Ehsan Masood

Ehsan Masood writes on science and the environment in the developing world. A consultant-editor and editorial writer for Nature, he also writes commentary for New Scientist and Prospect magazines as well as a fortnightly column on science, development, and faith for the online magazine OpenDemocracy.Net. His work appears regularly in SciDev.Net, the website operated jointly by the journals Nature and Science. His books include Dry: Life Without Water, written with Daniel Schaffer, and How Do You Know? Reading Ziauddin Sardar on Islam, Science, and Cultural Relations.

| Column |

Scientists of the SubprimeCan biologists avert another banking crisis?  For the past few weeks I've been talking to biologists who are advising the Bank of England on how to reform global finance, as part of a documentary for BBC Radio 4. I've been struck by the ease with which biologists have been able to step outside their research field and move confidently and assertively into another. But what exactly are they up to? One of the causes of the financial crisis – and the haphazard international response to it – was that regulators and governments lacked the tools to understand the banking system as a whole. They knew what individual banks were doing, and they knew that these banks had myriad links to other banks, but they couldn't tell with any certainty what this meant for the banking system overall – until that is, it was much too late. Making sense of the relationship between the individual and the system is one of science's oldest challenges. What might be new to banking is well-studied in biology, for example. This prompted Bob May, ecologist and former government chief scientific adviser, to approach the governor of the Bank of England Mervyn King with an offer of help and advice. Could there be, he wondered, any parallels between banking and ecosystems? Drawing on their knowledge of the study of species and ecosystems, May and several others including Andrew Haldane, the Bank of England's executive director for financial security, constructed a model of the banking system. May has helped pioneer the idea that the most stable ecosystems are those with a diversity of species. Less stable ecosystems have less diversity and a higher degree of connectedness between species. The banking model, which was published last month in the journal Nature, revealed a system that was not only relatively homogeneous – lots of banks with similar characteristics, doing the same things – but also super-connected. As with ecosystems, the model showed that such a system was also vulnerable to shocks. This finding is likely to add weight to a view already gaining ground in the Treasury that there needs to be more diversity in banking and that the same institutions should not be allowed to act as both retail banks and investment banks – in other words, less connectivity. The biologists also applied their knowledge from a different field – infectious disease epidemiology – to see if there are any lessons for finance. They found one that also has implications for regulators. |

| Column |

Science and Islam in the 21st Century"Muslim" does not automatically mean terrorist. Two years after the twin towers fell, a small and disparate movement began that wanted to show the English-speaking world that "Muslim" does not automatically mean terrorist. I was among those who wanted to balance the relentless images of news footage on our TV screens in which men, women and children from Islamic communities are regularly portrayed next to shots of war, violence and terrorism. Some Muslims are in prison for plotting to blow up airliners, and more will follow them. But many more will never see the inside of a police cell and, like all communities, they live both ordinary and extraordinary lives. Recent initiatives from the arts and sciences have attempted to document some of those lives. The Festival of Muslim Cultures, a year-long extravaganza of events across the UK, was aimed at showing how creative innovation is central to the British Islamic landscape. In 2006 the Museum of Science & Industry in Manchester opened its doors to 1001 Inventions, an exhibition showcasing leading-edge scientific discoveries from the Middle Ages. This exhibition has since toured the world and will open at the Science Museum in London next week. The BBC created a landmark TV and radio series called Science and Islam, written and presented by Professor Jim Al-Khalili |

| Column |

Tariq Ramadan's ProjectTariq Ramadan's book "Radical Reform: Islamic Ethics and Liberation" is neither radical nor particularly reformist. But it will be eagerly read from Kuala Lumpur to Keighley. Tariq Ramadan's audiences are famously diverse. Those who hang on the Swiss Islamic reformer's every word include college-going Muslim men and women; policymakers and think-tankers in cities such as London and Washington, even the very authoritarian governments in the middle east from where Ramadan is mostly banned. Each of these constituencies will be delving into Radical Reform: Islamic Ethics and Liberation,a long awaited volume and Ramadan's first scholarly-focused book since his move to St Antony's College, Oxford University. It is ambitious and broad in what it wants to achieve. At times it is highly accessible and at other times technical. Ramadan's tone is much the same as in his previous work. He takes the role of teacher and critic; the reader is cast in the role of student and learner. The book is divided into two parts. The first part takes the reader through the history of reform in Islam's first few centuries. Reform is often seen as a post-colonial project. But the early chapters in his book demonstrate that calls for change within Islam have a much older history. In the later chapters Ramadan sets out his own thinking on how an Islamic ethics could apply to modern innovation. He recognises that the majority of Islamic scholars have little or no training in science or in areas such as bioethics or environmental affairs. He wants them to brush up on advances in modern biology. And he wants them to knock on the doors of ethics committees and make their voices heard alongside other faiths in public debates on science and the environment. He is particularly angry that the states and citizens of Islamic countries have done so little on climate change. Until relatively recently, for example, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait were solidly behind the United States in questioning a human fingerprint in global warming. More surprisingly, however, Ramadan comes down hard on the global Islamic finance industry. This is unexpected because Islamic finance is widely regarded as a rare successful example of the application of Islamic innovation to modern life. Ramadan, however, thinks the industry is not radical enough: he challenges its architects to be bolder and think about whether Islamic ethics in finance has a role, not just to provide interest-free home loans, but in shaping the world's financial architecture. |

| Article |

Islam's Evolutionary LegacyAs we celebrate Darwin, let's not forget the unsung champions of evolution from the Muslim world. Last month, scientists from around the world partied into the small hours on the 200th anniversary of the birth of Darwin. But as we celebrate the work of one of the most influential scientists ever, let's take a moment or two to remember others who contributed ideas in the history of evolutionary thought. Many came from Britain as well as other countries in Europe. Others came from further afield, and their writings are increasingly coming to light thanks to the painstaking work of historians of science, and historians of ideas. One of them is an East African writer based in Baghdad in the 9th century called al-Jahiz. In a book describing the characteristics of animals, he remarked: "Animals engage in a struggle for existence, and for resources, to avoid being eaten, and to breed." He added, "Environmental factors influence organisms to develop new characteristics to ensure survival, thus transforming them into new species. Animals that survive to breed can pass on their successful characteristics to their offspring." Or there's Muhammad al-Nakhshabi, a scholar from 10th century central Asia. He wrote: "While man has sprung from sentient creatures [animals], these have sprung from vegetal beings [plants], and these in turn from combined substances; these from elementary qualities, and these [in turn] from celestial bodies." In their excellent Darwin's Sacred Cause: Race, Slavery and the Quest for Human Origins, Adrian Desmond and James Moore describe |

| Column |

Previous ConvictionsI used to be sure that Islam needed a rational reformation. Yet history has shown me that innovation and freedom have come from faith as much as reason.  Surely Islam needs a reformation? Isn’t literalism in religion an obstacle to open minds; and isn’t the promotion of rationalism the best way to boost the slow pace of science and innovation in the Islamic world? Until a few years ago, I believed that the answer to all these questions was a qualified "yes." Today I am not so sure. This is because I’ve spent the past few years reading my way into the history of science during what is known as the golden age of Islamic civilisation. This is the 700-year period between the 8th and the 16th centuries, when the Muslim faith spread across the world and produced stunning innovations in art, architecture, crafts, medicine, science and technology. When I began my investigations, there was one core idea that I didn’t expect to be challenged on: that blind literalism in religion is essentially a bad thing for science and for society, and that rationalism is always a force for good. Yet, as I immersed myself in the Islamic contributions to astronomy, mathematics, medicine and optics, I discovered something far more complex. Not only was a literal interpretation of religion often a positive influence on the course of science in Islamic times. More astonishingly, a policy of state-sponsored rationalism had led to much suffering, even death; and it had been largely, if unintentionally, responsible for keeping science out of Islamic colleges and universities. Science and innovation tend to be driven by a combination of influences. These include healthcare, defence, politics, business and empire-building as well as the curiosity of the human mind. During the golden era, however, there was an additional driver: a rapidly expanding community of religious believers. Algebra, for example, was developed partly as a tool to simplify complex inheritance formulae. Similarly, spherical trigonometry and mechanical instruments such as the astrolabe were perfected because of obligations to pray daily towards Mecca. The major mosques also doubled up as observatories because they employed timekeepers whose job included having to compute accurate astronomical tables. |

| Article |

New Wave for Islamic ScienceEhsan Masood explores the status of science in the Islamic world today for a new series on BBC Radio 4. He asks whether measures taken to promote science in recent years are having an impact.  In the mid 1990s, I was asked by the science journal Nature to discover the state of science in Pakistan. Like today, Pakistan had become a democracy after more than a decade of military rule. Benazir Bhutto was prime minister. But science then was not a priority. The ministry had no minister and - the nuclear programme aside - the national research budget was less than that of an average UK university. I'd find senior professors sitting behind massive desks in crumbling buildings, with little to do but swat flies and complain how bad everything was. In subsequent years, I've had the dubious honour of witnessing similar scenes in country after country. Scientific research and science spending in today's Muslim nations is on a par with the poorest developing countries - even if you include the wealthy oil-producing states. New wave Take just one statistic and the extent of the problem becomes clear: between 1996 and 2005, scientists from Turkey, among the Islamic world's most productive nations, published 88,000 research papers. That's less than what a single university in America's Ivy League would publish in the same period. Muslim countries spend on average 0.38% of their national wealth on science. The average for a developing country is 0.73%. But now there are real signs of improvement. Iran has always been at the forefront of getting young people to stay in education longer |

| Broadcast |

Science & Islam: The Language of ScienceA BBC documentary examining the great leap in scientific knowledge that took place in the Islamic world between the 8th and 14th centuries. Isaac Newton is, as most will agree, the greatest physicist of all time. At the very least, he is the undisputed father of modern optics, or so we are told at school where our textbooks abound with his famous experiments with lenses and prisms, his study of the nature of light and its reflection, and the refraction and decomposition of light into the colours of the rainbow. Yet, the truth is rather greyer; and I feel it important to point out that, certainly in the field of optics, Newton himself stood on the shoulders of a giant who lived 700 years earlier. For, without doubt, another great physicist, who is worthy of ranking up alongside Newton, is a scientist born in AD 965 in what is now Iraq who went by the name of al-Hassan Ibn al-Haytham. |

| Book |

Science & IslamScience and Islam tells the history of one of the most misunderstood, yet rich and fertile periods in science: the Islamic scientific revolution between 700 and 1500 AD.  Between the 8th and 16th centuries, scholars and researchers working from Samarkand in modern-day Uzbekistan to Cordoba in Spain advanced our knowledge of astronomy, chemistry, engineering, mathematics, medicine and philosophy to new heights. It was Musa al-Khwarizmi, for instance, who developed algebra in 9th century Baghdad, drawing on work by mathematicians in India; al-Jazari, a Turkish engineer of the 13th century whose achievements include the crank, the camshaft, and the reciprocating piston; Abu Ali ibn Sina, whose textbook Canon of Medicine was a standard work in Europe's universities until the 1600s. These scientists were part of a sophisticated culture and civilization that was based on belief in a God – a picture which helps to scotch the myth of the 'Dark Ages' in which scientific advance faltered because of religion.

Science and Islam weaves the story of these scientists and their work into a compelling narrative. He takes the reader on a journey through the Islamic empires of the middle ages, and explores, both the cultural and religious circumstances that made this revolution possible, and Islam's contribution to science in Western Europe. Masood unpacks the debates between scientists, philosophers and theologians on the nature of physical reality and the limits of human reason, and he describes the many reasons for the eventual decline of advanced science and learning in the Arabic-speaking world. Science and Islam is essential reading for anyone keen to explore science's hidden history and its contribution to the making of the modern world.

|

| Article |

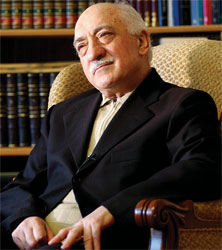

A Modern OttomanThe Turkish cleric Fethullah Gülen, winner of our intellectuals poll, is the modern face of the Sufi Ottoman tradition. At home with globalisation and PR, and fascinated by science, he also influences Turkish politics through links to the ruling  Is it possible to be a true religious believer and at the same time enjoy good relations with people of other faiths or none? Moreover, can you remain open to new ideas and new ways of thinking? Fethullah Gülen, a 67-year-old Turkish Sufi cleric, author and theoretician, has dedicated much of his life to resolving these questions. From his sick bed in exile just outside Philadelphia, he leads a global movement inspired by Sufi ideas. He promotes an open brand of Islamic thought and, like the Iran-born Islamic philosophers Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Abdolkarim Soroush, he is preoccupied with modern science (he publishes an English-language science magazine called the Fountain). But Gülen, unlike these western-trained Iranians, has spent most of his life within the religious and political institutions of Turkey, a Muslim country, albeit a secular one since the foundation of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s republic after the first world war. Unusually for a pious intellectual, he and his movement are at home with technology, markets and multinational business, and especially with modern communications and public relations—which, like a modern televangelist, he uses to attract converts. Like a western celebrity, he carefully manages his public exposure—mostly by restricting interviews to those he can trust. Many of his converts come from Turkey’s aspirational middle class. As religious freedom comes, falteringly, to Turkey, Gülen reassures his followers that they can combine the statist-nationalist beliefs of Atatürk’s republic with a traditional but flexible Islamic faith. He also reconnects the provincial middle class with the Ottoman traditions that had been caricatured as theocratic by Atatürk and his "Kemalist" heirs. Oliver Leaman, a leading scholar of Islamic philosophy, says that Gülen’s ideas are a product of Turkish history, especially the end of the Ottoman and the birth of the republic. He calls Gülen’s approach "Islam-lite." Millions of people inside and outside Turkey have been inspired by Gülen’s more than 60 books and the tapes and videos of his talks. |