Amy Sullivan

Amy Sullivan is a senior editor at Time magazine, where she writes about politics, religion, and culture. Previously, she worked as editor at the Washington Monthly and as editorial director at the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. Her first book, The Party Faithful: How and Why Democrats are Closing the God Gap, was published in 2008. Her work has appeared in publications including the Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times, New Republic, and Washington Post, and was anthologized in The Best Political Writing 2006. She is a frequent guest on radio and television talk shows.

| Column |

Is the Death Penalty in Keeping with Catholic Doctrine? September has been execution season in the United States. In the past month, Texas executed two prisoners, Florida and Alabama each sent an inmate to the death chamber, and in Georgia, the controversial lethal injection of Troy Davis went forward despite last-minute consideration of his case by the U.S. Supreme Court. The justices did halt the scheduled executions of two other Texas inmates, and Republican Governor John Kasich commuted the death sentence of an Ohio prisoner. The issue has even reentered the realm of presidential politics, after all but disappearing for several decades. In his first debate with fellow GOP contenders, Texas Rick Perry fielded a question about the record number of executions over which he has presided as governor (234 at the time of the debate, 236 now). "Have you struggled to sleep at night with the idea that any one of those might have been innocent?" asked moderator Brian Williams. "I’ve never struggled with that at all," was Perry’s response, delivered to an approving audience of conservatives who applauded the number of Texas executions. But if Perry hasn’t struggled with the application of the death penalty, what about the Catholic justices who hold the power to stop a man’s execution or allow the state to kill him? Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia addressed that question earlier this week in a speech at a Catholic law school in Pittsburgh. "If I thought that Catholic doctrine held the death penalty to be immoral," said Scalia, "I would resign. I could not be a part of a system that imposes it." |

| Column |

The Importance of Understanding Religion in a Post-9/11 World It’s hard to remember now, but in the days immediately following the attacks of 9/11, a spirit of religious unity reigned. Shocked political foes gathered together at the Washington National Cathedral for a prayer service that included a Muslim imam who read verses from the Koran. Just a few days later, George W. Bush quoted from the Koran himself at the Islamic Center in Washington, and told the country that "Islam is peace." It didn’t take long, however, for the tender feelings of togetherness and tolerance to be replaced by division and hostility. Some thought leaders and policymakers embraced Samuel Huntington’s idea that the West was engaged in a "clash of civilizations" with Islam. Meanwhile, neo-atheists led by Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens put forward their own theory of a world split between civilized secularists and dangerous religionists. Secular academics and other thinkers have predicted and hoped for decades that as societies become more advanced, religion and its institutions would become less relevant. To them, 9/11 was further proof that religion is incompatible with modernity. But while the last 10 years have inspired many difficult discussions about the relationship between religious communities and democratic societies, they have also proven that the decline of religion is not inevitable in modern society. Trust in religious institutions and leaders has fallen, as it has for secular institutions as well. But Americans continue to value religion–85% consistently tell Pew pollsters that religion is an important part of their lives. And the relocation of religious immigrants to the U.S. and parts of Europe has insured that the West is by no means a civilization in which religion is invisible. We read most often about the conflicts that occur in our modern communities over religion: the banning of hijab in France, fights over plans for an Islamic center in lower Manhattan, debates over the teaching of evolution in public schools. But in our focus on these conflicts, we too often miss something fascinating that is going on. Ancient religious traditions are not fading away in the face of modernity. They are adapting–and forcing modern societies to adapt to them as well. High school football players in Dearborn, Michigan, schedule midnight practices during Ramadan. Conservative Christians study political theory and snag competitive internships in Washington. Christian Scientists lobby Congress and win provisions to cover their practitioners in health reform. And the wishful thinking of the neo-atheists ignores the fact that a little religion often does a lot of good. The British psychiatrist Russell Razzaque, a Muslim, has studied jihadists and discovered that many came from families that were not terribly religious. Their lack of familiarity with the Koran and Muslim teachings left them vulnerable to the distorted version of Islam that radicalists preached. By contrast, those potential recruits like Razzaque who grew up in religious homes knew enough about the Koran to recognize that something was off about the jihadist message. |

| Column |

What Journalists Should Be Asking Politicians About Religion A few weeks ago, I opened up my Twitter feed early in the morning and immediately wondered if I was being punk’d. Instead of the usual horse race speculation, my colleagues in the political press corps were discussing the writings of evangelical theologian Francis Schaeffer and debating the definition of Dominionism. The same week, a conservative journalist had posed a question about submission theology in a GOP debate, and David Gregory had grilled Michele Bachmann about whether God would guide her decision-making if she became President. The combination of religion and politics is a combustible one. And while I’m thrilled to see journalists taking on these topics, it seemed to me a few guidelines might be helpful in covering religion on the campaign trail: Ask relevant questions.The New York Times‘ Bill Keller published a column last weekend calling for journalists to ask candidates "tougher questions about faith" and posing a few of his own. The essay was flawed on its own terms. It read like a parody of an out-of-touch, secular, Manhattan journalist–comparing religious believers to people who believe in space aliens, and referring to evangelical Christian churches as "mysterious" and "suspect." But it also identified the wrong problem. It’s not necessarily tougher questions that are needed but more relevant questions than journalists normally pose. It’s tempting to get into whether a Catholic candidate takes communion or if an evangelical politician actually thinks she speaks to God. But if a candidate brings up his faith on the campaign trail, there are two main questions journalists need to ask: 1) Would your religious beliefs have any bearing on the actions you would take in office? and 2) If so, how? |

| Broadcast |

Values AddedSouthern Baptist Edition Amy Sullivan and Richard Land talk about Southern Baptists Is the religious right dead? And is that a stupid question? (06:13) Richard: Perry is Bush on steroids (02:24) Why Southern Baptists hate Obamacare (02:40) The Christian case for comprehensive immigration reform (08:31) What do voters deserve to know about a politician’s faith? (07:20) Questions for Obama about his Christian faith (03:23) |

| Column |

The Sharia Myth Sweeps America If you are not vitally concerned about the possibility of radical Muslims infiltrating the U.S. government and establishing a Taliban-style theocracy, then you are not a candidate for the GOP presidential nomination. In addition to talking about tax policy and Afghanistan, Republican candidates have also felt the need to speak out against the menace of "sharia." Former Pennsylvania senator Rick Santorum refers to sharia as "an existential threat" to the United States. Pizza magnate Herman Cain declared in March that he would not appoint a Muslim to a Cabinet position or judgeship because "there is this attempt to gradually ease sharia law and the Muslim faith into our government. It does not belong in our government." The generally measured campaign of former Minnesota governor Tim Pawlenty leapt into panic mode over reports that during his governorship, a Minnesota agency had created a sharia-compliant mortgage program to help Muslim homebuyers. "As soon as Gov. Pawlenty became aware of the issue," spokesman Alex Conant assured reporters, "he personally ordered it shut down." Former House speaker Newt Gingrich has been perhaps the most focused on the sharia threat. "We should have a federal law that says under no circumstances in any jurisdiction in the United States will sharia be used," Gingrich announced at last fall's Values Voters Summit. He also called for the removal of Supreme Court justices (a lifetime appointment) if they disagreed. Gingrich's call for a federal law banning sharia has gone unheeded so far. But at the local level, nearly two dozen states have introduced or passed laws in the past two years to ban the use of sharia in court cases. Despite all of the activity to monitor and restrict sharia, however, there remains a great deal of confusion about what it actually is. It's worth taking a look at some facts to understand why an Islamic code has become such a watchword in the 2012 presidential campaign. What is sharia?More than a specific set of laws, sharia is a process through which Muslim scholars and jurists determine God's will and moral guidance as they apply to every aspect of a Muslim's life. They study the Quran, as well as the conduct and sayings of the Prophet Mohammed, and sometimes try to arrive at consensus about Islamic law. But different jurists can arrive at very different interpretations of sharia, and it has changed over the centuries. Importantly, unlike the U.S. Constitution or the Ten Commandments, there is no one document that outlines universally agreed upon sharia. |

| Broadcast |

Values AddedIt's the Religion, Stupid Amy Sullivan and Melinda Henneberger chat about religion. Values Added: It’s the Religion, Stupid Just how Mormon is Jon Huntsman? (08:21) "Big Love" and the mainstreaming of Mormonism (05:31) The real meaning of "Obama is a Muslim" (09:53) Family values face-off: Bachmann vs. Palin (03:11) The anti-Boehner protest at Catholic University (11:43) Setting the record straight on Paul Ryan and Archbishop Dolan (08:01) |

| Broadcast |

Values Added: It's the Religion, Stupid

Values Added: It’s the Religion, Stupid Just how Mormon is Jon Huntsman? (08:21) "Big Love" and the mainstreaming of Mormonism (05:31) The real meaning of "Obama is a Muslim" (09:53) Family values face-off: Bachmann vs. Palin (03:11) The anti-Boehner protest at Catholic University (11:43) Setting the record straight on Paul Ryan and Archbishop Dolan (08:01) |

| Broadcast |

Values Added: The Praying FieldAmy: Democrats foolishly conceded the faith vote (05:02) When pastors say you can’t be a Democrat and a good Christian (06:11) Does Tom Perriello’s narrow loss point the way forward? (07:18) Oklahomans vote against the looming scourge of Shariah law (05:50) The growing idea that Islam isn’t a real religion (03:24) Glenn Beck, Pamela Geller, and innovations in hatred (11:47) |

| Column |

Barack Obama is Not a Muslim But not only has that fact not gotten through to many Americans, the percentage of adults who believe he is a Muslim has now risen sharply after holding steady for two years, according to a new Pew poll out today. For my money, though, the real headline--and the news that should be causing heartburn over at the White House right now--is that the percentage of Americans who can correctly identify Obama's religious faith as Christian has dropped by 14 points in the past year and a half. A plurality of Americans (43%) have no idea what religion he practices. I'm going to repeat that because this is very unusual: a year and half after Obama moved into the White House, Americans are far less certain about who he is than they were during the campaign. That isn't a good trend line for any political figure, but especially not the president. It may be appealing for an offbeat Hollywood actor or a reclusive writer to be seen as an enigma. But politics is a personal arena--voters like to feel that they can relate to a president or at the very least understand who he is. More dangerous for Obama is the fact that if a politician doesn't define himself, his enemies are more than happy to do it for him. The Pew poll is evidence that the endless conservative media cycle of misinformation about Obama is working: of those respondents who identified Obama's faith as Islam, 60% said they learned the "fact" from the media. (Note that the poll was conducted before Obama waded into the so-called Ground Zero mosque controversy.) Barely one-third (34%) of Americans can correctly identify Obama as a Christian, compared to more than half (51%) who could do so during the 2008 campaign. But that huge drop isn't driven primarily by Fox News true believers. (Let me pause for a moment here to say that it is of course not a smear to call someone a Muslim. It is, however, obnoxious to say someone is a member of a religious faith when he's not--and to insist that he is not a member of the tradition he does claim. It would also be foolish and naive to pretend that conservatives who call Obama a Muslim are doing it in a neutral way and that their intention is not to raise questions about his "otherness.") Consider this: Less than half of Democrats (41%) know Obama is a Christian, down from 55% in March 2009. Barely four-in-ten African-Americans say he's a Christian, down from 56% last year. The percentage of moderate and liberal Republicans who say Obama is a Christian has dropped by 27 points, but it's not because they're all now convinced he's a Muslim. Instead, the percentage who just don't know his religion has risen 19 points. "What the numbers say," says Alan Cooperman of the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, "is that there's a lot of uncertainty and confusion about the president's religion." |

| Discussion |

Values Added: Religious PersuasionsHow the press botched the story of the murdered missionaries (11:45) Debating the strategies of gay marriage advocates (18:23) Is the "Ground Zero mosque" full of holy fools? (05:24) Politicians fanning anti-Islam flames (07:31) What’s behind Uganda’s anti-homosexuality bill (06:04) Anne Rice quits Christianity, enrages Amy (05:17) |

| Column |

Young EvangelicalsExpanding their mission  With few job openings available for graduating seniors, recruiters are an especially welcome sight on college campuses these days. When Josh Dickson, a recruiter at Teach for America, would show up at liberal-arts colleges this year, the earnest 25-year-old would hear student after student explain that their most urgent desire had always been to teach in a low-income community. It may sound like exactly the kind of interaction that takes place on hundreds of campuses across the country. But there's something distinctive about the colleges and universities where Dickson has been doing his recruiting: they're all religious schools. And Dickson isn't your standard nonprofit recruiter. A devout Christian, he honed his persuasion techniques evangelizing to classmates as a leader of his university's chapter of Campus Crusade for Christ. With the touch he refined telling football players they should care more about their eternal souls than the next keg party, Dickson has been seeking out student all-stars at places like Illinois's Wheaton College, long known as the Harvard of Evangelical schools. During interviews, he heard a lot of students say variations of what one Wheaton senior told him: "I just think God has given me a heart for social justice." For many people, the word Evangelical evokes an image of fire-and-brimstone conservatism. Pat Robertson's suggestion this past winter that Haiti had brought its earthquake on itself through a Satanic pact may have been an extreme example, but it's the kind of pronouncement we've come to expect from a certain generation of Evangelical leaders. Today's young Evangelicals cut an altogether different figure. They are socially conscious, cause-focused and controversy-averse. And they are quickly becoming a growth market for secular service organizations like Teach for America. Overall applications to Teach for America have doubled since 2007 as job prospects have dimmed for college graduates. But applications have tripled from graduates of Christian colleges and universities. Wheaton is now ranked sixth among all small schools — above traditionally granola institutions like Carleton College and Oberlin — in the number of graduates it sends to Teach for America. The typical Wheaton student, like many in the newest generation of Evangelicals, is likely to be on fire about spreading the Good News and doing good. |

| Column |

Religious Groups Push for Immigration Reform When Los Angeles Cardinal Roger Mahony heard about Arizona's new immigration-enforcement law, the Catholic leader reacted with some good old-fashioned righteous anger. Taking to his blog, Mahony blasted the measure as the country's most retrogressive, mean-spirited and useless anti-immigration law, comparing it to German Nazi and Russian communist techniques that forced individuals to turn one another in. Mahony is hardly the only religious leader outraged by Arizona's approach to immigration, which requires police to ask for papers from anyone they suspect is in the country illegally. The progressive Evangelical leader Jim Wallis has declared the state's new law a social and racial sin. The president of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society declared that by passing the law, Arizona has taken itself out of the mainstream of American life. And Mahony's Catholic colleague the bishop of Tucson has suggested that the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) join lawsuits challenging the law. (See the top 10 religion stories of 2009.) The vigorous response to the Arizona law from faith communities is providing new energy to a national campaign for immigration reform that was already gathering steam this spring, including a massive rally in March on the National Mall. In the past week, however, Democratic leaders have sent mixed signals about their willingness to press ahead with immigration reform this year. Senate majority leader Harry Reid is backing off his vow from last week to make the issue a priority with or without GOP support. Similarly, after appearing to endorse swift action last weekend, President Barack Obama told reporters that there may not be an appetite to reform immigration laws this year. If immigration reform does fight its way to the top of the Democratic agenda, it will be largely through the efforts of a remarkably broad coalition of religious leaders. The near universal support among religious groups for comprehensive immigration reform, including a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, is a change from the bruising fights over health reform that often saw faith leaders facing off against one another. But across theological lines, religious advocates say their traditions obligate them to care for immigrants. As the group New Evangelicals for the Common Good put it in a statement opposing the Arizona law, throughout the Bible, God commands us in no uncertain terms to show kindness and hospitality to the foreigner and the stranger. (See pictures of spiritual healing around the world.) |

| Discussion |

Values Added: National Day of DiavlogThis discussion between Amy Sullivan (Time Magazine) and David Gibson (Politics Daily) covers: Is Obama co-opting, neutralizing the National Day of Prayer? (13:46) Ramifications of the "Mojave cross" case ruling (03:35) Does a Supreme Court justice’s religion still matter? (10:53) The Court and the rise of the Religious Right (01:08) What did Pope Benedict know, and when did he know it? (12:05) Churches attack AZ immigration law, call for national reform (09:39) |

| Article |

Could Abortion Sink Health Care Reform? Leading up to Thursday's health care summit, there has been plenty of chatter about everything from consideration of an excise tax on so-called Cadillac insurance plans to whether President Obama will sit at the table with congressional leaders or speak from a podium. But Democrats and Republicans alike have uttered hardly a word about an issue that could sink the health reform effort unless it is resolved: abortion. The silence is surprising given that disagreements about abortion coverage almost scuttled health reform in the House last fall. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi wasn't able to gather sufficient votes to pass the health reform bill until after she struck a deal with pro-life Democrat Bart Stupak to allow a vote on his amendment that would prohibit plans that cover abortion in an insurance exchange from receiving federal subsidies. The House voted to approve the amendment's tough language, which became part of the final bill. Even so, heading into the health summit, no one — from the White House on down — knows whether abortion will still be an obstacle to passing a reform bill. (See the top 10 players in health care reform.) The proposal Obama released on Monday does not address the question of abortion coverage. Both pro-life and pro-choice politicians are interpreting that absence to mean that the White House supports using the abortion provision authored by Nebraska Senator Ben Nelson, which became part of the Senate version of health reform. The Nelson language, less restrictive than Stupak's, would allow a woman receiving federal subsidies to purchase insurance from a plan that covers abortions, but those subsidies must be segregated and not used to pay for abortion procedures. The U.S. Conference on Catholic Bishops has made clear that it considers the Nelson language "deficient," and Stupak released a statement on Tuesday declaring that anything short of his abortion restriction would be "unacceptable." Shortly after the House bill passed in November, Stupak vowed that 40 Democrats would stand with him to vote against final passage of health reform if his strict language was not included. (See TIME's health and medicine covers.) |

| Column |

Rwanda's "Miracle" of ForgivenessA man with a machete attacks and kills your family. Repeat this scene on a genocidal scale. Would you forgive? Could you? Rwandans are, as human instinct and faith intersect in this African nation.  Kigali, Rwanda— Rosaria Bankundiye and Saveri Nemeye are neighbors in the tiny village of Mbyo, south of Kigali. On a steamy morning, they sit in the cool living area of the clay house Saveri helped build for Rosaria just a few years ago. Two of his sons roll around on the floor while the adults talk. At one point, Saveri leans over to say something to Rosaria and she starts laughing, her smile wide. They have known each other for a long time.Nearly 16 years ago, during the genocide that wracked this African country of 10 million people for 100 days in 1994, Saveri murdered Rosaria's sister, along with her nieces and nephews. Genocidaires also attacked Rosaria, her husband and their four children with machetes and left them for dead. Only Rosaria survived. Yet when Saveri came to beg her forgiveness after he was released from prison in 2004, Rosaria considered his request and then granted it. "How can I refuse to forgive when I'm a forgiven sinner, too?" she asks. Nearly every religion preaches the value of forgiveness. To most of us, however, such an act of mercy after so much pain seems unthinkable — maybe even unnatural. Scientists have long suspected that we are born with an instinct to seek revenge against those who hurt us. When someone like Rosaria overrides that vengeance instinct with an act of radical forgiveness, it can only be a miracle from God. Now a growing number of researchers in the fields of evolutionary biology and psychology also believe that humans have a built-in inclination to forgive. In Rwanda, where government and church leaders are actively encouraging citizens to forgive each other, Rosaria's remarkable reconciliation with the man who killed her loved ones was not inevitable. But it is surprisingly understandable. It is intuitively easy to grasp the instinct to enact vengeance. Michael McCullough, a psychology professor at the University of Miami, writes in his book Beyond Revenge that revenge serves several key functions for humans and other species: It deters potential aggressors and discourages those who have harmed you from repeating the offense. But McCullough also argues that reconciliation and forgiveness are equally essential to the development and maintenance of a thriving community. If kinsmen punish a bully by casting him out of the group or by killing him, they lose both his ability to contribute to the community and their own genetic material — an evolutionary no-no. Over time, individuals and species with more conciliatory tendencies are more successful because they promote their own kin. |

| Interview |

Therese Borchard on Overcoming Depression Therese Borchard writes about depression every day on her award-winning blog at Beliefnet.com. But it took a special leap of faith to share the stories of her breakdowns, hospitalizations and ongoing struggle with depression in her new book Beyond Blue: Surviving Depression & Anxiety and Making the Most of Bad Genes. "This will do wonders for my chances of future employment," she cracks. TIME writer Amy Sullivan talked with Borchard about the challenges of writing about mental illness (especially one's own) at the writer's home in Annapolis, Md. The story you tell is very raw and can't have been easy to share. What made you decide to write this book? I didn't write it for about 18 years because I thought that writing about your own life was self-indulgent. But then I thought about what kept me going through the darkest days, reading memoirs by other people who have struggled with depression — Kay Redfield Jamison, Anne Lamott — and who emerged even stronger and more capable. When you're in the midst of depression, that's the scariest thing — it seems that you're going to feel like that forever. The pain created by depression kills almost 1 million people a year. It almost killed me, and it did kill my aunt. If I can give just one person hope that there's an end to depression, that it is treatable, then that made it worth it for me to write the book. Have you reached the point where you feel that your depression is treatable? I have. At first I was overmedicated by a psychiatrist — going through so many combinations of medications — and that made me very afraid of trusting psychiatrists and drugs. So I went from that extreme to doing everything holistically and hoping yoga, acupuncture and meditation would cure me. What I've found now is a happy medium between the two. I wanted to ask you about your experience with psychiatrists because you really ran the gauntlet through multiple doctors before you found the right fit. My psychiatrist told me it's usually 10 years before you find the right doctor and right medication, especially when you're bipolar like I am. That was true with me. I was exhibiting symptoms in college — and seeing a few psychiatrists — but it wasn't until 10 years |

| Interview |

Mary Karr on Becoming Catholic Mary Karr has written two bruising memoirs—including the 1995 best-seller The Liars' Club—about her rough childhood and alcoholic parents. In Lit, her latest volume, Karr takes on the painful task of recording her own descent into addiction and depression. A lifelong agnostic, she achieved sobriety through the guidance of friends and by turning to spirituality. Karr is now a church–going, Bible–reading, Ignatian–prayer-saying Catholic, and she talked to TIME about her unlikely journey. Did you grow up in a religious home?My mother tried on religions the way she did husbands—she was married seven times. She did yoga back in 1962 before it was popular, she took us to the Christian Science church a few times, she read a lot about Buddhism. My father thought church was a trick on poor people. And I was a full–bore agnostic. For a long time, I didn't know people were serious about God. So how did you form your ideas about religion? As you write about yourself in your twenties and thirties, you definitely didn't think God was anything a rational person would believe in.I had a very Kafkaesque worldview. It was partly because of all the bleak things that happened to me and partly because of my philosophy background. I took a lot of philosophy in college. Christianity all seemed very comical to me. I remember meeting Robert Bly at a poetry workshop—he was a preacher's son—and he was talking to me about my soul. I said, "I don't have a soul. What are you talking about?" In the book, one of the reasons you reluctantly give prayer and spirituality a try is because you see a difference between recovering alcoholics who are religious and those who aren't.That is my experience. I know a lot of people who have been able to quit drinking and a lot of them can be pretty angry. What kept me |

| Column |

The Obamas Find a Church Home — Away from Home For the past five months, White House aides and friends of the Obamas have been quietly visiting local churches and vetting the sermons of prospective first ministers in a search for a new — and uncontroversial — church home. Obama has even sampled a few himself, attending services at 19th Street Baptist on the weekend before his inauguration and celebrating Easter at St. John's Episcopal Church. Now, in an unexpected move, Obama has told White House aides that instead of joining a congregation in Washington, D.C., he will follow in George W. Bush's footsteps and make his primary place of worship Evergreen Chapel, the nondenominational church at Camp David. A number of factors drove the decision — financial, political, personal — but chief among them was the desire to worship without being on display. Obama was reportedly taken aback by the circus stirred up by his visit to 19th Street Baptist in January. Lines started forming three hours before the morning service, and many longtime members were literally left out in the cold as the church filled with outsiders eager to see the new President. Even at St. John's, which is so accustomed to presidential visitors that it is known as the "Church of the Presidents," worshippers couldn't help themselves from snapping photos of Obama on their camera phones as they walked down the aisle past him to take communion. The challenge of not only being part of a church community but also praying in peace has long been a problem for Presidents, according to historian Carl Sferrazza Anthony. "McKinley hated having people staring at him while he read Psalms, sang hymns, put money in the collection plate or took communion," he writes in America's First Families. "By the 1920s, getting a presidential family in and out of church was a production. Secret Service agents had to cordon off a clear path from the curb to the church entrance before the Coolidges arrived ... [and] they were swiftly escorted to their third-row pew." The Clintons attended Foundry United Methodist Church on 16th Street, and were particularly active during the years before Chelsea left for college. But White House aides say that security measures required by the Secret Service have become stricter since 9/11 and would cause significant delays for parishioners — and at significant cost to taxpayers — on Sunday mornings. Given Obama's popularity within the African-American community, the President also worried that if he chose a local black congregation, church members would find themselves competing with sightseers for space in the pews. |

| Interview |

Can Science Find God?An interview with Barbara Bradley Hagerty  For NPR correspondent Barbara Bradley Hagerty, religion is more than just a beat. Hagerty was raised as a Christian Scientist and grew up listening to her grandmother's stories of healing illnesses and serious injuries through prayer. As an adult, Hagerty became a Protestant Christian after experiencing her own encounter with a divine presence, a moment she describes as "spooky." In her new book, Fingerprints of God: The Search for the Science of Spirituality, Hagerty goes on a professional and personal journey to discover whether science can explain religious phenomena like healing or mystical experiences — and ultimately whether it can prove the existence of God. You were raised Christian Scientist, but this week you're on a bunch of medications for various throat and ear infections. What happened?It kind of started with Tylenol. I had never taken a pill, never gone to the doctor, but one winter when I was 32 years old, I came down with the flu. I was miserable, shaking, drifting in and out of consciousness. In a lucid moment, I remembered someone had left Tylenol in my medicine cabinet. I pulled the bottle out, took one, and crawled back into bed. (See pictures of spiritual healing around the world.) I had been taught that drugs have no power over your body, that it's all your thinking. But within five minutes the shivering just stopped. It took me about a year to leave Christian Science, but that was the end of my formal faith in it. It turned out not to be the end, however, of how I thought about how thoughts affect the body. (Read TIME's cover story on how faith can heal.)You had a spiritual experience that led to this book as well.Yes. In the summer of 1995, I was interviewing a woman who was a member of Saddleback Church in California. It was dark and we were sitting outside in a circle of light under a lamppost while she talked to me about her faith. The moment itself is hard to describe. It's as if someone stood on the edge of the circle and was breathing on us. A warm, moist air surrounded us. She was mid-sentence and stopped talking. It was a moment like I hadn't felt before — or since. There was the presence of something else that was spiritual around us. It lasted 30 seconds, maybe a minute, and then it just kind of receded like a wave and was gone. This book really came from that moment, feeling that presence. It was an attempt to find out whether I was crazy or not.That's pretty unusual stuff from an NPR correspondent. Were you hesitant at all to write about this? |

| Column |

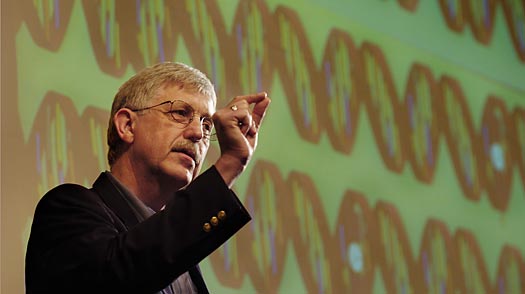

Helping Christians Reconcile God with Science For many young Christians, the moment they first notice discrepancies in the Biblical tales they've faithfully studied is a rite of passage: e.g., if Adam and Eve were the first humans, and they had two sons — where did Cain's wife come from? The revelation that everything in the Bible may not have happened exactly as written can be startling. And when the discovery comes along with scientific evidence of evolution and the actual age of planet Earth, it can prompt a full-blown spiritual crisis. That's where Francis Collins would like to step in. A renowned geneticist and former director of the Human Genome Project, Collins is also an evangelical Christian who was the keynote speaker at the 2007 National Prayer Breakfast, and he has spent years establishing the compatibility between science and religious belief. And this week he unveiled a new initiative to guide Christians through scientific questions while holding firm to their faith. After his best-selling The Language of God came out three years ago, Collins began receiving thousands of e-mails — primarily from other Evangelicals — asking questions about how to reconcile scriptural teachings with scientific evidence. "Many of these Christians have been taught that evolution is wrong," Collins explains. "They go to college and get exposed to data, and then they're thrust into personal crises of great intensity. If the church was wrong about the origins of life, was it wrong about everything? Some of them walk away from science or faith — or both." Collins, 59, who with his mustache and shock of gray hair looks like former U.N. Ambassador John Bolton's cheerful twin, seems genuinely pained by the idea that science could be viewed as a threat to religion, or religion to science. And so he decided to gather a group of theologians and scientists to create the BioLogos Foundation in order to foster dialogue between the two sides. The name — combining bios (Greek for "life") and logos ("the word") — is also what Collins calls his blended theory of evolution and creation, an approach he hopes can replace intelligent design, which he derides as "not a scientific proposal" and "not good theology either." |