Martin Levin

Martin Levin has been books editor of the Globe and Mail in Toronto since 1996. He started at the Globe writing the Climate of Ideas column. Before that, he was editor of the Jewish Post in Winnipeg, where won the Smolar award for editorial writing three times. He also founded and edited two publications: Innings, a baseball newspaper, and Seniors Today. He has written about music for, among others, the Times Literary Supplement and Toronto Life. He has contributed essays to several anthologies, most recently Great Expectations: Twenty-Four Stories about Childbirth, and is co-author of a play about the world's worst film director.

| Interview |

Scientific Fundamentalism Goes Off the RailsDogmatism obscures the fact that we humans "are truly extraordinary," Marilynne Robinson tells Martin Levin.  Martin Levin: What possessed you to immerse yourself in the roiling waters of the science-religion wars? Marilynne Robinson: I happen to be deeply interested in science and religion, so well disposed toward them both that the idea that they are natural adversaries has always bothered me. And I am fascinated by the idea that civilizations generate a hum of insight, invention, disputation, affirmation and controversy, each one like a great mind engaged with its own preoccupations. So for me, attentiveness to these "wars" is attentiveness to the unfolding of human history. That said, the issues that emerge in any culture can be profound or vacuous, brilliantly articulated or dealt with crudely. Science and religion are both profoundly important to our culture, so the integrity of the conversation around them is important as well. G&M;: What determined your approach? MR: I think of Absence of Mind as a critique of a prevailing curriculum, which is the actual basis for the world view that in the context of this controversy is called "scientific." These new-atheist writers carry forward an elderly tradition of polemic against religion which predates modern science and has always been and still is dependent upon positivist notions of rationalism and of the nature of physical reality. So I approach the subject as a problem in the history of ideas. G&M;: Despite the assault of science on religion, it's only in apparent decline in the West and seems to growing in reach and, indeed, fervour in much of the rest of the world. How do you account for this? MR: Has science in fact assaulted religion? Or is it only that the prestige of science has been appropriated in order to make an argument against religion appear authoritative? Somehow it seems to have been accepted by people on both sides of the question that religion stands or falls on the literal truth of one reading of Genesis I. It could as well be argued, for those who attach importance to such things, that the Genesis account is surprisingly consistent with the Big Bang, with the emergence of life in progressive stages, and with the remarkable phenomenon of speciation. But these questions only seem important because the actual substance of religion, the thought and art that have made it the great germinative force behind civilization, are not consulted by people on either side. |

| Interview |

Atheist with a SoulPhilosopher and novelist Rebecca Goldstein speaks with Martin Levin about God and godlessness, and her new novel

I’m thinking that Cass, who’s called an "atheist with a soul," is the character who most embodies your own views, his disbelief in God combined with a larger respect for the religious impulse.He is. In terms of his life, he’s a little hapless and prone to be taken over by personalities larger than his own. I hope I’m not like that, but in terms of his world views, I am with him. Tell me about Azarya [a six-year-old mathematical genius whose abilities will be sacrificially lost in the Hasidic world in which he lives.I thought of this story at least 15 years ago and just didn’t want to write it because I found it heartbreaking and I knew it would have to be tragic. It was an impossible dilemma I was putting this kid in, and I actually thought I’d have to kill him. I resisted writing this for a very long time, but when I got involved with the New Atheism, I thought I could use it as a platform for the Azarya story. His story is the heart of the novel. Your last book was about Spinoza, and his spirit seems to hover over this one as well.Spinoza is the great demonstrator that there can be deep experience of transcendence and the sublime, and what one could call a spiritual experience that is not about God. It is about being itself. Cass endorses this view and often expresses himself this way. The grounding of morality seems to be an important theme, especially as it emerges in the climactic formal debate between Cass and a professor who’s a believer.One of things I wanted to show was that there’s a fallacy in understanding the grounds of morality, that you don’t need God to be moral, sometimes quite the contrary. In the U.S, religious agendas, especially under the last administration, were being legislated and intruding on things like stem-cell research. You hear people say that the godless must be immoral, since you need God to ground morality. No politician in America can say they don’t believe in God. How could they be moral? What do you see as the future for atheism, since religion seems to be declining only in Western Europe and growing throughout the rest of the world.Europe went through its Enlightenment only following protracted, horrible religious wars, when people were convinced that their earlier certitudes were untrustworthy, and modern science and modern philosophy grew out of this. A large part of the world hasn’t gone through this yet. Europe had to have half of its population wiped out before the voices of reason got listened to. But that took a long time. Can we afford that when we have the kind of weaponry that advances in science have given us? We’re in quite a predicament. These very primitive religious emotions – to see the strength of their gathering is terrifying. |

| Review |

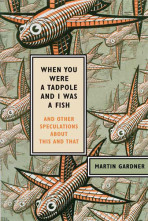

A Science Writer for the AgesAt age 95, Martin Gardner continues to churn out thought-provoking essays and reviews that are aimed squarely at pieties of all kinds.  Martin Gardner is fond of quoting the following from Isaac Newton: "I don't know what I may seem to the world, but as to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me." It's a statement not only of scientific (and thus human) wonder, but of scientific (and thus human) modesty. All of us, even the geniuses, as Newton assuredly was, can at best catch only partial glimmers of "the great ocean of truth." Wading into that ocean is a pursuit that Gardner, though science writer rather than scientist (he usually refers to himself as a journalist), has been engaged in for much of his very long life. And at 95, he shows little sign of abandoning it. Gardner made himself famous as both long-time author of a Scientific American column on mathematical games and diversions and as a thoroughgoing skeptic, author of such works as Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science; published in 1952, it was among the very earliest works to debunk pseudo-science and to scold the popular press for its frequent credulity. My own introduction to Gardner was through another branch of his interests: literature. Gardner virtually invented the now-popular genre of annotated editions of classic works and, relatively early in life, I came upon and hugely enjoyed his editions of "Alice in Wonderland" (The Annotated Alice still sits on my shelves) and Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner". And even though he now resides in an assisted-living home in his native Oklahoma, Gardner continues to churn out essays and reviews, and collect them in books, of which "When You Were a Tadpole and I Was a Fish" is the latest. Here you'll find book reviews and essays in several categories, including Science, Logic, Literature and Religion, all displaying Gardner's trademark erudition, expansiveness and curiosity. Even though he's famously a skeptic, and one of the founders of Skeptical Inquirer magazine, Gardner is no atheist. Rather, as he makes plain in his essay "Why I am Not an Atheist" (a play on Bertrand Russell's book "Why I am Not a Christian"), he is a philosophical theist; that is, one who believes in God but rejects the truth claims of any particular religion. In fact, there are reviews here that debunk the scientific pretensions of Christians, for instance U.S. physicist Frank Tippler ("The Physics of Christianity") and that scourge of the liberals, Anne Coulter. There's a scathing review of Coulter's book "Godless," in which she somehow promotes herself as an (anti-) evolutionary biologist. |

| Article |

Gray, In Black and WhiteJohn Gray's essays are pessimistic, provocative and unsettling. Which is exactly what makes them worth the price of admission.  If John Gray did not exist, it would be necessary, as with Voltaire's God, to invent him. But, as with Voltaire's God, we might not always like what we get. That's because Gray is a philosophical maverick, a pricker of bubbles, a deflater of balloons, a true iconoclast for whom our chief competing accounts of existence – the religious and the humanist – are both fatally flawed. With disastrous consequences. Gray's Anatomy (not a great title: Gray's Autopsy would be more appropriate) is a collection of 30 of the British thinker's essays over the past 30 years, on topics ranging from the death of liberalism, which endeared him to Thatcherites for a time, to his assaults on all things neo – neo-atheism, neo-liberalism, neo-conservatism, even neo-Platonism gets a rap – to his apparent evolution toward a kind of wittily despairing Gaian environmentalism. But any volte-faces are merely apparent. Gray has consistently stuck to his pessimistic guns: Our faith in progress (moral and social, not technical and scientific) is delusional, as is our belief in human uniqueness and the human ability to command our common fates. The latter view is fully on display in Straw Dogs: Humans and Other Animals (2003), an acerbic attack on humanism as a secular variant of the religious ideologies it displaces and, even more, on our destructive relationship with the natural world. Gray |