Mark Vernon

Mark Vernon writes regularly for the Guardian, Financial Times, Times Literary Supplement,Management Today, and Philosophers' Magazine, among many other publications. He broadcasts from a variety of news outlets, including BBC Radio 2, Radio 3, Radio 4, Five Live, BBC Radio London, BBC TV, and ABC Radio National. His books include After Atheism: Science, Religion, and the Meaning of Life; The Philosophy of Friendship; 42: Deep Thought on Life, the Universe, and Everything. His most recent book, Teach Yourself Humanism, will be published later this year.

| Article |

Why We're All FundamentalistWhen did faith stop being about trust, and become a set of propositions to be believed? Mark Vernon looks back in history for clues to the fundamentals that fire a true life passion for people.  There is a story about Socrates, in which the sage of Athens is looking back on his life1. He recalls one day sitting with Plato, in the days of his great disciple's youth. Plato is talking. Socrates is watching him. He can see the freckles on Plato's face, his intelligent eyes, his seriousness, his confidence. Suddenly, Socrates is struck by a thought: 'I knew that if an archer were to shoot at him, I would step in front of him without hesitating and I'd take the arrow in my chest.' He knew this without a doubt. And then came a feeling that surprised him. 'I was smiling because I was truly happy.' Human beings are all, in a sense, fundamentalists. Or at least, we might all hope to be so - an individual who knows who they would die for; what they would die for. It will be a person or belief so essential, so sacred, that sacrificing for it would not so much end your life as show your life has an end, in the sense of a goal, a reason, a meaning. Further, knowing what you would die for means that you know what you live for. There is nothing that makes life more worth living; it generates purpose, commitment, love. It is liberating too. If you know you could let go of life, you can live more freely now. Socrates smiled. He was happy. Fundamentalism, though, is different. In its rarer, violent forms it is a basic conviction about life too, though gone wrong. Love reveals what you would die for. But the passions of hatred and war can do so too, as the jihadis learnt in the Afghan conflicts of the last decades of the 20th century. Further, this kind of fundamentalism is not so much about what you would die for as what you would kill for. |

| Column |

Can Evolutionary Theorists Ever Make Sense of Religion?A new theory disregards the dominant evolutionary story, and explores instead religion's origins in playtime and ritual.  The currently dominant evolutionary story for the origin of religions might be called the "byproduct theory". It goes something like this. The human brain evolved a series of cognitive modules, a bit like a smartphone downloading applications. One was good for locomotion, another seeing, another empathy, and so on. However, different modules could interfere with one another, called "domain violation" in the literature. The app for locomotion might overrun the app for empathy and, as a result, the hapless owner of that brain might discern a spirit shifting in the rustling trees, because the branches sway a little like limbs moving. The anthropologist Pascal Boyer calls such interpretations "minimally counterintuitive". They can't be too random or they wouldn't grip your imagination. But, clearly, they are not rational. Religion is, therefore, a cognitive mistake. It might once have delivered adaptive advantages: swaying branches could indicate a stalking predator, and so you'd be saved if you fled, even if you believed the threat was a ghost. But rational individuals such as, say, evolutionary theorists now see religious beliefs for what they really are. Given that this is the story that often does the rounds, it is striking that Robert Bellah's new book, "Religion in Human Evolution," has no time for it whatsoever. Literally. Look up "Boyer" in the index and you are led to a footnote. "I have found particularly unhelpful those who think of the mind as composed of modules and of religion as explained by a module for supernatural beings," Bellah remarks. They have a "tendency toward speculative theorizing and [a] lack of insight into religion as actually lived". In short, the story is neither convincing when it comes to cognition, nor when it comes to describing religious practice. Bellah's judgment matters because he is a venerable sociologist of religion who takes evolution seriously: it can be revealing about the nature of religion, he insists, though only if you are talking about religions as they actually exist. So what goes wrong? A fundamental mistake, Bellah argues, is to conceive of religion as primarily a matter of propositional beliefs. It is not just that this is empirically false. There are good evolutionary reasons for understanding religion in an entirely different way, too. Go back deep into evolutionary time, long before hominids, Bellah invites his readers, because here can be found the basic capacity required for religion to emerge. It is mimesis or imitative action, when animals communicate their intentions, often sexual or aggressive, by standard behaviours. Often such signals seem to be genetically determined, though some animals, like mammals, are freer and more creative. It can then be called play, meant in a straightforward sense of "not work", work being activity that is necessary for survival. |

| Column |

We Can't Forgive, We Can Only Pretend ToEvolutionary doctrine teaches us that it's in our own self-interest to co-operate and to put up with others.  Forgiveness is impossible. This was the thought of the philosopher Jacques Derrida, and he has a good point. There are some things that we say are easy to forgive. But, Derrida argues, they don't actually need forgiving. I forget to reply to an email, and my friend remarks: "Oh, it didn't really matter anyway." It's not that he forgave me. He'd forgotten about the email too. Then, there are other things we say are hard to forgive, and we admire those who appear to be able to forgive nonetheless. The case of Rais Bhuiyan, who was shot by Mark Stroman, is a case in point. Bhuiyan says he forgave Stroman, and asked the Texas authorities not to execute him for his crime. But did Bhuiyan really forgive? He writes of how Stroman was ignorant and had a terrible upbringing. He had seen signs that Stroman was now a changed man. So, it does not seem that Bhuiyan forgave his assailant. Rather, he came to understand him. He saw the crime from the perpetrator's point of view. There were reasons for the wrongdoing. That lets Stroman off the hook. It's not really forgiveness. CS Lewis wrote: "Everyone says forgiveness is a lovely idea, until they have something to forgive." Which is again to imply that those who think they have offered forgiveness really find they don't have anything to forgive after all. The ancient philosophers appear to have thought that forgiveness is something of a pseudo-subject, too. They hardly touched on it, for all that they dwelt on all manner of other moral concerns. It is not on any list of virtues. Take Aristotle. He wrote about pardoning people, but only when they are not responsible. "There is pardon," he says, "whenever someone does a wrong action because of conditions of a sort that overstrain human nature, and that no one would endure." When nature has not been overstrained, justice must meet wrongdoing. Forgiveness doesn't come into it. All this calls into question a theory in evolutionary psychology. Here, the argument is that forgiveness is essential to our evolutionary success. It's because we forgive one another that we are able to live in large groups. People in collectives like cities are bound to offend one another all the time, the theory goes. It's because we are so ready to forgive and continue to co-operate that we don't, as a rule, destroy ourselves in spirals of retribution. |

| Column |

Carl Jung, Part 8: Religion and the search for meaningJung thought psychology could offer a language for grappling with moral ambiguities in an age of spiritual crisis.  In 1959, two years before his death, Jung was interviewed for the BBC television programme Face to Face. The presenter, John Freeman, asked the elderly sage if he now believed in God. "Now?" Jung replied, paused and smiled. "Difficult to answer. I know. I don't need to believe, I know." What did he mean? Perhaps several things. He had spent much of the second half of his life exploring what it is to live during a period of spiritual crisis. It is manifest in the widespread search for meaning – a peculiar characteristic of the modern age: our medieval and ancient forebears showed few signs of it, if anything suffering from an excess of meaning. The crisis stems from the cultural convulsion triggered by the decline of religion in Europe. "Are we not plunging continually," Nietzsche has the "madman" ask when he announces the death of God. "Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us?" Jung read Nietzsche and agreed that it was. The slaughter of two world wars and, as if that were not enough, the subsequent proliferation of nuclear weaponry were signs of a civilisation swept along by unconscious tides that religion, like a network of dykes, once helped contain. "A secret unrest gnaws at the roots of our being," he wrote, an unrest that yearns for the divine. Nietzsche agreed that God still existed as a psychic reality too: "We godless anti-metaphysicians still take our fire … from the flame lit by a faith that is thousands of years old." And now the flame is out of control. The sense of threat – real and imagined – that Jung witnessed during his lifetime has not lessened. Ecologists such as James Lovelock now predict that the planet itself has turned against us. Or think of the war games that power an online gaming industry worth £45bn and counting. Why do so many spend so much indulging murderous fantasies? You could also point to the proliferation of new age spiritualities that take on increasingly fantastical forms. One that interested Jung was UFOs: the longing for aliens – we are without God but not without cosmic companions – coupled to tales of being "chosen" for abduction, are indicative of mass spiritual hunger. |

| Column |

Carl Jung, part 7: The power of acceptanceLike the AA movement, Jung believed that acceptance and spiritual interconnectedness were crucial to a person's recovery.  In 1931, one of Jung's patients proved stubbornly resistant to therapy. Roland H was an American alcoholic whom he saw for many weeks, possibly a year. But Roland's desire for drink refused to diminish. A year later Roland returned to Zürich still drinking, and Jung concluded that he probably wouldn't be cured through therapy. But ever the experimenter, Jung had an idea. Roland should join the Oxford Group, an evangelical Christian movement that stressed the necessity of total surrender to God. Jung hoped that his patient might undergo a conversion experience, which, as his friend William James had realised, is a transformative change at depth, brought about by the location of an entirely new source of energy within the unconscious. That might tame the craving. It worked. Roland told another apparently hopeless alcoholic, Bill W, about the experience. Bill too was converted, and had a vision of groups of alcoholics inspiring each other to quit. The Society of Alcoholics Anonymous was formed. Today it has more than 2 million members in 150 countries. I spoke to a friend of mine who attends meetings of Narcotics Anonymous to understand more about the element of conversion. "It's hugely important," he said. His addictions had been fuelled by a surface obsession with career and money, and a deeper anxiety that nothing was right. "It's the first time I'd been prompted seriously to consider something bigger than myself." Calling the experience "spiritual" seems accurate too, because a meeting is about more than gaining a circle of supportive friends. "I have friends," my friend remarks, before continuing that the focused intention of a meeting is about something else: their connection to a very powerful force. "I can't picture it, I can't name it," he says, before adding, "I've never given much thought to church." Narcotics Anonymous literature expresses it more formally: "For our group purpose there is but one ultimate authority – a loving God as He may express Himself in our group conscience." |

| Column |

Carl Jung, Part 6: SynchronicityWith physicist Wolfgang Pauli, Jung explored the link between the disparate realities of matter and mind.  The literary agent and author Diana Athill describes the genesis of one of her short stories. It occurred about nine one morning, when she was walking her dog. Crossing the road, a car approached and slowed down. She presumed someone needed directions. A man leaned out and brazenly asked her whether she would like to join him for coffee. That was odd enough, so early in the day. More oddly still, the man powerfully reminded her of someone else. He looked just like a lost friend and, further, the daring approach was just the kind of thing her friend would have done. She couldn't stop thinking about the coincidence. It left her feeling " energised and strange," a flow that kept bubbling up until she channelled it, producing the short story. It is an example of what Jung called synchronicity, "a coincidence in time of two or more causally unrelated events which have the same or similar meaning" – in Athill's case, the surprising invitation of the man and his looking like her friend. Anecdotally, it seems that such experiences are familiar to many. They are undoubtedly meaningful and produce tangible effects too, like short stories. But they raise a question: is the relationship between the events random or is some hidden force actively at work? Jung pursued this question in an odd relationship of his own, with one of the great physicists of the 20th century, Wolfgang Pauli. The story of their friendship is related by Arthur I Miller, in "137: Jung, Pauli, and the Pursuit of a Scientific Obsession." Pauli was a Jekyll and Hyde character, a Nobel theorist by day and sometime drunk womaniser by night. He turned to Jung when he could no longer hold the competing aspects of his life together. Jung was always fascinated by personality splits, and his analysis helped to steady Pauli. They began working together in a collaboration that lasted for several decades, though mostly behind closed doors: Pauli worried for his reputation, though eventually they published a book together. |

| Column |

If You Want Big Society, You Need Big ReligionFaith communities may encourage their members to contribute to society – but can politicians harness their benefits?  Robert Putnam, Harvard professor of public policy, has been in London, channelling the wisdom of social capital at No 10, as well as talking at St Martins-in-the-Fields on Monday evening. That venue is the big clue to his latest findings. It could be summarised thus: if you want big society, you need big religion. In the US, over half of all social capital is religious. Religious people just do all citizenish things better than secular people, from giving, to voting, to volunteering. Moreover, they offer their money and time to everyone, regardless of whether they belong to their religious group. It could be, of course, that the religious already have the virtues of citizenship. However, Putnam believes the relationship is causal, not just a correlation. Longitudinal studies also show as much. So why? He argues it's not to do with belief, but with being part of a community of belief. An atheist with several churchgoing friends will be a better citizen too. In fact, churchgoing friends are what he calls "supercharged" when it comes to citizenship. Working out just what a religious community gives would be key to generalising the findings beyond faith. |

| Column |

Carl Jung, Part 4: Do Archetypes Exist?Jung's theory of structuring principles remains controversial--but provides a language to talk about shared experience  Jung took the inner life seriously. He believed that dreams are not just a random jumble of associations or repressed wish fulfilments. They can contain truths for the individual concerned. They need interpreting, but when understood aright, they offer a kind of commentary on life that often acts as a form of compensation to what the individual consciously takes to be the case. A dream Jung had in 1909 provides a case in point. He was in a beautifully furnished house. It struck him that this fine abode was his own and he remarked, "Not bad!" Oddly, though, he had not explored the lower floor and so he descended the staircase to see. As he went down, the house got older and darker, becoming medieval on the ground floor. Checking the stone slabs beneath his feet, he found a metal ring, and pulled. More stairs led to a cave cut into the bedrock. Pots and bones lay scattered in the dirt. And then he saw two ancient human skulls, and awoke. Jung interpreted the dream as affirming his emerging model of the psyche. The upper floor represents the conscious personality, the ground floor is the personal unconscious, and the deeper level is the collective unconscious – the primitive, shared aspect of psychic life. It contains what he came to call archetypes, the feature we shall turn to now. They are fundamental to Jung's psychology. Archetypes can be thought of simply as structuring principles. For example, falling in love is archetypal for human beings. Everyone does it, at least once, and although the pattern is common, each time it feels new and inimitable. |

| Column |

Human Consciousness is Much More than Mere Brain ActivityWhen we meditate or use our powers of perception, we call on more than just a brain.  How does the animated meat inside our heads produce the rich life of the mind? Why is it that when we reflect or meditate we have all manner of sensations and thoughts but never feel neurons firing? It's called the "hard problem", and it's a problem the physician, philosopher and author Raymond Tallis believes we have lost sight of – with potentially disastrous results. In his new book, Aping Mankind – about which he was talking this week at the British Academy – he describes the cultural disease that afflicts us when we assume that we are nothing but a bunch of neurons. Neuromania arises from the doctrine that consciousness is the same as brain activity or, to be slightly more sophisticated, that consciousness is just the way that we experience brain activity. If you think the brain is a machine then you are committed to saying that composing a sublime poem is as involuntary an activity as having an epileptic fit. You will issue press releases announcing "the discovery of love" or "the seat of creativity", stapled to images of the brain with blobs helpfully highlighted in red or blue, that journalists reproduce like medieval acolytes parroting the missives of popes. You will start to assume that the humanities are really branches of biology in an immature form. What is astonishing about this rampant reductionism is that it is based on a conceptual muddle that is readily unpicked. Sure, you need a brain to be alive, but to be human is not to be a brain. Think of it this way: you need legs to walk, but you'd never say that your legs are walking. The same conflation can be exposed in a more complex way by reflecting on the phenomenon of perception. It is what we do every moment of the waking day. You're doing it right now: casting an eye to the paper in front of you and seeing words on a page. But if you were just a brain, you would not see words. There'd be just the gentle buzz of neuronal activity in the intracranial darkness. |

| Column |

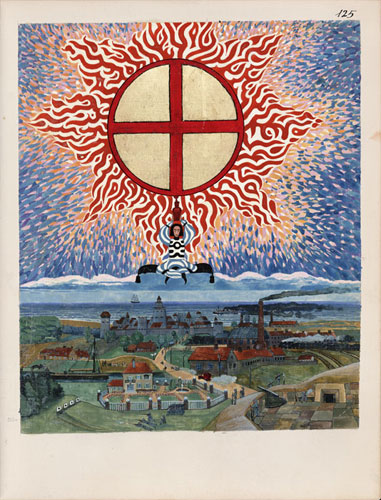

Carl Jung, Part 3: Encountering the UnconsciousJung's Red Book reveals his belief in the painful, personal process of discovering how the unconscious manifests itself in conscious life  Jung's split with Freud in 1913 was costly. He was on his own again, an experience that reminded him of his lonely childhood. He suffered a breakdown that lasted through the years of the first world war. It was a traumatic experience. But it was not simply a collapse. It turned out to be a highly inventive period, one of discovery. He would later say that all his future work originated with this "creative illness". He experienced a succession of episodes during which he vividly encountered the rich and disturbing fantasies of his unconscious. He made a record of what he saw when he descended into this underworld, a record published in 2009 as The Red Book. It is like an illuminated manuscript, a cross between Carroll's Alice in Wonderland and Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Its publication sparked massive interest in Jungian circles, rather like what happens in Christian circles when a new first-century codex is discovered. It is of undoubted interest to scholars, in the same way that the notebooks of Leonardo are to art historians. And it is an astonishing work to browse, for its intricacy and imagination. But it is also highly personal, which is presumably why Jung decided against its publication in his own lifetime. So, to turn it into a sacred text, as some appear inclined to do, would be a folly of the kind Jung argued against in the work that followed his recovery from the breakdown. In particular he wrote two pieces, known as the Two Essays, that provide a succinct introduction to his mature work. (He can otherwise be a rambling, elusive writer.) On the Psychology of the Unconscious completes his separation from Freud. He shows how tracing the origins of a personal crisis back to a childhood trauma, as Freud was inclined to do, might well miss the significance of the crisis for the adult patient now. In The Relations between the Ego and the Unconscious, he describes a process whereby a person can pay attention to how their unconscious life manifests itself in their conscious life. It will be a highly personal and tortuous experience. "There is no birth of consciousness without pain," he wrote. But with it, the individual can become more whole. By way of illustration, Jung considers the example of a man whose public image is one of honour and service but who, in the privacy of his home, is prone to moods – so much so that he scares his wife and children. He is leading a double life as public benefactor and domestic tyrant. Jung argues that such a man has identified with his public image and neglected his unconscious life – though it won't be ignored and so comes out, with possibly explosive force, in his relations with his family. The way forward is to pay attention to this inner personality, literally by holding a conversation with himself. He should overcome any embarrassment in doing so and allow each part of himself to talk to the other so that both "partners" can be fully heard. |

| Column |

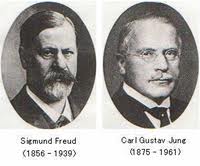

Carl Jung, part 2: A troubled relationship with Freud – and the NazisOn the 50th anniversary of Jung's death it is time to put accusations of him collaborating with the Nazis to rest.  Jung's relationship with Freud was ambivalent from the start. First contact was made in 1906, when Jung wrote about his word association tests, realising that they provided evidence for Freud's theory of repression. Freud immediately and enthusiastically wrote back. But Jung hesitated. It took him several months to write again. They met a year later and then it was friendship at first sight. The two talked non-stop for 13 hours. Freud called Jung "the ablest helper to have joined me thus far", and spoke of how Jung would be good for psychoanalysis as he was a respected scientist and a protestant – a dark observation that was to haunt Jung three decades later when the Nazis came to power. For now, different tensions persisted. A request Jung made highlights one axis of difficulty: "Let me enjoy your friendship not as one between equals but as that of father and son," he wrote. The originator of the Oedipus situation, in which murderous undertones supposedly exist between a father and a son, was alarmed. Freud did anoint Jung his "son and heir", but he also experienced a series of neurotic episodes revealing the fear that Jung was a threat too. One such incident occurred when they travelled together to America in 1909. Conversation turned to the subject of the mummified corpses found in peat bogs, which prompted Freud to accuse Jung of wanting him dead. He then fainted. A similar thing happened again a while later. A different sign of conflict came when Jung asked Freud what he made of parapsychology. Sigmund was a complete sceptic: occult phenomena were to him a "black tide of mud". But as they were sitting talking, Jung's diaphragm began to feel hot. Suddenly, a bookcase in the room cracked loudly and they both jumped up. "There, that is an example of a so-called catalytic exteriorisation phenomenon," Jung retorted – referring to his theory that the uncanny could be projections of internal strife. "Bosh!" Freud retorted, before Jung predicted that there would be another crack, which there was. All in all, from early on, Jung was nagged by the thought that Freud placed his personal authority above the quest for truth. And behind that lay deep theoretical differences between the two. |

| Column |

Carl Jung, Part 1: Taking Inner Life SeriouslyAchieving the right balance between what Jung called the ego and self is central to his theory of personality development.  If you have ever thought of yourself as an introvert or extrovert; if you've ever deployed the notions of the archetypal or collective unconscious; if you've ever loved or loathed the new age; if you have ever done a Myers-Briggs personality or spirituality test; if you've ever been in counselling and sat opposite your therapist rather than lain on the couch – in all these cases, there's one man you can thank: Carl Gustav Jung. The Swiss psychologist was born in 1875 and died on 6 June 1961, 50 years ago next week. His father was a village pastor. His grandfather – also Carl Gustav – was a physician and rector of Basel University. He was also rumoured to be an illegitimate son of Goethe, a myth Carl Gustav junior enjoyed, not least when he grew disappointed with his father's doubt-ridden Protestantism. Jung felt "a most vehement pity" for his father, and "saw how hopelessly he was entrapped by the church and its theological teaching", as he wrote in his autobiographical book, Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Jung's mother was a more powerful figure, though she seems to have had a split personality. On the surface she came across as a conventional pastor's wife, but she was "unreliable", as Jung put it. She suffered from breakdowns. And, differently again, she would occasionally speak with a voice of authority that seemed not to be her own. When Jung's father died, she spoke to her son like an oracle, declaring: "He died in time for you." In short, his childhood was disturbed, and he developed a schizoid personality, becoming withdrawn and aloof. In fact, he came to think that he had two personalities, which he named No 1 and No 2. No 1 was the child of his parents and times. No 2, though, was a timeless individual, "having no definable character at all – born, living, dead, everything in one, a total vision of life". (At school, his peers seem to have picked this up, as his nickname was "Father Abraham".) |

| Column |

Too Much Heat, Not Enough Light in the Creationism WarThe near hysterical way in which intelligent design is treated online only suits those who seek to politicise evolution.  The most dismaying feature of the rise of creationism and intelligent design (ID) in the present day is the success advocates have in distorting so much of the wider public discussion of evolution. In short, evolution has become as much a political question as one of modern science. Culture wars, over the place of religion in society, show no sign of lessening. And so sadly it seems that creationism and ID will remain strong too, because what sustains them is not any serious contribution to science or theology, but precisely the heat of dispute. For example, last week I was talking with a senior biochemist at Cambridge University. He reported that he could not recall a single mention of the word "creationism" during the time he worked in Turkey, which was for much of the 1970s. Nowadays though, it dominates the discussion at a public level – thanks to the activities of individuals like Harun Yahya, whose polemical and widely distributed books, such as The Atlas of Creation, advocate old Earth creationism. At least this can be tackled head-on, for the very reason that it is out in the open. Many in the Muslim world are now doing so. I was also fortunate enough to speak with Rana Dajani last week, a Jordanian molecular biologist. She believes part of the problem is that Darwin was only recently translated into Arabic, and so many people do not have access to quality information about evolution. They only have the polemic and the politics. It's a deficit she, for one, is working hard to put right. But the insidious effects of the culture clashes run deeper too. Consider the current case of the academic journal, Synthese. Synthese is a well-respected philosophy publication, with past contributors including Thomas Nagel and Jerry Fodor. It recently had a guest-edited special issue on "Evolution and Its Rivals". One article in this issue included a critique of the work of Francis Beckwith, a professor at Baylor University. If I tell you that last month he gave a talk entitled, "No God, No Good: Why the Moral Law Requires a Moral Lawgiver", you can see where he's coming from. Allegedly, friends of Beckwith complained at the personal nature of the published critique. |

| Column |

Tunisians' Welcoming of Libyan Refugees is Altruism in ActionTunisian willingness to house fleeing Libyans reminds us that caring for others is really a human, not a technical, act.  Many tens of thousands of refugees have now fled Libya and crossed to the relative safety of Tunisia. Their stories will, no doubt, be ones of terror and horror. And yet, there are tales of deep humanity too in their flight. A UNHCR spokesperson, Andrej Mahecic, has reported that fewer than one in ten of the Libyan arrivals are staying in refugee camps. Instead, the vast majority of those fleeing have been welcomed by Tunisian communities. The homeless Libyans are being hosted by locals, at the locals' expense and with great generosity, given the Tunisians' own resources are not great. It's a moving tale, especially given the worries rattling around rich Europe about the migration implications of the Arab uprisings, given our own habits of locking up immigrants behind bars. Of course, the situation in Libya is an emergency. And there are deep bonds between these peoples, founded upon a common religion. But the story prompts thoughts about the nature of altruism and what happens when caring for others comes to be seen as primarily a technical, rather than a human, problem. There is a lot of discussion about altruism today, driven in large part by the trouble it causes evolutionary theory. In the dog-eat-dog world of crude Darwinism, why should it be that some species collaborate, even to the point of self-sacrifice? In fact, Martin Nowak, author of SuperCooperators, argues that co-operation is quite as central to evolution as competition. You only need do the maths, he explains, the cost-benefit analysis. Working together in groups works. Only, that's not the whole story, he continues. |

| Column |

Tunisia, Libya, and FreedomTunisian willingness to house fleeing Libyans reminds us that caring for others is really a human, not a technical, act.  Many tens of thousands of refugees have now fled Libya and crossed to the relative safety of Tunisia. Their stories will, no doubt, be ones of terror and horror. And yet, there are tales of deep humanity too in their flight. A UNHCR spokesperson, Andrej Mahecic, has reported that fewer than one in ten of the Libyan arrivals are staying in refugee camps. Instead, the vast majority of those fleeing have been welcomed by Tunisian communities. The homeless Libyans are being hosted by locals, at the locals' expense and with great generosity, given the Tunisians' own resources are not great. It's a moving tale, especially given the worries rattling around rich Europe about the migration implications of the Arab uprisings, given our own habits of locking up immigrants behind bars. Of course, the situation in Libya is an emergency. And there are deep bonds between these peoples, founded upon a common religion. But the story prompts thoughts about the nature of altruism and what happens when caring for others comes to be seen as primarily a technical, rather than a human, problem. There is a lot of discussion about altruism today, driven in large part by the trouble it causes evolutionary theory. In the dog-eat-dog world of crude Darwinism, why should it be that some species collaborate, even to the point of self-sacrifice? In fact, Martin Nowak, author of SuperCooperators, argues that co-operation is quite as central to evolution as competition. You only need do the maths, he explains, the cost-benefit analysis. Working together in groups works. Only, that's not the whole story, he continues. The problem with a cost-benefit analysis approach is that it reduces altruism. Instead of being about selflessness, it becomes a new form of selfishness. I'll scratch your back if you scratch mine. Maybe not today. Maybe not tomorrow. But I'll remember what I did for you, and hold you forever in my debt. Transfer that into the moral discourse that shapes a culture, and you find yourself with a world in which virtues such as trust, courage, loyalty and sympathy struggle to thrive. Instead of honour, we write contracts. Instead of bonds of friendship, we work out our relationship to one another in the courts. Nowak recognises that the maths can provide only half the story, and it misses out the most important part too, namely the role played by intention. What are the values that underpin co-operation? What are the beliefs that allow it to flourish? This is the vital discussion, he asserts, and one that must include politicians and philosophers, artists and theologians, alongside the scientists. |

| Review |

The Final Testament of the Holy Bible is Shocking. Shockingly Bad, that is.The problem with James Frey's book isn't blasphemy per se. Good blasphemy, unlike this adolescent theology, is valuable.  Blasphemy is in the news again, and this time it has nothing to do with the Qu'ran or the prophet Muhammad. The novelist James Frey has written a new life of Jesus, The Final Testament of the Holy Bible. It is set in contemporary New York in which a Jesus-figure, Ben, comes back among New York lowlife, as lowlife. His message is the old hippy one – love, love, love – which he pursues in very practical ways. He makes love to almost everyone he meets – women, men, drug addicts, priests. Hence the blasphemy. Or at least, that is what the publishers are hoping. Written on the cover, in bold, we are told that this is Frey's most revolutionary and controversial work. "Be moved, be enraged, be enthralled by this extraordinary masterpiece," it screams in uppercase letters. I hope people don't rise to the bait. The book is more ludicrous than scandalous. The rabbit-like lovemaking is accompanied by dialogue of the "we-screwed-until-dawn-and-it-was-like-being-joined-with-the-cosmos" type. And then there's the adolescent protest theology. Religion is responsible for all ills everywhere, Ben solemnly informs us. The Bible is a stone age sci-fi text. God is no more believable than fairies. Faith is just an excuse to oppress. That said, the book did set me thinking about blasphemy. For it seems to me that there is good blasphemy and bad blasphemy. Good blasphemy is worth studying, whereas bad blasphemy is not. Good blasphemy conveys ethical and theological insights, whereas bad blasphemy is simply about complaint and shock. Both kinds of blasphemy might be published, but only the good type is worth spending time on. (It's a shame when bad blasphemy upsets believers and gains press coverage that encourages others to react to it.) I was myself involved in a blasphemy case, one of the last to be investigated by the police before changes in British law. We'd published a banned poem, The Love that Dares to Speak its Name by James Kirkup. It strikes me now that while there were important principles of free speech to defend in the case, the poem itself is an example of bad blasphemy. It features a Roman centurion having sex with Jesus after his crucifixion, and is naive and clumsy, replete with ban puns about Jesus being "well hung". Aesthetically it's inept, ethically it's simplistic, theologically it's crass. |

| Column |

Martin Rees's Templeton Prize May Mark a Turning Point in the "God Wars"Awarding the Templeton prize to Rees suggests science is rejecting the advocacy of the likes of Richard Dawkins  Richard Dawkins – author of The God Delusion and theorist of the selfish gene – could claim to be the most famous scientist in Britain. Sir Martin Rees – astronomer royal, former president of the Royal Society, master of Trinity College, Cambridge – is arguably the most distinguished. Last year, Dawkins published an ugly outburst against the softly spoken astronomer, calling him a "compliant Quisling" because of his views on religion. And now, Rees has seemingly hit back. He has accepted the 2011 Templeton prize, awarded for making an exceptional contribution to investigating life's spiritual dimension. It is worth an incongruous $1.6m. Dawkins is no stranger to pungent rhetoric when it comes to religion. But "Quisling" is strong even by his standards. It was originally hurled against fascist collaborators during the second world war. Rees, a collaborator? What was the crime that warranted such approbation? The Royal Society lent its prestige to the Templeton Foundation by hosting events sponsored by the fund, which supports a variety of projects investigating the science of wellbeing and faith. Dawkins and Rees differ markedly on the tone with which the debate between science and religion should be conducted. Dawkins devotes his talents and resources to challenging, questioning and mocking faith. Rees, on the other hand, though an atheist, values the legacy sustained by the church and other faith traditions. He confesses a liking for choral evensong in the chapel of Trinity College. It seems a modest indulgence. The ethereal voices of rehearsing choristers can literally be heard from his front door. But for Dawkins this makes the man a "fervent believer in belief". And that is a foul betrayal of science. I should declare an interest here, as I too would be what Dawkins calls an "accommodationist", (when he is being polite). I often write about the relationship between science and religion, and have been a Templeton-Cambridge Journalism Fellow, the beneficiary of a first-rate seminar programme organised by Cambridge academics, funded by the Templeton Foundation. But then I love the big questions. |

| Article |

Are Humans Hard-Wired for God?Some scientists suggest that a belief in God is part of human instinct; others argue that God is a human invention. Mark Vernon looks at the evidence.  MOST human beings, even in the modern world, believe in God or gods. The World Religion Database suggests that at least three-quarters of the world’s population identify with a theistic religion. Conversely, only two per cent are atheists. It is a phenomenon that researchers in the field of cognitive science are investigating, with results that might be thought unsettling for believers. One way to ask why humans believe in God is to study children. The University of Oxford’s Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology and its Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology has been given a three-year, $3.9-million grant by the John Templeton Foundation to explore exactly this. The psychologist Dr Justin Barrett has concluded that, when young, we are inclined to believe in a kind of natural religion. Children assume that there are divinities who act as agents in the world —which is to say, there are purposive forces abroad in the cosmos. These "God concepts" are associated in the child’s mind with a number of characteristics. A common one is that the world is designed — and in particular, that it is designed for the child concerned. Children will also explain features of the world around them in ways that adults do not teach them. "For instance," Dr Barrett says, "children are inclined to say rocks are ‘pointy’ not because of some physical processes but because being pointy keeps them from being sat upon." Children are also likely to ascribe theological attributes to their view of God. Take a child aged five. He or she knows that, say, there are no corn flakes left in the packet, because of having shaken it. The child will also comprehend that Mummy is wrong when, at breakfast, having put the packet on the table, she insists, "You’ve got the cornflakes." But the child will also understand that God knows that there are no cornflakes left, even though God has not shaken the packet —because, by that age, the child will also assume that God knows everything. |

| Column |

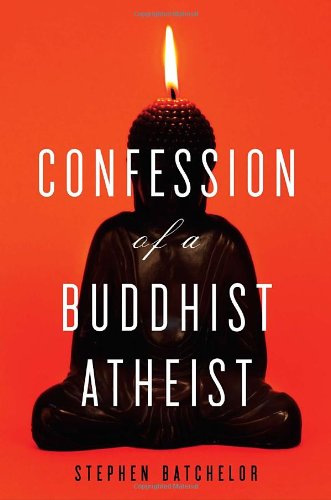

Buddhism is the New Opium of the PeopleWestern Buddhism has a long path to travel before becoming something that resists, rather than supplements, consumerism.  In one of the many living rooms that belong to David and Victoria Beckham, there sits a four-feet-high golden statue of the Buddha. Madeleine Bunting spotted it on TV, she told a packed audience for the last of the Uncertain Minds series. What is it about Buddhism, she mused, that makes it such a perfect fit with modern consumerism? The Buddhist writer Stephen Batchelor who, along with the Buddhist scholar John Peacock, was speaking at the event, replied that there is a temple in Thailand that contains a Buddha rendered as a small image of David Beckham. The symmetry is perfect. And it raises a vital question for western Buddhism. Western Buddhism presents itself as a remedy against the stresses of modern life though, as Slavoj Žižek has noted, it actually functions as a perfect supplement to modern life. It allows adherents to decouple from the stress, whilst leaving the causes of the stress intact: consumptive forces continue unhindered along their creatively destructive path. In short, Buddhism is the new opium of the people. Batchelor and Peacock might agree that this is a serious charge and grave risk. And their efforts can be interpreted as precisely to resist it. Their analysis is different. Western Buddhism is undergoing its Protestant reformation, Batchelor observed. It is about two centuries behind western Christianity in terms of its critical engagement with its canonical texts. The quest for the historical Buddha – an exercise that parallels the 19th-century quest for the historical Jesus – is only just under way. An essentially medieval Buddhism has been catapulted into modernity. It's hardly surprising that it will take two, perhaps three centuries for an authentically western form to emerge – by which is meant, in part, one that resists, not supplements, consumerism. For if Buddhism is to live in the modern world, it must be treated as a living tradition, not a preformed import. As the reformation leaders of the 16th century knew, this is a profoundly unsettling project – though it is also compelling for its promise is new life. |

| Column |

Rob Bell's Intervention in the Often Ugly World of American EvangelicalismIn its treatment of hell, the pastor's book holds two Christian truths in tension: human freedom and God's infinite love.  The question: Who is in hell? I met Rob Bell at Greenbelt, a couple of years back, because we happened to be staying in the same hotel. Though at first, I didn't know who he was. Rather, I saw him coming. He was dressed head-to-foot in black and was accompanied by three other chaps, similarly clad, carrying those impressive silver cases that speak of expensive, hi-tech gear. Then, later, I saw the long queues for his event; they were heavily oversubscribed. I made the link with the inclusive megachurch American pastor who was topping the bill. He draws congregations numbered in the tens of thousands. And now his new book, Love Wins, has achieved the ultimate accolade. A clever marketing campaign led to a top 10 Twitter trend at the end of February. Evangelicals, even liberal ones, believe the Word changes everything, and so they take words very seriously. They are entirely at home in the wordy, online age. The row on Twitter is to do with the content of the book, or at least what a number of conservative megachurch detractors assumed to be the content. It's to do with universalism – the long debate in Christianity about whether everyone is eventually saved by Jesus, or whether only an elect make it through the pearly gates. Bell's opponents assume that he is peddling the message that when the great separation comes, between the sheep and the goats, there won't be any going into the pen marked "damnation". From this side of the pond, it all feels very American, one of those things that makes you realise that the US is a foreign country after all. I'm sure that some British evangelicals debate the extent of the saviour's favour too, only they are also inheritors of the Elizabethan attitude about being wary of making windows into other people's souls. "Turn or burn!" works in South Carolina, not the home counties. (Then again, I was recently in a debate with someone who claimed to know Jesus better than his wife. I wondered whether his wife knew.) |

| Column |

Ultra-Darwinists and the pious geneRichard Dawkins won't like it, but he and creationists are singing from similar hymn sheets, according to a new book.  Here are three questions of the kind evolutionary theorists love. First, why do most mammals walk on four legs? Second, how come some single-celled protists have genomes much larger than humans? Third, why have camera eyes evolved independently in vertebrates and octopuses? They're important questions as they challenge certain versions of Darwinism that are dominant today in popular discourse. They are posed, alongside many others, in a rich mix of high theory and low knockabout in a new book by Conor Cunningham, Darwin's pious idea: How the ultra-Darwinists and creationists both get it wrong. Ultra-Darwinism is the kind associated with the new atheism, the selfish gene and what Daniel Dennett calls evolution's "universal acid". Cunningham has form when it comes to critiquing its flaws. You may have seen his TV documentary, Did Darwin Kill God? In the book, he has not one hour but several hundred pages to persuade us that a new consensus is on the way in evolutionary circles and, moreover, it's remarkably amenable to Christian theology. Consider, then, the questions. First, why do most mammals walk on four legs? It may be because four is an optimal adaptation for walking on land. Or it may be because the number four originates with the four fish fins that predate mammal legs. The difference is subtle but much hangs on it. If the number four is an optimal adaptation – not merely a byproduct of fins – then it exemplifies the power of natural selection to explain all sorts of traits. Only, consider a millipede. It would presumably think there's nothing optimal about four at all. I'd blame the fish, it might muse. And we might remember the millipede's contribution because, if it's hard to say whether features of organisms are adaptations or not, that causes all sorts of problems for the universal acid of ultra-Darwinism. Strongly adaptationist explanations are common in ultra-Darwinism and the work of the acid. But as Cunningham repeatedly – actually, obsessively – points out, when they are rehearsed as gospel, they exact a terrible price. They describe such humanly invaluable features as mind, ethics and free will as delusions – akin to what Nietzsche called "true lies". The resulting nihilism is one of Cunningham's prime objections to the paradigm. |

| Column |

Uncertainty's PromiseWhether with science or religion, only by embracing doubt can we learn and grow.  We live in an age intolerant of doubt. Communicating uncertainty is well nigh impossible across fields as diverse as politics, religion and science. There's a fear of doubt abroad too. It's most palpable, at the moment, whenever there's news of economic uncertainty. Waves of nervousness ripple through financial markets and supermarkets alike. And yet, at the same time, few would deny that only the fool believes the future is certain. And who doesn't fear that most shadowy figure of our times, the fundamentalist – with their deadly, steadfast convictions? The confusion is understandable. Doubt is unsettling. It's not for nothing that old maps inscribed terra incognita with the words "here be dragons". Further, the tremendous success of science, and the transformation of our lives by technology, screens us from many of the troubling uncertainties that our ancestors must have been so practised in handling. But are we losing what might be called the art of doubt too? For, in truth, without doubt there is no exploration, no creativity, no deepening of our humanity – which is why the individual who claims to know something beyond all doubt is a person to shun, not emulate. Stick to what you know and you'll find some security, but you'll also find yourself stuck in a rut. Learn to welcome the unknown, to embrace its thrill, and new worlds might open up before you. My old physics tutor, Carlos Frenk, is an excellent case in point. He is one of the world's leading researchers on dark matter – as is advertised by a large poster that hangs outside his office. It is inscribed with five bold words: "Dark Matter – Does It Exist?" To put it another way, Professor Frenk has forged a career out of navigating the terra incognita of the cosmos. He believes there is dark matter. It makes sense of the way visible matter in the universe hangs together. But there are no guarantees. Moreover, that's a fact that his peers ache to exploit. They seek to falsify his thesis, a negative process by which they hope to prove him wrong. That's what you have to live with when your expertise is on what's uncertain. And yet, Professor Frenk remains persistently sanguine. Falsity is the only certainty in science, he tells me. Science is organised doubt. It's only when scientists can no longer say no to a thesis that it stands. |

| Column |

The Return of Virtue EthicsWhat is the good life? How can we know?  The Enlightenment was a revolution in the way we think about morality. Two ethical models, in particular, have come to dominate ever since. One can be traced back to Immanuel Kant, and is based upon the notion of duty (and hence is called deontological, from the Greek deon, meaning duty.) The second is hedonist and can be traced back to Jeremy Bentham, and his principle of utility: an action can be called good if it increases pleasure or decreases pain. Put them together and you have the liberal approach to asking what’s the right thing to do. It’s liberal not in the sense of being pro-gay or pro-abortion. Rather, it’s liberal in the deeper sense of focusing on the individual and the choices an individual makes. It's ethics conceived of in terms of rights and responsibilities, or in terms of what makes you happy or sad. The philosopher John Stuart Mill summed it up when he wrote: "Neither one person, nor any number of persons is warranted in saying to another human creature of ripe years, that he shall not do with his life for his own benefit what he chooses to do with it." You can understand why Mill wrote what he did. He lived in a period of history in which many people were not free to do as they chose. They were ruled by monarchs and chastised by prelates. The result was the subjugation of women and the owning of slaves. But we don’t live in such a world now. Most enjoy a degree of freedom that would have been unimaginable for most of human history, in the West at least. As a result, the liberal approaches to ethics are increasingly being questioned. Can they tell us what this freedom is for? Is it for more than just more consumption, more accumulation? What is the good life? The problem is that we’ve lost touch with the bigger picture: what is it that makes life good for us humans? The Enlightenment left us with few resources for thinking about that larger question, because it was so focused on winning individuals their freedom. The philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe described our dilemma this way. Our talk of having "moral duties," or our description of actions as "morally right," has become vacuous because we are now free of the law-giving God who fixes those duties and obligations. And Anscombe, as a Catholic, was a firm believer in God — only not a law-giving God but a loving one. In any case, now that we are relatively free, we need to ask again what life is for. There is another ethical tradition that can help. It’s known as virtue ethics. Virtue ethics begins by asking what it is to be human, and proceeds by asking what virtues — or characteristics, habits and skills — we need in order to become all that we might be as humans. It’s much associated with the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, who discussed the meaning of friendship as a way to illustrate his approach to ethics. Science tells us we are social animals, Aristotle observed. But in order to live well as social animals, we also need a vision of what our sociality can be. He had a word for that vision: friendship. The good friend is someone who knows themselves, who is honest and courageous, who has time for others, who is engaged not only in their self-interest but has a concern for others. These are some of the virtues we should nurture in order to be fulfilled as friends. |

| Column |

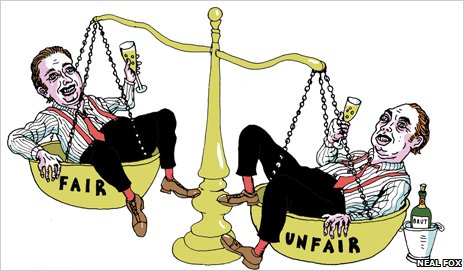

Is It Fair to Pay Bankers Big Bonuses?It's bonus season for bankers, including at banks bailed out by taxpayers. Is this just? Great thinkers like Aristotle have mulled such questions for centuries.  Is it fair and just to pay bankers big bonuses? You can seek an answer in three different ways, according to the three traditions of moral philosophy that dominate in our times, which are also explored in BBC Four's Justice: A Citizen's Guide to the 21st Century. The first answer can be summed up in a word: happiness. It's associated with the British philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who argued that if you want to know the right thing to do, ask yourself what will increase the happiness of most people, and decrease pain. Is it the size of the bonuses paid to bankers that so riles the public? The utilitarian could stress that growth, wealth and GDP contribute much to the happiness of all. These depend upon a functioning banking system. And banks, in turn, need investment bankers to turn a profit. If those bankers are best incentivised by the promise of large bonuses, then so be it. Indirectly, that makes everyone happier. The utilitarian would also consider the amount of outrage and unhappiness that large bonuses generate in the population at large. There may come a point when the happiness generated by profitable banks outweighs the unhappiness of protests at the bonuses. But then again, banks are so fundamental to our economy, and the economy is so fundamental to our happiness, that it seems unlikely this tipping point will be reached - as indeed the British government seems to have concluded. The second tradition might come to a broadly similar view, but for different reasons. It too can be summed up in a word - dignity - and is associated with the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. |

| Column |

How to Meditate: An Introduction'Mindfulness meditation' – getting to know the here and now – could be the key to a calmer, happier, healthier you.  Rates of depression and anxiety are rising in the modern world. Andrew Oswald, a professor at Warwick University who studies wellbeing, recently told me that mental health indicators nearly always point down. "Things are not going completely well in western society," he said. Proposed remedies are numerous. And one that is garnering growing attention is meditation, and mindfulness meditation in particular. The aim is simple: to pay attention – be "mindful". Typically, a teacher will ask you to sit upright, in an alert position. Then, they will encourage you to focus on something straightforward, like the in- and out-flow of breath. The aim is to nurture a curiosity about these sensations – not to explain them, but to know them. There are other techniques as well. Walking meditation is one, when you pay attention to the soles of your feet. That too carries a symbolic resonance: if breath is to do with life, feet are a focus for being grounded in reality. It's a way of concentrating on the here and now, thereby becoming more aware of how the here and now is affecting you. It doesn't aim directly at the dispersal of stresses and strains. In fact, it is very hard to develop the concentration necessary to follow your breath, even for a few seconds. What you see is your mind racing from this memory to that moment. But that's the trick: to observe, and to learn to change the way you relate to the inner maelstrom. Therein lies the route to better mental health. Mindfulness, then, is not about ecstatic states, as if the marks of success are oceanic experiences or yogic flying. It's mostly pretty humdrum. Moreover, it is not a fast track to blissful happiness. It can, in fact, be quite unsettling, as works with painful experiences, to understand them better and thereby get to the root of problems. Research into the benefits of mindfulness seems to support its claims. People prone to depression, say, are less likely to have depressive episodes if they practice meditation. Stress goes down. But it's more like going on a journey than taking a pill. Though meditation techniques can be learned quickly, it's no instant remedy and requires discipline. That said, many who attend lessons or go on retreats find immediate benefits – which is not so surprising, given that in a world of no stillness, even a little calm goes a long way. |

| Column |

How a Marxist Might See the CreedMy take on Terry Eagleton's interpretation of Christianity unites it with Marxism in a rejection of progress.  For the latest event in the Uncertain Minds series, I talked with the Marxist critic Terry Eagleton, author of Reason, Faith, and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate. We were sitting beneath the stone arches of the Wren suite, in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral. And as we conversed, I had a very odd experience. It was as if I could hear him reciting a Christian creed – sotto voce – adding in his distinctive gloss on several of the key phrases. Here's something close to what I imagined he said. I believe in God. Obviously, if I were a Christian, I wouldn't believe in God in the way that an alarming proportion of Americans believe in alien abduction. After all, Satan believes in God in that sense. He knows God exists. But he doesn't trust in God and isn't committed to God's ways. Quite the opposite. Alain Badiou, probably the greatest philosopher alive today, writes about having a commitment to a revelatory event. That must be more like what a Christian believes. Creator of heaven and earth. This, of course, has absolutely nothing to do with the big bang. Those who are tempted to think of it as a reference to divine pyrotechnics on a cosmic scale should read a little Wittgenstein. Creator-talk is theology, and that's a different language game from science. Rather, to call God the creator means that you believe the universe has a purpose. As to how it was done – physics has a few ideas. As to what that purpose might be – well, we perhaps glean something from the next line. I believe in Jesus Christ. Jesus is the locus for a remarkable set of stories. They are remarkable because they remember a life that clung to faith even when the subject of that life was hanging half dead from a tree. As my sometime fellow papist Marxist, Herbert McCabe, once put it: if you don't love you die, if you do love they kill you. In this tragic world of ours, that seems to me to be quite true. And remember, tragedy is not the same as pessimism because pessimism gives up hope, which is precisely what Jesus didn't do. Though he had more reason than most to do so. |

| Column |

William James, Part 8: Agnosticism and Pragmatic PluralismWilliam James wanted a philosophy that rested on experience, not logic, because life exceeds logic.  "The most important thing about a man," wrote Chesterton, "is his philosophy." William James agreed. He was fond of quoting the saying. Our philosophy, or "over-belief", shapes our "habits of action," which is to say our ethos – who we are becoming. Pragmatism, the philosophy of "what works," is taken to be James' philosophy. And yet, his pragmatism is different from that of his confrères. Pragmatism is often associated with deflationary accounts of truth. Truth, with a capital T, is a pipe dream, it implies. No fact, rule or idea is ever certain – nor is even the possibility of facts, rules and ideas. Philosophy and science can make progress, but only in relation to current experience. "Truth is the opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate", wrote one pragmatist philosopher, John Dewey. Or as Richard Rorty pithily averred: "Time will tell, but epistemology won't." When it comes to religion, such pragmatism implies that theologians are more like poets than metaphysicians. They are aestheticians – conjuring meaning with their descriptive powers, as opposed to capturing Truth in their formularies. It's called ironic pragmatism. "There is an all" is inverted to "that's all there is." Such a stance requires the philosopher, or scientist, to be committed to finding the truth as it if existed, though it probably doesn't. It's truth as a "regulative ideal," to use another phrase. So, if James is a pragmatist, what of his religious quest? Is he condemned to perpetual agnosticism – longing for more and never finding it? It's a big debate amongst Jamesian scholars. But I think his ethos, his philosophy, can be summarised like this. |

| Column |

William James, Part 7: Agnosticism and the Will to BelieveJames observes that the idea you can will belief in God is 'simply silly,' as the nature of real assent consists of many strands.  There is an agnostic sensibility that runs through William James – in this sense: he knows that any claim of knowledge based on religious experience could, in principle, be mistaken. But it may be true, too. He's convinced that the fruits of "spiritual emotions" are morally helpful for humankind, notwithstanding that some fruits become rotten. He's probed mystical experiences – that sense of oneness with the Absolute – to see whether they can decide the case. They can for the individual concerned, he concludes. But, as he observes at the start of lecture 18, mysticism is "too private (and also too various) in its utterances to be able to claim a universal authority". So, in the final sections of the Varieties, the question of whether religious experiences point to objective truth becomes pressing. "Can philosophy stamp a warrant of veracity upon the religious man's sense of the divine?" he asks. Well, first, you've got to ask what religious philosophy is. It seems obvious to him that it is secondary to religious experience because it is passion, not reason, that fundamentally drives such areas of human inquiry (and quite possibly all areas of human inquiry). Philosophy is necessary, but not sufficient. In fact, he loathes what he elsewhere calls "vicious intellectualism" – the preference for concepts over reality. It's cultivated by the fantasy of an objective science – and is insidious because it turns you into a spectator of, not a participant in, life. It encourages speculation for speculation's sake, and like the bankers who engage in the financial equivalent, the result is ideological bubbles. They rise high in the intellectual firmament before they burst and crash back to earth. In the sphere of religion, James detects such "vicious intellectualism" most clearly in the attempts to demonstrate the existence of God as an a priori fact. The ontological and cosmological proofs are for those who wish to cleanse themselves of the "muddiness and accidentality" of the world. Interestingly, he describes the recently beatified John Henry Newman as one such "vexed spirit". He charges the cardinal with a "disdain for sentiment", though I'm not sure that's fair. In fact, Newman seems quite close to James in certain respects, particularly in relation to what Newman called the "grammar of assent". |

| Column |

William James, Part 6: Mystical StatesJames's discussion of mysticism is not unproblematic, but there is significant value in the way he frames the subject.  Mysticism is a crucial aspect of the study of religion. "One may say truly, I think, that personal religious experience has its roots and centre in mystical states of consciousness," William James writes in The Varieties. That said, it's important to be clear about what he means by phrases like "states of consciousness". Our view is coloured by a psychologising tendency that's grown since James. It can be associated, in particular, with Abraham Maslow's notion of "peak experiences" – the ecstatic states that satisfy the human need for self-actualisation. This exaltation of feelings of interconnectedness is questionable on two counts. First, Maslow's analysis is scientifically dubious. As Jeremy Carrette and Richard King put it: "Sampling disillusioned college graduates, Maslow would ask his interviewees about their ecstatic and rapturous moments in life." No offence to students, but they probably do not provide the best samples of mystics. A second critique of Maslow's work is found in the writings of the great spiritual practitioners themselves. The author of The Cloud of Unknowing, for one, explicitly argues that, whatever the mystical might be, it is hidden from experience. Or, as any decent meditation teacher will tell you, clinging to oceanic experiences will hinder your progress quite as much as clinging to anything else. This is not to say that mystical experience has nothing to do with feelings, James continues. Rather, it is a state both of feeling and of knowledge, of wonder and intellectual engagement. The two faculties must be deployed when weighing any insight. "What comes," James explains, "must be sifted and tested, and run the gauntlet of confrontation with the total context of experience." Mystical states can, therefore, be assessed for their truth value. But how? Not, James explains, in the way advocated by the "medical materialists" – those for whom mysticism signifies nothing but "suggested and imitated hypnoid states, on an intellectual basis of superstition, and a corporeal one of degeneration and hysteria". |

| Column |

William James, Part 5: SaintlinessReligious experiences, and their saintly effects, are morally helpful, not damaging or repugnant.  One of Friedrich Nietzsche's fiercest attacks on Christianity pitches against the exalted virtues of saintliness. He believed the worship of the crucified encouraged a vile, slave mentality in its adherents. It's partly a result of being required to submit to a superior deity; partly a result of the moral demand to serve others. Christianity, he concluded, is dehumanising. He has a point. Consider what might happen should you take pity on someone, as the Christian ethic of love requires. This virtue, Nietzsche insists, is really the desire to take possession. Thus, when we see someone who is suffering, and act on a feeling of compassion, we make ourselves their benefactor. We set ourselves over them, and leave them in need of us. We might not only congratulation ourselves for our sympathy, but could well prefer attending to the suffering of others to facing our own distress – the phenomenon of the wounded healer who helps others because they cannot help themselves. Far better, Nietzsche thought, that individuals pursue their own way through suffering – though not in isolation. Rather, do so together, and so learn to rejoice, in spite of it all. That way suffering is not spread, and joy might be increased. This was a conclusion that worried William James, and in the The Varieties of Religious Experience he devotes five lectures to challenging it. It troubled him because he was keen to show that religious experiences, and their saintly effects, are morally helpful, not damaging or repugnant. "The highest flights of charity, devotion, trust, patience, bravery to which the wings of human nature have spread themselves have been flown for religious ideals," he avers. He sets out on a lengthy analysis of cases to prove his point. |

| Column |

William James, Part 4: The Psychology of ConversionReligious conversion, be it sudden or slow, causes a revolution in the personality.  The case of Stephen H Bradley, reported by William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience, is arresting. At the age of 14, he had a vision of Jesus. It lasted only a second. Christ was in the young man's room, "with arms extended, appearing to say to me, Come." From that day on, Bradley called himself a Christian. Then, when he was in his mid-20s, he attended a revivalist meeting. It left him cold, and that troubled him, as he regarded himself as religious. Then, later that evening, he was gripped by an even more profound experience than the first. His heart beat fast. He became elated, while also feeling worthless. He experienced a stream of air passing through him. The next morning, he believed he could see "a little heaven upon earth". He visited his neighbours, "to converse with [them] on religion, which I could not have been hired to have done before". He concludes: "I now defy all the deists and atheists in the world to shake my faith in Christ." Bradley had undergone a religious conversion and, as is his wont, James considers a range of similar cases in the Varieties. They can show a sense of regeneration, or a reception of grace, or a gift of assurance. What distinguishes religious conversion from more humdrum experiences of change is depth. Human beings quite normally undergo alterations of character: we are one person at home, another at work, another again when we awake at four in the morning. But religious conversion, be it sudden or slow, results in a transformation that is stable and that causes a revolution in those other parts of our personality. Hence, before his conversion, Augustine prayed to be chaste but "not yet", which is only to underline that, with his conversion, what was previously impossibility became actual. It's that personal drama that leads the convert to ascribe the change to God. But, strictly as a psychologist, what sense can be made of it? James resorts to what he believes to have been the greatest discovery of modern psychology, namely that subconscious forces play a defining role in the life of an individual, even when they have no conscious awareness of them. |

| Column |

William James, Part 3: On Original SinAre humans born happy, able to create their own well-being, or do we need to be born again to overcome a 'sick soul'?  Original sin is a religious doctrine that divides perhaps more than any other. For some, it only makes sense – maybe not the part about the apple and the garden, but the general idea that humankind is flawed: we do what we wouldn't do, and don't do what we would do, as St Paul put it. For others, though, original sin is vile and offensive. It feeds the fear of hell, a hopelessness about progress, and leaves us pathetically dependent on God. Each side has a radically different view of what it is to be human, and William James understands exactly what's a stake. It follows from one of the most interesting distinctions he draws in the Varieties. There are some, he explains, who take the happiness that religion gives them to be the amplest demonstration of its truth. Then, there are others who take the remedy that religion offers for the ills of the world to be the amplest reason for its necessity. James adopts the terms "once-born" to describe the happy sort, and "twice-born" for the more pessimistic. The link between the phrase "once-born" and the positive temperament is that these individuals believe that seeing God – or finding fulfilment, or simply living well – is no more or less difficult than seeing the sun. On some days it will be cloudy. But the skies eventually clear. The cosmos is fundamentally good, they affirm. Human individuals are, basically, kind. Your first birth, as a baby, is the only birth that's required to see the world aright. This temperament is, James explains, "organically weighted on the side of cheer and fatally forbidden to linger, as those of opposite temperament linger, over the darker aspects of the universe." James's favourite example of the once-born is Walt Whitman. "He has infected [his readers] with his own love of comrades, with his own gladness that he and they exist." Alongside Whitman, there are some Christians who fall into this category. (Not all take original sin that seriously.) They are of a liberal sort, believing that the significance of Jesus is found in his moral teaching, which if followed would lead to a more perfect world. Popular science-writing has contributed to the increase of this kind of belief too, as it conveys the conviction that human beings can understand themselves and, thereby, fix themselves. Eastern ideas imported into the west offer something similar. Hence, meditation techniques, such as mindfulness, are sold as being scientific and empowering. |

| Review |

The Age of EmpathyNature's Lessons for a Kinder Society  This is a confused book because it is trying to do several things at once. It is partly a study of animal empathy, the area of work for which Frans de Waal is well known. But de Waal is also fighting other battles, notably over whether there are sharp dividing lines between humans and other animals. And here he is much less sure of his ground. The difficulty is that, in stressing the co-operative side of animal behaviour, de Waal sidelines an important trait on which human difference turns: cognition. It was not a mistake Charles Darwin made when, in The Descent of Man (1871), he noted that although animals have "well-marked social instincts", it is "intellectual powers", such as humans have, that lead to the acquisition of the moral sense of right and wrong. The book fails when it comes to the third goal de Waal sets himself: to champion empathy as a solution to social, even political, problems. He resists the notion that empathy is innately morally ambivalent, overlooking how sadistic behaviour, for example, arises from empathising with a victim, too. Occasionally he admits that empathy is psychologically complex, but rather than exploring this complexity, he quickly returns to reciting evidence more congenial to his thesis. He briefly offers a more sophisticated account of emotional connectivity, but again ignores its ramifications. This is a hierarchical model, and begins with the inchoate feelings that arise from witnessing another's exhilaration or distress. Next, there is "self-protective altruism" - doing something that benefits another person, though only in order to protect yourself from unpleasant emotional contagion. Then there is "perspective-taking", which is stepping into the shoes of another. But it is not unless the individual has a further capacity, sympathy, that he or she knows how to improve the lot of others. What distinguishes sympathy is that it allows both emotion and understanding (Darwin's "intellectual powers") to be brought to bear on the situation at hand. Such faculties, however, are not the basis for moral behaviour that de Waal seeks. Indeed, he "shudder[s] at the thought that the humaneness of our societies would depend on the whims of politics, culture, or religion". One may shudder with him, but one might shudder more if our ability to act humanely rested solely on the morally flawed capacity of empathy. |

| Column |

William James, Part 2: The Scientific Study of ReligionJames demonstrates how identifying the physiological bases for religious experience explains very little.  The Scotsman of May 1901 records how William James began the lectures that became The Varieties of Religious Experience, "in the English class-room of [Edinburgh] University, where a crowded audience assembled". He was the kind of communicator who attracted more and more auditors as a course proceeded. When, in 1908, he gave the Hibbert lectures in Oxford, the venue had to be changed from a modest library to the vast rooms of the Examination Schools building. "It is with no small amount of trepidation that I take my place behind this desk," he opened, "and face this learned audience." The reasons for his strikingly humble tone were several. American universities had only recently started to award higher degrees, so thinkers of James' generation travelled to Europe to research. James himself had no such academic qualification. That said, it quickly became clear that he had all the boldness of the brilliant amateur. His lectures would examine the perennial human phenomenon of religious experience, from a psychological not ecclesiastical or theological perspective. He would confine his evidence to records produced by articulate, often remarkable individuals. He would be clear to draw a difference between the nature of religious experiences, and the value of religious truths to humankind. It is easy, he notes, to slip from explaining the former to passing judgment on the latter, though the move is fallacious. James explains why in the first lecture. He was a keen Darwinian, and so he asks us to consider the kind of evolutionary explanation for religion that argues it has some survival advantage, or that draws a connection between, say, religious emotions and sexual life. It's a reasonable hypothesis. Everything has causes. What's a mistake, though, is to think these aetiologies explain away the authority the experiences carry. James calls that error "medical materialism". This "too simple-minded system … finishes up Saint Paul by calling his vision on the road to Damascus a discharging lesion of the occipital cortex, he being an epileptic. It snuffs out Saint Teresa as an hysteric." Paul may well have had an epileptic episode. But that's only to say that there is a biological component to all human experience. "Scientific theories are organically conditioned just as much as religious emotions are; and if we only knew the facts intimately enough, we should doubtless see "the liver" determining the dicta of the sturdy atheist as decisively as it does those of the Methodist under conviction anxious about his soul." |

| Column |