Since 1947, when a shepherd searching caves near the Dead Sea discovered fragments of ancient texts, scholars have sought ways to study the remarkable discovery — now known as the Dead Sea Scrolls — without damaging the 2,000-year-old documents. That quest continued in St. Paul on Tuesday when delegates from the Israel Antiquities Authority tested a new digital infrared camera system at the Science Museum of Minnesota.

Images in different wavelengths

In a secured and climate-controlled room at the museum, Tania Treiger used her gloved hands and assorted instruments to carefully arrange fragments of the priceless scrolls under an overhead camera. She is a conservator from Israel, one of only three people in the world who are trained and authorized to handle the ancient documents.

When the fragments were ready, overhead lights went out. Equipment beeped. Lights flickered in eerie shades. More beeps. Lights on.

Images of the fragment had been captured in 11 different wavelengths — some for reproductions in the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visible to humans and some in the infrared, said Gregory Bearman.

Bearman, a former scientist for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, has pioneered the application of imaging techniques used to observe objects in space to the study of archeological artifacts. He had arranged for a company called MegaVision to demonstrate its new imaging system for possible use with the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Within seconds of the shoot of this particular set of scroll fragments, a series of images appeared on a laptop screen.

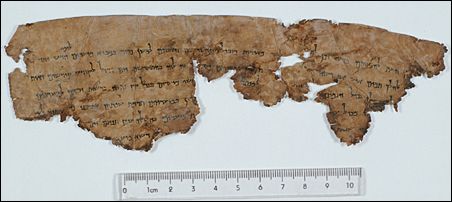

One was the view I could see with my naked eye: blurred markings on weathered chunks that resembled swatches from a very old leather jacket. There is no question the centuries have taken their toll on the scrolls — for example, the contrast between the parchment and the ink had deteriorated to the point where there was little text to see.

Next, the computer worked up the infrared images of the same fragments. Like magic, the original words began to appear as though someone had written them yesterday.

"That’s beautiful," said one of the researchers gathered around the work table.

Monitoring the scrolls comes first

The imaging, which was to continue today at the museum, is a pilot test of a large-scale project being considered for the scrolls, said Pnina Shor, Curator & Head of Dead Sea Scrolls Projects for the Israel Antiquities Authority. She arrived in St. Paul on Sunday to observe the tests this week.

The project’s No. 1 goal is to step up monitoring of the scrolls for any further deterioration, Shor said.

"The main concern of the Israel Antiquities Authority is to preserve these precious manuscripts for generations to come," she said. "We must make sure we are not causing any damage."

The scrolls contain the earliest known copies of religious texts that are revered by Jews and Christians alike — including nearly every book of the Hebrew Bible, known to Christians as the Old Testament. The writers who scribed them were contemporaries of Jesus of Nazareth.

Beyond religion, of course, they have monumental cultural and historic significance. And the Antiquities Authority has been under immense pressure to make them more readily available for research and for viewing by the general public too.

For centuries, the arid climate of the Dead Sea area helped preserve the scrolls. But after they were moved to Jerusalem beginning in 1947, they started to deteriorate.

People handling them made some initial mistakes, including using transparent sticky tape to join fragments and seal cracks, according to the website of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

In 1991, the Authority set up a climate-controlled storeroom and laboratory for the scrolls and began the painstaking process of restoring the fragments and detailing their contents. Eventually, the fragments were sewn between two layers of polyester net stretched in acid-free mounts. Those, in turn, were enclosed in a frame made of polycarbonate plates.

So housed, the scrolls were ready to share with the world, including the thousands of people who have lined up at the Science Museum of Minnesota to view them.

The scrolls were photographed in the 1950s. And the texts of most of the scrolls also have been published, although controversy persists over the exact meanings of difficult-to-decipher documents. Images of the scrolls also have been made available online.

Despite the precautions, the deterioration continues.

Now the hope is that this new state-of-the-art imaging system will help strike a balance between preserving the documents and also making high resolution color and infrared images of them available for research.

"With this imaging, there could be a lot more for the scholarly world to see," Shor said.

Meanwhile, the full array of images could form a basis for detecting even subtle damage. Images from the visible part of the spectrum could, for example, reveal changes in color. And those from narrow bands in the infrared could show other changes in more detail than could be seen with the naked eye.

Why conduct the tests in St. Paul? It’s simple. The scrolls were here, she said.

You can learn more about the Science Museum’s exhibit here. And you can see a complete list of scrolls in the exhibit and their translations here.

(end of article)

return to list of publications