Human Beings & the Earth

China Unveils Green Targets

Premier vows to improve energy efficiency and curb pollution and carbon emissions.

Growing environmental costs and energy demands have persuaded China's leaders that the country cannot sustain its breakneck economic growth. In a speech on Saturday at the annual National Party Congress in Beijing, Premier Wen Jiabao announced ambitious five-year goals for increasing energy efficiency and curbing carbon emissions — and a reduced target for economic growth.

In the past five years, China's gross domestic product (GDP) has increased at an average rate of 11.2% a year. The country has reduced its energy intensity — or energy consumption per unit of GDP — by 19.1%, just short of a 20% target set five years ago. Emissions of chemical oxygen demand (a measure of organic pollutants in water) and sulphur dioxide per unit of GDP also dipped by 12.5% and 14.3% respectively, exceeding previous targets of 10%.

The latest five-year plan has lowered the economic-growth target to around 7% a year, and calls for energy intensity to decline by a further 16%. The plan is China's first to include targets for carbon emissions per unit of GDP — to be reduced by 17% — and total energy use, which will be capped at 4 billion tonnes of coal equivalent by 2015, compared with the 3.25 billion tonnes consumed last year (see 'Goals for 2015').

"The targets are very ambitious in global terms," says Antony Froggatt, a climate and environment policy expert at Chatham House, a think tank in London that focuses on international affairs. But because the country's imports of coal, oil and gas are increasing each year, he says, the goals "are crucial for China to become competitive on the global market".

The plans are in line with China's existing aim to reduce carbon intensity by 40–45% from 2005 levels by 2020 (see Nature 462, 550–551; 2009). Froggatt notes, however, that the commitments fall short of what some climate-policy experts regard as a sufficient contribution towards the current international goal of preventing the world's temperature from increasing by 2 °C over the pre-industrial level. "But China is not alone in that," he adds.

To meet its targets, China will scrutinize its entire energy-production chain, from suppliers to transmission and end users, and will inspect industries sector by sector, looking for ways to increase efficiency. The country also aims to raise the proportion of its energy coming from non-fossil fuels — notably, wind energy, hydropower and nuclear power — to 11.4% by 2015. The government hopes that plans to increase spending on research and development to 2.2% of GDP — significantly higher than today — will yield breakthroughs in clean energy.

Environmentalism as Religion

Traditional religion is having a tough time in parts of the world. Majorities in most European countries have told Gallup pollsters in the last few years that religion does not "occupy an important place" in their lives. Across Europe, Judeo-Christian church attendance is down, as is adherence to religious prohibitions such as those against out-of-wedlock births. And while Americans remain, on average, much more devout than Europeans, there are demographic and regional pockets in this country that resemble Europe in their religious beliefs and practices.

The rejection of traditional religion in these quarters has created a vacuum unlikely to go unfilled; human nature seems to demand a search for order and meaning, and nowadays there is no shortage of options on the menu of belief. Some searchers syncretize Judeo-Christian theology with Eastern or New Age spiritualism. Others seek through science the ultimate answers of our origins, or dream of high-tech transcendence by merging with machines — either approach depending not on rationalism alone but on a faith in the goodness of what rationalism can offer.

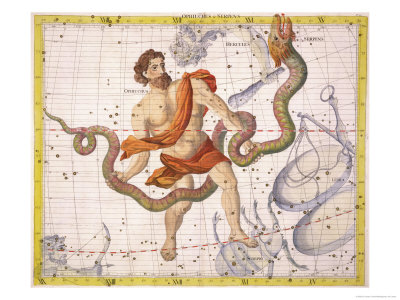

For some individuals and societies, the role of religion seems increasingly to be filled by environmentalism. It has become "the religion of choice for urban atheists," according to Michael Crichton, the late science fiction writer (and climate change skeptic). In a widely quoted 2003 speech, Crichton outlined the ways that environmentalism "remaps" Judeo-Christian beliefs:

"There’s an initial Eden, a paradise, a state of grace and unity with nature, there’s a fall from grace into a state of pollution as a result of eating from the tree of knowledge, and as a result of our actions there is a judgment day coming for us all. We are all energy sinners, doomed to die, unless we seek salvation, which is now called sustainability. Sustainability is salvation in the church of the environment. Just as organic food is its communion, that pesticide-free wafer that the right people with the right beliefs, imbibe."

Rough Seas

Senegal's Threatened Fisheries

In the late afternoon, the Soumbe-dioune Market in Dakar is mostly empty—populated by women rolling peanuts into bags as snacks, a few people brewing up vats of Cafe Touba (a spiced and sugary coffee), and others wiping down their cleaning stations in anticipation of the evening ahead. But when the sun starts to set on the Atlantic Ocean, the market comes alive. The boats pull in, bringing loads of fish in shades of orange, gray, and pink. There’s langouste and mackerel, mussels and barracuda. Massive groupers, bigger than small children, lie on concrete counters, and cases of red mullet and a spread of long, fat eels wait on the sand. Vendors position their products, calling out prices as buyers browse.

The diversity springs from Senegal’s place in the West African Ecoregion, one of the richest and most diverse fishing grounds in the world. The upwelling of cold water along the coast brings nutrients from the depths of the ocean to feed over a thousand of species of fish. Such abundance must have attracted early peoples to the coast, says Papa Gora Ndiaye, a Dakar-based economist and director of the environmental organization ENDA-REPAO. "They had only to take a tree," he says, "cut it and put it into the ocean to take some fish."

By the middle of the twentieth century, people in the government started to realize that the biodiversity of their waters was an asset that could be harnessed, caught, frozen, and airlifted to places in Europe or America or Asia where buyers would pay a lot of money to get it. Mamadou Goudiaby, a researcher from the Office of Maritime Fishing, says that the government hoped to develop the local economy by expanding the fishery and making small-scale fishermen more efficient. "At the beginning, we said the fishery resources were not sufficiently exploited," said Goudiaby. "And the government put programs into place to be able to exploit the fishery."

In the 1970s and 1980s, the government helped small fishermen buy motors so they could go farther out into the ocean. At the same time, the region suffered from a major drought that drove farmers to the coasts, where they thought they could find sure survival and a new career in the sea. And individual fishermen began to prosper. In a small village called Nianing, Mansour Thiaow says that they learned to fish for those foreign markets.

Together Mansour Thiaow and his brothers own six pirogues, small, wooden fishing boats, painted bright blue inside and festooned with the red, yellow, and green Senegalese flags on the outside. The Thiaows fish for everything and anything: giant squid for local hotels, huge mollusks prized as aphrodisiacs by buyers in Japan, and lots and lots of octopus. That’s one of the big money makers.

He says that the fishermen only recently learned how profitable octopus could be. "Gradually, people came and said, ‘Wait, this octopus is commercial.’ So we had to create techniques to attract the octopus and to send it to the European, Asian, or American markets."

Thiaow says that his family has done well. "Before, there wasn’t any electricity at our house. For us, it was candles. Now there is electricity," he says. "There wasn’t water. We went over there," he says gesturing to the ocean. "Now there is a tap at the house. There is a telephone. There are plenty of little things."

Scientists Monitor Fragile Glaciers in Real Time

Using satellite images and email

When cracks appeared this month on one of Greenland’s largest glaciers, the Jakobshavn Isbrae, scientists in Minnesota and Ohio were watching with the help of new tools that come at a crucial time for monitoring such changes around the globe.

It looks like a rift could be opening deep into the glacier, Ian Howat of Ohio State University wrote in a quick email to Paul Morin at the University of Minnesota.

Morin agreed. The satellite image they had just received was something of a red flag, signaling that a large break in the far-away glacier might be imminent. So Morin alerted NASA, a sponsor of their research.

"We sent emails back and forth," Howat said. "While that was taking place...the next satellite image came in — and, boom, here we go — it actually had happened!"

An ice chunk roughly one-eighth the size of Manhattan Island in New York had cracked away from the glacier.

It was the first time scientists had been able to see a break of that magnitude coming and then watch it happen in something very close to real time.

This stepped-up glacier watching is part of a new program at the U of M’s Antarctic Geospatial Information Center, where Morin is the director, and at Byrd Polar Research Center at Ohio State.

It comes at a time when scientists have urgent reasons to closely monitor glaciers and polar regions. Among other reasons, they are watching for events that could lead to rising oceans and other effects related to global warming.

UK Climate Data Were Not Tampered With

Science sound despite researchers' lack of openness, inquiry finds.

The "rigour and honesty" of scientists embroiled in the climate change e-mail affair are "not in doubt" — according to an independent review of the matter released today. However, the scientists have been criticized for a lack of openness that risked "the credibility of UK climate science".

In November 2009, more than 1,000 e-mails and documents were hacked from the Climatic Research Unit (CRU) at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK, and posted on the Internet. They prompted allegations from climate-change sceptics that CRU scientists withheld, concealed and manipulated data in an attempt to boost the case for human-induced climate change. The review, led by Muir Russell, the former vice-chancellor of the University of Glasgow, UK, was charged with investigating the scientists' behaviour. In a 160-page report, the five-person review committee says that it found no evidence of malicious intent, but rather a "consistent pattern of failing to display the proper degree of openness" both among researchers and in the university's leadership in handling the affair.

"They were unhelpful in response to legitimate requests," says Russell, adding that scientists "need to have in the forefront of their minds the importance of the credibility of the knowledge base they are generating and of not losing public trust".

The review has not impressed vocal climate-change critics, such as Andrew Montford who maintains the blog Bishop Hill. "I find the review pretty appalling," he says. "I do not think they have gone deep enough."

Under scrutiny

In exploring allegations that the CRU withheld or tampered with data, the committee scrutinized e-mails concerning the selection of weather-station data in research published in Nature1, led by former CRU director, Phil Jones — who stepped down from his position while the investigation was under way.

To check the paper's conclusion that rising temperatures could not be caused by the local "urban heat island effect" — in which cities tend to be warmer than surrounding rural areas — but should rather be attributed to global climate change, the review panel downloaded the source data directly from publicly accessible sites. "It became very clear, very early on that anyone can get the data...it took us literally minutes to download," says committee-member Peter Clarke, a professor of physics at the University of Edinburgh, UK.

China Outlines Deep-Sea Ambitions

Extra funding promised to help search for natural resources and advance ocean research.

SHANGHAI, CHINA

China is setting its sights on exploring and exploiting the deep sea. Until recently, the country's ocean research focused largely on coastal and offshore waters. But with its breakneck economic development demanding ever more resources, and a growing desire to have more influence in territory disputes and international waters, China is investing heavily in its deep-sea research and exploration programme, experts revealed at a meeting in Shanghai last week.

The move will be reflected in the country's next five-year budget plan, beginning in 2011, with increased funding for oceanography, especially research and development of deep-sea technology, says Baohua Liu, a geophysicist at China's State Oceanic Administration (SOA). Liu will head a newly approved deep-sea centre in Qingdao, Shandong province in eastern China. Construction will begin next year and is expected to take about three years.

The funding boost is largely motivated by China's hunt for oil and minerals, and some scientists worry that research may be sidelined by commercial goals. Others say resource exploration and basic science can coexist. "The strategic shift is extremely far-sighted," says Jian Lin, a marine geologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Massachusetts, one of some 500 participants at the First Conference on Deep-Sea Research and Earth Systems Science. "It is emblematic of the country as a rising world power, on a par with its space programme and polar research."

China's deep-sea ambitions have been bolstered by discoveries from scientists onboard Dayang Yihao, the country's main ocean exploration vessel. They have studied the very slowly spreading Southwest Indian Ridge (SWIR) in the southern Indian Ocean. The ridge separates the African plate to the north from the Antarctic plate to the south and is likely to contain rocks from deep within Earth's mantle.

The Climate Scandal that Never Was

In the grand saga of political battles over climate research, there is no event more pivotal, or more damaging, than what has come to be called "climategate" - the late-2009 theft and exposure of a trove of emails from the Climate Research Unit (CRU) at the University of East Anglia in the UK. Fred Pearce's The Climate Files, based on his 12-part investigative series for The Guardian newspaper in London, is the first book-length attempt to cover the furore.

Some scientists faulted the Guardian series when it appeared, and similar objections apply to this book. Pearce (who is a consultant for New Scientist) writes as though he is covering a real scandal, and takes a "pox on both houses" approach to the scientists who wrote the emails and the climate sceptics who hounded them endlessly - and finally came away with a massive PR victory. But that's far too "balanced" an account.

In truth, climategate was a pseudo-scandal, and the worst that can be said of the scientists is that they wrote some ill-advised things. "I've written some pretty awful emails," admitted Phil Jones, director of the CRU at the time. The scientists also resisted turning over their data when battered by requests for it - requests from climate sceptics who dominate the blogosphere and don't play by the usual rules. But there is nothing very surprising, much less scandalous, about such behaviour. Yes, a "bunker mentality" developed among the scientists; they were "huddling together in the storm," in Pearce's words. But there really was a storm. They were under attack. In this situation, the scientists proved all too human - not frauds, criminals or liars. So why were their hacked emails such big news? Because they were taken out of context and made to appear scandalous. Pearce repeatedly faults the sceptics for such behaviour. Yet he too makes the scientists' private emails the centrepiece of the story. Pearce's investigations don't show any great "smoking gun" offences by the scientists - yet he still finds fault. And who wouldn't, when they can read their private comments in the heat of the battle? (I can't help but wonder what Pearce might think if he had the sceptics' private emails too.)The Data Trail

The Sonoran Desert Reveals Itself to a Passionate Observer

There's something different about the desert this morning. Something's missing. I don't notice it at first, but my companion, who has hiked in the Sonoran Desert every week for nearly 30 years, stops on the trail ahead of me and cocks his head.

"Listen... not a single bird," Dave Bertelsen says. "We should be hearing cactus wrens, canyon wrens, curve-billed thrashers, Phainopepla" -- a crested desert songbird -- "Gambel's quail, Gila woodpeckers. Even in the dead of winter there are birds. This is totally unique. We should be able to just walk along talking and hear birds. To stop and listen hard -- I've never had to do that before."

We're climbing a winding path on a rock-strewn slope in Saguaro National Park, a few miles west of Tucson's city limits. The sun, just four days shy of the winter solstice, will be rising soon. As the world pirouettes out of darkness, a diffuse pink light hides the stars and temporarily softens a hushed landscape in which almost everything seems to be barbed, sharp, or hard. In the still, cool air, a hundred million giant saguaro cacti from here to northern Mexico brace for the dawn, getting a few last gulps of carbon dioxide before sealing their pores and holding their breath all day long to minimize water loss.

Bertelsen doesn't know what to make of the absence of birds on this mid-December morning. For now it's another datum, brand new, puzzling, and disturbing. Besides, we're not on his favorite trail, north of the city in the Santa Catalina Mountains, the one he has walked 1,270 times -- and counting -- since 1981. During that span Bertelsen has amassed an enormous amount of information on the elevation, distribution, and bloom dates of some 600 plant species and subspecies; in 1997 he began keeping equally detailed records of the reptiles and mammals he has encountered during his weekly 10-mile hikes. Last year he added birds. "I now have 195,000 observations," he tells me as we saunter among saguaros, some of them as tall as four-story buildings. "It's a pretty substantial data set."

The decades spent walking this landscape have made the 68-year-old retired probation officer a leading expert on the Sonoran Desert's unique flora and fauna. Bertelsen's mile-by-mile notes of his treks are so precise and voluminous that a team of scientists at the University of Arizona in Tucson is using them to study the effects of global warming here. His records clearly show that about 25 percent of the plant species he has tracked have shifted their ranges to higher, cooler elevations, a response to desert summers that are now close to 2 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than they were 20 years ago. The change is significant, but Bertelsen worries more about stasis.

If Scientists Want to Educate the Public

They should start by listening

Whenever controversies arise that pit scientists against segments of the U.S. public -- the evolution debate, say, or the fight over vaccination -- a predictable dance seems to unfold. One the one hand, the nonscientists appear almost entirely impervious to scientific data that undermine their opinions and prone to arguing back with technical claims that are of dubious merit. In response, the scientists shake their heads and lament that if only the public weren't so ignorant, these kinds of misunderstandings wouldn't occur.

But what if the fault actually lies with both sides?

We've been aware for a long time that Americans don't know much about science. Surveys that measure the public's views on evolution, climate change, the big bang and even the idea that the Earth revolves around the sun yield a huge gap between what science tells us and what the public believes.

But that's not the whole story. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences convened a series of workshops on this topic over the past year and a half, and many of the scientists and other experts who participated concluded that, as much as the public misunderstands science, scientists misunderstand the public. In particular, they often fail to realize that a more scientifically informed public is not necessarily a public that will more frequently side with scientists.

Take climate change. The battle over global warming has raged for more than a decade, with experts still stunned by the willingness of their political opponents to distort scientific conclusions. They conclude, not illogically, that they're dealing with a problem of misinformation or downright ignorance -- one that can be fixed only by setting the record straight.

Bill McKibben on Our Strange New Eaarth

New Point of Inquiry

But according to Bill McKibben, that’s a 1980s view. As McKibben writes in his new book Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet, the increasingly open secret is that global warming happened already. We’ve passed the threshold, and the planet isn’t at all the same. It’s less climatically stable. Its weather is haywire. It has less ice, more drought, higher seas, heavier storms. It even appears different from space.

And that’s just the beginning of the earth-shattering changes in store—a small sampling of what it’s like to trade a familiar planet (Earth) for one that’s new and strange (Eaarth). We’ll survive on this sci-fi world, this terra incognita—but we may not like it very much. And we may have to change some fundamental habits along the way. Eaarth, argues McKibben, is our greatest failure.listen now or download 32min 55sec mp3 file 11.3MB

20,000 Leaks Under the Sea

The insanity of deepwater oil wells

From the comfort of your home or office, through the magic of Web video, you can watch the disaster unfolding on the floor of the Gulf of Mexico. What you're seeing—a leak that has spewed more than 36 million gallons of oil into the Gulf since April 20—is taking place a mile below the water's surface. The temperature there is just above freezing. The pressure is 2,300 pounds per square inch.

No human being could survive there. Everything at the scene—pipes, valves, hydraulic systems—has been remotely installed, through cables, by machines floating on the water's surface. So has the well, which plunges from the sea bed through another 2.5 miles of earth to the oil deposit below.

If nobody's down there, how are you seeing this? Through the eyes of remotely operated vehicles. For six weeks, these undersea drones, built to withstand seawater and crushing weight, have been busy around the leak, trying to shut it down. They've twisted valves, clipped hoses, sprayed dispersant, and poked at the well's unresponsive "blowout preventer." Nothing has stopped the leak. It will go on hemorrhaging oil until an 18,000-foot relief well reaches its source, probably in August.

You can see the spewing oil pipe, but you can't touch it. None of us can. We can't reach it. We've opened a hole in the earth that we can't close.

I'm not talking about the blowout. I'm talking about the well. Every month, we punch more holes in the bottom of the sea. Driven by high gas prices and the depletion of accessible oil fields, drillers are venturing farther offshore and deeper into the earth. Thirty years ago, the record water depth for a functioning rig was less than 5,000 feet. Now it's more than 10,000 feet. One well runs through 4,000 feet of water and another 35,000 feet of earth. Another has been proposed to go through two miles of water and seven miles of earth. Nearly 10 percent of today's oil comes from deepwater wells.

The wells have blowout preventers. But if the preventers fail, as this one did, there's no known way to plug them. Safety regulations generally prohibit diving below 300 feet. The lowest depth attained by a human diver is 2,000 feet, and that was in a suit that makes activity impossible. In deep water, we're at the mercy of ROVs.

Changing Greenland: Viking Weather

As Greenland returns to the warm climate that allowed Vikings to colonize it in the Middle Ages, its isolated and dependent people dream of greener fields and pastures—and also of oil from ice-free waters.

A little north and west of Greenland's stormy southern tip, on a steep hillside above an iceberg-clotted fjord first explored by Erik the Red more than a thousand years ago, sprout some horticultural anomalies: a trim lawn of Kentucky bluegrass, some rhubarb, and a few spruce, poplar, fir, and willow trees. They're in the town of Qaqortoq, 60° 43' north latitude, in Kenneth Høegh's backyard, about 400 miles south of the Arctic Circle.

"We had frost last night," Høegh says as we walk around his yard on a warm July morning, examining his plants while mosquitoes examine us. Qaqortoq's harbor glitters sapphire blue below us in the bright sun. A small iceberg—about the size of a city bus—has drifted within a few feet of the town's dock. Brightly painted clapboard homes, built with wood imported from Europe, freckle the nearly bare granite hills that rise like an amphitheater over the harbor.

A little north and west of Greenland's stormy southern tip, on a steep hillside above an iceberg-clotted fjord first explored by Erik the Red more than a thousand years ago, sprout some horticultural anomalies: a trim lawn of Kentucky bluegrass, some rhubarb, and a few spruce, poplar, fir, and willow trees. They're in the town of Qaqortoq, 60° 43' north latitude, in Kenneth Høegh's backyard, about 400 miles south of the Arctic Circle.

"We had frost last night," Høegh says as we walk around his yard on a warm July morning, examining his plants while mosquitoes examine us. Qaqortoq's harbor glitters sapphire blue below us in the bright sun. A small iceberg—about the size of a city bus—has drifted within a few feet of the town's dock. Brightly painted clapboard homes, built with wood imported from Europe, freckle the nearly bare granite hills that rise like an amphitheater over the harbor.

Høegh, a powerfully built man with reddish blond hair and a trim beard—he could easily be cast as a Viking—is an agronomist and former chief adviser to Greenland's agriculture min istry. His family has lived in Qaqortoq for more than 200 years. Pausing near the edge of the yard, Høegh kneels and peers under a white plas tic sheet that protects some turnips he planted last month.

"Wooo! This is quite incredible!" he says with a broad smile. The turnips' leaves look healthy and green. "I haven't looked at them for three or four weeks; I didn't water the garden at all this year. Just rainfall and melting snow. This is amazing. We can harvest them right now, no problem."

It's a small thing, the early ripening of turnips on a summer morning—but in a country where some 80 percent of the land lies buried beneath an ice sheet up to two miles thick and where some people have never touched a tree, it stands for a large thing. Greenland is warming twice as fast as most of the world. Satellite measurements show that its vast ice sheet, which holds nearly 7 percent of the world's fresh water, is shrinking by about 50 cubic miles each year. The melting ice accelerates the warming—newly exposed ocean and land absorb sunlight that the ice used to reflect into space. If all of Greenland's ice melts in the centuries ahead, sea level will rise by 24 feet, inundating coastlines around the planet.

GM Crop Use Makes Minor Pests Major Problem

Pesticide use rising as Chinese farmers fight insects thriving on transgenic crop.

Growing cotton that has been genetically modified to poison its main pest can lead to a boom in the numbers of other insects, a ten-year study in northern China has found.

In 1997, the Chinese government approved the commercial cultivation of cotton plants genetically modified to produce a toxin from the bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) that is deadly to the bollworm Helicoverpa armigera. Outbreaks of larvae of the cotton bollworm moth in the early 1990s had hit crop yields and profits, and the pesticides used to control the bollworm damaged the environment and caused thousands of deaths from poisoning each year.

More than 4 million hectares of Bt cotton are now grown in China. Since the crop was approved, a team led by Kongming Wu, an entomologist at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Beijing, has monitored pest populations at 38 locations in northern China, covering 3 million hectares of cotton and 26 million hectares of various other crops.

Numbers of mirid bugs (insects of the Miridae family), previously only minor pests in northern China, have increased 12-fold since 1997, they found. "Mirids are now a main pest in the region," says Wu. "Their rise in abundance is associated with the scale of Bt cotton cultivation."

Wu and his colleagues suspect that mirid populations increased because less broad-spectrum pesticide was used following the introduction of Bt cotton. "Mirids are not susceptible to the Bt toxin, so they started to thrive when farmers used less pesticide," says Wu. The study is published in this week's issue of Science.

Altering Food-Crop Genes:

Old issue with new concerns

The global uproar over fiddling with genes in food crops has quieted as millions of people ate products made from genetically engineered corn, soybeans and other plants with no apparent ill effects. But the assessment of the crops’ impacts on the environment and on farmers is far from over.

A comprehensive report released today by the National Research Council shows why it’s important to continue monitoring the technology that overwhelmingly dominates Minnesota’s farm fields. What’s no longer in question is whether farmers would accept the high-tech varieties that first were commercialized in 1996.

Last year, 92 percent of all the soybeans grown in Minnesota carried genes added to help control weeds. Corn was close behind: 88 percent of the Minnesota crop contained genes to help farmers fight insects or weeds or both. "Not since the introduction of hybrid corn seed have we witnessed such a sweeping technological change in U.S. agriculture," said the report compiled by a committee of the Research Council’s Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources. Nationwide, almost half of the land for everything farmers grow is planted to engineered crops — primarily cotton, corn and soybeans. The reasons for the rapid switch to the new technology are many. GE crops take a good share of the guesswork out of farming. They help protect yields, reduce the danger of handling harsh pesticides and save farmers money even though they have to pay a "technology fee" for the GE seed. As for consumers, they have pretty much accepted so-called GMOs with some notable exceptions discussed later in this article. Still, consumers and farmers alike have reason to heed concerns raised in the report.New Nature Conservancy Atlas

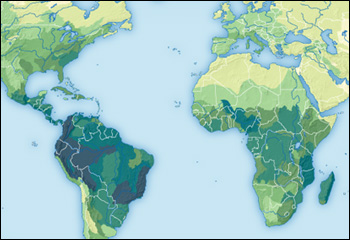

Aims to show the state of the world's ecosystems

What does it take to determine which of the world's 9,800 bird species depend on fresh water for survival? Try devoting two months' worth of evenings and weekends to reading the descriptions of every known avian species, which is what Timothy Boucher did.

"Being a fanatic birder, I decided this could be really fun," recalled Boucher, a senior conservation geographer at the Nature Conservancy who has personally seen and identified 4,257 species of birds in his life. So his "life list," as birders say, covers 43 percent of the bird species that exist.

The result of Boucher's work -- a map showing the wetlands and rivers on which 828 freshwater bird species depend -- is part of the Atlas of Global Conservation, a new publication that shows how nature is faring across the globe.

Environmental researchers evaluate the state of nature in a number of ways -- by listing the most imperiled species, focusing on particular habitats or detailing the pace of human activities that transform the planet. But mapmaking, which provides a visual account of how different ecological regions are faring, provides one of the most easily accessible ways of depicting of the global environment.

The atlas is the work of eight scientists at the Nature Conservancyy who three years ago set out to chart everything from the mangroves in Borneo where proboscis monkeys live to the extent of grasslands on Mongolia's steppes, in order to produce 80 detailed maps.

"The atlas is telling us what's where, what state it's in, what people are doing to it now -- the big threats, and what we can do to turn it around," said senior marine scientist Mark Spalding of the Conservancy.

Cambodia Temple Ruins Spur Wider Question:

Are there time limits to the greatness of a nation?

SIEM REAP, CAMBODIA — "Welcome to the Angelina Jolie temple," our guide said as we climbed stone steps toward Ta Prohm, one of the most beautifully eerie sites in Cambodia's ancient Angkor ruins.

I felt a stab of sadness. Not because the jungle was winning its battle with the 800-year-old temple. Yes, the massive roots of strangler-fig and silk-cotton trees were spectacularly crushing the temple's intricately carved corridors and pillars.

What saddened me was his eagerness to define this amazing icon of his once-great country by deferring to American pop culture. To be sure, he could have done worse than to associate Ta Prohm with the actress-humanitarian who visited here to shoot the 2001 adventure film "Lara Croft: Tomb Raider."

But this ancient wreck of a temple was the work of the mighty Khmer empire that once controlled vast reaches of Southeast Asia. It deserved respect in its own right.

Here and everywhere else in Cambodia, I couldn't stop thinking about how and why great civilizations have failed. The questions had puzzled me before I left Minnesota in February. And they've hounded me since my return.

Was Jared Diamond correct when he said in his book "Collapse" that societies fail because they inadvertently choose to do so?

Losing its mojo?

One reason the question nags is that so many Americans have lost confidence in their own prominence and prosperity. We're surrounded these days by headlines like the one in Newsweek a few months ago: "Is America losing its mojo?"

We still pile up the Nobel prizes (won mostly by American scientists in their 70s, Newsweek noted).

Look deeper, though, and it's clear that America "is like a star that still looks bright in the farthest reaches of the universe but has burned out at the core," Newsweek said.

One of many points it offered in support of that statement came from a study [PDF] last year by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation in Washington. It analyzed 40 countries on various measures of what they were doing to make themselves more innovative in the future. The United States came in dead last.

Lead Recycling Exacts High Price for Health

In the West African nation of Senegal, an informal recycling industry has poisoned children and left a neighborhood severely polluted. Residents caused the contamination by pulling apart car batteries to extract the lead. The government is now cleaning up the site, but many of the children will never be the same. Jori Lewis reports.

*****

MARCO WERMAN: I’m Marco Werman. This is The World. Over the past few years, charitable efforts that focus on children’s health have grown. Philanthropists are donating billions of dollars to the cause, providing medicines and vaccines to protect the world’s poorest kids form infectious diseases like malaria and polio. But there are other threats to the health of children that don’t receive as much attention. Reporter Jori Lewis brings us the story of one such threat. It caused widespread poisoning of children in West Africa, in a poor town outside Dakar, Senegal.

JORI LEWIS: A woman named Seynabou Barry lives in a house by the railroad tracks in a neighborhood called Ngagne Diaw. One day a couple of years ago her toddler son, Mamadou, got sick.

TRANSLATOR (FOR SEYNABOU BARRY, SPEAKING IN WOLOF): It just happened suddenly. He started to throw up and we took him to the hospital.

LEWIS: When he got there, he started to have seizures. And then he died. She said the doctors didn’t know why. But other children in the neighborhood, all infants and toddlers, they were dying, too. Five dead children became ten, and then became fifteen. They were dying almost every week. And so people started to wonder if something was going on in the neighborhood in Ngagne Diaw. Local doctors looked into it. Amadou Diouf is with the Senegalese Health Ministry.

INTERPRETER (FOR AMADOU DIOUF): They investigated and they ruled out malaria. They ruled out epilepsy.

LEWIS: They also ruled out cholera and meningitis. And finally they went to the site, to Ngagne Diaw. And they found the answer. It was lead. There was lead everywhere. Lead in slag piles; in peoples’ homes; in the sand that blew through town. And it was in the children. Many had blood lead levels that indicated severe lead poisoning. The lead mostly came from one source: car batteries. For years a group of local women had been pulling apart old batteries to sell the lead inside. Kine Dior started doing it 20 years ago, when a man showed her how.

- listen… []

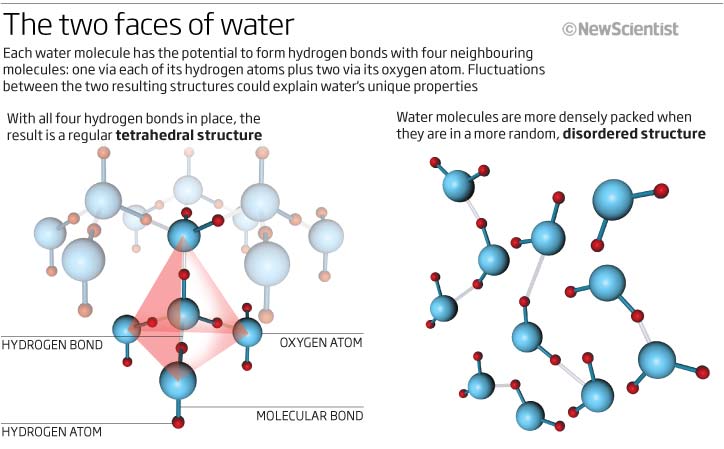

The Strangest Liquid

Why water is so weird

We are confronted by many mysteries, from the nature of dark matter and the origin of the universe to the quest for a theory of everything. These are all puzzles on the grand scale, but you can observe another enduring mystery of the physical world - equally perplexing, if not quite so grand - from the comfort of your kitchen. Simply fill a tall glass with chilled water, throw in an ice cube and leave it to stand.

The fact that the ice cube floats is the first oddity. And the mystery deepens if you take a thermometer and measure the temperature of the water at various depths. At the top, near the ice cube, you'll find it to be around 0 °C, but at the bottom it should be about 4 °C. That's because water is denser at 4°C than it is at any other temperature - another strange trait that sets it apart from other liquids.

Water's odd properties don't stop there (see "Water's mysteries"), and some are vital to life. Because ice is less dense than water, and water is less dense at its freezing point than when it is slightly warmer, it freezes from the top down rather than the bottom up. So even during the ice ages, life continued to thrive on lake floors and in the deep ocean. Water also has an extraordinary capacity to mop up heat, and this helps smooth out climatic changes that could otherwise devastate ecosystems.

Yet despite water's overwhelming importance to life, no single theory had been able to satisfactorily explain its mysterious properties - until now. If we can believe physicists Anders Nilsson at Stanford University, California, and Lars Pettersson of Stockholm University, Sweden, and their colleagues, we could at last be getting to the bottom of many of these anomalies.

Their controversial ideas expand on a theory proposed more than a century ago by Wilhelm Roentgen, the discoverer of X-rays, who claimed that the molecules in liquid water pack together not in just one way, as today's textbooks would have it, but in two fundamentally different ways.

Law and the End of the World

Edwin Cartlidge examines the case of a US lawyer who believes that the courts must step in if required to halt experiments like the Large Hadron Collider.

Before the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) was switched on at CERN in September 2008, stories abounded that the machine might destroy the planet. The fear was that the €6.3bn LHC, which will collide protons together at energies of up to 14 TeV, would be powerful enough to create mini black holes that could consume the Earth – or that it might produce hypothetical "strangelet" particles that could convert the planet into a lump of ultra-dense "strange" matter. These stories certainly left their mark, with people telephoning the Geneva lab in tears imploring researchers not to switch on the accelerator.

Those at CERN never had any doubts that the LHC was safe. Safety reviews published in 2003 and 2008 both concluded that there was no danger that the particle collisions would lead to devastation. These reviews ultimately rested on the simple observation that higher-energy versions of these collisions take place billions of times each second in nature when cosmic rays smash into every object in the universe – bombardments that leave the Earth and all else intact. Indeed, since the collider restarted last November, it has generated record-breaking proton–proton collisions of 2.36 TeV without incident.

Some people, however, remain unconvinced and have tried to halt the LHC through the courts. Plaintiffs have filed lawsuits in Switzerland, Germany, Hawaii and the European Court of Human Rights. However, to date, no action has resulted in a decision on the merits of the case. The Swiss lawsuit was dismissed because CERN straddles the Franco-Swiss border and the lab's treaties with France and Switzerland guarantee it immunity from legal process in both countries. The Hawaii suit was thrown out because the judge handling the claim ruled that US funding and participation in the LHC did not provide the Hawaii court with sufficient jurisdiction under the environmental law invoked by the plaintiffs.

More Heat, Less Light

Good-bye, polar bears. Hello, oil-drenched pelicans. The environmental movement learns the upside of anger.

A couple of months ago, before the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded and began spewing tens of millions of gallons of raw crude into the Gulf of Mexico, Dave Rauschkolb was just some guy with an improbable—some might even call it loopy—dream. A surfer and the owner of three restaurants in Seaside, Florida, Rauschkolb had almost single-handedly organized 10,000 people to gather on 90 Florida beaches and join hands one Saturday in February to protest an offshore-oil-drilling bill that was making its way through the State Legislature. He’d called the event "Hands Across the Sand." In April, after President Obama announced that he would open up vast new expanses of America’s seawaters to offshore drilling, Rauschkolb heard from a woman in Virginia and a man in New Jersey who wanted to hold similar events on their beaches. He offered to help. Then the BP oil spill happened, and Rauschkolb had an idea. What if he took "Hands Across the Sand" national? He envisioned throngs of Americans joining hands on beaches all over the United States and, before long, he wasn’t the only one dreaming big.

When the Deepwater Horizon disaster occurred on April 20, the American environmental movement was already suffering perhaps the lowest morale of its 40-year existence. What had become environmentalists’ primary mission—to convince the world to do something about climate change—was, after a few hopeful years, rapidly slipping away from them. Climate activists were being outmaneuvered by the highly superior political-media operation of their fossil-fuel-industry-funded opponents. The chances of enacting any meaningful climate legislation in the United States—an essential precursor to getting the rest of the world to act—were dropping precipitously. And now, from 50 miles off the Louisiana coast and nearly a mile under the Gulf of Mexico, came this terrible, visceral image of self-inflicted environmental destruction caused by our addiction to oil. "Those of us who have worked on global warming for decades just can’t believe that here we are in a society that really has made almost no change based on the warnings that have come out," John Passacantando, the former executive director of Greenpeace USA, says. "The deep feelings of hurt and failure triggered by the spill are just overwhelming."

Marina Silva the Amazon's Crusader

Taking on the World via the Amazon and Liberation Theology

When international climate negotiators convene next month in Copenhagen, Brazilian politician Marina Silva will serve as the conference's unofficial philosopher-activist. A native Amazonian who grew up in a community of rubber-tappers, Silva worked with murdered Amazonian activist Chico Mendes, won the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize in 1996 and served as Brazil's minister of the environment under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva from 2002 to 2008. She spoke with Washington Post environment reporter Juliet Eilperin during a recent visit to Washington; Stephan Schwartzman of the Environmental Defense Fund translated from the Portuguese. Excerpts:

What inspired you to do environmental work?

It was a combination of things. First, the sensibility I gained from living with the forest, from being born there and taking my sustenance from it until I was 16 years old. Second was my contact with liberation theology, with people like Chico Mendes, a connection that raised social and political consciousness about the actions of the Amazonian rubber-tappers and Indians who were being driven out of their lands because the old rubber estates were being sold into cattle ranches. These encounters made me become engaged with the struggle in defense of the forest. Later, I discovered that this was about "the environment" and the protection of ecosystems. It was an ethical commitment that these natural resources could not be simply destroyed.

How does your Amazon upbringing affect the way you see the issues at stake?

Without doubt, the experience of living in one of the most biologically and culturally diverse regions of the world has affected how I see the world. I see two time frames: forest time and city time. Forest time is slower; things have to be more fully processed; information takes a long time to get there, so people didn't have access to new information. When a new idea arrived, you thought about it, elaborated on it, talked about it for a long time. So this way of thinking, reflecting on and developing ideas, helps me have a sense of the preservation of things, to not make rushed decisions.

We're Doomed Without a Green Religion

Arguments about climate change show up the incoherence of any purely individual morality.

The justification for burning heretics was perfectly simple: dissent threatened the survival of society. Nothing was worse than anarchy. This is a viewpoint most people in the West today find pretty much incomprehensible. It is a self-evident truth to them that morality must be a matter of individual choice. And if you believe that, the arguments around the Tim Nicholson case are very difficult to resolve. If there is a moral imperative to preserve the human race, or as much of it as possible, collective consequences must follow. It is not enough for us to do the right thing. Others must as well. If you don't believe that, then there is no point in agitating for success in Copenhagen.

But if collective consequences follow, others must be forced to do things against their will by our moral imperatives. This is exactly the quality that is supposed to be so very obnoxious about religion.

The idea that morality is and must be a matter of individual choice is taken as axiomatic in these debates. It is thought true in the sense that it is held to describe a fact about the world. Very often the same people who believe this will also believe, and maintain with equal vehemence in other contexts the belief that morals are merely opinions, or at least that there couldn't in the nature of things be moral facts: true or false statements about whether something or someone is good or bad.

This was neatly if not nicely expressed by one of the commenters on Tim Nicholson's article here, who said

You may believe less flying and driving, and more wind farms, and so on to be moral imperatives. I don't. You are entitled to your beliefs, and should not be persecuted for them. But they are just beliefs. You want to argue the politics of how to respond to climate change: great. But you can stop wrapping your proposed solutions up in 'moral imperative' cotton wool.

These are not the only confusions which the Nicholson case raises. Many people who are upset by the court's equating a scientific opinion with a religion belief suppose that science is true and rational, religion is false and irrational, and that this division of the world is itself factual and rational. If this is how the world appears to you, then there is no question that climate change is not a religion. That would mean that it wasn't really happening, and that we were free to ignore it. Both supporters and opponents of environmentalism can often agree both that it might be a religion and that would be a bad thing. This is why, in general, the people who maintain that environmentalism is like a religion are opposed to it; while those in favour deny it is anything like a religion. (A further complication is supplied by right-wing Christians like Daniel Johnson who maintain that religion is a good thing, but environmentalism is a false religion.)

Norman Borlaug: The Man Who Fed the World

My path crossed with 'The Man Who Fed the World' in wheat fields from Mexico to Kenya.

Decades before scientists discovered DNA's double-helix structure, plant breeders were unlocking genetic secrets in the major crops to relieve hunger worldwide.

A giant among those pioneers was Norman Borlaug — the farm kid from Iowa who parlayed his degrees from the University of Minnesota into achievements that earned him the accolades "Father of the Green Revolution," Nobel laureate, winner of the Congressional Gold Medal, and, simply, "Grain Man."

Borlaug died from complications of cancer Saturday night at his home in Dallas, said a spokeswoman for Texas A&M; University, where he was a distinguished professor of international agriculture. He was 95.

"My good friend Norman Borlaug has accomplished more than any other one individual in history in the battle to end world hunger," former President Jimmy Carter said in the foreword to Borlaug's 2006 biography, "The Man Who Fed the World."

I first met Borlaug in a wheat field near Obregon, Mexico, in 1991. I was traveling with a group of science writers who wanted to see first-hand the birthplace of the Green Revolution. It was the home of the breakthroughs that had helped India and Pakistan become self-sufficient in wheat and dramatically boosted yields in China, Latin American, Australia, Europe and the United States.

Borlaug's face lit up when I identified myself as a reporter from Minneapolis. We had dinner together that night, and he spent hours in the field the next day relating his studies in Minnesota to the work that was to save hundreds of millions of people from starvation.

Failed the entrance exam but launched the mission

Borlaug's name marks a building on the University of Minnesota's St. Paul campus where the young man from Cresco, Iowa, began his college education during the Great Depression of the '30s.

I've often wondered whether it was the work ethic of that hardscrabble era or just old-fashioned Norwegian character that gave Borlaug immense pleasure in telling a self-deprecating story about his first months in Minnesota: He failed the University's entrance exam and thus had to start in what then was General College.

'Apostle of Wheat' Borlaug had deep Minnesota roots

Norman Borlaug, who died this weekend at age 95 in Texas, had deep Minnesota roots.

In the final days of a nearly three-year battle with lymphoma, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Norman Borlaug was asked by his daughter if he needed anything.

The 95-year-old responded: "Africa. Africa. I have not finished my mission in Africa," his daughter, Jeanie Borlaug Laube, said Sunday from Dallas.

Norman Borlaug, an Iowa farmboy who graduated from the University of Minnesota, believed food was a moral right. He traveled the world as a scientist and humanitarian, becoming the Green Revolution's "Apostle of Wheat" for the high-yield grain he perfected.

Borlaug, who most recently had been a distinguished professor at Texas A&M; University, died Saturday at his Dallas home with his two children, five grandchildren and six great-grandchildren at his side. He was alert to the end, his daughter said.

Thanks to Borlaug, families in Asia, Latin America and Africa have more to eat. When the National Academy of Sciences awarded him its Public Welfare Medal in 2002, academy President Bruce Alberts said, "Some credit him with saving more human lives than any other person in history.''

Jane Goodall's Animal Planet

In a surprising interview, the famous primatologist talks about her mystical experiences in the jungle and her ever-increasing passion for animal rights and cleaning up the "horrendous mess" of our environment.

Jane Goodall has an iconic status like no other living scientist. For decades, she's lived in the public eye, as we've watched her evolve from curious ingenue to celebrated sage. By now, she's so widely admired that it's easy to forget how she once rattled the cages of the scientific establishment.

At a time when wildlife biologists were taught that animals didn't have minds or personalities, Goodall wrote vivid accounts of David Greybeard, Flo and the other chimpanzees she studied in Tanzania's Gombe Stream. She was the first scientist to observe that chimps not only use tools but make tools. And she was the first to discover that chimpanzees hunt other animals. In three decades of field study, Goodall revolutionized the study of primates and forced people to re-think what it means to be human. As Stephen Jay Gould said, "Jane Goodall's work with chimpanzees represents one of the Western world's greatest scientific achievements."

Goodall's appeal, though, has always stretched beyond her scientific accomplishments. Partly it stems from those old National Geographic shows of the lone white woman out in the bush with these wild apes. The cultural critic Donna Haraway once wrote, "There could be no better story than that of Jane Goodall and the chimpanzees for narrating the healing touch between nature and society," though Haraway went on to say that our fascination with Goodall also played on Western stereotypes about Africa: "It is impossible to picture the entwined hands of a white woman and an African ape

Minnesota Researchers Take on Deadly Fungus Threatening World's Wheat Crop

GREAT RIFT VALLEY, KENYA — A virulent new version of the deadly fungus stem rust is ravaging wheat in Kenya and spreading beyond Africa to threaten one of the world's most important food crops.

The urgency of the threat is not lost on crop scientists in American Midwest. In the 1950s, stem rust destroyed half of the wheat crop in North Dakota and Minnesota and slashed yields elsewhere throughout North America's Great Plains.

That crisis and others like it prompted scientists to create resistant varieties that have filled breadbaskets worldwide ever since.

Now, the killer farmers thought they had defeated 50 years ago is back with a vengeance. It surfaced in East Africa in 1999, jumped the Red Sea to Yemen in 2006 and turned up this year in Iran where it endangers much of Asia.

Scientists are powerless to stop its spread and frustrated in their rush to find resistant plants. The disaster unfolding in Kenya could erupt anywhere the rust spores settle.

Once established, stem rust can explode to crisis proportions within a year under the right weather conditions, said Norman Borlaug, who deployed techniques he had learned at the University of Minnesota to lead the fight against stem rust in the 20th century. He won a Nobel Peace Prize for saving millions from hunger.

"This is a dangerous problem because a good share of the world's area sown to wheat is susceptible to it," Borlaug said. "It has immense destructive potential."

Joseph Atrono knows the full measure of its destructive power. His wheat field, on a ridge overlooking the Rift Valley, is a pathetic tangle of broken stems topped by empty hulls where grain should have formed. Along with the crop went the income Atrono needed to feed his wife and four children.

In the Wheat Fields of Kenya, a Budding Epidemic

Stem Rust, Vanquished by Science Five Decades Ago, Has Returned in a Destructive New Form.

GREAT RIFT VALLEY, Kenya -- A virulent new version of a deadly fungus is ravaging wheat in Kenya's most fertile fields and spreading beyond Africa to threaten one of the world's principal food crops, according to the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization.

Stem rust, a killer that farmers thought they had defeated 50 years ago, surfaced here in 1999, jumped the Red Sea to Yemen in 2006 and turned up in Iran last year. Crop scientists say they are powerless to stop its spread and increasingly frustrated in their efforts to find resistant plants.

Nobel Peace laureate Norman Borlaug, the world's leading authority on the disease, said that once established, stem rust can explode to crisis proportions within a year under certain weather conditions.

"This is a dangerous problem because a good share of the world's area sown to wheat is susceptible to it," Borlaug said. "It has immense destructive potential."

Coming on the heels of grain scarcity and food riots last year, the budding epidemic exposes the fragility of the food supply in poor countries. It is also a reminder of how vulnerable the ever-growing global population is to the pathogens that inevitably surface somewhere on the planet.

The first hint of danger came in an e-mail in 1999 to Ravi Singh, a wheat expert at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Mexico.

A scientist who had trained under Singh was reporting findings from field trials in Uganda. Singh said he could not believe what he saw: Plants that were bred to resist stem rust had succumbed to the fungal parasite.

"It was shocking," Singh said. "We had never seen such susceptibility. . . . The first thing you think is that it probably is not true."

Researchers in South Africa and Minnesota discovered why it was true. In the biological churning that constantly endows old pests with new genetic combinations, stem rust had acquired a frightening ability to punch through the resistance that had guarded wheat for decades.

The Philosopher and the Wolf

Mark Rowlands and his wild lessons in externalism

One day, the eye of the philosopher Mark Rowlands was caught by an advertisement in his local newspaper, the Tuscaloosa News: "Wolf cubs for sale, 96 per cent". Rowlands was eyeballing the father of those cubs just an hour later, the wolf’s yellow eyes on a level with his own, the beast’s enormous paws propping it up against a stable door. This encounter had the opposite effect to that which it would have on most human beings, who fear wolves with a primordial terror. Rowlands purchased one of the cubs and his life changed. Within hours, Brenin had savaged his furniture and destroyed the air conditioning.

When Brenin was alive, he was the centre of Rowlands’s life; each day the creature had to be exercised, fed and settled before the philosopher could embark on anything else. The demand the wolf made on him reminds Rowlands of the myth about St Francis and a wolf that terrorized a village. St Francis made a deal with the wolf, whereby the creature would cease his hostilities if the villagers promised to feed him regularly. The arrangement worked, and firm arrangements are what you need to make with wolves if the relationship is to flourish. Now that Brenin is dead, the philosopher still thinks of his "brother wolf" every day. He misses the relationship that was one of the most formative in his life, and confesses to worrying about Brenin’s bones, now that they lie buried in a lonely spot in the South of France.

In his professional life, Rowlands is known for the idea that consciousness is embedded in the world around us as much as within us.We're Doing God's Science

Why Sir John Houghton Thinks Faith Can Help Save the World

My hiking companion and I have lost our way on this damp late-summer morning. We're on a treeless, mist-shrouded hilltop in Snowdonia National Park, 1,000 feet or so above the Irish Sea along the coast of northern Wales. The bleating of sheep drifts up from the slopes below, muffled by fog that hides the lay of the land. We're trying to reach a village called -- by those able to pronounce its name -- Abergynolwyn, which lies in a nearby valley. But with the murk, we can't find the way down. Sir John Houghton pulls a topographic map and a compass from his backpack. After a few moments of thought he says, "We want to head north. That should take us downhill." So we follow a sheep trail, and a bit later I watch Houghton, who is 76, nimbly hoist himself over a chest-high wire fence.

Charting a path through difficult terrain is nothing new for Houghton, who may be the most important scientist you've never heard of. From 1988 until his semi-retirement in 2002, he was one of the leaders of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a body created by the United Nations 20 years ago to study global warming. As cochairman of the IPCC's scientific working group, Houghton had to coordinate the efforts -- and cope with the egos -- of more than 2,000 scientists from dozens of countries. Against all odds, the IPCC, which could have been a fractious and unwieldy nternational boondoggle, produced a series of authoritative and scientifically rigorous reports firmly establishing the magnitude of the threat posed by climate change. Largely because of the efforts of Houghton's group, the IPCC shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with Al

God Enough

We should see the ceaseless creativity of nature as sacred argues biologist Stuart Kauffman, despite what Richard Dawkins might say.

If this sounds heady, it is. And getting Kauffman to explain his theory of self-organization, "thermodynamic work cycles" and "autocatalysis" to a non-scientist is challenging. But Kauffman is at heart a philosopher who ranges over vast fields of inquiry, from the origins of life to the philosophy of mind. He's a visionary thinker who's not afraid to play with big ideas.

In his recent book, "Reinventing the Sacred," Kauffman has launched an even more audacious project. He seeks to formulate a new

It Isn't About the Trash Can

Picture this: You're staring at the kitchen trash and feel a surge of frustration. You just saw your partner stuff one more thing into the already overflowing bin without making a move to empty it. Ready to pick a fight, you're about to lash out with an angry indictment of your partner's overall worth as a human being. Then you stop.

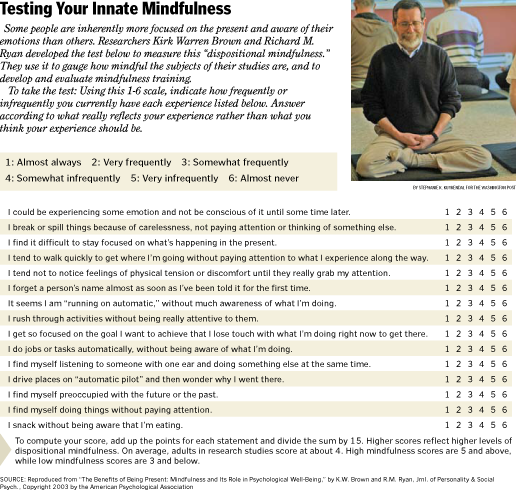

You've been taking classes in something called mindfulness, so you take a deep breath and step back. You identify and feel your emotions, and then let them pass. You find the real source of your frustration: It's not the trash; it's that you don't feel appreciated around the house. Instead of an opening volley of obscenities, you consider how to resolve the broader issue.

Sound too New Age-y to work in your household? It might be worth a try: Researchers at major universities are exploring the benefits of Buddhist mindfulness techniques to help families increase feelings of closeness and decrease relationship stress -- and the results are promising. Just as the latest Hollywood incarnation of the Incredible Hulk keeps his green-hot anger under control with daily meditations, so are some people learning to manage emotions in their relationships.

In mental health terms, mindfulness is the awareness that emerges from focusing on the present and the ability to perceive -- but not judge -- your own emotions with detachment; it enables you to choose helpful responses to difficult situations rather than reacting out of habit. While Western thought separates religion and science, Buddhists see mindfulness as both a spiritual and psychological force.Mindfulness isn't simply about calming down, and it's certainly not about giving in. It's about recognizing that you're tired as you go home on a crowded Metro train, so that when somebody bumps into you, you decide to say, "Excuse me!" instead of pushing back. It's about picking an effective way to discipline your teenager for staying out until 3 a.m. rather than responding like an angry child

Evangelicals Often Clash over Global Warming

When Orlando-based missionary and author Grady McMurtry talks about science and the Bible today at St. Cloud Church of the Nazarene, one question is bound to come up: How should evangelicals respond to the burning issue of global warming?

Relying as much on his degrees in agriculture and environmental science as on his theological education, McMurtry uses Scripture to argue his case that there is no global warming, no thinning of the Earth's ozone layer.

In lectures devoted entirely to climate change, he argues that what warming there may be is cyclical and natural, not caused by human activity. Christians, he insists, should not pay attention to what he calls "junk science" that argues the contrary, as opposed to his controversial brand of "biblical science."

"Many foundational scientific laws and processes are accurately described in the Bible," says McMurtry, author of Creation: Our Worldview.

Yet McMurtry, 61, may be swimming against the evangelical tide. There is a growing scientific consensus on global warming among researchers in the United States and Great Britain who are as devout in their evangelical Christianity as McMurtry is but who have reached dramatically different conclusions on the cause, effect and remedy for world climate change.

This view resonates with a growing number of evangelical congregations across North America, including Northland, a Church Distributed, in Longwood.

Vanished: A Pueblo Mystery

Perched on a lonesome bluff above the dusty San Pedro River, about 30 miles east of Tucson, the ancient stone ruin archaeologists call the Davis Ranch Site doesn’t seem to fit in. Staring back from the opposite bank, the tumbled walls of Reeve Ruin are just as surprising.

Some 700 years ago, as part of a vast migration, a people called the Anasazi, driven by God knows what, wandered from the north to form settlements like these, stamping the land with their own unique style.

"Salado polychrome," says a visiting archaeologist turning over a shard of broken pottery. Reddish on the outside and patterned black and white on the inside, it stands out from the plainer ware made by the Hohokam, whose territory the wanderers had come to occupy.

These Anasazi newcomers — archaeologists have traced them to the mesas and canyons around Kayenta, Ariz., not far from the Hopi reservation — were distinctive in other ways. They liked to build with stone (the Hohokam used sticks and mud), and their kivas, like those they left in their homeland, are unmistakable: rectangular instead of round, with a stone bench along the inside perimeter, a central hearth and a sipapu, or spirit hole, symbolizing the passage through which the first people emerged from mother earth.

"You could move this up to Hopi and not tell the difference," said John A. Ware, the archaeologist leading the field trip, as he examined a Davis Ranch kiva. Finding it down here is a little like stumbling across a pagoda on the African veldt.

For five days in late February, Dr. Ware, the director of the Amerind Foundation, an archaeological research center in Dragoon, Ariz., was host to 15 colleagues as they confronted the most vexing and persistent question in Southwestern archaeology: Why, in the late 13th century, did thousands of Anasazi abandon Kayenta, Mesa Verde and the other magnificent settlements of the Colorado Plateau and move south into Arizona and New Mexico?

What Presidential Candidates--and the Rest of Us--Can Learn from Chimps

The pundits were wrong, de Waal wrote in the March 1 issue of New Scientist. To claim the considerable power of an alpha female, Clinton needed to present herself as older, as the leader of a large block of other women and as an effective bridge builder. In short, she needed to come off as more of an Indira Gandhi than a Paris Hilton in her campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination.

It was a classic example of de Waal's work over the years to further understanding of human culture and behavior by drawing lessons from apes. His acclaimed books — "Our Inner Ape, The Ape and the Sushi Master" and others — have mesmerized readers with profound insights into power, sex, kindness and violence.

Engaging non-scientists Long recognized as a pre-eminent scientist, de Waal was named in 2007 to Time magazine's list of the 100 men and women whose power, talent, or moral example is transforming the world. But he's given every reason to expect he will deftly engage non-scientists in his lectures. On Comedy Central in January, de Waal mixed clear science with a straight-but-droll delivery. "The only reason we biologists don't call humans apes is to protect the fragile human ego," de Waal told Stephen Colbert on "The Colbert Report." Years ago, protestors confronted de Waal over his human-ape comparisons, but that has subsided, he said in a telephone interview on Wednesday. "There may be creationists out there who hate what I say," he said. "But I never run into them. I think it's because they won't come to my kind of lectures."Petroleum Feeds Patriarchy

Climate change. Pollution. Financial expense.

Our gas-guzzling ways have long been associated with a variety of problems, but disturbing evidence now points to a new dimension of our love affair with petroleum: Oil consumption and high oil prices hurt the political, social and economic development of millions of women in oil-producing nations.

You read that right. The more gas you pump and the higher oil prices get, the more likely you are to harm women's empowerment.

The surprising finding, based on more than four decades of data from 169 countries, provides a novel explanation of why women in Middle Eastern countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates still do not have the right to vote. Oil wealth, not Islam, is the primary reason that these nations have regressive gender policies, said political scientist Michael Ross at the University of California at Los Angeles.

As implausible as the connection between oil wealth and gender rights might seem, Ross's work is based on a widely observed pattern: As oil prices soar to more than $100 a barrel, oil-producing countries get rich atop a tidal wave of foreign currency. The tsunami of cash strengthens their currencies and makes it cheaper for them to buy everything from textiles to cars from other nations, instead of manufacturing such goods at home.

As a result, the economies of oil-producing nations invariably have stunted manufacturing sectors while boosting construction and services sectors. This pattern is now so familiar that it has a name -- the "Dutch Disease" -- following the reshaping of the Dutch economy

Requiem for a River

More than 80 years ago, seven western states hammered out a pact dividing up the water in the Colorado River. Agriculture was king and Las Vegas just a railroad watering stop in the middle of nowhere. Today, after an eight-year drought, the river is in crisis.

Snake Valley, Nevada [Elevation 5,300 feet]

Somewhere on the road between the lonely McMansion where the Mormon polygamist's senior wife lives and the dried-up spring where the wild horses died of thirst, I put my foot in my mouth. "How big is your ranch?" I ask Dean Baker, the lean and weathered owner of much of the land around us.

My question seems innocuous enough, but an embarrassed silence envelops the packed Chevy Suburban in which I'm riding with eight Nevada ranchers.

Before Baker can answer, Hank Vogler, a hefty man with a long, droopy gray mustache, interrupts. "Well, that's a bad question," he says. "That's like me asking you what does your wife look like naked. Your reply should be, 'That's none of your damn business.'"

I realize that I've inadvertently put Baker in the uncomfortable position of being asked to reveal his net worth to a stranger in front of his friends. Later I learn that he recently refused a $20 million offer from a real estate speculator for his 12,000-acre ranch, land that he and his family have worked for more than 50 years. The speculator wasn't interested in Baker's modest home, which stands behind a gas station, or even his land. He wanted the water rights. In the nation's driest state, water is a precious commodity.

On this late April afternoon, Baker has organized what he's calling a water tour to show me and ranchers from some of the neighboring valleys what eight years of drought have done to the local springs and water table. Baker raises cattle, alfalfa, barley, corn, and other crops here in the Snake Valley, about 300 miles northeast of Las Vegas. The valley is one of many in the Great Basin, the vast, arid, sparsely populated 200,000-square-mile plateau that sprawls across nearly all of Nevada and half of Utah. West of us, beyond a plain matted with sagebrush, juniper, and greasewood, the Snake range walls off the horizon, with the snowy peak of 13,000-foot Mount Wheeler lambent against the azure high-desert sky. Due east, in Utah, looms the Confusion range, named for its chaotic geologic strata. North, beyond sight over the curved rim of the planet, barren salt flats spread like a bridal train to the Great Salt Lake.

Our first stop is at Needle Point Spring, across the state line in Utah, the site of what was once a small pond. Six years ago, 12 wild horses were found dead there. The pond, on which they depended, vanished nearly overnight after a nearby rancher tapped it to irrigate some new fields. The only sign that water ever flowed there is some dead, brittle gray grass and an empty cattle trough.

The demand for water here, exacerbated by the growth of Las Vegas, has never been greater. Las Vegas, built in the middle of the Mojave Desert, gets 60,000 new residents-and four inches of rain -- each year. To secure the water it needs to maintain that growth, the city plans to build a $2 billion pipeline to pump groundwater from the valleys of northern Nevada. Baker and his fellow ranchers believe the pipeline will be a disaster, not just for them but for the Great Basin ecosystem, which is one reason we've driven to Needle Point Spring. If a single farmer can suck a spring dry, what will happen when a city of nearly two million starts pumping groundwater here?

The remote Snake Valley is but one of the many fronts in a battle for water rights that will play out in the decades ahead across the entire Southwest. The Brobdingnagian twentieth-century system of dams, reservoirs, tunnels, and canals that made possible the explosive growth of desert metropolises like Las Vegas is overtaxed. An unprecedented drought has depleted Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the huge reservoirs on the Colorado River that supply water to some 25 million people and support a $1.2 trillion regional economy. With the onset of global warming, an already bad situation is likely to get much worse. Some climate scientists suspect that the current drought is not an aberration but the start of a transition to permanently drier conditions in the fastest-growing -- and most arid -- region in North America.

Evangelical Leaders Urge Action on Climate Change

Leith Anderson remembers well his "aha" moment on global warming. It was three years ago, when the pastor of Wooddale Church in Eden Prairie, Minn., treated his wife to a long vacation. "My wife and I took an excursion to Antarctica, and for a period of a few weeks, we heard some of the things that were related to global warning as we visited sites," he recalls. "And it impressed me once more that God's gift of our earth is something we need to be effective stewards of."

And as an evangelical Christian, Anderson says, he believes global warning is also a social justice issue, because, he says, it is the poor who feel the brunt of famine or flooding that may come from climate changes.

"Climate changes in terms of famine, in terms of the inability to grow crops, in terms of the flooding of islands, most affects the poor," he says. "So we here in America probably can do many things to exempt ourselves from the immediate consequences, but the front edge of disaster is most going to affect those who have the least."

Anderson, who leads a mega-church of 5,000 worshippers, is one of 86 evangelical leaders who are challenging the Bush administration on global warming. Their "Evangelical Call to Action" argues that there's no real scientific debate about the dangers of climate change — an assertion that many balk at. The group is calling on the government to act urgently, by, among other things, passing a federal law to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.

Some of the signatories have star power, at least in evangelical circles. Among them are Rick Warren, pastor of Saddleback Community Church and author of the blockbuster book, The Purpose Driven Life; Duane Litfin, president of Wheaton College' David Neff, editor of Christianity Today; and Todd Bassett, national commander of the Salvation Army.

But the names of other evangelical heavyweights are conspicuously absent.

"I don't see James Dobson. Is there a more influential evangelican than James Dobson?" observes Richard Land, the president of the Southern Baptist Convention's Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. "I don't see Chuck Coleson. I don't see Franklin Graham. So these are obviously prominent evangelicans and I — please don't in any way think that I am denigrating anyone who's on this list — but it is not an exhaustive list of evangelical leaders, let's put it that way."