Marc Kaufman

Marc Kaufman writes about NASA and space issues for the Washington Post, where he has been a reporter on the national staff for ten years. He has also worked as a foreign correspondent at the Post, reporting from Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks, and as New Delhi bureau chief for the Philadelphia Inquirer. His articles have appeared in the Washington Post, Philadelphia Inquirer Sunday, and New York magazines, as well as Smithsonian and Condé Nast Traveler.

| Broadcast |

The High Probability Of Finding 'Life Beyond Earth' Scientific interest in extraterrestrial life has grown in the past 20 years. The field of astrobiology now includes researchers from a wide variety of disciplines — microbiologists studying bacteria that survive in the most extreme conditions on Earth; astronomers who believe there may be billions of planets with conditions hospitable to life; chemists investigating how amino acids and living organisms first appeared on Earth; and scientists studying rocks from Mars are seeing convincing evidence that microbial life existed on the Red Planet. In First Contact: Scientific Breakthroughs in the Hunt for Life Beyond Earth, Marc Kaufman, a science writer and national editor at The Washington Post, explains how microbes found in some of Earth's most inhospitable environments may hold the key to unlocking mysteries throughout the solar system. Kaufman talks with Fresh Air's Dave Davies about the ongoing search for life in the universe — from current research, to the unknowns in the field. "There are undoubtedly billions or trillions of planets out there and there are most likely billions in the Milky Way itself — just one of billions of galaxies," Kaufman says. "There are billions of planets in habitable zones in relation to their stars that would allow for water to be liquid and for other important conditions for life." |

| Review |

Review: First ContactScientific Breakthroughs in the Hunt for Life Beyond Earth by Marc Kaufman  It wasn’t that long ago that the field of astrobiology—the search for life beyond Earth—operated towards the fringes of scientific endeavor, research many explicitly avoided being identified with, especially those seeking government grants or academic tenure. That’s changed, though, as scientists have both discovered life in increasingly extreme environments on the Earth as well as identifying locales beyond Earth, including beyond our solar system, which may be hospitable to life. There are now astrobiology conferences, astrobiology journals, and even a NASA Astrobiology Institute. It’s in that environment of increased acceptance that Marc Kaufman surveys the state of astrobiology’s quest to discover life elsewhere in the universe in First Contact: Scientific Breakthroughs in the Hunt for Life Beyond Earth. Kaufman, a reporter for the Washington Post, covers a lot of ground in First Contact, both intellectually and geographically. For the book he traveled from mines in South Africa where scientists look for extremophiles living deep below the surface, to observatories in Chile and Australia where astronomers search for methane on Mars and planets around other stars, to conferences from San Diego to Rome where researchers discuss their studies. He uses this travel to provide a first-person account of the state of astrobiology today, neatly condensed into about 200 pages. It’s a good overview for those not familiar with astrobiology, although those who have been following the field, or at least some aspects of it, will likely desire more details than what’s included in this slender book. One interesting portion of the book looks at those people who still work in—or have been exiled to—the fringes of astrobiology even as the field gains wider acceptance. "[P]erhaps because of its urge for legitimacy, or because the discipline itself so often enters terra incognita, astrobiology has shown a consistent need to enforce a consensus," casting aside those who differ, Kaufman writes. These people include Gil Levin, who argues the Labeled Release experiment on the Viking landers did, in fact, detect life on Mars; David McKay, who led the team that discovered what they still believe is evidence of life in Martian meteorite ALH 84001; and Richard Hoover, who claims to see similar evidence for life in other meteorites. All three get fair, if somewhat sympathetic, profiles in one chapter of the book; Kaufman goes so far to lament that the three, presenting in the same session of a conference, draw only a handful of people—nevermind that they’re speaking at a conference run by SPIE, an organization better known for optics and related technologies. (Since the book went to press, Hoover has gained notoriety for publishing a paper in the quixotic, controversial Journal of Cosmology about his asteroid life claims, an event that generated some media attention but was widely rebuffed as containing nothing new to support his claims.) |

| Book |

First ContactScientific Breakthroughs in the Hunt for Life Beyond Earth  If it's just us in this universe, what a terrible waste of space. But it's not. Before the end of this century, and perhaps much sooner than that, scientists will determine that life exists elsewhere in the universe. This book is about how they're going to get there. And when they do, that discovery will rival the immensity of those that launched our previous sci entific revolutions and, in the process, defined our humanity. Copernicus and Galileo told us we were not, after all, at the center of the universe, and their ideas fathered a scientific astronomy that, four hundred years later, is allowing us to be a space-faring planet. Charles Darwin gave us our evo lutionary roots, which, a century later, propelled Louis and Mary Leakey on a thirty-year search culminating in the recovery of fossil hominid re mains almost two million years old in Tanzania's Olduvai Gorge — proof that humankind began in Africa. So here we are now, the descendants of the skilled toolmakers and explorers who left the continent some sixty to seventy thousand years ago. We've populated the globe and sent astronauts to the moon. Next up: Life beyond Earth. For thousands of years, humans have wondered about who and what might be living beyond the confines of our planet: gods, beneficent or angry, a heaven full of sinners long forgiven, creatures as large and strange as our imagination. Scientists now are on the cusp of bringing those mus ings back to Earth and recasting our humanity yet again. "Astrobiology" is the name of their young but fast-growing field, which immodestly seeks to identify life throughout the universe, partly by determining how it began on our planet. The men and women of astrobiology — an iconoclastic lot, quite unlike the caricatures of geeks in white lab coats or UFO-crazed con spiracy theorists — are driven by a confidence that extraterrestrial creatures are there to be found, if only we learn how to find them. Most hold the conviction that if a form of independently evolved life, even the tiniest mi crobe, is detected below the surface of Mars or Europa, or other moons of Jupiter or Saturn, then the odds that life does exist elsewhere in our galaxy and potentially in billions of others shoot up dramatically. A solar system that produces one genesis — ours — might be an anomaly. A single solar system that produces two or more geneses tells us that life can begin and evolve whenever and wherever conditions allow, and that extraterrestrial life may well be an intergalactic commonplace. |

| Article |

Not "Life," but Maybe "Organics" on Mars Thirty-four years after NASA's Viking missions to Mars sent back results interpreted to mean there was no organic material - and consequently no life - on the planet, new research has concluded that organic material was found after all. The finding does not bring scientists closer to discovering life on Mars, researchers say, but it does open the door to a greater likelihood that life exists, or once existed, on the planet. "We can now say there is organic material on Mars, and that the Viking organics experiment that didn't find any had most likely destroyed what was there during the testing," said Rafael Navarro-Gonzalez of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. "For decades NASA's mantra for Mars was 'follow the water' in the search for life, and we know today that water has been all over the planet," he said. "Now the motto is 'follow the organics' in the search for life." The original 1976 finding of "no organics" was controversial from the start because organic matter - complex carbons with oxygen and hydrogen, which are the basis of life on Earth - is known to fall on Mars, as onto Earth and elsewhere, all the time. Certain kinds of meteorites are rich in organics, as is the interstellar dust that falls from deep space and blankets planets. The new results, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Planets and highlighted Friday in a NASA news release, flow directly from a discovery made by NASA's Phoenix lander in 2008. |

| Article |

Ancient Meteorite Heats Up Martian Life-Form Debate LEAGUE CITY, Texas — NASA’s Mars Meteorite Research Team reopened a 14-year-old controversy on extraterrestrial life last week, reaffirming and offering support for its widely challenged assertion that a 4-billion-year-old meteorite that landed thousands of years ago on Antarctica shows evidence of microscopic life on Mars. The scientists reported that additional Martian meteorites appear to house distinct and identifiable microbial fossils that point even more strongly to the existence of life. "We feel more confident than ever that Mars probably once was, and maybe still is, home to life," team leader David McKay said at a NASA-sponsored conference on astrobiology. The researchers’ presentations were not met with any of the excited frenzy that greeted the original 1996 announcement about the meteorite — which led to a televised statement by President Bill Clinton in which he announced a "space summit," the formation of a commission to examine its implications and the birth of a NASA-funded astrobiology program. Fourteen years of relentless criticism have turned many scientists against the McKay results, and the Mars meteorite "discovery" has remained an unresolved and somewhat awkward issue. This has continued even though the team’s central finding — that Mars once had living creatures — has gained broad acceptance among the biologists, chemists, geologists, astronomers and other scientists who make up the astrobiology community. |

| Article |

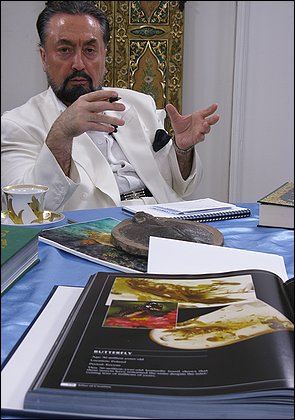

In Turkey, Fertile Ground for CreationismU.S. critics of evolution help translate their ideas for a society already torn between Islam and secularism.  ISTANBUL -- Sema Ergezen teaches biology to Turkish students interested in teaching science themselves, and she has long struggled with her students' ignorance of, and sometimes hostility to, the notion of evolution. But she was taken aback when several of her Marmara University students recently accused her of being an atheist, or worse, for teaching anything but the doctrine that God created the Earth and everything on it. "They said I was a liar if I called myself a Muslim because I also accepted evolution," she said. What especially disturbed -- and amused -- the veteran professor was that the arguments for creationism presented by some of the students came directly from the country where she was educated in the biological sciences years before -- the United States. Translated and adapted for a Muslim society, the purported proofs that Darwinism and evolution were wrong came directly from American proponents of Christian creationism and its less overtly religious offshoot, intelligent design. Ergezen's experience has become increasingly common. While creationism and intelligent design appear to be in some retreat in the United States, they have blossomed within Muslim Turkey. With direct and indirect help from American foes of evolution, similarly-minded Turks have aggressively made the case that Charles Darwin's theory is scientifically wrong and is the underlying source of most of the world's conflicts because it excludes God from human affairs. "Darwin is the worst Fascist there has ever been, and the worst racist history has ever witnessed," writes Harun Yahya, the most assertive and best-known critic of evolution in Turkey, and long a favorite of more conservative American creationists. The evolution-creationism battle is playing out against a backdrop of a much larger conflict between the forces of secularism -- as represented by the Turkish military and many of the country's more educated citizens -- and forces, including the popular ruling party, that want to make religion more important in national affairs. The Islamic anti-evolution campaign is taking place in Turkey, and not Egypt or Saudi Arabia, because it is the Muslim nation where evolution has been taken most seriously. Like the Bible, the Koran says that God created the Earth and everything on it, and in many Muslim nations that ends the discussion. But Turkey, which is officially secular, appears to be joining its Muslim neighbors on evolution. A recent survey, quoted in a 2008 article in the American journal Science, found that fewer than 25 percent of Turks accepted evolution as an explanation of how modern life |

| Article |

When E.T. Phones the PopeThe Vatican investigates all God's creatures, green and small.  ROME -- A little more than a half-mile from the Vatican, in a square called Campo de' Fiori, stands a large statue of a brooding monk. Few of the shoppers and tourists wandering through the fruit-and-vegetable market below may know his story; he is Giordano Bruno, a Renaissance philosopher, writer and free-thinker who was burned at the stake by the Inquisition in 1600. Among his many heresies was his belief in a "plurality of worlds" -- in extraterrestrial life, in aliens. Though it's a bit late for Bruno, he might take satisfaction in knowing that this week the Vatican's Pontifical Academy of Sciences is holding its first major conference on astrobiology, the new science that seeks to find life elsewhere in the cosmos and to understand how it began on Earth. Convened on private Vatican grounds in the elegant Casina Pio IV, formerly the pope's villa, the unlikely gathering of prominent scientists and religious leaders shows that some of the most tradition-bound faiths are seriously contemplating the possibility that life exists in myriad forms beyond this planet. Astrobiology has arrived, and religious and social institutions -- even the Vatican -- are taking note. Father Jose Funes, a Jesuit astronomer, director of the centuries-old Vatican Observatory and a driving force behind the conference, suggested in an interview last year that the possibility of "brother extraterrestrials" poses no problem for Catholic theology. "As a multiplicity of creatures exists on Earth, so there could be other beings, also intelligent, created by God," Funes explained. "This does not conflict with our faith because we cannot put limits on the creative freedom of God." Yet, as Bruno might attest, the notion of life beyond Earth does not easily coexist with the "truths" that many people hold dear. Just as the Copernican revolution forced us to understand that Earth is not the center of the universe, the logic of astrobiologists points |

| Review |

The Structure of EverythingDid we invent math? Or did we discover it?  Did you know that 365 -- the number of days in a year -- is equal to 10 times 10, plus 11 times 11, plus 12 times 12? Or that the sum of any successive odd numbers always equals a square number -- as in 1 + 3 = 4 (2 squared), while 1 + 3 + 5 = 9 (3 squared), and 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 = 16 (4 squared)? Those are just the start of a remarkable number of magical patterns, coincidences and constants in mathematics. No wonder philosophers and mathematicians have been arguing for centuries over whether math is a system that humans invented or a cosmic -- possibly divine -- order that we simply discovered. That's the fundamental question Mario Livio probes in his engrossing book Is God a Mathematician? Livio, an astrophysicist at the Hubble Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, explains the invention-vs.-discovery debate largely through the work and personalities of great figures in math history, from Pythagoras and Plato to Isaac Newton, Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein. At times, Livio's theorems, proofs and conundrums may be challenging for readers who struggled through algebra, but he makes most of this material not only comprehensible but downright intriguing. Often, he gives a relatively complex explanation of a mathematical problem or insight, then follows it with a "simply put" distillation. An extended section on knot theory is, well, pretty knotty. But it ultimately sheds light on the workings of the DNA double helix, and Livio illustrates the theory with a concrete example: Two teams taking different approaches to the notoriously difficult problem of how many knots could be formed with a specific number of crossings -- in this case, 16 or fewer -- came up with the same answer: 1,701,936.

The author's enthusiasm is infectious. But it also leads him to refer again and again to his subjects as "famous" and "great" and to their work as "monumental" and "miraculous." He has a weakness as well for extended quotes from these men (and they are all men) that slow the narrative without adding much. There are exceptions, including the tale of how he tale of how Albert Einstein and mathematician Oskar Morgenstern tried to guide Kurt Gödel, a fellow mathematician and exile from Nazi Germany, through the U.S. immigration process. A deep-thinking and intense man, Gödel threw himself into preparing for his citizenship test, including an extremely close reading of the U.S. Constitution. In his rigorously logical analysis, he found constitutional weaknesses that he thought could allow for the rise of a fascist dictatorship in America. His colleagues told him to keep that reading to himself, but he blurted it out during his naturalization exam. He was allowed to stay anyway. |

| Article |

Discoveries Out There Require Preparation Right Here Reports in 1996 that a meteorite from Mars that was found in Antarctica might contain fossilized remains of living organisms led then-Vice President Al Gore to convene a meeting of scientists, religious leaders and journalists to discuss the implications of a possible discovery of extraterrestrial life. Gore walked into the room armed with questions on notecards but, according to MIT physicist and associate provost Claude R. Canizares, he put them down and asked this first question: What would such a discovery mean to people of faith? There was silence, and then DePaul University president Jack Minogue, a priest, said: "Well, Mr. Vice President, if it doesn't sing and dance, we don't really have to worry much from a missionary point of view." Everyone had a good laugh, and then moved on to the serious business of exploring the consequences of such a historic and unsettling discovery -- a discussion that continued for two hours. Most scientists now discount the meteorite as evidence of Martian life, but preparing the public for a more definitive announcement continues. Several conferences and three major workshops have been held, the most recent sponsored by NASA, the John Templeton Foundation and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Its report, called "Philosophical, Ethical, and Theological Implications of Astrobiology," was published last year. "Any discovery of extraterrestrial life would raise some challenging questions -- about the origin of life on Earth as well as elsewhere, about the centrality of humankind in the universe, and about the creation story in the Bible," said Connie Bertka, a Unitarian minister with a background in Martian geology who ran the workshops for the AAAS. "The group felt strongly that the general public needs to know more about this whole subject and what astrobiology is trying to do," she said. Stephen J. Dick, NASA's chief historian and a member of the NASA-sponsored panel and another private effort, said he thinks that all the Abrahamic religions would have to adapt, "because the relationship of God and man is so central, and the idea that man was made in God's image and put on Earth is so strong." If life exists elsewhere, he said, then why would life on Earth be paramount to a creator? "A God that created the Earth and life on other Earths would still be majestic, but the logic of Him being someone to pray to and to get salvation from diminishes," he said. |

| Article |

Search for Alien Life Gains New ImpetusWhen Paul Butler began hunting for planets beyond our solar system, few people took him seriously, and some, he says, questioned his credentials as a scientist. That was a decade ago, before Butler helped find some of the first extra-solar planets, and before he and his team identified about half of the 300 discovered since. Biogeologist Lisa M. Pratt of Indiana University had a similar experience with her early research on “extremophiles”, bizarre microbes found in very harsh Earth environments. She and colleagues explored the depths of South African gold mines and, to their great surprise, found bacteria sustained only by the radioactive decay of nearby rocks. “Until several years ago, absolutely nobody thought this kind of life was possible—it hadn’t even made it into science fiction,” she said. “Now it’s quite possible to imagine a microbe like that living deep beneath the surface of Mars.” |

| Discussion |

Searching for Extraterrestrial LifeWashington Post staff writer Marc Kaufman and planet-hunter Paul Butler went online to discuss the search for alien life. Washington Post staff writer Marc Kaufman and planet-hunter Paul Butler were online Monday, July 21 at 11 a.m. ET to discuss the search for alien life. Butler, who discovered some of the first extra-solar planets, will be joining the discussion from the Keck Observatory in Hawaii after a night of sky gazing. Kaufman notes in his story, Search for Alien Life Gains New Impetus, that there is an explosion taking place in astrobiology, in part because of NASA’s Phoenix landing on Mars. "Few believe that the discovery of extraterrestrial life is imminent," writes Kaufman, "However, just as scientists long theorized that there were planets orbiting other stars—but could not prove it until new technologies and insights broke the field wide open—many astrobiologists now see their job as to develop new ways to search for the life they are sure is out there." |

| Article |

Researchers Say Stonehenge Was a Burial GroundConclusion Runs Counter to Long-Held Theories  The secret of Stonehenge has apparently been solved: The mysterious circle of large stones in southern England was primarily a burial ground for almost five centuries, and the site probably holds the remains of a family that long ruled the area, new research concludes. Based on radiocarbon dating of cremated bones up to 5,000 years old, researchers with the Stonehenge Riverside Project said they are convinced the area was built and then grew as a "domain of the ancestors." "It's now clear that burials were a major component of Stonehenge in all its main stages," said Mike Parker Pearson, an archaeology professor at the University of Sheffield in England and head of the project. "Stonehenge was a place of burial from its beginning to its zenith in the mid-third millennium B.C." The finding marks a significant rethinking of Stonehenge. In the past it was believed that some burials took place there for a century but that the site's significance lay in its ceremonial and religious functions, including serving as a center for healing. A combination of the radiocarbon dating, excavations nearby that have revealed a once-thriving village and the fact that the number of cremated remains appeared to grow over a 500-year period convinced researchers that the site was used for a long time and most likely was a burial ground for one ruling family. Parker Pearson said the discovery of a mace head -- the enlarged end of a clubbing weapon -- supports the theory that it was the province of a ruling family since it was long a symbol of authority in England and still serves that function in the House of Commons. |