Andrew Brown

Andrew Brown is a feature writer for The Guardian and a weekly commentator for its online edition. He also makes documentaries on religious and political subjects for BBC Radio 4. From 1984 to 1986, he was the chief reporter for Spectator magazine and, for the next ten years, the religious affairs correspondent of The Independent. In that latter capacity he won the inaugural Templeton European Religion Writer Award in 1994. His books include The Darwin Wars and In the Beginning Was the Worm.

| Column |

At Least Creationists Have Given it Some ThoughtWould you rather an indifferent or a passionately wrong child in the science classroom? Let's not simply sneer at Darwin deniers.  Yes yes, we're all agreed that evolution is true, and that the biblical (or Qur'anic) accounts of creation are literally false and should not be taught any other way in science classes. This has been the case for at least the last 50 years. Yet studies show that the number of creationists, or at least those who deny or fail to understand the fact of evolution, is very large among the adult population. Last year's Theos study, for example, showed something like 40% of the UK's adult population unclear on the concept. There are also stupefying numbers for the proportion of the British population who think, or who at least will assent to the proposition, that the Earth is around 10,000 years old. This is quite clearly not a problem caused by religious belief. Even if we assume that all Muslims are creationists, and all Baptists, they would only be one in 10 of the self-reported creationists or young Earthers. What we have here is essentially a failure, on a quite staggering scale, of science and maths education. The people who think the Earth is 10,000 years old are essentially counting like the trolls in Terry Pratchett: "one, lots, many". Ten thousand is to them a figure incalculably huge. I don't think this particular innumeracy matters nearly as much as the related inability to calculate that, say 29.3% annual interest on credit card debt is in many ways a much larger and more dangerous number than 10,000 years. But you can't blame either flaw on religious belief. You could perhaps blame it on human nature. There is a lot of good research to show that children are natural creationists, who suppose that there is purpose to the world, and that we have evolved that way. That needn't worry teachers terribly much. A great deal of the world that science reveals is absurdly counter-intuitive and in one sense the whole purpose of education is to lead children away from the "folk beliefs" that they develop naturally. |

| Column |

Why 9/11 Was Good for Religion 9/11 strengthened fundamentalism in every global faith – and in atheism too. But it has also led to backlashes against these doctrines wherever they have appeared. In Islam there have been positive developments. The attacks were repeatedly and clearly condemned by Muslim leaders all over the world. After Pope Benedict XVI's controversial Regensburg speech, the most notable response was the decision of 137 Muslim scholars to sign a declaration outlining what common values they shared with Christians. This "common word" declaration is an example of "hard tolerance" – the increasing practice of making theological differences distinct and then talking about them, rather than trying to conceal them in a syrup of platitudes about love and mysticism. The aim is for priests, imams and rabbis to enter imaginatively into each other's ideologies, rather than simply agreeing. At the same time, the heretical understanding of jihad as the sixth pillar of Islam, which originated in Egyptian circles in the 1980s, spread across south-east Asia. Children in the disputed areas of Pakistan are taught by the Taliban that jihad can compensate for other flaws in a Muslim's life. Among Christians, too, there has been a growth of understanding and interest in Islam, and a simultaneous increase in its demonisation, which this year culminated in Anders Breivik's terrorist attacks in Norway. The mass killer was clearly influenced by a post-9/11 theology that sees Christian Europe under attack from Muslim immigration. Variants of this idea animate political parties in many European countries: the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Italy. For them, Europe's Christian identity has become a sacred value. The same polarised reactions can be seen in secular ideologies. The new atheist movement was started by a group of writers who perceived Islam as an existential threat. "We are at war with Islam," argued one of its leaders, Sam Harris, who also called for the waterboarding of al-Qaida members. Meanwhile The God Delusion author, Richard Dawkins, refers to Islam as the most evil religion in the world. The publication of anti-Muhammad cartoons in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten in 2005, and the furore surrounding it, demonstrated the deliberate use of blasphemy as a weapon in cultural wars. At the same time, secular governments across Europe have made increasing efforts to understand and accommodate religious sensibilities. As welfare states come to seem increasingly expensive, many have turned more and more towards religion to deliver social services. Whatever happens, it appears the idea that religion is doomed and disappearing was buried in the rubble of the twin towers. "9/11 was good for business" says Scott Appleby, professor of history at Notre Dame University. "For many people, we told people that religion is really important and that the secularisation theory, which had been very fashionable, was wrong." |

| Column |

The C of E's Response to the Riots Has Cemented its Role in SocietyYes, there were soundbites, but the Church of England is demonstrating its value as a social body.  Rowan Williams, the archbishop of Canterbury, and Richard Chartres, the bishop of London, have both spoken powerfully in the aftermath of the riots: condemning the criminality, and asking what can be done to rebuild parenting skills and education in the communities affected. They feel that the church is among the biggest parts of society's response to the riots. Williams, speaking in the House of Lords, said: "There is nothing to romanticise and there is nothing to condone in the behaviour that has spread across our streets. This is indeed criminality – criminality pure and simple." It looks as if someone has at last spoken to him sternly about the danger of giving hostages to the Daily Mail. He has remembered to get his condemnation in before coming to all the squishy bits about understanding. He certainly didn't mention forgiveness. When he did talk about understanding the causes of the riots, it was in the context of preventing future ones, rather than excusing anything. For Williams, the cure for further outbreaks could only be found in the long-term and in the reorientation of schools towards teaching virtues rather than skills: "Over the last two decades, our educational philosophy at every level has been more and more dominated by an instrumentalist model; less and less concerned with a building of virtue, character and citizenship – 'civic excellence' as we might say. And a good educational system in a healthy society is one that builds character, that builds virtue. "Character involves … a deepened sense of empathy with others, a deepened sense of our involvement together in a social project in which we all have to participate. "Are we prepared to think not only about discipline in classrooms, but also about the content and ethos of our educational institutions – asking can we once again build a society which takes seriously the task of educating citizens, not consumers, not cogs in an economic system, but citizens." Chartres picked up the same note but more practically: "Those who went on the rampage … seem to lack the restraint and the moral compass which comes from clear teaching about right and wrong communicated through nourishing relationships. The background to the riots is family breakdown and the absence of strong and positive role models." |

| Column |

Anders Breivik is not Christian but anti-IslamNorwegian terrorist Anders Breivik's ideology is fuelled by a loathing of Muslims and 'Marxists', his writing spurred by conspiracy theories.  The Norwegian mass murderer Anders Behring Breivik, who shot dead more than 90 young socialists at their summer camp on Friday after mounting a huge bomb attack on the centre of Oslo, has been described as a fundamentalist Christian. Yet he published enough of his thoughts on the internet to make it clear that even in his saner moments his ideology had nothing to do with Christianity but was based on an atavistic horror of Muslims and a loathing of "Marxists", by which he meant anyone to the left of Genghis Khan. Two huge conspiracy theories form the gearboxes of his writing. The first is that Islam threatens the survival of Europe through what he calls "demographic Jihad". Through a combination of uncontrolled immigration and uncontrolled breeding, the Muslims, who cannot live at peace with their neighbours, are conquering Europe. But these ideas, however crazy, are part of a widespread paranoid ideology that links the European and American far right and even elements of mainstream conservatism in Britain. In an argument on the rightwing Norwegian site Dokument.no, Breivik wrote: "Show me a country where Muslims have lived at peace with non-Muslims without waging Jihad against the Kaffir (dhimmitude, systematic slaughter, or demographic warfare)? Can you please give me ONE single example where Muslims have been successfully assimilated? How many thousands of Europeans must die, how many hundreds of thousands of European women must be raped, millions robbed and bullied before you realise that multiculturalism and Islam cannot work?" He obsessively posted statistics showing the growth of Muslim populations in Lebanon, Kosovo, Kashmir and even Turkey over the centuries in order to demonstrate the same process was under way in Oslo right now, as well as in other European cities. The second is the idea that the elite have sold out to "Marxism", which controls the universities, the mainstream media, and almost all the political parties, and is bent on the destruction of western civilisation. "Europe lost the cold war as early as 1950, at the moment when we allowed Marxists/anti-nationalists to operate freely, without keeping them out of jobs where they could seize power and influence, especially teaching in schools and universities," he wrote. These two grand conspiracies are linked by the "Eurabia" conspiracy theory, which holds that EU bureaucrats have struck a secret deal to hand over Europe to Islam in exchange for oil. |

| Column |

Science is the Only Road to Truth? Don't Be Absurd.Overvaluing science leads to illogicality, as a Nobel prize winner has proved.  By the standards of very clever men who believe some very silly things, Harry Kroto is a quite unremarkable scientist. Unlike some other Nobel prize winners, he is not an enthusiastic Nazi, a Stalinist, a eugenicist, or even a believer in ESP. He did play a prominent, and I think disgraceful part in the agitation to have Michael Reiss sacked from a job at the Royal Society for being a priest. But the video of his speech at the Nobel laureates meeting this year in Lindau, Austria, is something else. Much of it is great stuff about working for love, not money; and about the importance of art, but around eight minutes in he goes off the rails. First there is a slide saying (his emphases): "Science is the only philosophical construct we have to determine TRUTH with any degree of reliability." Think about this for a moment. Is it a scientific statement? No. Can it therefore be relied on as true? No. But formal paradoxes have one advantage well known to logicians, which is that you can use them to prove anything, as Kroto proceeds to demonstrate. Or, as he puts it: "Without evidence, anything goes." Remember, he has just defined truth (or TRUTH) as something that can only be established scientifically. So nothing he says about ethics or intellectual integrity after that need be taken in the least bit seriously. It may be true, but there is no scientific way of knowing this and he doesn't believe there is any other way of knowing anything reliably. Note how this position completely undermines what he then goes on to say – that "the Ethical Purpose of Education must involve teaching our young people how they can decide what they are being told is true" (his caps). Again, this is not a scientific statement, and therefore cannot, on Kroto's terms, be a true one. |

| Column |

Sharia and the Scare StoriesThe arguments about Islam put forward by Michael Nazir-Ali make it difficult to take him seriously.  I was at Hammicks bookshop in London's Fleet Street on Wednesday to hear Michael Nazir-Ali launch a book on sharia law, Sharia in the West. I don't think I will ever be able to take him as seriously again. Politically, of course, his project is entirely serious. It's part of an attempt to take over Christianity in this country. For some rightwing Anglicans, Nazir-Ali is the shadow Archbishop of Canterbury. He has moved out of the official Anglican communion and aligned himself decisively with the conservatives evangelicals of Gafcon, which last week launched its latest attempt to disrupt the Church of England, the "Anglican Mission in England". Charles Raven, one of the leaders of that project, was at the Nazir-Ali book launch, too. Gafcon is normally defined in the media by its campaigns against homosexuality but its members hate much more than that. Reform, the movement's branch in England, is also fundamentally opposed to women priests, and internationally they take a strongly anti-Muslim line. The rich and influential Nigerian Gafcon church sees itself fighting a cold jihad across the centre of the country. Nazir-Ali, who comes from a convert family in Pakistan, has always been hostile to, and suspicious of Islam but in recent years he has increasingly come to talk of it the way that rightwing Americans used to talk about global communism. I have myself argued in favour of Caroline Cox's bill to make plain the limits of sharia law in this country. Sharia can reinforce injustice and some parts of it codify some loathsome attitudes. But sharia arbitration operates by consent; and it will wither in this country if that consent is withdrawn. Talking about Muslims as if they were an alien species makes this far less likely to happen. And that is how many people were talking last night. Nazir-Ali kept talking as if sharia law were an ineluctible consequence of Islam: he spoke of developments in Iran and Pakistan as if Tower Hamlets were next. Another of the animating spirits of the book, the "radical orthodox" theologian John Milbank broke with him in the discussion. "My essays in the book are not at all pro-Islamic," he said, "but I think I am slightly less extreme than the bishop, and I find myself wanting myself not to have this case overstated." |

| Column |

Islamophobia and AntisemitismThere is some violent prejudice against Muslims in Britain today. But is there a more subtle insistence that they're really foreign  The great thing about being in Dubai last week (where I was for a British Council conference on religion and modernity) was being a foreigner once more. It's how I spent much of my childhood, how I grew up, and how I feel most at home; but it brings professional rewards as well as personal pleasures. I was for the first time in my conscious life in an environment where the most important thing about Muslims was not that they were Muslims. It gave me a moment of sudden awareness, like waking in a log cabin without electricity when all the background hum and tension of electric motors that you never normally hear is suddenly audible by its absence. The people I was hanging out, and sometimes drinking, with were Muslim intellectuals whom I know and like in England. They're not in any way discriminated against in this country, as far as I can tell: their lives are not impeded by the kind of people who think that Muslims are a problem to be solved. The kind of crude and open prejudice that flourishes online – and go and look at comments on the Telegraph website, or the videos of Pat Condell, if you want to know what I mean – is very rare in liberal circles, and when we catch ourselves at it, we feel guilty. But there is a more subtle and general sort of prejudice which holds that Condell is not an extremist outcast. Richard Dawkins, for example, has praised Condell, and used to sell his videos on his website, which reminds of the way that Oswald Mosley remained a member in good standing of the English upper classes until the outbreak of the second world war, despite his views on Jews. What I realised in Dubai was that in England today Muslims can't escape being Muslims, any more than Jews in England in the 20s or 30s could escape being Jewish. They can't just be unremarkable, as Jews in England can be now. In Dubai, or neighbouring Sharjah, being a Muslim did not matter in the same way. Obviously, people made a huge amount of fuss about Islam. But when you're in a room full of Muslim academics and students arguing about culture, or censorship, or why there is so little science in the Arab world, the arguments themselves make one thing wholly plain. Neither side is more Muslim than the other. None of the flaws of the Islamic world are essential or intrinsic to it. They may be widespread, and in some cases quite horrible. But they're all cultural and not just religious. |

| Column |

Should We Clone Neanderthals?Given reliable technology, could it ever be ethical to bring our prehistoric relatives back from the dead?  I am at a conference in Dubai on science, religion and modernity, and the best question to come up was "should we clone Neanderthals?" Let's assume the kind of technical progress which would make this look like a possibly ethical thing to do: the failure rate with mammalian cloning has been so high that it really would be rather dodgy to inflict the process on a human being. But for the sake of argument assume a reliable technology and a sufficiency of DNA to work with. Of course, the first difficulty from the strictly utilitarian point of view is that we don't know what the consequences would be. Neanderthal brains were physically different from ours and we have no idea how that impacted their consciousness. We assume they had speech, but this is obviously something that does not fossilise. So it's hard to judge the consequences inflicted on a sentient being when we have no clear idea of what kind of sentience is involved. So a straightforward calculation of the likely consequences can't be done in the way that it can at least be attempted in bioethical questions as they affect homo sapiens. That doesn't mean that religion can provide answers, either. I haven't asked a Roman Catholic but assume that they would apply the same kind of precautionary principle as is applied in the case of abortion: that something which might be a human being should always be given the benefit of the doubt. But other religions, and other forms of Christianity, are not opposed to human cloning. They might not be opposed to cloning Neanderthals. So let's not set it up as a science v religion argument. There will be ethical disagreement, but this will lie between believers as much as between unbelievers. Does it make a difference that this would be an experiment? It's science, which means that we discover things by trial and error. These trials are carefully constructed to ensure that the errors are as instructive as possible, but the outcome can't be known in advance. It's not easy to see how one could be certain of having a complete and viable sequence of Neanderthal DNA when there is nothing to compare it with and only the broad assumption that if the specimen from which it was extracted made it to adulthood it was reasonably healthy. |

| Column |

Social Cohesion Needs Religious BoundariesThe new Prevent strategy shows an old pattern of social organisation is emerging in a new form, around new doctrines.  This is often said to be a country that has outgrown established religion. Yet the two big academic stories of the day show that the problems of social coherence persist that the Church of England was established to solve; and the secularists have no newer or better ideas how to deal with them. Look at the Prevent agenda first. The government's position here is that certain religious or theological beliefs are incompatible with the values on which this country depends; and this is true even if they are compatible with the law. No one suggests that Hizb ut-Tahrir is currently illegal. Few people suggest it should actually be banned. But its beliefs are subversive of the common decencies of society. Islamists, the government now argues, should not be given positions of authority nor government money. This is pretty much the position that Catholics were in 400 years ago: in fact James I's speech after the gunpowder plot was discovered is eerily reminiscent of the Bush/Blair rhetoric after 9/11: "Though religion had engaged the conspirators in so criminal an attempt, yet ought we not to involve all the Roman Catholics in the same guilt, or suppose them equally disposed to commit such enormous barbarities." Or, as we would now say, he condemned extremist Catholics, but was careful to distinguish them from moderates. Considering that the gunpowder plot was an attempt at hugely destructive suicide terrorism, this was a remarkably magnanimous position. But it does show the way in which the established churches of England and Scotland were political and moral constructions necessary for these nations to emerge and function. Laws are simply not enough. Nations need common values and perhaps more than that, common symbols of the sacred. The whole point about a symbol is that it is irrational: people are loyal to it without calculation, and this unreasoned quality is exactly what makes them trustworthy. What's more, symbols, unlike values, can be unequivocally rejected, providing a marker of who is in and who out. Everyone is in favour of motherhood, which is a value, but to venerate the mother of Jesus, who is a symbol, is a profoundly divisive act, and has sometimes come close to treason. It was certainly enough to exclude you from university in England for nearly 300 years. |

| Column |

The Mythical Sam HarrisSam Harris, one of the loudest New Atheists, has built a morality on a home-made myth and calls it scientific.  To open with a nerd joke: religion is like Unix in that those who do not understand it are compelled to reinvent it, badly. Watching Sam Harris at a packed Kensington Town Hall last night, it was obvious that he fits squarely into the American tradition of religious leaders who preach liberation from religion into something they call science. He is Mary Baker Eddy for the 21st century. He was jet-lagged, which may account for some of the incoherence of his position, but he's a very practised performer, and has presumably given this speech hundreds of times before. What he wants to do is to establish that moral facts exist, and that the division between fact and value is not absolute. This is hardly earth-shaking and certainly not original. Nobody was arguing against it, either on the podium or on the floor: when a show of hands was taken at the beginning of the evening, perhaps a dozen out of at least 1,000 hands went up. The difficulty, of course, comes in establishing what moral facts actually are. This Harris assumes is something to be solved by utilitarian calculation. Understandably he skips over any effort to explain or justify this assumption by argument. Instead he uses a myth. Consider, he says, "the worst possible misery for everyone". This is a factual state which surely involves a moral obligation to diminish it. So everything which moves away from that, in the long term, is objectively good. And everything which tends to move the world closer to that state is objectively bad. The obvious retort to this is that our judgements about the way things are tending must involve an element of faith which is something that in other contexts Harris has hoped to escape. But there is a deeper and perhaps less obvious snag. |

| Broadcast |

Mary Midgley: 'There are truths far too big to be conveyed in one go'Philosopher Mary Midgley on morality, mythology and the story of the Selfish Gene  Philosopher Mary Midgley on morality, mythology and the story of the Selfish Gene (interviewed by Andrew Brown and Richard Sprenger) |

| Column |

William James and AgnosticismJust how far will it get us if we resolve never to act beyond what the evidence allows?  Brian Zamulinski provided a long and thoughtful response to William James's case for jumping ahead of the evidence. He argued firstly that "Overbelief" can cause tremendous harm to others, as it did in Stalin's Russia, and secondly that we cannot know in advance how much harm will be caused to others by any belief unjustified by the evidence. It would follow that the only safe course is to avoid altogether believing beyond what the evidence allows. Now the stipulation that overbelief is to be shunned because it can cause harm to others, rather than to the person who believes ahead of the evidence, is a shrewd and subtle attempt to rescue the Clifford position, and to shift it away from James' criticisms. After all, no one who believes in an evolutionary account of religion can seriously suppose that overbelief has in the past caused more harm than "underbelief": waiting to act until the evidence is irresistible. If you believe, as I do, that we have an overdeveloped agency detection system that enables us to apprehend life and purpose where there is none, and that this is a product of evolution, this is pretty irrefutable evidence that waiting to see if that rustle in the grass really was a tiger was more harmful than jumping to conclusions and into the nearest tree. No doubt this was harmful to those more evidence-based hominids who waited to be certain that the rustling was a tiger, but it was good for our ancestors, who jumped. The kind of harm that Zamulinski argues against is much more directly caused by overbelievers. To believe in the triumph of "scientific socialism", no matter what real science said, did kill tens of millions of people. In fact the history of Stalinism provides a paradigm case for evidence-based caution – at least among Western intellectuals. The people we admire in their response to Stalinism are the ones who refused to be taken in: Bertrand Russell, Orwell, Koestler, even Muggeridge, who all modified their initial romantic expectations in the light of experience and stuck to the truth of their disillusionment whatever the subsequent persecutions. |

| Column |

Praying for the PoorThe Micah challenge marks a turn towards social justice from one of the most traditionally conservative kinds of Christianity.  In the light of recent discussion of prayers, it's worth considering that 60 million evangelical Christians around the world will be praying for justice around the world in the hope of abolishing extreme poverty. Leaving God out of it, as they would not wish to do, this is still an impressive and potentially important ritual, because it marks a turn towards social justice from one of the most traditionally conservative kinds of Christianity. In this country, this "Micah challenge" is spearheaded by Joel Edwards, who ran the Evangelical Alliance for 11 years. As such, he had to navigate between extreme fundamentalists and liberal social justice types, something he managed with some skill. But if he's right about this movement, even the most theologically conservative elements are now moving in the direction of greater social responsibility. "Starting with elements of the church who are steeped in personal piety, and or whom anything beyond prayer and personal self-improvement is no go," he says. Moving in to many more Christians who have over the last 10 years accepted that social action is an integral part of our gospel – feeding the poor, clothing the poor, building a hospital in Africa ... But now we are about advocacy for the extreme poor." This is a technical term referring to the 1.2 billion people around the world who live on less than $1.25 a day. They are, of course, found in the countries where evangelical religion of all sorts is thriving most. "We want to bring our moral and infrastructural presence, our biblical convictions, not for our own sakes, but on behalf of the extreme poor." |

| Column |

What Does Prayer Achieve?If praying for someone else does them no good, what is the point of all those words and all that longing?  When I consider my Christian academic friends – people who are smarter, better read and harder working than I am – it's clear that Christianity is a very dangerous profession. Three have daughters who died in their 20s; another has a daughter who is a drug addict. Parents and spouses get Alzheimer's disease when they don't get cancer. I imagine they all prayed for these things not to happen. I know they all still pray. So what is going on here? What is the point of all that prayer? This is hardly a new question. It has been around at least since Job. Nor is there any hope of finding an answer that will convince everyone. But it is possible to tease out a couple of questions. The first is whether intercessory prayer works better than chance. There aren't any reputable studies suggesting that it does, which is, I suppose another example of unanswered prayer, since at least some of these studies must have been commissioned in the hope that they would prove prayer is a worthwhile medical intervention. I wouldn't be surprised, myself, if some forms of prayer worked a bit better than chance. Placebos do, after all. But it would be astonishing if it worked better than placebos. And they are not effective against most devastating diseases. But since placebos don't work on third parties, that rather rules out the idea of praying for someone else's diseases, especially if they are an atheist, still more if they are a stranger. Almost the first study of the effects of intercessory prayer was conducted by Charles Darwin's cousin Francis Galton. This looked at the lifespans of the crowned heads of Victorian Europe, for whom prayers were said by almost all their subjects every week. Their lives were no longer than average. |

| Column |

Creation in a Gulping WormThe exquisite complexity of a tiny and wholly insignificant creature shows Richard Dawkins is right about creationism  Some years ago I wrote a book about a very small, transparent hermaphrodite worm, described by Lewis Wolpert as the most boring organism in existence. The fascinating thing about this nematode, c.elegans, was that it was the best understood and most studied multi-cellular organism in the world, the first to have its genome completely sequenced; yet it still wasn't understood. You would have thought it would be quite impossible for it to do anything unpredicted or impossible to understand. It has no brain, and only 959 cells (for the hermaphrodite). Every single cell in its body is now mapped from the moment of emergence to its death. But until recently, no one knew how it did anything so simple and vital as feed itself. We knew what it ate – bacteria – and how it crushed and digested them; but the worm is a filter feeder, which manages somehow to separate the bacteria from the liquid that they swim in and no one knew exactly how. It was all in the fine timing of the contractions as it swallows, but there are no physical filters in the worm. Whales have whalebone, but worms have no wormbone. Now a kind reader of the book has sent me a paper which he published last year which shows exactly how the filtering was done. Using very high speed video – 1000 frames a second – the team managed to isolate the way that two independent patterns of contraction separate the solid from liquids in a passage smaller than a human hair. I think it is reasonable to say that in purely formal terms there is more complexity and harmony in the stomach of an almost invisible nematode worm than in the most complex and harmonious work of art ever created. The worm is, as I say, quite stupefyingly boring, small and, by animal standards, simple. It lives in literally uncountable billions in earth all over the world. But when you contemplate the effort, the time and the money required to unravel the complexity of even so insignificant a creature, it is easier to understand the futility of creationism. |

| Column |

Is Monogamy the Root of All Equality?An examination of the effects of polygamous marriage suggests it's bad for everyone in society, not just women.  Does polygamy between consenting adults harm anyone else? The question has been raised in Canada, where polygamy has been illegal since the nineteenth century, but the supreme court in British Columbia is going to have to decide whether this law is unconstitutional. Doesn't it infringe the right of adults to arrange their lives by mutual consent? The original law was directed against Mormons, and the present test is also directed against a polygamous fundamentalist Mormon commune. Islam does not seem to have played a major part in the debate there, as it undoubtedly would here. But the interesting thing is that libertarians here line up with the most authoritarian religious groups: most of the motions filed to the court in favour of polygamy come from modern polyamorous groups. However, there has been one brief filed against decriminalising polygamy, and it comes from a most remarkable source: the anthropologist Joe Henrich at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. This has been the source of much of the most interesting and solid scientific research on religion in the last ten years. Henrich himself has an upcoming paper on Why people believe in God but not in Santa Claus, or Zeus. The particular merit of this school is that it refines the ideas of evolutionary psychology to take cultural norms just as seriously, and to look at group level competition, which is mediated by culture, quite as seriously as individual competition within groups. Polygamy is a fascinating test case for this approach because the benefits all accrue to the alpha males who end up with most women, whereas the costs are paid by everyone else, and by society as a whole. In a long affidavit to the court, Henrich considers the social and psychological benefits of monogamous marriage. These aren't widely accepted: using the larget available database of anthropological surveys Henrich concluded that 85% of human societies allow high-status men to have more than one wife. It;s important to notice that this is different from the observation that men (and women) will cheat on each other. That's mating behaviour, which Henrich distinguished from marriage, which is a set of socially accepted and enforced norms and arrangements. In fact he writes that "given our evolved mating psychology, the puzzle is not why societies are polygynous; it's why any society is monogamous, especially one in which males are highly unequal, (like ours)." The answer he gives is that monogamy gives huge advantages to societies which practice it. It arose, like philosophy, among the Greeks, passed through the Romans, and then the Christian church took it over as an ideal and managed over the course of around a thousand years to establish it as the norm in Europe, even for the aristocracy. |

| Column |

Richard Dawkins's Backward Logic over Atheist SchoolingRichard Dawkins's belief that any properly brought up child will naturally be an atheist leads him into absurdity.  Richard Dawkins on Mumsnet came up with a remark to silence all his critics: "What have you read of mine that makes you think I have a skewed agenda?" It certainly left me opening and shutting my mouth like a breathless goldfish. Actually the whole thread is worth reading: it is from here that the story has come forth that he wants to start an atheist school. Whether that will actually happen is another thing. But it is in any case revealing of his reasoning. (There doesn't seem to be a way to link to individual comments on Mumsnet, but all these quotes are cut and pasted from the thread.) He was asked by one commenter: "What would you say to parents of children who attend quite orthodox state-funded schools who are very anxious that their child be educated within that context? I am thinking specifically of the ortho-Jewish schools around my way (north London). I know for a fact a lot of these parents cannot countenance the idea of their child being educated within a non-Jewish school. What do you think they should do?" His response was: "That's a good point. I believe this is putting parental rights above children's rights." It is impossible to read this as meaning anything but that children have a right to be educated as Richard Dawkins thinks fit, but not as their parents do. He alluded several times in the threat to the sufferings of atheist parents forced to send their children to faith schools: "Is it better to stand by one's principles or be hypocritical in order to provide the best option? What a horrible dilemma to be forced into." But apparently this doesn't apply if your principles are religious ones, because then your children have a right to be educated as atheists. Of course, the Dawkins position here is purely a matter of assertion. It's impossible to imagine anything that might qualify as evidence for the view that it is okay for atheists to discriminate against parents who have particular religious beliefs, while it is very wrong for believers to do so. But "evidence", tends to be defined backwards in these polemics – in other words, he starts from the axiom that there is no evidence whatsoever for the existence of God, (implied here in his remark that "Every atheist I know would change their mind in a heartbeat if any evidence appeared in favour of religious belief") and then find meanings for the term that fit this use. This is of course the same trick as defining faith as belief without evidence and then using this definition as proof that faith is irrational. |

| Column |

Times Change at the VaticanA forgotten encyclical on virginity shows just about everything that the Vatican can get wrong.  We've all made terrible mistakes with search and replace, but the Vatican's webmaster has come up with a classic: if you look up Pius XII's 1954 encyclical on Sacred Virginity, as who wouldn't, you will learn in paragraph 3 that: "Right from Apostolic Times New Roman this virtue has been thriving and flourishing in the garden of the Church." Presumably this was the result of a script which was meant to affect only style sheets, and change references to the "Times" font to the more precise "Times New Roman". I would have thought that under the present pontiff they would anyway have changed to some more suitable font, like "Times Unchanging Roman". But in fact the church does change, and nothing could make this clearer than the encyclical itself. It shows us a world which is now gone forever – and good riddance. St. Peter Damian, exhorting priests to perfect continence, asks: "If Our Redeemer so loved the flower of unimpaired modesty that not only was He born from a virginal womb, but was also cared for by a virgin nurse even when He was still an infant crying in the cradle, by whom, I ask, does He wish His body to be handled now that He reigns, limitless, in heaven?" |

| Column |

Myth, Heaven, and GalileoWhat we can see in the stars depends on our instruments and on our expectations. The instruments are easier to improve.  Some months back, I wrote a piece about Galileo's science, and how the discoveries of his telescope ought to have led him to conclude that Copernicus was wrong. This morning I had a letter – an actual posted, folded, paper letter – from Kentucky. It came from Christopher Graney, the science teacher whose work lay behind the Nature article, and contained a copy of his original paper setting out the full reasoning in terms that even high school students and national newspaper journalists can understand. Given the resolution of early telescopes, and the assumption of all early astronomers that what they saw through them were the stars themselves, and not the apparently much larger "Airy disks" produced by diffraction, Galileo's telescope showed that the earth must rotate (so the mediaeval picture was wrong), but could not have gone round the sun, as Copernicus believed. What Galileo should have believed, according to this reconstruction, was the system put forward by Tycho Brahe, which had the earth at the centre, and the moon and sun orbiting us, while all the other planets orbit the sun. This piece was based on a short note in Nature and provoked a fairly lively debate about science and judgement here. It's still complicated, of course. There is a reason why Galileo and Kepler are remembered as geniuses. But two facts are important. The first is that there is no way to decide from the measurements of planetary orbits available in the seventeenth century whether Tycho was right and all the planets orbit the sun except the earth, around which the sun revolves, or whether Copernicus was right and all the planets, including the earth, revolve around the sun. An evidence dalek would have been stuck on the staircase here, because the evidence of planetary observations gave no ground to choose between the two theories. What mattered in making the decision were the observations of the stars. |

| Column |

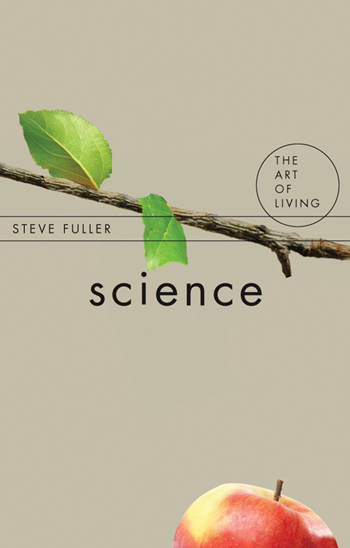

Theology: Natural and UnnaturalIs there any possible defence for "Intelligent Design"? Is there any way for theists to abandon the idea?  Steve Fuller is the sociologist of science notorious for arguing that Intelligent Design was not necessarily a bad research programme even though it was rotten science. In this capacity he appeared as a witness for the defence in the Dover trial in the US, the most recent attempt to smuggle creationism into the public school system there. He has written a new book on science as the heir to religion, which will be published later this spring, and there will be a Question series about this later. Commissioning pieces for this got me thinking about the boundaries of natural theology and how we can classify it. It is an undisputed fact that many great scientists have been driven by Christian faith and the roots of modern science lay in the belief that the scientist was "reading the book of Nature", which was understood to be a revelation of God's purposes and character quite as much as the other Book, the Bible was. This was certainly Newton's motivation, and Faraday's. But it seems also to have been contested from an early stage. Looking back at Wesley's pamphlet on the Lisbon earthquake, which was written much closer to Newton's death than Faraday's, we can see him already arguing against an atheist who believes only in "the fortuitous concourse and agency of blind material causes." So we know that there were materialists to argue against. What there were not, then, were believers in scientific progress, nor anyone who could foresee the enormous advances of the nineteenth century. For Wesley the response to plague was prayer, not bacteriology. The progressive or whiggish account of natural theology would say that in order to find the hidden regularities of nature we needed to believe they were there, and, Christian faith gave scientists the confidence needed to do so. But – this account continues – once the architecture of the universe had been sketched out, the need for an architect receded. The elegant mathematics of the universe that physics revealed became their own justification: Laplace, when asked what God did in his model of the solar system, replied "I have no need for that hypothesis"; later, something similar happened in biology under Darwin's influence. Natural theology had started as a way of understanding God; in the eighteenth century it became a way of proving God's existence, which is something rather different, which turned out to be catastrophic for Christian apologetics, as is shown by the fact that Richard Dawkins works entirely within this tradition: he shows instance after instance of design in the natural world, and then shows that there is no need for a designer, and that if any agency had designed the natural world we see, we couldn't call it wise or loving. But Dawkins, here, is kicking at an open door. Many others have been through it before him. Once you destroy the idea that science can prove the existence of God, or can discover things that only God's existence can explain, the first half of natural theology also looks pointless: why investigate the nature of a non-existent being? |

| Column |

How to Listen to GodAn anthropological study of charismatic Christians reveals a belief system at once childish and sophisticated.  I went last night to a marvellous talk by an American anthropologist who has been studying Californian charismatic Christians. Tanya Luhrmann's enquiry into how these people construct their idea of God will result in a book eventually, but in the meantime her talk on her work with the Vineyard churches was full of insight, sympathy, and deadpan humour. The Vineyard churches are a loose international network of mostly white, mostly middle class, very charismatic churches. They aren't exactly fundamentalist but they see the Holy Spirit everywhere and talk to God every day. They were the source of the "Toronto Blessing" - a craze which swept through the English charismatic network in the 90s where people fell on the floor and made animal noises. Luhrmann is interested in how you get to talk to God like this. After all, most churches for most of history, haven't done anything like that. Her answer is that you need a certain kind of temperament, one which makes you good at make-believe, and then you need to work at it. The personality traits which make it easiest to talk to God are those measured on the Tellegen absorption scale, which she summarises as the ability to focus attention on a non-instrumental subject: in other words, some thought interesting for its own sake, whether or not it is obviously useful. It's the facility you need to construct compelling daydreams. If you have this talent, or temperament, in the first place, these churches will nourish it. By treating God as real, you come to detect his presence more easily; and the God for whom the are searching is one just like another person. "People learn about God by mapping onto Him what they know about persons; then they map back what they suppose about God onto the world around them." All this activity is the subject of tremendous social reinforcement. These are not Sunday only churches. Members can fill their lives with meetings with other members – and with God. "They pay constant attention to what's going on in their minds. They are constantly looking at their thoughts and images. It's a social shaping of what you would imagine to be a private space in their minds. |

| Column |

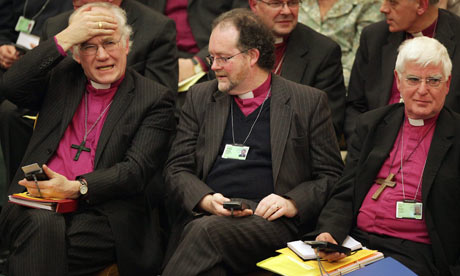

Are Science and Atheism Compatible?Science brings no comfort to to anyone with dogmatic beliefs about world.  The General Synod this morning held a debate on whether science and religion are mutually exclusive, full of ordained scientists arguing that of course they are, and indeed the final vote was 241 to two in favour of the motion. I have failed to establish the identity of the dissident two. Faced with such a consensus I thought it might be fun to flip the question on its back and ask to what extent science is compatible with atheism. Obviously the two are closely linked, in as much as science assumes the falsity, or at least irrelevance, of supernaturalism. But science is more than physics and chemistry, more even than biology, and the human sciences challenge a lot of beliefs held by many atheists. The modern efflorescence of evolutionarily inspired psychology and sociology tells us that the elements of religion are natural, and unavoidable, and sometimes useful; that they are present in all societies, whether literate or pre-literate, whether in states or hunter-gatherer, though they are combined in very different forms of social organisation. So we learn at the very least that they can't be abolished. This doesn't show that they need be combined into things we call "religions"; but at the very least they will tend to combine into social groupings and mechanisms which perform the same functions. Further, the sociology of religion shows clearly that modern monotheistic religion is not an intellectual pursuit. People do not join churches because they agree with the doctrines. Nor do they often leave for intellectual reasons. They join – and leave – for all sorts of largely social reasons, and even within the churches, their allegiance to, and knowledge of, the official doctrine is slight. Heresy can matter enormously, but that's because it defines an outgroup. And the execration of heretics flourishes among atheist societies, too. It seems to be very widespread social mechanism. |

| Column |

Brains, Mind, MoralityDo we have any obligation to keep alive people whose brains no longer work properly?  The easiest way to change a mind forever is to destroy bits of the brain. It's not very precise, but it is remarkably effective. This has been known ever since Phineas Gage, an enthusiastic railway worker, detonated the charge of dynamite he was tamping into a hole, so that the spike he was tamping it with flew out, smashed his cheekbone and burst through his brain and out the top of his skull. He lived for years after that but he had lost almost all his inhibitions. They had somehow been contained in the part of his brain that was destroyed. This story is known to everyone interested in the relationship between mind and brain. But there is one strange and horrifying pendant which I only learned last week, at a seminar in Cambridge. Brain injuries of a certain sort can disinhibit adults. In children they can permanently prevent the formation of inhibitions at all. Such things are fortunately very rare. But they are recorded, especially at the university of Iowa, which collects patients from all over the state and thus as an unmatched, unenviable knowledge of ghastly childhood brain injuries, whether from cancers, epilepsies or simple accidents. The classic paper on this is more than ten years old: in 1999 Antonio Damasio and colleagues at the University of Iowa published a study of two young adults who simply did not live in the same moral universe as the rest of us. One of them was a girl who had been run over as a toddler. She appeared to make a quick and full recovery. But as an adolescent, she became more or less psychopathic. Although intelligent and academically capable, she stole, she fought, she lied chronically; at 18 she had a child whom she neglected. Most tellingly of all, she could not see anything wrong with her behaviour, nor even pretend that she did. |

| Column |

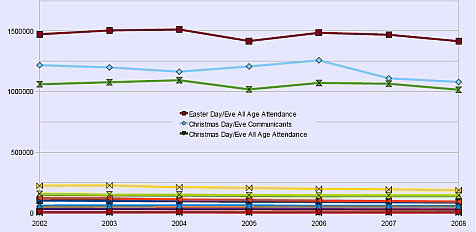

Church Statistics: Not Many DeadThe annual church attendance statistics tell a story of very gradual change--which is clearer in pictures than in words.  When I was first working at the Independent we were very proud of our photographs. One day there was a tragic little item on the PA wire about a young man who had hanged himself because he had been turned down for a job because of his terrible acne. The news editor looked at it. "This is a story crying out for a picture" he said. That kind of demonstrative hard-boiledness is one journalistic vice. But the annual display of Church of England attendance figures brings out another one: the need to make sure that everything is exciting. I am reasonably certain that all the papers who notice it tomorrow will carry stories saying that the decline in church attendance continues. This is true, but it is another story crying out for a picture. And what the picture shows is not a graph that you could ski down, but one which would make for one of the duller stretches of a long cross-country trudge. Nothing dramatic is happening. The Church of England says it's a little less of a decline; its various enemies say it's huge; journalists say that whatever it is, it must be dramatic. (note how the axis in this graph is chosen to maximise the drama) But, actually, what this suggests is that the action is happening elsewhere. There are graphs that would like much hillier: the collapse in Roman Catholic vocations was one; the rise in pentecostal subcultures here is probably another. |

| Column |

British Creationists: Some NumbersThose who reject Darwinism in Britain are numerous, largely irreligious, and ignorant of science.  The previous blog discussed how creationist opinion formers think: given that formal creationism is a belief that must be taught, this seems a sensible line of enquiry. By formal creationism, I mean the belief that most scientists have more or less malevolently misinterpreted the data for the last 200 years to prove that the Bible is not literally true. That survey dealt only with 50 opinion formers, interviewed in depth. But how many people do they represent? The answer to that comes from an earlier Theos survey, published this spring, which contained truly shocking figures as to the amount of biological ignorance in the country; but at the same time, it suggested that this had nothing much to do with religion. How could it, when the number of people reporting either Young Earth creationism, or ID, at 25% is something like five times as large as the combined Muslim and evangelical population of this country? Twice as many people are confused about what they believe, and only another quarter are convinced of the truth of evolution. These results were obtained by a fairly sophisticated set of questions, designed to discover what people actually believed, rather than the labels they would attach to it. Much of it, I think, is the result of innumeracy in general: someone for whom all numbers above about a thousand are indistinguishable blur may very well think that the earth is 10,000 years old and mean by this that it is really really seriously, like, old. Such people don't pose any threat to the teaching of science in schools. They just make it look entirely pointless, since they have themselves been "educated". But that is a different and more serious problem than religious creationism. The anti-Darwinians interviewed in the most recent survey are a tiny, articulate and self-conscious minority. The real problem for public understanding, as anyone knows who has done any science writing, are the millions of people whose position is that they don't know, don't care, and don't want to do either. |

| Column |

Who Are the Creationists?The first scientific study of British creationist reasoning shows people too confused to be a movement  The admirable Theos project on Darwin concludes with the publication of a study on how British creationists think (pdf). To forestall the entirely predictable accusation that it's not science if Christians do it, this research was actually carried out on Theos's behalf by the ethnographic research firm ESRO. By interviewing 50 prominent anti-evolutionists, mostly Christians, but some Muslims and agnostics too, whose views ranged from intelligent design to young earth creationism, the researchers managed to get a picture of a movement whose most interesting characteristic is that it isn't one. In fact one of their interviewees was taught at Sussex by John Maynard Smith, an experience he describes as "a real privilege". Interviewees did not seem to be united in either a geographical or a political sense. They did not necessarily belong to or attend any creationist groups or organisations and, where they did, they belonged to different ones. They did not keep contact with their counterparts in the US and they did not necessarily communicate with each other. There were vehement disagreements over theological matters and over the means by which evolution scepticism could be promoted. Intelligent design had not successfully created a paradigm through which all evolution sceptics might engage in the debate around evolution. About half of their interviewees were full-on young earth creationists, believing in the literal truth of the Bible, and hence of a 6,000-year-old earth: but the interesting thing about this is that much of their propaganda was directed not against the evil Darwinians, but against the backslidden old-earth creationists, or, worse, ID-ers. Although the interviewees were anonymous, one of these backsliders is described as the principal of a theological college. But it is important, I think, to notice that the reason for rejecting evolution, for those who put biblical authority first, is not that biology couldn't work that way (a later rationalisation) but that an evolutionary story is incompatible with the age of the earth. Although both terms creep into the debate over evolution, being YEC [young earth] or OEC [old earth] does not in itself imply anything necessarily about beliefs regarding the truth of evolution; rather, they are positions on the age of the earth (as taught by the Bible) which have implications for beliefs about evolution This is an important example of the way in which rejecting evolution leads inexorably to the rejection of the whole of modern science – history, ecology, and physics as well as biology. |

| Column |

Learning from CreationismThe spread of creationism, and climate denialism is not the result of gullibility but of mistrust. It's easy to suppose that the whole vast apparatus of modern creationism has taught us nothing at all. All those books, the endless arguments on usenet and then on the web, the museums, the theme parks, the teaching materials – all of it dedicated to teaching lies; none of it contributing so much as a moment's thought to the advance of knowledge. But I think there is one important thing which all these millions of hours of labour has shown that could not have been learned any other way. It wasn't intentional. But creationists have proved that most scientists have a very naïve and inadequate idea of evidence. In particular, they believe that the justification for believing scientific claims is that they are reproducible and produce irrefutable evidence. The creationists have shown this is mistaken. Of course the experiment must be reproducible. Of course the results must be clear. But it's just as important that we take both these things on trust. When scientists report results we take them at their word. Without a belief that they are trustworthy, nothing they do compels belief. That is why fakery, when detected, must be so severely punished. This was known before creationism was a problem. Richard Lewontin has written about the way in which even scientists cannot still less reproduce and judge, experiments outside their fields. But he's a sort of Marxist and easy to ignore. In any case, his assumption was |

| Column |

We're Doomed Without a Green ReligionArguments about climate change show up the incoherence of any purely individual morality.  The justification for burning heretics was perfectly simple: dissent threatened the survival of society. Nothing was worse than anarchy. This is a viewpoint most people in the West today find pretty much incomprehensible. It is a self-evident truth to them that morality must be a matter of individual choice. And if you believe that, the arguments around the Tim Nicholson case are very difficult to resolve. If there is a moral imperative to preserve the human race, or as much of it as possible, collective consequences must follow. It is not enough for us to do the right thing. Others must as well. If you don't believe that, then there is no point in agitating for success in Copenhagen. But if collective consequences follow, others must be forced to do things against their will by our moral imperatives. This is exactly the quality that is supposed to be so very obnoxious about religion. The idea that morality is and must be a matter of individual choice is taken as axiomatic in these debates. It is thought true in the sense that it is held to describe a fact about the world. Very often the same people who believe this will also believe, and maintain with equal vehemence in other contexts the belief that morals are merely opinions, or at least that there couldn't in the nature of things be moral facts: true or false statements about whether something or someone is good or bad. This was neatly if not nicely expressed by one of the commenters on Tim Nicholson's article here, who said You may believe less flying and driving, and more wind farms, and so on to be moral imperatives. I don't. You are entitled to your beliefs, and should not be persecuted for them. But they are just beliefs. You want to argue the politics of how to respond to climate change: great. But you can stop wrapping your proposed solutions up in 'moral imperative' cotton wool. These are not the only confusions which the Nicholson case raises. Many people who are upset by the court's equating a scientific opinion with a religion belief suppose that science is true and rational, religion is false and irrational, and that this division of the world is itself factual and rational. If this is how the world appears to you, then there is no question that climate change is not a religion. That would mean that it wasn't really happening, and that we were free to ignore it. Both supporters and opponents of environmentalism can often agree both that it might be a religion and that would be a bad thing. This is why, in general, the people who maintain that environmentalism is like a religion are opposed to it; while those in favour deny it is anything like a religion. (A further complication is supplied by right-wing Christians like Daniel Johnson who maintain that religion is a good thing, but environmentalism is a false religion.) |

| Article |

The Music of the SpheresKepler founded modern astronomy by looking for a harmony that we wouldn't recognise as scientific at all.  Paper darkens as it grows old, but vellum just goes duller white, like the belly of a snake: looking at some of the manuscripts through which learning made its serpentine passage across the medieval world makes it obvious that you couldn't call those ages "dark". The library of The Royal Observatory in Edinburgh holds one of the finest collections of early astronomical books and manuscripts in the world, collected by Lord Crawford in the 19th century. He left them to the city on condition that they built an observatory to house them. Being civilised, the city fathers did. So there I was on Tuesday, touching the vellum of a 13th century manuscript of Alhazen, another of Aristotle, and then a first edition of Copernicus' De Revolutionibus and one of Kepler's Nova Astronomia. In the shelves on the wall were Galileo's works. We were meant to be making a radio programme – an interval talk for Radio 3 – but the producer and I and our guest Ken MacLeod just frolicked round that room of priceless books like salmon woken by a spate. Serious work was impossible for a while. There was nothing to say that was adequate in the face of so much beauty and so much history; for anyone who writes, the feel of a physical object which has been read for 800 years is a quite extraordinary thrill. Alhazen is almost forgotten now, and Aristotle little read or acknowledged outside the Roman Catholic intelligentsia. But when those first manuscripts were only three hundred years old, the books which we all know have changed the world were published. First there |

| Radio Broadcast |

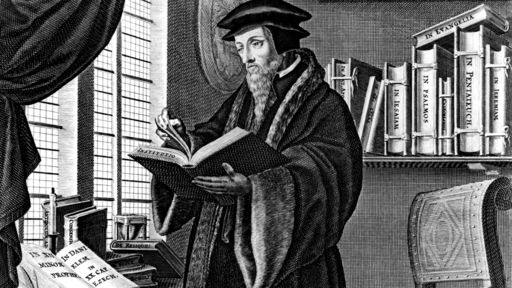

Smashing the IdolsWriter Andrew Brown explores the controversial cultural and theological legacy of Calvinism.  Perhaps nobody has ever looked at death, hell, human nature and God quite so uncompromisingly as the lawyer born in Noyon in 1509, who gave his name to one of the fiercest and most influential forms of Protestantism. John Calvin believed in a world where God controlled all, and who went to heaven and who went to hell was predestined - Christ died for only a select few. Nothing except the Bible was tolerated in church which led to Calvinism's terrible reputation as a destroyer of art. It is argued that Calvinism influenced many aspects of our modern society - science, economics, philosophy, democracy - but such claims are considered by historians to be overblown. They instead highlight the strangely paradoxical qualities of a faith which fuelled both the religious wars of the 17th century and the enlightenment which followed. Moving from Geneva to Scotland, and talking to historians Diarmaid MacCulloch and Bill Naphy, as well as novelists Marilynne Robinson and James Robertson, Andrew explores the sometimes unexpected legacies of this extraordinarily polarising system of belief. With works by Calvin read by John Sessions and music by Cappella Nova. read more… listen… [85 minutes, mp3 format] |

| Column |

Sam Harris and Francis CollinsAtheism can express intolerance and hatred quite as well as religion. Sam Harris proves it.  Anyone tempted to believe that the abolition of religion would make the world a wiser and better place should study the works of Sam Harris. Shallow, narrow, and self-righteous, he defends and embodies all of the traits that have made organised religion repulsive; and he does so in the name of atheism and rationality. He has, for example, defended torture, ("restraint in the use of torture cannot be reconciled with our willingness to wage war in the first place") attacked religious toleration in ways that would make Pio Nono blush: "We can no more tolerate a diversity of religious beliefs than a diversity of beliefs about epidemiology and basic hygiene" ; he has claimed that there are some ideas so terrible that we may be justified in killing people just for believing them. Naturally, he also believes that the Nazis were really mere catspaws of the Christians. ("Knowingly or not, the Nazis were agents of religion"). "A bold and exhilarating thesis" is what Johann Hari said of Harris's first book (from which the quotes above are taken), though on reflection he might think it more bold than exhilarating. Richard Dawkins was more wordily enthusiastic in a preface for Harris's next: "Every word zings like an elegantly fletched arrow from a taut bowstring and flies in a gratifyingly swift arc to the target, where it thuds satisfyingly into the bullseye." (where else does he expect to find the bullseye?) Hundreds of thousands of people bought the books, and perhaps the ideas in them. And now Harris has had an op-ed in the New York Times, in which, in his bold and exhilarating way, he makes the case against appointing a Christian scientist, Francis Collins, to the important American government post of Director of the National Institutes of Health. This is not because Collins is a bad scientist. He is, actually, quite extraordinarily distinguished, both as a scientist and as an administrator: his previous job was running the Human Genome Project as the successor to James Watson. But he is, unashamedly, a Christian. He's not a creationist, and he does science without expecting God to interfere. But he believes in God; he prays, and this is for Harris sufficient reason to exclude him from a job directing medical research. Of course this is a fantastically illiberal and embryonically totalitarian position that goes against every possible notion of human rights and even the American constitution. If we follow Harris, government jobs are to be handed out on the basis of religious beliefs or lack thereof. But what is really astonishing and depressing is how little faith it shows in science itself. |

| Article |

How to Design the Perfect Baby Belinda Kembery was pregnant with her second child when she realised something was wrong with Robbie, her first. "He didn't quite get to walking, and then, when he was just over a year old, he stopped sleeping well. He would wake in the night and it would be as though he'd just had a shot of caffeine... he would be rocking backwards and forwards, very agitated, and it would be very hard to calm him down." Kembery, 41, a solicitor before her marriage, is sitting in a spacious, shining kitchen conservatory in Clapham, south London, a room so calm and tidy you would think it had never had children in it at all. "The next sign we noticed was that he would be sitting up or crawling around, and he would suddenly fall over. That's why we put him in a bike helmet. One day, watching him very closely, we realised he was having a blackout. I went to the GP. We had weeks of appointments - brain scans, blood tests, lumbar punctures. The day we had the diagnosis, I was 22 weeks pregnant." The child she was then carrying is now a healthy, seven-year-old boy. But Robbie, she was told, had Batten disease, caused by the malfunction of a single gene - CLN1, on chromosome 1, in Robbie's case. Normal copies code for a protein that helps to break down fatty molecules - lipofuscins - within brain and nerve cells. Without it, the cells are choked in fat and die. The first symptoms are seizures; then comes blindness, dumbness, paralysis and worse. Robbie would never walk, never speak, and by three he could not see nor swallow. The weakened muscles of his diaphragm gave him acid reflux so terrible that it stripped the enamel from his teeth. Eventually, an operation closed off the top of his stomach. Today, he is fed through a tube. "Nothing at all had prepared us for this diagnosis," Belinda says. "In the hospital, they asked me to count the number of seizures he had had, and I got to 100 and stopped counting - and that was before lunchtime. Poor little thing. He was really suffering. They told us |

| Column |

Errors of an Old AtheistSigmund Freud is despised by most scientists today. But many would accept unthinkingly his views on religion.  Psychoanalysis unfortunately has hardly anything to say about the derivation of beauty ... All that seems certain is its derivation from the field of sexual feeling. You have to admire that use of "certain". But the thing that really caught my eye was his attack on religion, because it states very clearly one of the central New Atheist rhetorical moves. This is to define religion as the belief system of ignorant fools, the people whom Freud, writing in a much less democratic age, did not hesitate to call "the common man". Watch how it's done. He is concerned, he says, less withthe deepest sources of the religious feeling than with what the common man understands by his religion–with the system ; doctrines and promises which on the one hand explains to him the riddles of this world with enviable completeness, and, on the other, assures him that a careful Providence will watch over his life and will compensate him in a future existence for any frustrations he suffers here. The common man cannot imagine this Providence otherwise than in the figure of an enormously exalted father. Only such a being can understand the needs of the children of men and be softened by their prayers and placated by the signs of their remorse. Having set up a system in which only fools could believe, he then points out that only fools could believe in it: The whole thing is so patently infantile, so foreign to reality, that to anyone with a friendly attitude to humanity it is painful to think that the great majority of mortals will never be able rise above this view of life. Yet this, he says, is "the only religion which ought to bear that name." Why? I really don't see this. Intelligent, cultured and brave believers do pose a real problem for atheists, but it's not one we honourably solve by simply denying their existence. Freud goes on to dismiss anyone with the brains to see that a God who is merely an enormously exalted father can't be worth worshipping – yet who still isn't an atheist – on the grounds that they are not getting real religion at all: |

| Column |

Enemies of Creationism May Be Hindering Science TeachersA US judge's ruling is a warning to those who want to teach real science in schools that they need to change their tactics.  A district court judge in southern California has ruled that a teacher who described creationism as "superstitious nonsense" was making a religious statement, which is impermissible in US public schools. On the face of it, this is completely absurd, even for southern California. Creationism is superstitious nonsense, and teachers should be able to say so. But when you look at the background, the case becomes in some respects less absurd, but also more threatening – especially for hardline rationalists such as Richard Dawkins, who would like to dismiss creationism as beneath contempt. The first thing to say is that Judge James Selna seems, from his 37-page ruling, to be no friend of fundamentalists. Of the 20 complaints made against the teacher, James Corbett, he dismissed 19; many of them on the face of it much more anti-religious than calling creationism "superstitious nonsense". Second, the lawsuit was clearly a premeditated strike in the culture wars. Orange County, where Capistrano Valley high school is located, is one of the most conservative places in the US. Corbett had been involved in a controversy over John Peloza, a science teacher at the school who in 1994 sued his employers, demanding the right to teach creationism in his science classes. He lost. Some fundamentalist parents were obviously out to get Corbett. His lessons were secretly recorded to compile evidence against him, and the words for which he has been found guilty were part of a discussion, or argument, about the earlier case: "I will not leave John Peloza alone to propagandise kids with this religious, superstitious nonsense," he said, and those were the words that Judge Selna has found unconstitutional. Clearly, Corbett walked into a trap that had been dug specifically for him. The fundamentalist lawsuit demanded that he be sacked, rather than pay damages, though both the school and the judge rejected this demand. From the material quoted in the judgment it does look as if Corbett was the kind of atheist concerned to eradicate religious belief; but you might argue that he was just trying to get students to think. He claimed to have been selectively quoted in some instances, but in |

| Column |

Why Atheism Must be Taught Several people in comments seemed bewildered that I think you have to teach children atheism. There's a confusion here that needs clearing up. If by atheism you mean "not being a Christian" of course you don't have to teach this explicitly in modern Britain, any more than you have to teach your children not to believe in Shinto deities of ancient Egyptian ones. It's the default position of the culture. But any worthwhile atheism is far more than not believing in some particular god. It's supposed to be a superior replacement for all religious belief. Even if it is not a doctrine, it is an attitude of mind, a way of looking at the world and of sifting evidence about it. This has to be taught. One of the classic, if rather squirm-making examples of this process is supplied by Richard Dawkins himself, with an anecdote where his six-year-old daughter tells him that wildflowers "are there to make the world pretty and to help the bees make honey". So of course, he has to explain to her that this is an illusion, and they are really there to serve the purposes of DNA. But even if you're not a doctrinaire atheist you have to teach children the values and skills that you treasure or else they will die. This is something common to religious and atheistic approaches to life. It would still be true even if children did not in fact have a bias towards supernatural rather than naturalistic explanations. I am sure that they do, and there's plenty of research to show the process. In that sense, it seems to me completely incontestable that atheism has to be taught, even if the process consists largely of the transmission of attitudes and habits of mind rather than dogmatic statements. Not to see this is an instance of a more general blindness, which Xenophanes ascribed to theologians: "The gods of the swarthy and flat nosed; the gods of the Thracians arre fair haired and blue eyed ..." |

| Column |

Science vs Superstition, not Science vs ReligionWe are not going to understand the growth of creationism in modern England so long as we think of it as a primarily Christian phenomenon, or even a religious one. Take a look at the most recent surveys of creationist belief among teachers and among the general public. One was conducted by Theos, the Christian thinktank, and has been attacked by the BHA – more of this later – and the other measured attitudes towards creationism among school teachers. That found that nearly a third of teachers with science as a specialism saw nothing wrong with teaching creationism in class. Now, I have only come across one school where an open attempt was made to do this – the notorious Emmanuel Academy in Gateshead. But the headmaster there told me, and I have no reason to doubt this, that although he was himself an evangelical Christian, the impulse towards creationism in science classes had come from Muslim parents. So, does this prove that the problem is simply one of religion versus science? Not if the BHA is right about the decline of religious observance. Their most recent press release claims that less than 10% of the British population is religiously observant. But the figures for the rejection of evolution produced in the latest Theos survey completely dwarf the most generous estimates for religious observance. |

| Column |