Sharon Schmickle

Sharon Schmickle covers national and international stories for the Minneapolis Star Tribune. Her recent assignments have taken her to Iraq, Afghanistan, Egypt, Pakistan, Kuwait, Thailand, and the UK. Before 2003, she worked in the Star Tribune's Minneapolis newsroom as a science writer and in its Washington Bureau as a Capitol Hill and political reporter. She has won top awards from the National Press Club, the Overseas Press Club, the Society of Professional Journalists, and the Associated Press. She was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 1996.

| Article |

Young Somali Immigrant Appreciates Life PELICAN RAPIDS, Minn. — Abdirashid Nuur was lucky he arrived in Minnesota during the month of August. He had enough adjustments confronting him without the daunting distraction of a Northern Minnesota winter. Abdi (as his friends call him) had boarded a plane in Kenya's Nairobi – a sprawling metropolis of more than 3 million people. It's a subtropical city teeming to the pulse of hip-hop and Benga music, where glittering malls and gritty street hustlers operate side by side, thousands fill the stands for major league soccer and the cops never seem to get ahead of the robbers. His destination was Pelican Rapids, a two-stoplight town of 2,500 people where farm fields roll right up to the commercial district. The culture throbs here, too, but with a far different rhythm and flavor, reflecting civic interests of Northern European immigrant settlers: quilt shows, library projects, festivals in the parks and high school sports. The police department's website lists seven officers on the force. "I couldn't believe this was such a small city," Abdi said. This is where we liveIt was not the America he had seen in movies, which typically were set in New York, Washington, D.C., or Los Angeles. But it was the place where a brother had landed when he made it to the United States ahead of the rest of the family. "My brother said, 'This is where we are going to live for the rest of our lives,' " Abdi recalled. One of the first "American" foods Abdi tasted was pizza. What else? "I didn't like it," he said. But that was nearly four years ago. Now, he has acquired a taste for pizza – and, more profoundly, an appreciation for peaceful Pelican Rapids. "I live freely, here," he said. "Life is much better. ... I like small cities. There is less trouble." From Mogadishu to uffdaHis then-now comparisons reach beyond Nairobi to Somalia, where Abdi was born in Mogadishu, the capital city, and spent the first year of his life. His family fled the violence of that failed state and lived in refugee camps in Kenya before making it to Nairobi. Abdi had learned English in the refugee camps. But it was British English spoken with a Somali accent, and he initially struggled to make himself understood in Minnesota. "I could understand what people were saying, but they could not determine what I was saying," he said. That has changed in four years so that he sounds very much like other Minnesotans. Indeed, he's learned the word uffda – although he doesn't use it on a regular basis. "I always heard people saying that word," he said. "I think it is from Norwegian or something." What stood out about Abdi during our interview was not his accent. It was his politeness and formality. He wore a crisp dress shirt and a tie to our interview at the Lutheran Social Services Refugee Center. His dark eyes focused intensely while I asked questions, and he carefully thought through his answers before uttering a word. |

| Article |

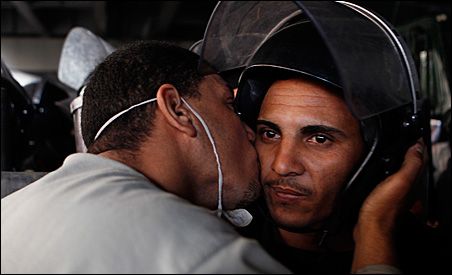

In Egypt's Secret Military Lies a Cautionary Tale By kicking aside its president, dissolving its parliament and suspending its constitution, Egypt has wiped clean the slate of its government. Maybe. There is a different slate in this potentially pivotal Arab nation — written largely in invisible chalk. Experts know just enough to read in it a cautionary tale. The military authorities who have taken control of Egypt have operated largely in secret to build their own empire of money and power. "You have this huge beast of a thing in all sectors of Egypt's economic activity," said Robert Springborg, a Minnesota native whose extensive experience in the Middle East includes working as director of the American Research Center in Egypt. Currently he is a professor in the Department of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif. And Egypt is taking a long-shot gamble by trusting that commanders of such immense power and wealth eventually will relinquish meaningful control to civilians, say Springborg and other experts. Even the Egyptian people do not know the full extent of the economic and political force their military leaders have amassed. No one does outside elite circles in Egypt because that force has been assembled over decades behind the veils of political expediency and national security. Origins of a secret empireThe origins of this secret military economy go back before Egypt's now-deposed President Hosni Mubarak began his authoritarian rule some 30 years ago. After World War II, Egypt asserted itself in the global expansion of military-industrial enterprise. It became the leading Arab manufacturer of aircraft and weapons. It set up a series of state-owned enterprises under the control of an Armament Authority commanded by a major general, according to Global Security.org. Its customers included the United States, European nations and neighboring Arab states. Because Egypt considered the value of its military exports confidential, it omitted this information from its published trade statistics. It outlawed news coverage of the military enterprises. And it defied efforts by global financial institutions like the World Bank to lift the curtain of secrecy and bring the military-run factories into the private sector where they would be more visible and accountable. You have to go back to the 1980s to find estimates on the exports from this hidden industry. And those estimates range from $70 million a year in 1980s dollars to $1 billion. |

| Article |

Behind the Turmoil in EgyptAngry young people who expected more  The man who served my first cup of steaming mint tea in Cairo hadn't wanted to be waiting tables and setting up hookahs at age 26. He'd gone to a technical school, planning to land a construction job that would pay enough to get married and support his household while also helping his mother, a widow. Instead, he had drained his family's savings and lost hope of ever earning enough to support a wife and children. You find similar stories everywhere in the Arab countries. The faces of the Arab protestors on television over the weekend are the faces of frustrated young people I saw a few years ago stuck in menial work throughout the region — leading donkeys through crowded markets, balancing trays piled with bread on their heads and peddling newspapers from sidewalk stands. They were working, but just barely. And they were consumed by resentment. The rage exploding on the streets of Egypt, Yemen and other Arab countries has been boiling under the surface for a long time. The leaders of those countries should have seen it coming. Professor Ragui Assaad is one of many experts who have warned for years that young Arabs were frustrated to an explosive point. "What is fueling all of this anger is the dashed expectations of the young people who are a larger and larger portion of the population of the region," said Assaad, an economist at the University of Minnesota's Humphrey Institute. Assaad spent two recent years in Cairo working to document rising frustration among youth across the Arab world. Some of his findings are reported in the book "Generation in Waiting: the unfulfilled promise of young people in the Middle East." [PDF] His reports also can be found on the website of the Middle East Youth Initiative, a project of the Brookings Institution and the Dubai School of Government. Youth bulgeHere's the root of the problem, as Assaad explained it to me: The Arab world had its own version of a baby boom starting some 25 years ago. It gave rise to the largest generation in the history of the region, more than 100 million young people. As a result, the median age is 24 in Egypt and 18 in Yemen compared with 37 in the United States and 44 in Germany, according to the CIA World Factbook. The Arab countries weren't nimble enough to expand their school systems, health clinics and other facilities to meet the needs of this youth bulge. So masses of these kids overcrowded the available schools and got diplomas without real educations and skills that could help land jobs. |

| Broadcast |

How Much Should Science Accommodate Religion Find a public debate about the intersection of science and religion and you also can expect to find PZ Myers, a biology professor at the University of Minnesota Morris. This month, Myers debated author Chris Mooney over questions of how far science should go to accommodate religion and whether those who champion science must oppose faith. The debate, reported by Discover Magazine, came at a conference of the Council for Secular Humanism in Los Angeles. It continued in a special episode of Point of Inquiry, a podcast sponsored by the Center for Inquiry, where Mooney is one of three hosts. It’s no surprise that Myers was unyielding. He has been associated with the movement called New Atheism in which authors such as Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens argue that many religious claims — including the virgin birth of Jesus — are scientific in nature and thus, like other hypotheses, can be tested and proven false. "Talking about accommodating ourselves to others’ ideas is fine in a political and diplomatic sense, but there are core issues that we are not going compromise on," he said. "Foremost, we think religion is false." But Myers allowed some room for framing certain relevant conversations. "I’ve talked to fundamentalists, and often one big issue is they want to send their kids to college, they want them to succeed in this economy, and they feel really, really frightened by the fact that they’ll go off to college and be converted to godless atheists," he said. "What I will say to them is I am not going to compromise. I am an atheist. But when I teach classes....I’m too busy teaching biology to talk about this other stuff." Mooney also is a self-described atheist and a critic of science illiteracy. He is the author of three books: The Republican War on Science, Storm World, and Unscientific America. But he differs considerably from Myers in that he argues for accommodation, or accepting a place for religious faith in scientific inquiry. Religion is vastly diverse across America, Mooney argued. And many faiths allow varying degrees of compatibility with science. "You will have actual Christians who, nevertheless, are supportive of the teaching of evolution, embryonic stem cell research and all of the rest," he said. "There are Christian ministers who certainly have Christian beliefs [who] say evolution is good science and it’s OK to have this....What do we do with them?" |

| Article |

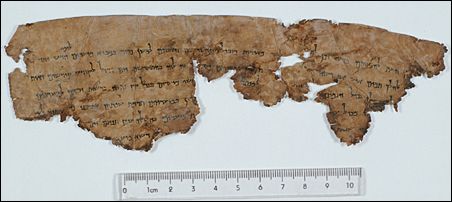

High-Tech Test of Dead Sea ScrollsUnder way at Science Museum of Minnesota  Since 1947, when a shepherd searching caves near the Dead Sea discovered fragments of ancient texts, scholars have sought ways to study the remarkable discovery — now known as the Dead Sea Scrolls — without damaging the 2,000-year-old documents. That quest continued in St. Paul on Tuesday when delegates from the Israel Antiquities Authority tested a new digital infrared camera system at the Science Museum of Minnesota. Images in different wavelengthsIn a secured and climate-controlled room at the museum, Tania Treiger used her gloved hands and assorted instruments to carefully arrange fragments of the priceless scrolls under an overhead camera. She is a conservator from Israel, one of only three people in the world who are trained and authorized to handle the ancient documents. When the fragments were ready, overhead lights went out. Equipment beeped. Lights flickered in eerie shades. More beeps. Lights on. Images of the fragment had been captured in 11 different wavelengths — some for reproductions in the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visible to humans and some in the infrared, said Gregory Bearman. Bearman, a former scientist for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, has pioneered the application of imaging techniques used to observe objects in space to the study of archeological artifacts. He had arranged for a company called MegaVision to demonstrate its new imaging system for possible use with the Dead Sea Scrolls. |

| Article |

Scientists Monitor Fragile Glaciers in Real TimeUsing satellite images and email  When cracks appeared this month on one of Greenland’s largest glaciers, the Jakobshavn Isbrae, scientists in Minnesota and Ohio were watching with the help of new tools that come at a crucial time for monitoring such changes around the globe. It looks like a rift could be opening deep into the glacier, Ian Howat of Ohio State University wrote in a quick email to Paul Morin at the University of Minnesota. Morin agreed. The satellite image they had just received was something of a red flag, signaling that a large break in the far-away glacier might be imminent. So Morin alerted NASA, a sponsor of their research. "We sent emails back and forth," Howat said. "While that was taking place...the next satellite image came in — and, boom, here we go — it actually had happened!" An ice chunk roughly one-eighth the size of Manhattan Island in New York had cracked away from the glacier. It was the first time scientists had been able to see a break of that magnitude coming and then watch it happen in something very close to real time. This stepped-up glacier watching is part of a new program at the U of M’s Antarctic Geospatial Information Center, where Morin is the director, and at Byrd Polar Research Center at Ohio State. It comes at a time when scientists have urgent reasons to closely monitor glaciers and polar regions. Among other reasons, they are watching for events that could lead to rising oceans and other effects related to global warming. |

| Column |

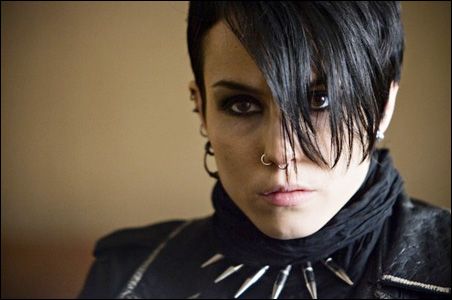

Why You Don't Want the Dragon-Tattooed Lady's Photographic Memory In one of Stieg Larsson’s popular novels, Lisbeth Salander deploys her photographic memory to master a heavy mathematical tome. The dragon-tattooed Swedish Superwoman breezes through Pythagoras’ equation (x2 + y2 = z2) and centuries of other mathematical challenges to confront the perplexing last theorem of Pierre de Fermat. Whew! For most of us non-fictional characters, memory doesn’t work that way. And you wouldn’t want photographic memory if you read Anthony Greene’s fascinating report in the July/August issue of Scientific American Mind. Greene is a psychology professor at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. "Many people wish their memory worked like a video recording," Greene says. "How handy would that be? Finding your car keys would simply be a matter of zipping back to the last time you had them and hitting ‘play.’ You would never miss an appointment or forget to pay a bill. You would remember everyone’s birthday. You would ace every exam." So you might think. In fact, living with true photographic recall — known clinically as Eidetic memory — could be like confronting all of the information in cyberspace without the benefit of Google or any other aid for searching, sorting and organizing. "It would not let you prioritize or create the links between events that give them meaning," Greene says.All about connectionsDuring the 20th Century, scientists established that a memory is not at all like a tidy file in an organized cabinet. Instead, memories are dispersed across regions of the brain that are responsible for language, vision, hearing, emotion and other functions. "Our brain has evolved not just for learning and memory but for the management of relations: past, present and future," Greene said. "The ability to form and retain connections gives us not just a record of events but also the foundations of comprehension." Those management networks are physically supported by neurons as they connect to and communicate with other neurons. |

| Column |

Ignorance of ScienceWho's to blame?  If the American public doesn’t "get" science issues, who is to blame — the many scientifically illiterate Americans or scientists themselves? My Facebook friends were atwitter (no social media mixups intended here) with that question on Sunday in response to a Washington Post piece by science journalist Chris Mooney. He is the co-author, with Sheril Kirshenbaum, of "Unscientific America: How Scientific Illiteracy Threatens Our Future." Ignorance of science is not the whole explanation for the mismatch between public opinion and scientific evidence on evolution, vaccinations, climate change and many other issues, Mooney asserts. "As much as the public misunderstands science, scientists misunderstand the public," he says. "In particular, they often fail to realize that a more scientifically informed public is not necessarily a public that will more frequently side with scientists." On climate change, for example, the gap between scientists and a good share of the public may not be due to a lack of information — but, instead, to deep-seated political loyalties, to the reality that politics trumps science on some issues. "The battle over global warming has raged for more than a decade, with experts still stunned by the willingness of their political opponents to distort scientific conclusions," Mooney wrote. "They conclude, not illogically, that they're dealing with a problem of misinformation or downright ignorance — one that can be fixed only by setting the record straight." |

| Article |

Human Genome Project: 10 Years LaterAlthough effort draws a shrug from some, Mayo and U of M experts thrilled by 'genetic revolution' gains  First of two articles Ten years ago, world leaders hailed the deciphering of the human genome as the kickoff for a revolution in the treatment of human diseases. You can be forgiven if the anniversary slipped your notice. It's largely been marked with a shrug. If you look for celebration, you can find it, though. Just visit genetics laboratories at the Mayo Clinic and the University of Minnesota. There, scientists still use the word "revolution" 10 years after that first sequence was released in rough draft form on June 26, 2000. "This has totally revolutionized the way we think about genetic experiments," said Michael O'Connor, who heads the Department of Genetics, Cell Biology and Development at the University of Minnesota. "We do things by genome sequencing now that we wouldn't have dreamed of 10 years ago," said professor Harry Orr, who specializes at the U of M in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's. "Technology development has just skyrocketed," Orr said. "You know how the space program is credited for various aspects of computer development and electronics and so forth? We've seen a similar stimulus of genetic technology." Buried in dataBut the researchers also express humility. A daunting amount of information is packed into our tiny cells. It's one reason this revolution has yet to sweep through your local clinic. The lag between the laboratory and the clinic illustrates the No. 1 lesson from a decade of research: Despite centuries of medical and biological advances, we knew shockingly little about our own bodies — about how they develop from a cell to a creature complex enough to invent a computer, grow a malignant tumor, hit a home run and love a child with heart-aching intensity. |

| Article |

Allegations about CIA Interrogations Raise Medical-Ethics Questions Chilling new allegations came out this month in connection with the CIA's interrogations of suspected terrorists: the group Physicians for Human Rights reported evidence that medical professionals conducted illegal human research and experimentation on detainees in U.S. custody. Now, the Minneapolis-based Center for Victims of Torture has joined human rights groups in filing a formal complaint against the CIA. The groups are calling for a federal investigation. "Essentially there has been no investigation ordered by a president, there has been no public accounting of what happened, how it happened and why it happened," said Douglas Johnson, the Center's executive director. "There's been no public tracing through of the decisions — where they went wrong, why they went wrong and what we learned from this situation in order to make sure it doesn't happen again." The new physicians' report indicates that medical experts working for the CIA "performed research on how to psychologically break prisoners and on how to use physically harmful forms of torture including waterboarding," Dr. Steven Miles, a Center board member, said in a statement. Miles, author of the book "Oath Betrayed: America's Torture Doctors," was one of the first U.S. physicians to object publicly to the role that doctors, psychologists and medics played in the CIA interrogations. He also is a professor at the University of Minnesota's Center for Bioethics. In response to this latest development, Miles said: "These health professionals violated laws and medical ethics pertaining to the use of prisoners as research subjects dating back to Nuremburg and ratified by every U.S. administration since then." The CIA denied the allegations in an e-mail to MinnPost. "The report's just wrong," said George Little of the CIA's Office of Public Affairs. "The CIA did not, as part of its past detention program, conduct human subject research on any detainee or group of detainees. The entire detention effort has been the subject of multiple, comprehensive reviews within our government, including by the Department of Justice." Medical monitoring vs. illegal researchIn the months following the 9/11 attacks, Bush administration lawyers at the Justice Department helped redefine interrogation practices such as waterboarding, sleep deprivation, enforced nudity, temperature extremes and prolonged isolation. They established legal thresholds for such "enhanced interrogation." And they enlisted medical monitors to ensure that detainees were not pushed over the newly defined thresholds of illegal torture. That much had been widely reported. And it was a subject of intense controversy even before the International Committee of the Red Cross reported [PDF] in 2007 that the medical experts had participated in ill-treatment of 14 detainees by working to "serve the interrogation process, not their patients." |

| Column |

Reviving Rural MinnesotaSome small towns with big ideas--immigration, sprucing up, co-oping  But here's the lament we shared during the breaks: It's no longer true that everyone living in urban Minnesota has ties to rural Minnesota — has a grandmother or an uncle living on a farm where city kids can learn to collect warm eggs in the chicken coop and watch the miracle of birth in the barn. Sure, we celebrate our rural cultural heritage at the State Fair every summer. And we indulge our need for a collective memory with the pretense of life in the prairie town of Garrison Keillor's fantasy. The truth is, though, that to maintain a cohesive culture and an economy that can thrive statewide, we have to work at it. That's what drew more than 200 people to University of Minnesota Morris campus for the Symposium on Small Towns & Rural-Urban Gathering. Century of lossEveryone there knew the history lesson: In 1900, two of every three Minnesotans lived in a rural area, most of them on farms. In 2000, three in four Minnesotans lived in an urban area. And only 3 percent lived on a farm. Young people led the exodus. And the towns they left behind gradually aged to the point where deaths outnumbered births each year. The survivors were far more likely to be poor. Minnesota ranked among the nation's highest income states in 2000 with per-capita earnings of $23,198. Taken alone, though, Minnesota's rural cities would have ranked near the bottom with a per-capita income of $17,880, according to a report [PDF] by the Center for Small Towns on the Morris campus. If you are reading this article on a computer in a metro area, you may say "So what?" When I think about the answer, I think about the argument we made over the years for empowering women in the workplace: A society can't reach its full economic potential if half of its workforce is under-employed. In the same sense, a state is squandering a good portion of its economic power if one-fourth of its people lack opportunities to thrive. Spiffing up, fighting and leveragingThe big take-away message from the symposium was that some small cities and towns aren't sitting back waiting to die. Some are spiffing up to serve as bedroom communities where workers in regional centers can buy more housing for less money and raise their kids in that idyllic setting of Minnesota Past. Some see a future in telecommuting, and they are fighting for access to broadband networks that can free up workers to live in scattered locations. Some are leveraging resources to rebuild everything from cultural amenities to small-scale energy projects to home-grown food markets. |

| Column |

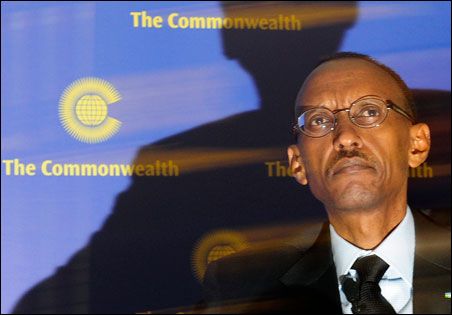

Fierce Fight Over Record of Rwandan Genocide Search the Internet, and you'll find a wealth of sites lauding Paul Kagame as the president who led Rwanda to achieve one of Africa's most remarkable success stories. You also will find news reports characterizing Peter Erlinder, the William Mitchell law professor, as a passionate and effective champion for the underdog and the outcast. There is truth in both characterizations. But there is much more to say. Erlinder's arrest in Kagame's country last week opens doors to a world of intrigue and suspicion in which the Minnesota lawyer and the former rebel leader are locked in a fierce struggle over the historical record of the Rwandan genocide. Erlinder has been bent for years not only on implicating Kagame but also on exposing what he calls a cover-up by the U.S. Pentagon of the true story behind the genocide in which some 800,000 people were slaughtered. For his part, Kagame — even while he took bows on international stages — was alarming the U.S. State Department with a harsh crackdown on alternate versions of what was behind his country's bloodbath. The context for their clash is as complicated as a story can be — too complicated to report in a single news article. But Erlinder's case illustrates important parts of it. "This case gives us a window to see what is going on in Rwanda," said Michelle Garnett McKenzie, an attorney with Advocates for Human Rights in Minneapolis who has worked to help reconcile post-war conflicts in other parts of Africa. So let's look into the window. |

| Column |

Genetic Research:What are the risks of terrorism or accidents?  At high school graduation parties recently, other parents were eager to quiz Jeffrey Kahn about news of the first man-made genome — the first living, reproducing creature to be born not of a natural parent but rather of a computerized plan for assembling strings of DNA. Could scientists construct bacteria that would clean up oil, asked a parent who obviously had in mind the disastrous BP spill. Others asked about tailoring creatures to manufacture life-saving drugs. No one asked the question that bothers Kahn, the director of the University of Minnesota's Center for Bioethics: Could somebody forge the genome for, say, smallpox? "No one went there," Kahn said. We should go there. Most of the public concern over this latest product of genetic laboratories has focused on moral questions of whether scientists were usurping the prerogative of the gods by seeking to create life from scratch. That is an important focus. But in an age when students can tinker with DNA in their basements — assembling and breaking down the building blocks of life as if they were so many Legos — we also need more serious conversations about the risks that could arise through malicious intent or innocent accident. Ordering up the ingredients for lifeThe parents at those graduation parties were reacting to the latest breakthrough in the fast-moving field of synthetic biology: Researchers at the J. Craig Venter Institute synthesized a bacterial genome to create the first man-made cell that was capable of reproducing. (MinnPost's report is here.) Venter Institute scientists said they used computers to design their creation and identify 1,078 specific "cassettes of DNA" they would need to build it. They then ordered the cassettes from DNA suppliers that routinely fill such orders around the world. The suppliers draw from the four chemicals signifying DNA's alphabet — A, C, T and G — and use micro-plumbing to connect them in the desired sequences. Researchers use such ordered-up sequences for a wealth of legitimate projects. In Minnesota, one group is engineering bacteria to function as microprocessors which could help detect cancer and other diseases. Other Minnesota researchers have transformed bacteria and yeast molecules into tiny factories that put out the ingredients for healing drugs, nutritional supplements and cheap biofuels. Until recently, scientists who ordered such designer DNA "all were sitting in universities or large research labs where they were subject to stringent rules," Khan said. But with the explosion in genetic research, even high school and college students were able to shop online and order the tools for tinkering with life. |

| Column |

Chimps Clearly React to Offsprings' DeathsAre they grieving?  Details of the study are heart wrenching: A chimpanzee called Jire carried the corpse of her infant for some 27 days after the small chimp died in the forests surrounding Bossou, Guinea. She groomed the little body, cuddled it in her nests and objected to any separation from it. The poignant story is not unique. A research team led by Dora Biro of Oxford University in England reports in Current Biology observing two other chimp mothers stubbornly carrying the remains of their lifeless offspring for up to 68 days — even while the bodies stank with decay and eventually mummified. Were these animals — our close evolutionary cousins — grieving in human fashion? That is the fascinating question raised by this report and one other in the same journal. Professor Michael Wilson of the University of Minnesota is among experts who caution us not to anthropomorphize about other species, not to project our own natures on them. Wilson is one of several U of M scientists who have studied chimps extensively in Tanzania’s Gombe National Park, where primatologist Jane Goodall began documenting chimp behavior in the 1960s.Too short vs. too longWilson was not part of the Oxford research team reporting these latest observations of chimp mothers. But the findings didn’t surprise him. "I've spent much more of my time than I would like watching dead and dying chimpanzees, and the responses of mothers and others to them," Wilson told MinnPost. "It's fairly common for chimpanzees, as well as various other primates, including baboons and rhesus monkeys, to carry their infants long after they've died." So the behavior is well established. What remains in doubt is the question of what it means. Are these caring mothers expressing grief as we understand it? There could be other explanations, Wilson said. Reproduction is a powerful evolutionary force for survival of a species. That force can extend to care of the offspring at least until they are able to reproduce on their own. |

| Article |

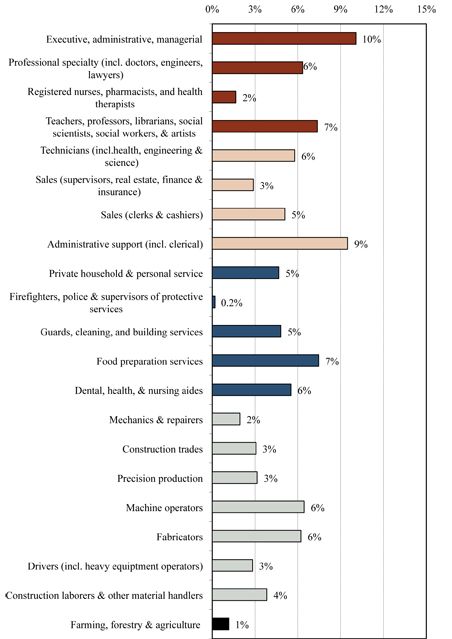

Census Analysis Pierces Stereotype:48% of Twin Cities' immigrants hold white-collar jobs.  Take a minute to think about the immigrants working in the Twin Cities. What comes to mind? Janitors? Maybe meat processors? How about taxi drivers? Thousands of immigrants in our midst do such work. But this may surprise you: Nearly half of the immigrants working in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area hold white-collar jobs — doctor, teacher, engineer and business executive, for example. And contrary to the stereotype of the needy immigrant, they take home relatively high wages, according to new analysis of census data by the Fiscal Policy Institute in New York. [PDF] The full reality of immigration and its economic impact gets lost in fiery rhetoric over issues like border fences and amnesty. But now, with immigration reform looming as one of the next big challenges facing Congress, the stakes are too high to allow the debate to be hijacked for the sake of hot-button issues alone. That's true even for a northern state like Minnesota. And high-skilled immigrants may be a key to closing partisan gaps in the debate. A growing, educated and skilled presenceMore than 10 percent of the workers in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area between 2006 and 2008 were foreign born — up from 3 percent in 1990, according to the Fiscal Policy Institute's data. Fifty-seven percent of the immigrants had taken at least some college courses. While 48 percent had professional and administrative jobs, just 27 percent did blue collar work, and 23 percent held service jobs. A similar pattern held across 14 of the nation's 25 largest metro areas analyzed by the institute's researchers. A few cities stood out prominently as home to immigrants doing white-collar work. In Pittsburgh, for example, three-fourths of the immigrants worked in professional and administrative jobs while just 11 percent were blue collar workers. The pattern was different in Dallas, Denver and a few other cities where close to two-thirds of the immigrants did blue-collar or service work. One reason is that booming economies in those cities attract more recently arriving immigrants. But the nation as a whole — like the Twin Cities — gives a far different picture from what you would expect from political debates in which immigrants often are cast as poor, struggling to hold on at the margins of the workforce. "The impression that sometimes emerges in public discussions is that immigrants are primarily working in low-skilled jobs, but this broad overview shows that this is far from the case," said the authors of the report. Even some illegal immigrants sit in professional offices. While workers who are here illegally were far less likely to hold higher-wage jobs, the report cited data from the Pew Research Center showing that about one in five illegal immigrants do white-collar work. |

| Column |

Altering Food-Crop Genes:Old issue with new concerns  The global uproar over fiddling with genes in food crops has quieted as millions of people ate products made from genetically engineered corn, soybeans and other plants with no apparent ill effects. But the assessment of the crops’ impacts on the environment and on farmers is far from over. A comprehensive report released today by the National Research Council shows why it’s important to continue monitoring the technology that overwhelmingly dominates Minnesota’s farm fields. What’s no longer in question is whether farmers would accept the high-tech varieties that first were commercialized in 1996. Last year, 92 percent of all the soybeans grown in Minnesota carried genes added to help control weeds. Corn was close behind: 88 percent of the Minnesota crop contained genes to help farmers fight insects or weeds or both. "Not since the introduction of hybrid corn seed have we witnessed such a sweeping technological change in U.S. agriculture," said the report compiled by a committee of the Research Council’s Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources. Nationwide, almost half of the land for everything farmers grow is planted to engineered crops — primarily cotton, corn and soybeans. The reasons for the rapid switch to the new technology are many. GE crops take a good share of the guesswork out of farming. They help protect yields, reduce the danger of handling harsh pesticides and save farmers money even though they have to pay a "technology fee" for the GE seed. As for consumers, they have pretty much accepted so-called GMOs with some notable exceptions discussed later in this article. Still, consumers and farmers alike have reason to heed concerns raised in the report. |

| Column |

Cambodia Temple Ruins Spur Wider Question:Are there time limits to the greatness of a nation?  SIEM REAP, CAMBODIA — "Welcome to the Angelina Jolie temple," our guide said as we climbed stone steps toward Ta Prohm, one of the most beautifully eerie sites in Cambodia's ancient Angkor ruins. I felt a stab of sadness. Not because the jungle was winning its battle with the 800-year-old temple. Yes, the massive roots of strangler-fig and silk-cotton trees were spectacularly crushing the temple's intricately carved corridors and pillars. What saddened me was his eagerness to define this amazing icon of his once-great country by deferring to American pop culture. To be sure, he could have done worse than to associate Ta Prohm with the actress-humanitarian who visited here to shoot the 2001 adventure film "Lara Croft: Tomb Raider." But this ancient wreck of a temple was the work of the mighty Khmer empire that once controlled vast reaches of Southeast Asia. It deserved respect in its own right. Here and everywhere else in Cambodia, I couldn't stop thinking about how and why great civilizations have failed. The questions had puzzled me before I left Minnesota in February. And they've hounded me since my return. Was Jared Diamond correct when he said in his book "Collapse" that societies fail because they inadvertently choose to do so? Losing its mojo?One reason the question nags is that so many Americans have lost confidence in their own prominence and prosperity. We're surrounded these days by headlines like the one in Newsweek a few months ago: "Is America losing its mojo?" We still pile up the Nobel prizes (won mostly by American scientists in their 70s, Newsweek noted). Look deeper, though, and it's clear that America "is like a star that still looks bright in the farthest reaches of the universe but has burned out at the core," Newsweek said. One of many points it offered in support of that statement came from a study [PDF] last year by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation in Washington. It analyzed 40 countries on various measures of what they were doing to make themselves more innovative in the future. The United States came in dead last. |

| Column |

Attack on CIA:'This was a victory for al-Qaida'  When a suicide bomber killed seven CIA employees operating from a secret base in Afghanistan, the news gave Americans a rare look into the spy agency's expanded role on the front lines against al-Qaida and its allies. It also prompted fresh debate over the military use of an agency that operates in shadows and secrecy. Afsheen John Radsan was assistant general counsel for the CIA during the tense years after Sept. 11, 2001. Now he directs the National Security Forum at William Mitchell College of Law in St. Paul. He took time to talk to MinnPost about the aftermath of the Dec. 30 bombing in Afghanistan. MP: Is this expanded use of the CIA sustainable? In other words, can that agency ramp up to face new terrorist fronts as they emerge in Yemen, Somalia and elsewhere?AJR: The CIA's role is crucial in countering terrorist groups, in going after al-Qaida. We would not be able to do this without a strong and effective CIA. . . . I agree that the CIA can't do everything. And it can't be everywhere. But what other agency would be able to carry out these functions? This is not the first time that we've ramped up the CIA's activities during a war. During the Vietnam War, we had many CIA officers in Indochina. MP: Maybe a better question is whether it should ramp up. The incident triggered fresh debate about empowering the CIA to play a larger role in military operations.AJR: More and more, some people will say that what the CIA is doing in Afghanistan and other places is closer to military activity. And then they conclude it should be folded into the Pentagon. That's a fair debate. . . . When you don't want to send in the Marines but you think the diplomats are insufficient, you need something in between. That's been the CIA. The America public should understand that the CIA as a collective, did not want to do all of these things after 9/11. There were people who said we should stick to our traditional intelligence-gathering function. . . . But after 9/11, the president looked around the room in his cabinet meetings at Camp David. He wanted people inside Afghanistan. And of all of the agencies, it was the CIA that could put people into place far sooner. |

| Article |

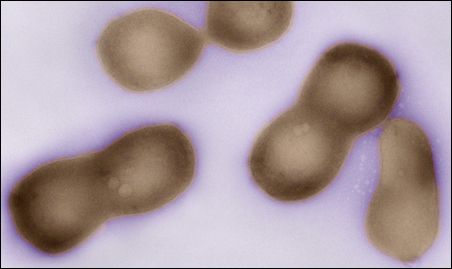

While Darwin Observed Evolution, Synthetic Biologists are Learning to Control ItThis is the third in an occasional series of articles we will run in this year that scientists have dubbed "The Year of Darwin."  Even with his celebrated skill for making meticulous observations of nature, Charles Darwin never could have seen anything like the E. coli glowing fluorescent green in a laboratory at the University of Minnesota. The natural forces of evolution Darwin described so famously 150 years ago did not craft these bacteria. Laboratory workers did. They took the basic parts list for life — DNA's four defining chemicals — and created a suite of genes that aren't naturally present in E. coli. The synthetic genes transformed the bacteria into living microprocessors, capable of the logic exercises you find on a silicon chip. Such are the products of an exciting and controversial scientific thrust called synthetic biology. Biologists are poised to take over evolution, diverting species from their natural Darwinian courses and turning them in directions scientists want them to take. Darwin observed evolution. Synthetic biologists are learning to control it — breaking down and reassembling life's basic parts as if they were so many Lego bricks on the floor on Christmas morning. In the process, they are amplifying debate over one of the most profound questions humans face: Is the world ours to make and transform as we wish? Ordering life by emailInstead of waiting for Darwinian evolution to produce useful mutations as it has for some 4 billion years, synthetic biologists |

| Article |

Darwin Still Influencing Religious Thinking in MinnesotaThis is the second in an occasional series of articles the MinnPost will run in this year that scientists have dubbed "The Year of Darwin."  Here's a news item you've probably never read or heard: The issue was evolution. It drew some 40 Christians to the Augsburg College campus in Minneapolis. But this was no protest. These Lutherans were celebrating the 150th anniversary of the publication of Charles Darwin's "On the Origin of the Species." Religious opposition to the theory of evolution has dominated America's headlines for so long that you could be forgiven for thinking that evolution forced stark choices for all people of all faiths: If Darwin was right, the scriptures must be wrong — or vice versa. If God created man in his own image, then humans couldn't have evolved in a process that led through swamps to apes to me writing this article on a tool created with dazzling human intelligence? The tradeoff never was that clear, though. While the spotlight focused on controversy, most people of faith were forming a far more nuanced understanding of how belief squares with Darwin's theory. And some actually embraced evolution. Take those Lutherans. Their Oct. 31 symposium was billed as a celebration of "our knowledge of the world — of God's creation — gained through science and evolutionary biology." Now comes the to be sure, inevitably essential in a report about anything as complex as religion. There are Lutherans — indeed, whole congregations of them — who reject Darwin's theory. |

| Article |

150 Years Later, 'Origin' is Both a Pillar of Science and a Still-Volatile SubjectThis is the first in an occasional series of articles we will run in this year that scientists have dubbed "The Year of Darwin."  Here's professor Sehoya Cotner's "Five Cent Tour of Human Evolution" in summary: Fossils, DNA and other evidence add up to the unassailable conclusion that humans gradually emerged more than 100,000 years ago as part of the great ape family. For many of the 200 students in Cotner's University of Minnesota biology class her "tour" was the first serious exposure to the subject, even though evolutionary theory is a foundation for biology and many other courses they should have prepared to study in college. "They didn't allow evolution to be taught in my high school because of the controversial issues," student Brandi Ziegler said after the class. It is 150 years ago today since Charles Darwin published "On the Origin of the Species," laying down a theory for understanding the intricacies of life on the planet. If Darwin could come back today and walk through laboratories and libraries in Minnesota alone, he surely would be amazed see the vast body of knowledge built upon that theory. Still, evolution remains so culturally volatile that many high-school teachers shy away from it, leaving students with major gaps in their understanding of basic science, according to research by Cotner and professor Randy Moore, another U of M biologist who has written books about evolution. Here are highlights from survey findings they reported in BioScience, a journal of the American Institute of Biological Sciences:

|

| Article |

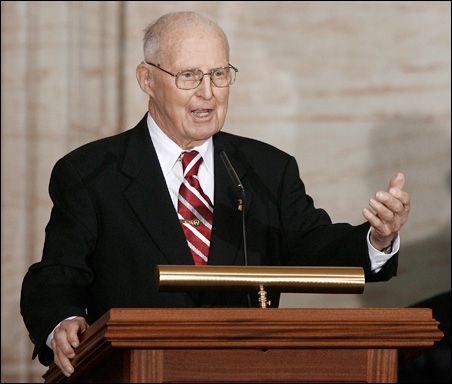

'Apostle of Wheat' Borlaug had deep Minnesota rootsNorman Borlaug, who died this weekend at age 95 in Texas, had deep Minnesota roots.  In the final days of a nearly three-year battle with lymphoma, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Norman Borlaug was asked by his daughter if he needed anything. The 95-year-old responded: "Africa. Africa. I have not finished my mission in Africa," his daughter, Jeanie Borlaug Laube, said Sunday from Dallas. Norman Borlaug, an Iowa farmboy who graduated from the University of Minnesota, believed food was a moral right. He traveled the world as a scientist and humanitarian, becoming the Green Revolution's "Apostle of Wheat" for the high-yield grain he perfected. Borlaug, who most recently had been a distinguished professor at Texas A&M; University, died Saturday at his Dallas home with his two children, five grandchildren and six great-grandchildren at his side. He was alert to the end, his daughter said. Thanks to Borlaug, families in Asia, Latin America and Africa have more to eat. When the National Academy of Sciences awarded him its Public Welfare Medal in 2002, academy President Bruce Alberts said, "Some credit him with saving more human lives than any other person in history.'' |

| Column |

Norman Borlaug: The Man Who Fed the WorldMy path crossed with 'The Man Who Fed the World' in wheat fields from Mexico to Kenya.  Decades before scientists discovered DNA's double-helix structure, plant breeders were unlocking genetic secrets in the major crops to relieve hunger worldwide. A giant among those pioneers was Norman Borlaug — the farm kid from Iowa who parlayed his degrees from the University of Minnesota into achievements that earned him the accolades "Father of the Green Revolution," Nobel laureate, winner of the Congressional Gold Medal, and, simply, "Grain Man." Borlaug died from complications of cancer Saturday night at his home in Dallas, said a spokeswoman for Texas A&M; University, where he was a distinguished professor of international agriculture. He was 95. "My good friend Norman Borlaug has accomplished more than any other one individual in history in the battle to end world hunger," former President Jimmy Carter said in the foreword to Borlaug's 2006 biography, "The Man Who Fed the World." I first met Borlaug in a wheat field near Obregon, Mexico, in 1991. I was traveling with a group of science writers who wanted to see first-hand the birthplace of the Green Revolution. It was the home of the breakthroughs that had helped India and Pakistan become self-sufficient in wheat and dramatically boosted yields in China, Latin American, Australia, Europe and the United States. Borlaug's face lit up when I identified myself as a reporter from Minneapolis. We had dinner together that night, and he spent hours in the field the next day relating his studies in Minnesota to the work that was to save hundreds of millions of people from starvation.

Failed the entrance exam but launched the missionBorlaug's name marks a building on the University of Minnesota's St. Paul campus where the young man from Cresco, Iowa, began his college education during the Great Depression of the '30s. I've often wondered whether it was the work ethic of that hardscrabble era or just old-fashioned Norwegian character that gave Borlaug immense pleasure in telling a self-deprecating story about his first months in Minnesota: He failed the University's entrance exam and thus had to start in what then was General College. |

| Column |

Why Detecting Nothing is Really Something in Gravitational-Wave Project Vuk Mandic and his colleagues made big headlines in scientific journals last week by finding nothing — nada, zilch, zippo — in their search for gravitational waves. In order to comprehend why nothing can be something big in astrophysics, we need to look first at the stakes in this quest for gravitational waves. These mysterious waves were predicted in Albert Einstein's 1916 general theory of relativity. If mass accelerates in some way -- say, you pick up a child or drive a car -- you have these ripples in space and time, the theory goes. But we Earthlings are mere specks on a universal scale, so any waves we make are insignificant. Instead, scientists are looking for the waves in connection with mega-scale cosmic events: collisions of black holes, shock waves from supernova explosions — and the granddaddy of all, the Big Bang. Influence has been observedThe gravitational waves' influence on stars has been observed. But the waves themselves never have been directly detected. If they were, it would set off a revolution in physics, opening an entirely new way of looking at the universe. "Black holes, we can't see at all at this point ... super nova explosions are not understood yet," Mandic said. "So we hope that gravitational waves would allow us to open another window into astronomy." Scientists also believe that the Big Bang created a flood of gravitational waves that still fill the universe and carry information about the immediate aftermath of that colossal explosion. No one has ever been able to study the full fiery nature of the physics at play in the moments following the Bang. In that sense, gravitational waves would have a unique tale to tell, Mandic said. |

| Column |

How Does Afghanistan Treat Women?Here's what I saw.  In western minds, the blue burqa stands as an icon for the oppression of Afghanistan's women because the Taliban forced women to wear the full body and face cover while they were in public. But the misery of millions of Afghan women goes far beyond the confines of the burqa, and it predates the Taliban rule a decade ago. Women and their supporters worldwide took heart after the Taliban were toppled in 2001 and the new government in Kabul declared a high priority on improving women's lives and rights. Girls went to school; their mothers, to work — most of them trading the burqa for the more traditional scarf draped loosely around their faces. Now comes news that Afghanistan's Parliament has passed a law forcing Taliban-style restrictions on women in Afghanistan's Shiite minority. The law reportedly would restrict when and how women could leave their homes. In the case of a divorce, it would grant child custody to the father. And it would force healthy women to have regular sex with their husbands — a provision denounced around the world as a sanction of marital rape. When I heard the news, I couldn't help but personalize it, remembering faces I had seen while reporting stories in that country in 2004. There were the tiny faces of baby girls in a hospital ward for malnourished children. Flies swarmed on the listless body of one six-month old girl who weighed just eight and a half pounds. The mother at her bedside was as gaunt as she was. Doctors explained why: When food was scarce it went first to the men and boys in a family, and the women all too often were too malnourished to produce milk for their babies. |

| Article |

Science News: Why Americans Know So Little Two years ago, when I was applying for a science journalism fellowship at England's University of Cambridge, my screening interview halted briefly after I dropped a comment that American newspapers were abandoning science coverage. Could that be possible in the United States — the world's capital of scientific discovery — wondered Sir Brian Heap, a prominent Cambridge biologist who was on the screening panel for the Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Fellowships. Oh yes, indeed, Americans on the panel told him sadly. The demise came even faster than those of us sitting around that table expected. As print journalism saw itself falling off a cliff, it pushed science coverage over the edge first. This week, the British journal Nature published an obituary of sorts, making some disturbing points about the implications for our knowledge about science. Before discussing the highlights, let's consider the context. Truth is that the United States never has been a wellspring of scientific knowledge, even given its great achievements in that regard. We wring our hands over low math and science test scores, but few adults bother themselves with the details. We get steamed over the politics of stem cells and global warming, but few voters know even the basics of cellular development and carbon emissions. One in four Americans surveyed in a recent test of scientific literacy did not correctly answer the question, "Does the Earth go around the Sun, or does the Sun go around the Earth?" Nearly half were wrong on the question of whether antibiotics can kill viruses as well as bacteria. Sixty percent could not say whether the North Pole marks an ice sheet on the Arctic Ocean. At the end of this article, you can test your own answers to the science literacy survey conducted in conjunction with the National Science Board's 2008 report on Science and Engineering Indicators. Dismal track recordThe point of my digression was to say that most Americans need all of the accessible science news they can get just to inform their own decisions about health care and science-based public policy. They still will be able to find it online — if they bother. But that is a big if, given the country's dismal track record. |

| Article |

Sudden NotorietyMosque in Minneapolis draws scrutiny from U.S. Senate, FBI and international media.  A news crew from Dubai arrived at the Abubakar As-Saddique Mosque as I was leaving on Tuesday. Al Jazeera, the Arabic news network, has booked an interview for next week, coming on the heels of reporters from dozens of other news organizations. The reporters were welcomed, but not the sudden notoriety that drew them to the Minneapolis mosque. Some Somalis say the mosque invited scrutiny and suspicion by helping to radicalize young Somali men for jihad in their homeland. Others say the mosque is a wrongly accused victim of the politics of war in East Africa. FBI investigators are saying nothing publicly about the accusations that have flown from the streets of Minneapolis to Capitol Hill and around the world. After listening to the arguments all week, I don't know what to say. So I'll simply tell you what I heard. On this much, everyone seems to agree: As many as 20 young Somali men have gone missing from Twin Cities homes during the past few months, some have called relatives to say they are in Somalia, one blew himself up in an apparent suicide bombing and the FBI is investigating alleged connections with Al-Shabaab, which the United States calls a terrorist organization. THE ACCUSATIONS Osman Ahmed turned rumor into sworn testimony (PDF) at a U.S. Senate hearing this month when he accused Abubakar's leaders of brainwashing the men and trying to scare their families from talking about their disappearance. Ahmed's nephew, Burhan Hassan, is one of the missing. The uncle was testifying on behalf of several families before the U. S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs. |

| Article |

Dispute over Muslim Women's HeadscarvesBill in Legislature Muslim women dressed in flowing headscarves have become a familiar image in Minnesota's human landscape even while debate flared elsewhere over head garb worn for the sake of Islam. Now a bill before the Minnesota Legislature shows that this state isn't immune to the global controversy. The bill makes no mention of any religion. Instead, it would require that the full head and face be shown on driver's license photos and state ID cards except for headwear needed in connection with medical treatments or deformities. It's a simple matter of public safety, the bill's chief author Rep. Steve Gottwalt, R-St. Cloud, told the St. Cloud Times. Law enforcement officials need unobstructed images in order to identify people, and it isn't safe or fair to allow some people to partially cover their heads. But many Minnesota Muslims feel threatened. "I'm shocked," said Fartun Ahmed, a student at Century College in White Bear Lake. "I respect the government and its rules and regulations . . . But I am not willing to take off my headscarf." The safety argument makes no sense to leaders of the United Somali Movement, a group of graduate students and young professionals in the Twin Cities. If anything, photos of bareheaded women could confuse authorities because their images wouldn't look like the same women we see on the streets every day, they said. "There is no need to see the hair or the head because the face is enough to recognize somebody," said Suban Khalif, 23, a Somalia-born student at the University of Minnesota's College of Design.

"You recognize the nose, the eyes, the mouth and that's enough," said Khalif who wears her hijab every day while away from home. Whether or not it was intended, the real effect of the bill would be to curb religious freedom, she said, and to marginalize tens of thousands of minorities in Minnesota. "This legislation will impact the lives of thousands of Muslim women in Minnesota from diverse ethnic and social backgrounds who cover their hair as an expression of faith," she said. A headwear ban potentially would reach beyond Muslims to affect Catholics, Jews and also Sikhs who consider their turbans to be mandatory, said Taneeza Islam, civil rights director for the Minnesota chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR-MN). "We don't want this to turn into a Muslim issue," she said. "We are saying this is an issue that touches all faiths in which believers wear something on their heads." As for the safety concerns, she noted that the State Department allows religious head coverings to be worn in U.S. passport photos and the Transportation Security Administration allows them to stay in place at airport checkpoints. Minnesota Muslims plan to air their arguments against the bill on March 10, when they are scheduled to meet at the State Capitol as part of a national movement called "Muslim Day on the Hill." STARTED WITH POLICE |

| Column |

Minnesota Researchers Take on Deadly Fungus Threatening World's Wheat Crop GREAT RIFT VALLEY, KENYA — A virulent new version of the deadly fungus stem rust is ravaging wheat in Kenya and spreading beyond Africa to threaten one of the world's most important food crops. The urgency of the threat is not lost on crop scientists in American Midwest. In the 1950s, stem rust destroyed half of the wheat crop in North Dakota and Minnesota and slashed yields elsewhere throughout North America's Great Plains. That crisis and others like it prompted scientists to create resistant varieties that have filled breadbaskets worldwide ever since. Now, the killer farmers thought they had defeated 50 years ago is back with a vengeance. It surfaced in East Africa in 1999, jumped the Red Sea to Yemen in 2006 and turned up this year in Iran where it endangers much of Asia. Scientists are powerless to stop its spread and frustrated in their rush to find resistant plants. The disaster unfolding in Kenya could erupt anywhere the rust spores settle. Once established, stem rust can explode to crisis proportions within a year under the right weather conditions, said Norman Borlaug, who deployed techniques he had learned at the University of Minnesota to lead the fight against stem rust in the 20th century. He won a Nobel Peace Prize for saving millions from hunger. "This is a dangerous problem because a good share of the world's area sown to wheat is susceptible to it," Borlaug said. "It has immense destructive potential." Joseph Atrono knows the full measure of its destructive power. His wheat field, on a ridge overlooking the Rift Valley, is a pathetic tangle of broken stems topped by empty hulls where grain should have formed. Along with the crop went the income Atrono needed to feed his wife and four children. |

| Article |

In the Wheat Fields of Kenya, a Budding EpidemicStem Rust, Vanquished by Science Five Decades Ago, Has Returned in a Destructive New Form. GREAT RIFT VALLEY, Kenya -- A virulent new version of a deadly fungus is ravaging wheat in Kenya's most fertile fields and spreading beyond Africa to threaten one of the world's principal food crops, according to the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization. Stem rust, a killer that farmers thought they had defeated 50 years ago, surfaced here in 1999, jumped the Red Sea to Yemen in 2006 and turned up in Iran last year. Crop scientists say they are powerless to stop its spread and increasingly frustrated in their efforts to find resistant plants. Nobel Peace laureate Norman Borlaug, the world's leading authority on the disease, said that once established, stem rust can explode to crisis proportions within a year under certain weather conditions. "This is a dangerous problem because a good share of the world's area sown to wheat is susceptible to it," Borlaug said. "It has immense destructive potential." Coming on the heels of grain scarcity and food riots last year, the budding epidemic exposes the fragility of the food supply in poor countries. It is also a reminder of how vulnerable the ever-growing global population is to the pathogens that inevitably surface somewhere on the planet. The first hint of danger came in an e-mail in 1999 to Ravi Singh, a wheat expert at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Mexico. A scientist who had trained under Singh was reporting findings from field trials in Uganda. Singh said he could not believe what he saw: Plants that were bred to resist stem rust had succumbed to the fungal parasite. "It was shocking," Singh said. "We had never seen such susceptibility. . . . The first thing you think is that it probably is not true." Researchers in South Africa and Minnesota discovered why it was true. In the biological churning that constantly endows old pests with new genetic combinations, stem rust had acquired a frightening ability to punch through the resistance that had guarded wheat for decades. |

| Column |

Obama's Ban on TortureMinnesotans played a role  On June 24, 2007, Douglas Johnson from Minneapolis sat at a dinner in Washington, D.C.'s, historic Tabard Inn, brainstorming strategies for stopping coercive interrogation tactics the White House had authorized in the name of fighting terror. No point in mincing words. They were talking about torture. On Jan. 22 this year, President Obama sat a few blocks from the scene of that dinner and signed an executive order banning the interrogation tactics at issue. Many Americans know the arc of the events leading up to Obama's order. But few know the behind-the-scenes work it took to build support that would help the new president end a practice which had bitterly divided the nation. The idea of an executive order on torture first surfaced in the upstairs dining room of the Tabard Inn where Johnson and some 15 others had gathered amid antique furnishings that called to mind America's traditions. Eventually, the idea was to win support from Republicans and Democrats, former defense secretaries, CIA officers and secretaries of state as well as human rights advocates, legal scholars and clergy members from many denominations and faiths. Looking back at the beginning Johnson — who is the executive director of the Center for Victims of Torture — doesn't take credit for the idea. It started, he said, with Marc Grossman who had been Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs during the first term of former President George W. Bush. Revelations of abuseBush had declared in 2002 that fighters for al-Qaeda and the Taliban were not protected under the Geneva conventions' prohibitions against torturing prisoners of war and treating them in cruel, humiliating and degrading ways. Even so, Bush said, detainees would be treated in a manner consistent with the principles of the Geneva conventions. But evidence to the contrary mounted through revelations of abuses at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq and the U.S. detention facility at Guantanamo Bay. Then, in 2007, Bush acknowledged that the CIA had maintained secret prisons overseas. Reports surfaced that detainees in those lockups had been subjected to waterboarding (a near-drowning experience) and other tactics that shocked many Americans. |

| Column |

My Memorable Obama Moments in Kenya It did not surprise me when I read on AllAfrica.com Friday that Sen. Barack Obama's Kenyan grandmother had cut off interviews because she was exhausted from the media swarm to her remote village in western Kenya. Mama Sarah Onyango Obama, 85, needed a break to watch the election returns, her family explained. I saw enough Obamamania while on assignment in Kenya last month to convince me that a good share the people in the homeland of Obama's father will — like Mama Sarah — be glued to news of far-away U.S. election returns this week. In Nairobi you can find a veritable bazaar of Obama trinkets and sales pitches. One of my favorites was the rush on an East African Breweries beer named Senator. A bartender in Kisumu told the Financial Times, "People now say 'I want an Obama' when asking for Senator." I was in the western city Nakuru, on Oct. 7 when Kenyan authorities scooped author Jerome Corsi from his hotel in Nairobi and gave him the bum's rush to the airport. Authorities said Corsi was detained because he didn't have the right visa. Everyone I talked to assumed the real reason was that Corsi had written the highly critical book "The Obama Nation: Leftist Politics and the Cult of Personality." The legal proprieties didn't matter to the staff at my hotel. They were positively giddy at the news, which was splashed across the front pages of local newspapers. Visit to the countrysideMy most memorable Obama moment came, though, on a day when two Kenyan companions and I drove for hours along a rutted, washboard road through the country's western highlands to talk with farmers from the Maasai tribe. |

| Column |

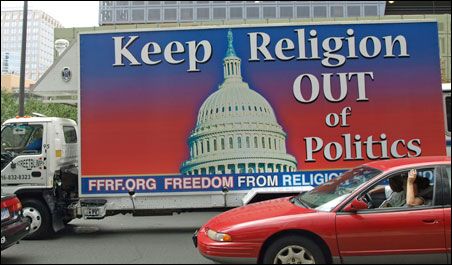

America's Paradox:We want religion in, but out, of politics  "Keep religion out of politics," said a mega sign cruising St. Paul's streets on the back of a truck on Monday, the opening day of the Republican National Convention. But a few blocks away, dozens of anti-war demonstrators marched with placards declaring: "Blessed Are the Peacemakers, For They Will Be Called Sons of God." And Steve Ahlgren's sign said, simply: "1st John 4:7-21." It was a biblical reference to loving God and loving one another, too. And Ahlgren, a lawyer from Lauderdale, insisted that religion expressed like that has a place in politics as a powerful force for good. Religion in politics? Religion out of politics? Two views, same countryBoth positions, paradoxically, express the view of America, one of the most devout nations in the Western world. "Religion plays a crucial role, and it has throughout the history of the Republic," said Dan Hofrenning, a political science professor at St. Olaf College in Northfield. It was a factor in the moral justification of FDR's New Deal, he said, and it was debated intensely when John F. Kennedy, a Roman Catholic, ran for president. Religion provided moral authority for the civil-rights movement in the 20th century, and it played a role in women's drive for suffrage. Indeed, religion trumps the issues for many Americans. And voters who perceive a candidate as sharing their own faith and a related set of values will forgive the candidate on a range of issues. |

| Article |

The Next Big Stem Cell Fight: Mixing Cow and Human DNA In Gary Larson’s wacky Far Side world, cows and humans swap traits with hilarious results. Nobody is laughing, though, over a real-world bid to mix cow and human DNA, something scientists here say they must do in order to advance stem cell studies. Debate over this step in the exploration of stem cells already has reverberated across the Atlantic. Sen. Norm Coleman, R-Minn., is a co-sponsor of a bill that would ban the research in the United States. From the first test-tube baby to the first cloned animal, scientists in this part of the world have led a biological revolution that set off an uproar in the United States but met relative calm here. Now, though, the research is crossing a line that has shattered the calm and ignited fiery debate all the way up to Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s cabinet. The line at issue is the notion that the human animal is fundamentally different from all other creatures on Earth—in a sacred sense for many people of many faiths. "From a Christian viewpoint, the teaching is, of course, that we are made in the image of God, and there is something special about human life in relation to divinity," said Sir Brian Heap, a prominent Cambridge University biologist who has helped his government |

| Column |

What Presidential Candidates--and the Rest of Us--Can Learn from Chimps The pundits were wrong, de Waal wrote in the March 1 issue of New Scientist. To claim the considerable power of an alpha female, Clinton needed to present herself as older, as the leader of a large block of other women and as an effective bridge builder. In short, she needed to come off as more of an Indira Gandhi than a Paris Hilton in her campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination. It was a classic example of de Waal's work over the years to further understanding of human culture and behavior by drawing lessons from apes. His acclaimed books — "Our Inner Ape, The Ape and the Sushi Master" and others — have mesmerized readers with profound insights into power, sex, kindness and violence. Engaging non-scientists Long recognized as a pre-eminent scientist, de Waal was named in 2007 to Time magazine's list of the 100 men and women whose power, talent, or moral example is transforming the world. But he's given every reason to expect he will deftly engage non-scientists in his lectures. On Comedy Central in January, de Waal mixed clear science with a straight-but-droll delivery. "The only reason we biologists don't call humans apes is to protect the fragile human ego," de Waal told Stephen Colbert on "The Colbert Report." Years ago, protestors confronted de Waal over his human-ape comparisons, but that has subsided, he said in a telephone interview on Wednesday. "There may be creationists out there who hate what I say," he said. "But I never run into them. I think it's because they won't come to my kind of lectures." |

| Column |

Our World Changed 50 Years Ago Today Echoes of the Cold War are sounding today as American scientists celebrate the 50th anniversary of the launch of Explorer 1, the nation's first successful satellite. With a sky full of space hardware in 2008, it may be difficult for a new generation to imagine the immense relief Americans expressed as the bullet-shaped craft settled into orbit. The Russians had shattered confidence in U.S. leadership with their launch of the Sputnik 1, the world's first artificial satellite on Oct. 4, 1957. A month later came Sputnik 2, carrying a dog named Laika. The starting gun had sounded on the space race, and the United States stumbled in its first strides. In December 1957, the United States' Vanguard satellite rose about four feet, then lost engine thrust, fell back upon the launch pad and exploded into flames. William Garrard remembers being "scared to death" as a high school student in Austin, Texas. "Everybody was so rightly frightened," Garrard said. "All over the world people said it looks like the United States is history. Russia is leading in technology." Now Garrard heads the Minnesota Space Grant Consortium and also works as a professor of aeronautical engineering at the University of Minnesota. With a half century of hindsight, Garrard said Wednesday that the United States wasn't truly trailing the Soviet Union in science and technology. |

| Column |

Global Warming's Pressing Moral Question A pressing moral question for these times came from the audience last week at a "Headliners" event, where experts meet monthly with the community on the University of Minnesota's St. Paul Campus. Professor Deborah Swackhamer, featured expert for January, had been talking about some disturbing changes Minnesota could expect if greenhouse gas emissions aren't curbed and global warming continues apace. Swackhamer is interim director of the University's new Institute on the Environment. As is true in most discussions of climate change, the talk called for crossing a certain time warp: We can't yet see the full effect of the impending change. We also can't see real benefits from steps we take to mitigate the problem. Both the dangers and the rewards belong to a future generation. "We can't afford to wait," Swackhamer said. "We must make these changes now for our children to see an impact." Then came the question from the back of the room. "Is there any historical precedent for people making a large societal change when they don't, in fact, feel a crisis — when they don't see the bullet coming?" a man asked. "Is there any historical precedent for one generation deciding to be generous to its own children?" |

| Column |

FDA Approves Cloned Food....... and braces for backlash  As expected, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has ruled that "meat and milk from clones of cattle, swine, and goats ... are as safe to eat as food from conventionally bred animals." And, as expected, controversy continues to rage over the very notion that products from clones could take a place at the nation's meat counters and dairy cases. On the heels of the FDA's announcement today, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) called for continuing a voluntary moratorium on sales of food from clones. Companies doing cloning had agreed to withhold the meat and milk while the FDA deliberated on the safety question. The USDA official making the call — Bruce Knight, under secretary for marketing and regulatory programs — didn't say how long the moratorium should continue. A Q&A; issued with Knight's statement said that the USDA needs "a sufficient period of time to prepare so that a smooth and seamless transition into the marketplace can occur." Special labels?One smoldering argument is the question of whether food from clones should be specially labeled. Anticipating that fight, the FDA said in its announcement that it will not require any labeling. The USDA echoed that decision. Instead, the FDA said producers of the foods may be able to label their products as "clone-free." Such labels might be allowed on a case-by-case basis, the FDA said, to ensure that the labels are truthful and not misleading. The approach would be similar to a compromise government regulators reached years ago during the uproar over milk from cows given a genetically engineered hormone, popularly known as BST, to boost milk output. Dairies that could certify their milk came from herds not treated with BST were able to say so and charge a premium for the milk. But consumer groups and many bloggers were quick today to denounce any similar compromise over food from clones. The Center for Food Safety in Washington, D.C., said the FDA's position "deprives consumers of their right to know about the origins of their food." A headline in Wired's blog network chided the FDA's "Don't Ask, Don't Tell on Cloned Meat." |

| Column |

Here's Hoping........ for Charles Darwin's spirit  Of course, Charles Darwin can't come back to life. But somehow I wish his open-minded spirit and dogged intellectual honesty could visit our 2008 political arena where the question of how we humans got our origins will, once again, divide America. Full disclosure: The editors asked me to write about my greatest wish for next year. This isn't my greatest wish, given wars raging around the world and many other reasons to worry about my children's future. But I've wanted to write this piece ever since I had a chance last summer to view Darwin's papers at the University of Cambridge in England. Schooled by clerics, Darwin wrestled with faith in an omniscient creator even while he stretched his mental horizons to ponder evidence that mysteries of Earth's intricate life could be explained by a scientific theory.

"I am in an utterly hopeless muddle," Darwin wrote to his friend Asa Gray in November, 1860. "I cannot think that the world, as we see it is the result of chance; & yet I cannot look at each separate thing as the result of Design." That muddle is central to my wish. It isn't easy to open the mind and think creatively about America 2008, its urgent needs and its role in the world. Such thinking requires the humility to drop partisan defenses and listen to the other side. It demands attention to the details of national policy at a time when the overwhelming preferences are entertainment and shopping. Darwin did it and came up with a theory that gives a common thread to all life on earth — the lives of Christians and Muslims, Hutus and Tutsis, lowly microbes and astrophysicists. |

| Column |

Research and Ethical Questions Remain Following Stem-Cell Breakthrough |

| Column |