest religion to join the fray of pop faith-based dieting — it's all about moderation and mindfulness.

In a country in which two-thirds of Americans are overweight and nearly a third are obese, it's no surprise that in addition to tapping Jenny Craig or Robert Atkins, people are turning to the real Big Guy. The pounds are piling up, and shedding them is fraught with problems: Approximately half of women and one-third of men in the U.S. are on a diet at any given moment, and within a year, most people regain two-thirds of their lost weight.

Enter religion — the ultimate trump card of many behavior modification programs. For a believer, fear of offending your creator is a powerful force in overcoming the urge to make the shortsighted choice of a burger and fries instead of that leafy salad with light dressing. To underscore the consequences of overeating, the Weigh Down Workshop — one of the most hard-line Christian diet groups — tells participants that God will destroy those who abuse their bodies by overeating. Our bodies are God's temples and, quoting

Why Humans are so Quick to Take Offense

And what that means for the presidential campaign

"No man lives without jostling and being jostled; in all ways he has to elbow himself through the world, giving and receiving offense." —Thomas Carlyle

Rarely has it been thought that the way to show you deserve to be the most powerful person on earth is to demonstrate you're also the touchiest. This presidential campaign has been an offense fest. From the indignation over a fashion writer's observation about Hillary Clinton's cleavage, to the outraged response to the infamous Obama New Yorker cover, to the histrionics over "lipstick on a pig," taking offense has been a political leitmotif. Slate's John Dickerson observed that umbrage is this year's hottest campaign tactic. And we can assume it will reach an operatic crescendo in these final weeks before Election Day.

Feeling affronted has global implications: Islamic organizations and countries seek to ban speech anywhere they decide is insulting to Islam, asserting that a perceived insult can justify a deadly response.

Study the topic of "taking offense" and you realize people are like tuning forks, ready to vibrate with indignation

It's often the pettiest–seeming things that drive people mad. Or worse. Jostling our way through the world can have violent consequences. A significant percentage of murders occur between acquaintances with the flash point being a trivial insult. Sometimes it seems we live in a culture devoted to retribution on behalf of the thin–skinned –just think of university speech codes. Comedian Larry David even celebrates his skill at giving and taking offense on his television show Curb Your Enthusiasm.

Feeling affronted has global implications: Islamic organizations and countries seek to ban speech anywhere they decide is insulting to

Teachers Show Paths to Releasing the Pain

In an upstairs classroom at Stanford University, 35 men and women from the surrounding community silently focus on their breathing, learning the rudimentary steps of meditation as part of an evening continuing-education class on forgiveness.

Fred Luskin, co-founder of the Stanford Forgiveness Project in Palo Alto, has abandoned the research laboratory for another calling. Instead of studying the effects of forgiveness, Luskin now devotes much of his time to teaching people how to forgive. He works in classrooms and businesses, nationally and internationally.

It is a new frontier for a new science: how to actually teach forgiveness. Don't look for a national curriculum anytime soon. Even in the growing library of self-help books, there is a wide array of approaches. Most settle on a process generally ranging from acknowledging the hurt, trying to understand it, perhaps feeling some compassion and then letting go and moving on. Some experts suggest journaling throughout the process; many suggest a group setting or one-to-one coaching to work through it.

Alex Wanted a Cracker, but Did He Want One?

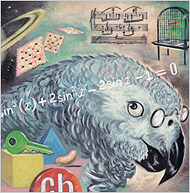

In "Oryx and Crake," Margaret Atwood’s novel about humanity’s final days on earth, a boy named Jimmy becomes obsessed with Alex, an African gray parrot with extraordinary cognitive and linguistic skills. Hiding out in the library, Jimmy watches historical TV documentaries in which the bird deftly distinguishes between blue triangles and yellow squares and invents a perfect new word for almond: cork-nut.

But what Jimmy finds most endearing is Alex’s bad attitude. As bored with the experiments as Jimmy is with school, the parrot would abruptly squawk, "I’m going away now," then refuse to cooperate further.

Except for the part about Jimmy and the imminent apocalypse (still, fingers crossed, a few decades away), all of the above is true. Until he was found dead 10 days ago in his cage at a Brandeis University psych lab, Alex was the subject of 30 years of experiments challenging the most basic assumptions about animal intelligence.

He is survived by his trainer, Irene Pepperberg, a prominent comparative psychologist, and a scientific community divided over whether creatures other than human are more than automatons, enjoying some kind of inner life.

Skeptics have long dismissed Dr. Pepperberg’s successes with Alex as a subtle form of conditioning — no deeper philosophically than teaching a pigeon to peck at a moving spot by bribing it with grain. But the radical behaviorists once said the same thing about people: that what we take for thinking, hoping, even theorizing, is all just stimulus and response.

The Future of Free Will

…each in the cell of himself is almost convinced of his freedom

W.H. Auden, "In Memory of W.B. Yeats"

Do we have free will or not?

A huge question, not to be dismissed. There’s a reason people have worried it so. Our default belief that we are not compelled in our choices, that we are freely responsible for our lives—this belief is central to our sense of self, of the universe, our sense (if we have one) of the purpose of life.

Experiments in neuroscience seem (to some) to threaten all that. And a recent surge of books and articles has frothed the waters. Most visible, perhaps, was New York Times columnist Dennis Overbye’s column in January titled "Free Will: Now You Have It, Now You Don’t". Overbye largely accepts that free will—at least, as it’s often and traditionally defined—is an illusion. An invigorating and necessary debate.

Will free will survive? As we forge into the future and encounter more and more new, hard dilemmas, what we think of human choice and responsibility could affect public policy. Suppose it’s determined we really are not in control. That might change our notions of justice, human rights, reward and punishment. And much else.

Alcohol and Spirituality

How far can spirituality help alcoholics stay sober? In Health Check this week Tracey Logan looks at two non-medical approaches which use spiritual growth to combat alcoholism.

Alcoholics Anonymous is the world's biggest self-help group with meetings in 85 different countries.

Research has shown that it helps more people than conventional treatments and counselling.

It was originally inspired by a form of evangelical Christianity in 1930s America, and its 12-step programme emphasises a God or Higher Power, as well as taking responsibility and helping others.

But AA is very flexible, and its Higher Power isn't fixed, which means the group has flourished among non-Christians and atheists.

Vipassana

In India in 1975 Vipassana, or mindfulness meditation was introduced into a prison in Jaipur. This 10 day intensive meditation course helps people to understand what's happening in their bodies; to accept their cravings, but not to act on them. It's now used in many of the country's jails, including Tihar in Delhi.

Scientists in the US have been studying the effectiveness of Vipassana to help prisoners who are dependent on drugs and alcohol, and have shown it can be used to help people give up alcohol, or cut back on their drinking.

listen now or download mp3 audio, 26.5 minutes, ~6.4 MB

Sketchy Species

Tiny acts, biiiiig consequences

Chance is one thing, necessity another. That’s what they say.

Right?

Chance is what happens for no reason. It just happens to happen. It’s happenstance. Coincidence.

Necessity happens for a reason. It’s cause and effect. It’s consequence.

But what if these distinctions really don’t hold up?

What if chance and necessity aren’t that different? What if they are so intimately knotted we can’t undo them?

What if—yikes—what if they’re just about the same thing?

When I look at my children, all these questions come bubbling up. I think: How’d they get here? It seems impossible, a miracle. But I know the story, and I start retelling it in my head: My wife and I met… but first her parents and my parents had to meet… and their parents…

Many of the things we think are coincidences aren’t that coincidental. My friend and favorite mathematician, John Allen Paulos of Temple University has written this great book called Innumeracy, in which he tells us that many of the things we think are just amazing coincidences aren’t all that.

If there are 23 people in a room, chosen from all the world’s people absolutely at random, what is the probability that two of them have the same birthday? One chance in two. It’s not an amazing coincidence but actually pretty likely. How

Fundamentalists Are Just Like Us

Scott Atran knows a thing or two about fundamentalists, and as far as he's concerned, they are nice people. "I certainly find very little hatred; they act out of love," he says. "These people are very compassionate." Atran, who studies group dynamics at the University of Michigan, is talking about suicide bombers, extremists by anyone's standards and not representative of fundamentalist ideology in general (New Scientist, 23 July, page 18). But surprisingly, much of what Atran has discovered about suicide bombers helps to explain the psychology of all fundamentalist movements.

Ideas about the nature of fundamentalist belief initially drew heavily on work from the 1950s, when psychologists were trying to explain why some people were drawn to authoritarian ideologies such as Nazism. Guided by that research, psychologists focused on individuals, looking for personality traits, modes of thinking and even psychological flaws that might mark fundamentalists out from other people. The conclusion they came to was that there is no real difference between fundamentalists and everybody else. "The fundamentalist mentality is part of human nature," writes Stuart Sim, a cultural theorist at the University of Sunderland in the UK. "All of us are capable of exhibiting this kind of behaviour."

Attention has now turned away from individual psychology to focus on the power of the group. "We evolved to have close and intimate group contacts: we cooperate to compete," says Atran. The psychology of fundamentalism is, literally, more than the sum of its parts; taken individually, fundamentalists are rather unremarkable. "The notion that you might be able to find something in a fundamentalist's brain scan is a non-starter," says John Brooke, a professor of science and religion at the University of Oxford.