Chris Mooney

Chris Mooney is a science journalist, author, lecturer, commentator, and blogger whose work focuses on issues arising at the intersection of science, politics, and culture. His articles have been published in Wired, Harper's, New Scientist, Slate, Salon, American Scholar, The New Republic, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and Boston Globe. His 2007 book Storm World: Hurricanes, Politics, and the Battle Over Global Warming was selected as a best book of the year in the science category by Publisher's Weekly and a best science and technology book of 2007 by Library Journal. He is currently at work on his fourth book.

| Radio Broadcast |

Robert McCauley: Why Religion is Natural(And Science is Not)  Over the last decade, there have been many calls in the secular community for increased criticism of religion, and increased activism to help loosen its grip on the public. But what if the human brain itself is aligned against that endeavor? That's the argument made by cognitive scientist Robert McCauley in his new book, Why Religion is Natural and Science is Not. In it, he lays out a cognitive theory about why our minds, from a very early state of development, seem predisposed toward religious belief—and not predisposed towards the difficult explanations and understandings that science offers. If McCauley is right, spreading secularism and critical thinking may always be a difficult battle—although one no less worthy of undertaking. Dr. McCauley is University Professor and Director of the Center for Mind, Brain, and Culture at Emory University. He is also the author of Rethinking Religion and Bringing Ritual to Mind. |

| Article |

The Science of Why We Don't Believe ScienceHow our brains fool us on climate, creationism, and the vaccine-autism link.  "A MAN WITH A CONVICTION is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point." So wrote the celebrated Stanford University psychologist Leon Festinger [1] (PDF), in a passage that might have been referring to climate change denial—the persistent rejection, on the part of so many Americans today, of what we know about global warming and its human causes. But it was too early for that—this was the 1950s—and Festinger was actually describing a famous case study [2] in psychology. Festinger and several of his colleagues had infiltrated the Seekers, a small Chicago-area cult whose members thought they were communicating with aliens—including one, "Sananda," who they believed was the astral incarnation of Jesus Christ. The group was led by Dorothy Martin, a Dianetics devotee who transcribed the interstellar messages through automatic writing. Through her, the aliens had given the precise date of an Earth-rending cataclysm: December 21, 1954. Some of Martin's followers quit their jobs and sold their property, expecting to be rescued by a flying saucer when the continent split asunder and a new sea swallowed much of the United States. The disciples even went so far as to remove brassieres and rip zippers out of their trousers—the metal, they believed, would pose a danger on the spacecraft. Festinger and his team were with the cult when the prophecy failed. First, the "boys upstairs" (as the aliens were sometimes called) did not show up and rescue the Seekers. Then December 21 arrived without incident. It was the moment Festinger had been waiting for: How would people so emotionally invested in a belief system react, now that it had been soundly refuted? |

| Radio Broadcast |

Bioethics Comes of Age Our guest this week is Arthur Caplan, sometimes called the country's "most quoted bioethicist" and director of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania. In this wide ranging episode, Caplan discusses not only the latest issues and problems in his field, but also how those issues have changed over time. Fresh from the ideological fights of the Bush administration-over culture war issues like stem cells, cloning, and Terri Schiavo-bioethicists like Caplan are now more focused on practical matters like access to healthcare. And so is the country as a whole. However, the religious right remains active-encouraging pharmacists to claim a right of conscience and refuse to give patients the morning after pill. Meanwhile, as an excuse to restrict abortion, some are now also making the dubious assertion that fetuses can feel pain at 20 weeks of gestation. So in this interview, Caplan surveys the leading problems in bioethics today-and those we'll be facing in the very near future. Arthur Caplan is the Emmanuel and Robert Hart Director of the Center for Bioethics, and the Sydney D Caplan Professor of Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He's the author or editor of twenty-nine books-most recently Smart Mice Not So Smart People (Rowman Littlefield, 2006) and the Penn Guide to Bioethics (Springer, 2009)—and over 500 papers in refereed journals. He writes a regular column on bioethics for MSNBC.com. |

| Column |

Fixing the Economy the Scientific WayWorried about the economy? Try investing in scientific research — it can solve problems and create jobs.  Here are two facts that might seem unrelated: 1) Most Americans cannot name a living scientist. 2) Over the last two years, by far the most pressing problems in the country have been the economy and the cost of healthcare (a chief concern of President Obama's deficit commission). What if we told you solving the first will help us fix the second? Without ramping up our investments in science and research — a matter barely on the public's radar in a country where 65% of the citizens can't name a living scientist and another 18% try but get it wrong — we'll be hobbled in trying to fix our long-term economic problems. That's because science creates jobs, and it can also reduce healthcare costs related to the aging of the population. Take jobs first: This has been a theme hammered home by the National Academy of Sciences. In its two "Gathering Storm" reports released in recent years, the academy has argued strongly that our future prosperity depends on investments made now in research and innovation. The basic premise rests on the work of Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow, who documented that advances in technology and knowledge drove U.S. economic growth in the first half of the 20th century. If it was true then, it's even more so in today's information economy. Consider the economic reverberations of dramatically increasing the capacity of the microchip. As the academy unforgettably put it: "It enabled entrepreneurs to replace tape recorders with iPods, maps with GPS, pay phones with cellphones, two-dimensional X-rays with three-dimensional CT scans, paperbacks with electronic books, slide rules with computers, and much, much more." It's dramatic testimony to the economic power of scientific advances. And yet over the four decades from 1964 to 2004, our government's support of science declined 60% as a portion of GDP. Meanwhile, other countries aren't holding back: China is now the world leader in investing in clean energy, which will surely be one of the industries of the future. Overall, China invested $34.6 billion in the sector in 2009; the U.S. invested $18.6 billion. |

| Interview |

InterviewSkeptConnect interviews Chris Mooney, author and science journalist. Chris speaks about religion, science and politics – oh, and Rock & Roll! Doesn’t get better than that! |

| Radio Broadcast |

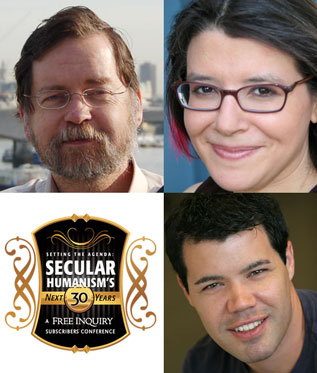

New Atheism or Accommodation? Recently at the 30th anniversary conference of the Council for Secular Humanism in Los Angeles, leading science blogger PZ Myers and Point of Inquiry host Chris Mooney appeared together on a panel to discuss the questions, "How should secular humanists respond to science and religion? If we champion science, must we oppose faith? How best to approach flashpoints like evolution education?" It's a subject about which they are known to... er, differ. The moderator was Jennifer Michael Hecht, the author of Doubt: A History. The next day, the three reprised their public debate for a special episode of Point of Inquiry, with Hecht sitting in as a guest host in Mooney's stead. This is the unedited cut of their three way conversation. PZ Myers is a biologist at the University of Minnesota-Morris who, in addition to his duties as a teacher of biology and especially of development and evolution, likes to spend his spare time poking at the follies of creationists, Christians, crystal-gazers, Muslims, right-wing politicians, apologists for religion, and anyone who doesn't appreciate how much the beauty of reality exceeds that of ignorant myth. Jennifer Michael Hecht is the author of award-winning books of philosophy, history, and poetry, including: Doubt: A History (HarperCollins, 2003); The End of the Soul: Scientific Modernity, Atheism and Anthropology (Columbia University Press, 2003); and The Happiness Myth, (HarperCollins in 2007). Her work appears in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Republic, and The New Yorker. Hecht earned her Ph.D. in History from Columbia University in 1995 and now teaches in the graduate writing program of The New School University. |

| Column |

Spirituality Can Bridge Science-Religion Divide We hear a lot these days about the "conflict" between science and religion — the atheists and the fundamentalists, it seems, are constantly blasting one another. But what's rarely noted is that even as science-religion warriors clash by night, in the morning they'll see the battlefield has shifted beneath them. Across the Western world — including the United States — traditional religion is in decline, even as there has been a surge of interest in "spirituality." What's more, the latter concept is increasingly being redefined in our culture so that it refers to something very much separable from, and potentially broader than, religious faith. Nowadays, unlike in prior centuries, spirituality and religion are no longer thought to exist in a one-to-one relationship. This is a fundamental change, and it strongly undermines the old conflict story about science and religion. For once you start talking about science and spirituality, the dynamic shifts dramatically. Common groundThe old science-religion story goes like this: The so-called New Atheists, such as Richard Dawkins, uncompromisingly blast faith, even as religiously driven "intelligent design" proponents repeatedly undermine science. And while most of us don't fit into either of these camps, the extremes also target those in the middle. The New Atheists aim considerable fire toward moderate religious believers who are also top scientists, such as National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins. Meanwhile, people like Collins get regular flack from the "intelligent design" crowd as well. In this schematic, the battle lines may appear drawn, the conflict inescapable. But once spirituality enters the picture, there seems to be common ground after all. Spirituality is something everyone can have — even atheists. In its most expansive sense, it could simply be taken to refer to any individual's particular quest to discover that which is held sacred. That needn't be a deity or supernatural entity. As the French sociologist Emile Durkheim noted in 1915: "By sacred things one must not understand simply those personal beings which are called Gods or spirits; a rock, a tree, a spring, a pebble, a piece of wood, a house, in a word, anything can be sacred." |

| Column |

The Climate Scandal that Never Was In the grand saga of political battles over climate research, there is no event more pivotal, or more damaging, than what has come to be called "climategate" - the late-2009 theft and exposure of a trove of emails from the Climate Research Unit (CRU) at the University of East Anglia in the UK. Fred Pearce's The Climate Files, based on his 12-part investigative series for The Guardian newspaper in London, is the first book-length attempt to cover the furore. Some scientists faulted the Guardian series when it appeared, and similar objections apply to this book. Pearce (who is a consultant for New Scientist) writes as though he is covering a real scandal, and takes a "pox on both houses" approach to the scientists who wrote the emails and the climate sceptics who hounded them endlessly - and finally came away with a massive PR victory. But that's far too "balanced" an account. In truth, climategate was a pseudo-scandal, and the worst that can be said of the scientists is that they wrote some ill-advised things. "I've written some pretty awful emails," admitted Phil Jones, director of the CRU at the time. The scientists also resisted turning over their data when battered by requests for it - requests from climate sceptics who dominate the blogosphere and don't play by the usual rules. But there is nothing very surprising, much less scandalous, about such behaviour. Yes, a "bunker mentality" developed among the scientists; they were "huddling together in the storm," in Pearce's words. But there really was a storm. They were under attack. In this situation, the scientists proved all too human - not frauds, criminals or liars. So why were their hacked emails such big news? Because they were taken out of context and made to appear scandalous. Pearce repeatedly faults the sceptics for such behaviour. Yet he too makes the scientists' private emails the centrepiece of the story. Pearce's investigations don't show any great "smoking gun" offences by the scientists - yet he still finds fault. And who wouldn't, when they can read their private comments in the heat of the battle? (I can't help but wonder what Pearce might think if he had the sceptics' private emails too.) |

| Column |

If Scientists Want to Educate the PublicThey should start by listening  Whenever controversies arise that pit scientists against segments of the U.S. public -- the evolution debate, say, or the fight over vaccination -- a predictable dance seems to unfold. One the one hand, the nonscientists appear almost entirely impervious to scientific data that undermine their opinions and prone to arguing back with technical claims that are of dubious merit. In response, the scientists shake their heads and lament that if only the public weren't so ignorant, these kinds of misunderstandings wouldn't occur. But what if the fault actually lies with both sides? We've been aware for a long time that Americans don't know much about science. Surveys that measure the public's views on evolution, climate change, the big bang and even the idea that the Earth revolves around the sun yield a huge gap between what science tells us and what the public believes. But that's not the whole story. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences convened a series of workshops on this topic over the past year and a half, and many of the scientists and other experts who participated concluded that, as much as the public misunderstands science, scientists misunderstand the public. In particular, they often fail to realize that a more scientifically informed public is not necessarily a public that will more frequently side with scientists. Take climate change. The battle over global warming has raged for more than a decade, with experts still stunned by the willingness of their political opponents to distort scientific conclusions. They conclude, not illogically, that they're dealing with a problem of misinformation or downright ignorance -- one that can be fixed only by setting the record straight. |

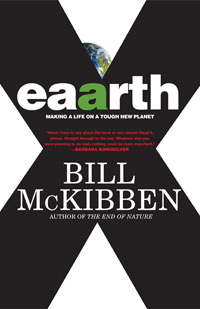

| Broadcast |

Bill McKibben on Our Strange New EaarthNew Point of Inquiry  But according to Bill McKibben, that’s a 1980s view. As McKibben writes in his new book Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet, the increasingly open secret is that global warming happened already. We’ve passed the threshold, and the planet isn’t at all the same. It’s less climatically stable. Its weather is haywire. It has less ice, more drought, higher seas, heavier storms. It even appears different from space. And that’s just the beginning of the earth-shattering changes in store—a small sampling of what it’s like to trade a familiar planet (Earth) for one that’s new and strange (Eaarth). We’ll survive on this sci-fi world, this terra incognita—but we may not like it very much. And we may have to change some fundamental habits along the way. Eaarth, argues McKibben, is our greatest failure. |

| Interview |

The Menace of DenialismInterview with Michael Specter  This week, we learned that J. Craig Venter has at long last created a synthetic organism—a simple life form constructed, for the first time, by man. Let the controversy begin—and if New Yorker staff writer Michael Specter is correct, the denial of science will be riding hard alongside it. In his recent book Denialism: How Irrational Thinking Hinders Scientific Progress, Harms the Planet, and Threatens Our Lives, Specter charts how our resistance to vaccination and genetically modified foods, and our wild embrace of questionable health remedies, are the latest hallmarks of an all-too-trendy form of fuzzy thinking—one that exists just as much on the political left as on the right. And it’s not just on current science-based issues that denialism occurs. The phenomenon also threatens our ability to handle emerging science policy problems—over the development of personalized medicine, for instance, or of synthetic biology. How can we make good decisions when again and again, much of the public resists inconvenient facts, statistical thinking, and the sensible balancing of risks? Michael Specter has been a New Yorker staff writer since 1998. Before that, he was a foreign correspondent for the New York Times and the national science reporter for the Washington Post. At the New Yorker, Specter has covered the global AIDS epidemic, avian flu, malaria, the world’s diminishing freshwater resources, synthetic biology and the debate over our carbon footprint. He has also published many profiles of subjects including Lance Armstrong, ethicist Peter Singer, and Sean (P. Diddy) Combs. In 2002, Specter received the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Science Journalism Award for his article "Rethinking the Brain," about the scientific basis of how we learn. |

| Interview |

How Religious Are Scientists?An interview with Elaine Howard Ecklund  It’s hard to think of an issue more contentious these days than the relationship between faith and science. If you have any doubt, just flip over to the science blogosphere: You’ll see the argument everywhere. In the scholarly arena, meanwhile, the topic has been approached from a number of angles: by historians of science, for example, and philosophers. However, relatively little data from the social sciences has been available concerning what today’s scientists actually think about faith. Today’s Point of Inquiry guest, sociologist Dr. Elaine Ecklund of Rice University, is changing that. Over the past four years, she has undertaken a massive survey of the religious beliefs of elite American scientists at 21 top universities. It’s all reported in her new book Science vs. Religion: What Scientists Really Think. Ecklund’s findings are pretty surprising. The scientists in her survey are much less religious than the American public, of course—but they’re also much more religious, and more "spiritual," than you might expect. For those interested in debating the relationship between science and religion, it seems safe to say that her new data will be hard to ignore. Elaine Howard Ecklund is a member of the sociology faculty at Rice University, where she is also Director of the Program on Religion and Public Life at the Institute for Urban Research. Her research centrally focuses on the ways science and religion intersect with other life spheres, and it has been prominently covered in USA Today, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Newsweek, The Washington Post, and other prominent news media outlets. Ecklund is also the author of two books published by Oxford University Press: Korean American Evangelicals: New Models for Civic Life (2008), and more recently the new book Science vs. Religion: What Scientists Really Think (2010) |

| Discussion |

Denialism: Media in the Age of Disinformation

A few hundred years after the Enlightenment, western civilization is rushing back to the Dark Ages. The causes are debatable, but, argue these science journalists, the public increasingly rejects the findings of science, from climate change to evolution, and is turning away from rationality and reason in general. "People are afraid of anything that will hammer away at their preconceived notions," says Michael Specter. He points to the fanatic opposition in some quarters to genetically engineered foods, and the worship of organic products. Almost everything we eat is the result of genetic modification, he notes, and "organics kill people, too." It doesn’t make sense to think that returning to "the old ways" will keep us healthy and supply the world with food. "We’re hurting ourselves in lots of ways," says Specter, when people insist on believing what they want. Human nature plays a big part in feeding denialism, believes Chris Mooney. "We all ... argue against information that contradicts our existing worldview." The unfortunate evolution of media in the digital age is feeding our inherent "confirmation bias," and today "Americans with different political leanings construct different realities." We must "give up" on the idea that truth triumphs and society advances as more people become critical thinkers. Concludes Mooney, "We have to work with the media and brains we have, and seek realistic change." |

| Article |

The Death of Science Writing, and the Future of CatastropheAn interview with Andrew Revkin  We live in a science centered age–a time of private spaceflight and personalized medicine, amid path-breaking advances in biotechnology and nanotechnology. And we face science centered risks: climate and energy crises, biological and nuclear terror threats, mega-disasters and global pandemics. So you would think science journalism would be booming–yet nothing could be further from the case. If you watch 5 hours of cable news today, expect to see just 1 minute devoted to science and technology. From 1989-2005, meanwhile, the number of major newspapers featuring weekly science sections shrank from 95 to 34. Epitomizing the current decline is longtime New York Times science writer Andrew Revkin, who recently left the paper for a career in academia. In this conversation with host Chris Mooney, Revkin discusses the uncertain future of his field, the perils of the science blogosphere, his battles with climate blogger Joe Romm, and what it’s like (no joke) to have Rush Limbaugh suggest that you kill yourself. Moving on to the topics he’s covered for over a decade, Revkin also addresses the problem of population growth, the long-range risks that our minds just aren’t trained to think about, and the likely worsening of earthquake and other catastrophes as more people pack into vulnerable places. Andrew Revkin was the science and environment reporter for the New York Times from 1995 through 2009. During the 2000s, he broke numerous front page stories about how the Bush administration was suppressing science, and launched the highly popular blog Dot Earth. But last year, Revkin announced he was leaving the Times. He accepted a post as a senior fellow of environmental understanding at Pace University in White Plains, New York, where he will focus on teaching and two new book projects–complementing existing works like The North Pole Was Here, a book about the vanishing Arctic aimed at middle and high schoolers. In his new life, Andy will also have much more time to play with what he dubs his "rustic-rootsy" band, Uncle Wade. |