Michael Powell

Michael Powell is a native New Yorker and New York bureau chief of the Washington Post. He graduated from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism with a master€™s degree. He has worked at the Burlington Free Press, New York Newsday, The New York Observer and, since 1996, the Washington Post, where he covered former Mayor Marion Barry and wrote on national politics and science and culture for the Style Section. He moved back to New York for the Post just before September 11, 2001, and has since written of terror, politics, the intelligent design battles, and all matter of mayhem large and small.

| Article |

A Knack for Bashing OrthodoxyProfiles in Science: Richard Dawkins OXFORD, England —You walk out of a soft-falling rain into the living room of an Oxford don, with great walls of books, handsome art and, on the far side of the room, graceful windows onto a luxuriant garden. Does this man, arguably the world’s most influential evolutionary biologist, spend most of his time here or in the field? Prof. Richard Dawkins smiles faintly. He did not find fame spending dusty days picking at shale in search of ancient trilobites. Nor has he traipsed the African bush charting the sex life of wildebeests. He gets little charge from such exertions. "My interest in biology was pretty much always on the philosophical side," he says, listing the essential questions that drive him. "Why do we exist, why are we here, what is it all about?" It is in no fashion to diminish Professor Dawkins, a youthful 70, to say that his greatest accomplishment has come as a profoundly original thinker, synthesizer and writer. His epiphanies follow on the heels of long sessions of reading and thought, and a bit of procrastination. He is an elegant stylist with a taste for metaphor. And he has a knack, a predisposition even, for assailing orthodoxy. In his landmark 1976 book, "The Selfish Gene," he looked at evolution through a novel lens: that of a gene. With this, he built on the work of fellow scientists and flipped the prevailing view of evolution and natural selection on its head. He has written a string of best sellers, many detailing his view of evolution as progressing toward greater complexity. (His first children’s book, "The Magic of Reality," appears this fall.) With an intellectual pugilist’s taste for the right cross, he rarely sidesteps debate, least of all with his fellow evolutionary biologists. |

| Column |

Economic Insecurity: The Long ViewEconomix: Explaining the science of everyday life  Americans have climbed a historic peak of pain and uncertainty in the past decade, as the economic insecurity of the American families is greater than at any time on record. One in five Americans, a new report for the Rockefeller Foundation found, has experienced a decline of 25 percent or more in available household income. The typical American experiencing such a plunge will require six to eight years just to climb back to previous levels of income. Measuring the depth and breadth of the recession, and the havoc it has caused for Americans, has become a sort of cottage industry in academia and the nonprofit research world. But what sets apart this Rockefeller examination and several recent studies for other institutions — for instance, this one — is that by taking the longer view, they reveal that problems are deepening with each passing decade. "Economic insecurity has increased over the last quarter-century," states one of the report’s co-authors, Jacob Hacker, a Yale professor. "The level of economic insecurity experienced by Americans was greater than at any time over the past quarter-century." The report, which draws on a variety of Census and Federal Reserve data, notes that in 1985, 12.2 percent of Americans experienced an economic loss sufficient to render them economically insecure. During the recession of the early 2000s, the insecurity rose to 17 percent; today it is 25 percent. |

| Article |

The New PoorDecades of gains vanish for blacks  MEMPHIS -- For two decades, Tyrone Banks was one of many African-Americans who saw his economic prospects brightening in this Mississippi River city. A single father, he worked for FedEx and also as a custodian, built a handsome brick home, had a retirement account and put his eldest daughter through college. Then the Great Recession rolled in like a fog bank. He refinanced his mortgage at a rate that adjusted sharply upward, and afterward he lost one of his jobs. Now Mr. Banks faces bankruptcy and foreclosure. ''I'm going to tell you the deal, plain-spoken: I'm a black man from the projects and I clean toilets and mop up for a living,'' said Mr. Banks, a trim man who looks at least a decade younger than his 50 years. ''I'm proud of what I've accomplished. But my whole life is backfiring.'' Not so long ago, Memphis, a city where a majority of the residents are black, was a symbol of a South where racial history no longer tightly constrained the choices of a rising black working and middle class. Now this city epitomizes something more grim: How rising unemployment and growing foreclosures in the recession have combined to destroy black wealth and income and erase two decades of slow progress. The median income of black homeowners in Memphis rose steadily until five or six years ago. Now it has receded to a level below that of 1990 -- and roughly half that of white Memphis homeowners, according to an analysis conducted by Queens College Sociology Department for The New York Times. Black middle-class neighborhoods are hollowed out, with prices plummeting and homes standing vacant in places like Orange Mound, White Haven and Cordova. As job losses mount -- black unemployment here, mirroring national trends, has risen to 16.9 percent from 9 percent two years ago; it stands at 5.3 percent for whites -- many blacks speak of draining savings and retirement accounts in an effort to hold onto their homes. The overall local foreclosure rate is roughly twice the national average. |

| Article |

2 Churches, Black and White, See Hope Two Methodist churches have stood on the same block on Capitol Hill for a century, one congregation black and the other white, and in between lies the sorry detritus of a nation’s racial history. Again and again these congregations have tried to bridge centuries of misunderstanding, only to falter and drift back. This week they will try again, throwing open their doors together to tend to those celebrating the inauguration of the first black president. "We did not choose but it was chosen for us that we would come together at this moment," said the Rev. Alisa Lasater, the pastor of Capitol Hill United Methodist Church. "If we want to be the heart of our community, we need to learn to see into each others’ heart." In the voice of these churchgoers can be heard the story of race in the nation’s capital and perhaps in the country itself. There are slights and misunderstandings and reconciliations, with miles traveled and more to go. President-elect Barack Obama spoke to such divisions recently in an interview with ABC News, saying he wanted to find that rare church that spanned Washington’s separate worlds, not least of race. "You’ve got one part of Washington, which is a company town, all about government, and is generally pretty prosperous," Mr. Obama said. "And then you’ve got another half of D.C. that is going through enormous challenges. "I want to see if we can bring those two Washington, D.C.’s together." Mr. Obama’s inauguration might offer the nation a new turn, and from that the congregations draw hope. But race’s complications are many, and as these members are reminded daily, they often find themselves speaking from starkly different wells of understanding. The inaugural suggests a nation that, even in unity, experiences history from separate racial vantage points. Once, these two churches were one. In 1829, the white members of Ebenezer Methodist Church cast out their black brethren: You tap your feet too insistently, they said, and sing too loudly. So the blacks walked around the corner and founded Little Ebenezer Church. |

| Article |

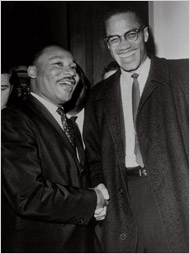

A Fiery Theology Under Fire Black liberation theology was a radical movement born of a competitive time. By the mid-1960s, the horns of Jericho seemed about to sound for the traditional black church in the United States. Martin Luther King Jr. was yielding to Malcolm X. Young black preachers embraced the Nation of Islam and black intellectuals sought warmth in the secular and Marxist-tinged fire of the black power movement. As a young, black and decidedly liberal theologian, James H. Cone saw his faith imperiled. "Christianity was seen as the white man’s religion," he said. "I wanted to say: ‘No! The Christian Gospel is not the white man’s religion. It is a religion of liberation, a religion that says God created all people to be free.’ But I realized that for black people to be free, they must first love their blackness." Dr. Cone, a founding father of black liberation theology, allowed himself a chuckle. "You might say we took our Christianity from Martin and our emphasis on blackness from Malcolm," he said. Black liberation theology was, in a sense, a brilliant flanking maneuver. For a black audience, its theology spoke to the centrality of the slave and segregation experience, arguing that God had a special place in his heart for the black oppressed. These theologians held that liberation should come on earth rather than in the hereafter, and demanded that black pastors speak as prophetic militants, critiquing the nation’s white-run social structures. Black liberation theology "gives special privilege to the oppressed," said Gary Dorrien, a professor of social ethics at Union Theological Seminary in New York. "God is seen as a partisan, liberating force who gives special privilege to the poorest." |

| Article |

Gore Unveils Global-Warming PlanCutting Emissions, Restructuring Industry and Farming Urged  NEW YORK, Sept. 18 -- Former vice president Al Gore laid out his prescription for an ailing and overheated planet Monday, urging a series of steps from freezing carbon dioxide emissions to revamping the auto industry, factories and farms. Gore proposed a Carbon Neutral Mortgage Association ("Connie Mae," to echo the familiar Fannie Mae) devoted to helping homeowners retrofit and build energy-efficient homes. He urged creation of an "electranet," which would let homeowners and business owners buy and sell surplus electricity. "This is not a political issue. This is a moral issue -- it affects the survival of human civilization," Gore said in an hour-long speech at the New York University School of Law. "Put simply, it is wrong to destroy the habitability of our planet and ruin the prospects of every generation that follows ours." Gore was one of the first U.S. politicians to raise an alarm about the dangers of global warming. He produced a critically well-received documentary movie, "An Inconvenient Truth," that chronicles his warnings that Earth is hurtling toward a vastly warmer future. Gore's speech was in part an effort to move beyond jeremiads and put the emphasis on remedies. |

| Article |

The End of EdenJames Lovelock says this time we've pushed the earth too far.  Through a deep and tangled wood lies a glade so lovely and wet and lush as to call to mind a hobbit's sanctuary. A lichen-covered statue rises in a garden of native grasses, and a misting rain drips off a slate roof. At the yard's edge a plump muskrat waddles into the brush. "Hello!" A lean, white-haired gentleman in a blue wool sweater and khakis beckons you inside his whitewashed cottage. We sit beside a stone hearth as his wife, Sandy, an elegant blonde, sets out scones and tea. James Lovelock fixes his mind's eye on what's to come. "It's going too fast," he says softly. "We will burn." Why is that? "Our global furnace is out of control. By 2020, 2025, you will be able to sail a sailboat to the North Pole. The Amazon will become a desert, and the forests of Siberia will burn and release more methane and plagues will return." Sulfurous musings are not Lovelock's characteristic style; he's no Book of Revelation apocalyptic. In his 88th year, he remains one of the world's most inventive scientists, an Englishman of humor and erudition, with an oenophile's taste for delicious controversy. Four decades ago, his discovery that ozone-destroying chemicals were piling up in the atmosphere started the world's governments down a path toward repair. Not long after that, Lovelock proposed the theory known as Gaia, which holds that Earth acts like a living organism, a self-regulating system balanced to allow life to flourish.Biologists dismissed this as heresy, running counter to Darwin's theory of evolution. Today one could reasonably argue that Gaia theory |