Shankar Vedantam

Shankar Vedantam is a national correspondent writing about science and human behavior for the Washington Post. He previously worked at the Philadelphia Inquirer, Knight-Ridder's Washington Bureau, and New York Newsday. Vedantam has a master's degree in journalism from Stanford University and an undergraduate degree in electronics engineering. He is interested in the history of conflict over the theory of evolution, the changes over time of religious theories concerning the creation of the universe, and the effects of religious faith on health. He has written about the interplay between neuroscience and spirituality, an area he would like to explore further.

| Broadcast |

The Key To Disaster Survival? Friends And Neighbors When Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005, one victim was political scientist Daniel Aldrich. He had just moved to New Orleans. Late one August night, there was a knock on the door. "It was a neighbor who knew that we had no idea of the realities of the Gulf Coast life," said Aldrich, who is now a political scientist at Purdue University in Indiana. He "knocked on our door very late at night, around midnight on Saturday night, and said, 'Look, you've got small kids — you should really leave.' " The knock on the door was to prove prophetic. It changed the course of Aldrich's research and, in turn, is changing the way many experts now think about disaster preparedness. Officials in New Orleans that Saturday night had not yet ordered an evacuation, but Aldrich trusted the neighbor who knocked on his door. He bundled his family into a car and drove to Houston. "Without that information we never would've left," Aldrich said. I think we would've been trapped." In fact, by the time people were told to leave, it was too late and thousands of people got stuck. Social Connections And Survival: Neighbors MatterBecause of his own experience in Katrina, Aldrich started thinking about how neighbors help one another during disasters. He decided to visit disaster sites around the world, looking for data. Aldrich's findings show that ambulances and firetrucks and government aid are not the principal ways most people survive during — and recover after — a disaster. His data suggest that while official help is useful — in clearing the water and getting the power back on in a place such as New Orleans after Katrina, for example — government interventions cannot bring neighborhoods back, and most emergency responders take far too long to get to the scene of a disaster to save many lives. Rather, it is the personal ties among members of a community that determine survival during a disaster, and recovery in its aftermath. |

| Broadcast |

What Science Tells about Power and Infidelity On tonight's All Things Considered, NPR's science correspondent Shankar Vedantam takes on a subject we've been covering quite a bit lately: Powerful people caught up in scandals. Anthony Weiner, John Edwards, Arnold Schwarzenegger — men behaving badly, right? It may be more complex than that. Research shows power causes men and women to take risks and imagine themselves as more attractive. New survey research shows that, given power, women are as likely as men to stray. MELISSA BLOCK, host: And Mark Sanford is one of the cascade of politicians linked to sex scandals. If you print out the Wikipedia page for federal political sex scandals, in the U.S. alone, it runs to six single-spaced pages. And recently, it's gotten two names longer, both of them congressman from New York. NPR science correspondent Shankar Vedantam explains why so many powerful people get caught up in sexual indiscretions. SHANKAR VEDANTAM: The confessions we've heard in recent years from powerful men and sex scandals all sounded alike. Listen to Congressman Anthony Weiner, Senator John Ensign, governors Eliot Spitzer and Mark Sanford, and Senator David Vitter. |

| Column |

Walking Santa, Talking ChristWhy do Americans claim to be more religious than they are?  Two in five Americans say they regularly attend religious services. Upward of 90 percent of all Americans believe in God, pollsters report, and more than 70 percent have absolutely no doubt that God exists. The patron saint of Christmas, Americans insist, is the emaciated hero on the Cross, not the obese fellow in the overstuffed costume. There is only one conclusion to draw from these numbers: Americans are significantly more religious than the citizens of other industrialized nations. Except they are not. Beyond the polls, social scientists have conducted more rigorous analyses of religious behavior. Rather than ask people how often they attend church, the better studies measure what people actually do. The results are surprising. Americans are hardly more religious than people living in other industrialized countries. Yet they consistently—and more or less uniquely—want others to believe they are more religious than they really are. Religion in America seems tied up with questions of identity in ways that are not the case in other industrialized countries. When you ask Americans about their religious beliefs, it's like asking them whether they are good people, or asking whether they are patriots. They'll say yes, even if they cheated on their taxes, bilked Medicare for unnecessary services, and evaded the draft. Asking people how often they attend church elicits answers about their identity—who people think they are or feel they ought to be, rather than what they actually believe and do. The better studies ascertain whether people attend church, not what they feel in their hearts. It's possible that many Americans are deeply religious but don't attend church (even as they claim they do). But if the data raise serious questions about self-reported church attendance, they ought to raise red flags about all aspects of self-reported religiosity. Besides, self-reported church attendance has been held up as proof that America has somehow resisted the secularizing trends that have swept other industrialized nations. What if those numbers are spectacularly wrong? To the data: There was an obvious clue (in hindsight) that the survey numbers were hugely inflated. Even as pundits theorized about why Americans were so much more religious than Europeans, quiet voices on the ground asked how, if so many Americans were attending services, the pews of so many churches could be deserted. "If Americans are going to church at the rate they report, the churches would be full on Sunday mornings and denominations would be growing," wrote C. Kirk Hadaway, now director of research at the Episcopal Church. (Hadaway's research has included evangelical congregations, which reported sharp growth in recent decades.) |

| Radio Broadcast |

Can We Live Without a Hidden Brain? A new interview explores what happens to people when they are deprived of their hidden brains. Much of The Hidden Brain is about the problems that unconscious factors create in our lives — from the vagaries in our moral judgment to the ways in which suicide bombers are indoctrinated. A natural conclusion from these examples is that we would be much better off without the hidden brain. This idea turns out to be impractical, and also fails to account for the many positive things the hidden brain does for us each day. In a chapter called Tracking the Hidden Brain (watch a video introduction to it here) I show what happens to a middle-aged woman in Canada who loses a part of her hidden brain — a disorder robs her of subtle mental skills that she needs to function in social settings. She not only loses the ability to relate in appropriate ways to her family and to her friends, but also develops a host of unusual behaviors that puzzle the people who know and love her best. read more… listen… [Wisconsin Public Radio Player, 51 mins] |

| Interview |

The Hidden Brain and the Telescope EffectHow we think about tragedy We know genocide is a greater tragedy than a lost dog. Or do we? Washington Post staff writer Shankar Vedantam discusses the "telescope effect" and the manner in which our brains process tragedy and empathy in a Washington Post Magazine article adapted from his book, "The Hidden Brain: How Our Unconscious Minds Elect Presidents, Control Markets, Wage Wars and Save Our Lives," to be published this week. He took questions and comments January 19. The transcript is below ____________________ Shankar Vedantam: Welcome to this online discussion about my Sunday magazine story -- Beyond Comprehension -- that was published last weekend. The story is excerpted from my new book, The Hidden Brain: How Our Unconscious Minds Elect Presidents, Control Markets, Wage Wars and Save Our Lives. The book is launched today by Random House Inc. The excerpt is drawn from the final chapter of the book, which explores twin biases in the way we think about large numbers and small numbers. I argue in the excerpt published in the magazine that errors in the way our minds process large numbers leads us to make systematic errors in moral judgment. I cite a number of experimental studies, many of which were conducted by the superb psychologist Paul Slovic, that demonstrate how unconscious biases subtly alter our perceptions about different tragedies, and cause us to feel more visceral compassion when the number of victims is small, and less visceral compassion when the number of victims is large. You can learn more about my book at www.hiddenbrain.org, follow the connections I make between unconscious bias and news events at www.twitter.com/hiddenbrain and form your own discussion group at www.facebook.com/hiddenbrain _______________________ Freising, Germany: When you write that humans respond best to a single victim, I wonder if that has to do with empathy and perhaps also the instinct that if you help an individual, you yourself as an individual may someday be helped as well. |

| Column |

Shades of Prejudice LAST week, the Senate majority leader, Harry Reid, found himself in trouble for once suggesting that Barack Obama had a political edge over other African-American candidates because he was "light-skinned" and had "no Negro dialect, unless he wanted to have one." Mr. Reid was not expressing sadness but a gleeful opportunism that Americans were still judging one another by the color of their skin, rather than — as the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whose legacy we commemorated on Monday, dreamed — by the content of their character. The Senate leader’s choice of words was flawed, but positing that black candidates who look "less black" have a leg up is hardly more controversial than saying wealthy people have an advantage in elections. Dozens of research studies have shown that skin tone and other racial features play powerful roles in who gets ahead and who does not. These factors regularly determine who gets hired, who gets convicted and who gets elected. Consider: Lighter-skinned Latinos in the United States make $5,000 more on average than darker-skinned Latinos. The education test-score gap between light-skinned and dark-skinned African-Americans is nearly as large as the gap between whites and blacks. The Harvard neuroscientist Allen Counter has found that in Arizona, California and Texas, hundreds of Mexican-American women have suffered mercury poisoning as a result of the use of skin-whitening creams. In India, where I was born, a best-selling line of women’s cosmetics called Fair and Lovely has recently been supplemented by a product aimed at men called Fair and Handsome. This isn’t racism, per se: it’s colorism, an unconscious prejudice that isn’t focused on a single group like blacks so much as on blackness itself. Our brains, shaped by culture and history, create intricate caste hierarchies that privilege those who are physically and culturally whiter and punish those who are darker. |

| Article |

Beyond ComprehensionWe know that genocide and famine are greater tragedies than a lost dog. At least, we think we do.  On March 13, 2002, a fire broke out in the engine room of an oil tanker about 800 miles south of Hawaii. The fire moved so fast that the Taiwanese crew did not have time to radio for help. Eleven survivors and the captain's dog, a terrier named Hokget, retreated to the tanker's forecastle with supplies of food and water. The Insiko 1907 was supposed to be an Indonesian ship, but its owner, who lived in China, had not registered it. In terms of international law, the Insiko was stateless, a 260-foot microscopic speck on the largest ocean on Earth. Now it was adrift. Drawn by wind and currents, the Insiko got within 220 miles of Hawaii. It was spotted by a cruise ship, which diverted course and rescued the crew. But as the cruise ship pulled away, a few passengers heard the sound of barking. The captain's dog had been left behind on the tanker. A passenger who heard the barking dog called the Hawaiian Humane Society in Honolulu. The animal welfare group routinely rescued abandoned animals -- 675 the previous year -- but recovering one on a tanker in the Pacific Ocean was something new. The U.S. Coast Guard said it could not use taxpayer dollars to save the dog. The Insiko's owner wasn't planning to recover the ship. The Humane Society alerted fishing boats about the lost tanker. Media reports began appearing about Hokget. Something about a lost dog on an abandoned ship in the Pacific gripped people's imaginations. Money poured into the Humane Society to fund a rescue. One check was for $5,000. Donations eventually arrived from 39 states, the District of Columbia and four foreign countries. "It was just about a dog," Pamela Burns, president of the Hawaiian Humane Society, told me. "This was an opportunity for people to feel good about rescuing a dog. People poured out their support. A handful of people were incensed. These people said, 'You should be giving money to the homeless.'" But Burns thought the great thing about America was that people were free to give money to whatever cause they cared about, and people cared about Hokget. |

| Column |

The Rational Underpinnings of Irrational Anger"I know how unpopular it is to be seen as helping banks right now, especially when everyone is suffering in part from their bad decisions. I promise you, I get it. But I also know that in a time of crisis, we cannot afford to govern out of anger." -- President Obama, in his address to Congress last week William Neilson is mad at all the people who bought homes they could not afford and the bankers who enabled them in order to turn a fast buck. He is mad because he has always paid his mortgage on time and had the common sense not to borrow four times the value of his house. He is mad because, now that the economy is in a tailspin, the president wants honest taxpayers like him who did everything right to lend a hand to help out those who did everything wrong. Obama's blueprint to lead the country out of recession faces many hurdles, but no challenge may be as great -- or embedded as deeply in the human psyche -- as the visceral distaste many Americans feel about propping up banks and Wall Street "masters of the universe." In his address to Congress last week, Obama stressed that the point of pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into banks and other financial institutions is not to help bankers but to help ordinary people who depend on banks. If huge banks and other financial institutions collapse as Lehman Brothers did, many economists say, it could send the economy into an even deeper tailspin. |

| Column |

Mass Suffering and Why We Look the Other Way When President-elect Barack Obama, an early opponent of the Iraq war, asked Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton -- who helped to authorize the war -- to be his secretary of state, many liberals scratched their heads. When Obama asked Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates -- a Republican who has run the Iraq war for more than two years -- to stay on in his new administration, the scratching grew fierce. But no one needs to read the tea leaves on one particular aspect of Obama's foreign policy: Obama, Clinton and Vice President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr. have all called for aggressive American action against humanitarian crises and genocide. Susan E. Rice, Obama's nominee for U.N. ambassador, has said that if a Rwanda-style genocide began again, she "would come down on the side of dramatic action, going down in flames if that was required." Samantha Power, a leading proponent for an interventionist American policy in humanitarian crises, was a senior Obama adviser during the presidential campaign. "Look empirically at the kind of people who will populate the decision-making positions in the new administration and compare them with the principals" in the George W. Bush and Bill Clinton administrations, said John Prendergast, co-chairman of the Enough Project, an advocacy group that fights genocide. "What we will get, possibly for the first time in my life, is leadership from the top in these crises." Obama might want to include a scientist named Paul Slovic in his team. Slovic, a professor at the University of Oregon, has conducted experiments that provide an unusual window into why the United States has often failed to intervene in humanitarian crises -- and why it is likely to remain slow to do so in the future. Slovic's research suggests that the central reason the United States has not responded forcefully -- and quickly -- to crises ranging from the Holocaust to the Rwandan genocide, from the ethnic cleaning that occurred in the 1990s Balkan conflict to the present-day crisis in Sudan's Darfur region, is not that presidents are uncaring, or that Americans only value American lives, but that the human mind has been unintentionally designed to respond in perverse ways to large-scale suffering. In a rational world, we should care twice as much about a tragedy affecting 100 people as about one affecting 50. We ought to care 80,000 times as much when a tragedy involves 4 million lives rather than 50. But Slovic has proved in experiments that this is not how the mind works. When a tragedy claims many lives, we often care less than if a tragedy claims only a few lives. When there are many victims, we find it easier to look the other way. Virtually by definition, the central feature of humanitarian disasters and genocide is that there are a large number of victims. "The first life lost is very precious, but we don't react very much to the difference between 88 deaths and 87 deaths," Slovic said in an interview. "You don't feel worse about 88 than you do about 87." |

| Column |

In the Face of Tragedy, Moral and Consequential ReasoningFrom the World Trade Center to Mumbai  When nearly 200 people in India were killed in terrorist attacks late last month, the carnage received saturation media coverage around the globe. When nearly 600 people in Zimbabwe died in a cholera outbreak a week ago, the international response was far more muted. The Mumbai attacks have raised talk of war between India and Pakistan and triggered a flurry of diplomatic responses. Nothing remotely on the same scale has occurred over the Zimbabwe cholera outbreak, even though many more people have died as a result of the disease compared with the toll in the Mumbai rampage. Comparing tragedies is problematic, because human lives cannot be reduced to arithmetic. Yet it is unquestionably true that nations tend to focus far more time, money and attention on tragedies caused by human actions than on the tragedies that cause the greatest amount of human suffering or take the greatest toll in terms of lives. Is this because terrorism poses a greater threat to us than epidemics? Not likely. If you were to make a list of the world's top 10 killers, suicide bombers would be nowhere on the list. In recent years, a large number of psychological experiments have found that when confronted by tragedy, people fall back on certain mental rules of thumb, or heuristics, to guide their moral reasoning. When a tragedy occurs, we instantly ask who or what caused it. When we find a human hand behind the tragedy -- such as terrorists, in the case of the Mumbai attacks -- something clicks in our minds that makes the tragedy seem worse than if it had been caused by an act of nature, disease or even human apathy. "When a bad event occurs, this automatically triggers us to seek out whoever is causally responsible," said Fiery Cushman, a cognitive psychologist with Harvard University's interdisciplinary Mind, Brain and Behavior Initiative. "When we assign causal responsibility, it is like, 'Case closed, the detectives can go home.' " Tragedies, in other words, cause individuals and nations to behave a little like the detectives who populate television murder mystery shows: We spend nearly all our time on the victims of killers and rapists and very little on the victims of car accidents and smoking-related lung cancer. "We think harms of actions are much worse than harms of omission," said Jonathan Baron, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania. "We want to punish those who act and cause harm much more than those who do nothing and cause harm. We have more sympathy for the victims of acts rather than the victims of omission. If you ask how much should victims be compensated, [we feel] victims harmed through actions deserve higher compensation." The point of this research is not to play down one tragedy or inflate another. Rather, the psychologists said, studying how we reach moral conclusions can help us understand how we respond to human suffering and alert us to pitfalls in our thinking. |

| Column |

Why Fluff-Over-Substance Makes Perfect Evolutionary Sense Scandal A: A prominent politician gets caught sleeping with a campaign aide and plunges himself into an ugly paternity dispute -- all while his cancer-stricken wife is fighting for her life. Scandal B: A prominent politician's signature health-care plan turns out to have been put together badly, and he is forced to confess that the plan will cost taxpayers billions more than expected. It's a no-brainer which scandal is likely to catch -- and keep -- our attention. The interesting question as the presidential election heads into the homestretch is why we care more about some stories that do not affect us directly, even as we tune out other stories that do. It isn't just about sex. John F. Kerry was damaged by accusations about his military service in Vietnam; George W. Bush fended off endless accusations that he dodged military service using family connections -- events that allegedly occurred more than three decades earlier. Rumor mills on the Internet today insinuate that John McCain once admitted to being a war criminal (he did not) and that Barack Obama is a Muslim (he is not). The question is not which scandals are true but why certain story lines hook our interest. Why are we more likely to discuss a gossipy rumor at a party than a policy error that can actually make a material difference to our own lives? One explanation is that cultural mores attune us to certain stories -- we live in an era where gossipy scandals rule. To test this, psychologist Hank Davis at the University of Guelph in Ontario examined hundreds of sensational stories on the front pages of newspapers in eight countries over a 300-year period, from 1701 to 2001. Remarkably, he concluded that the themes of sensational news were identical not only across the centuries but also in diverse geographic locales -- from the United States to Bangladesh, from Canada to Mauritius. The stories that editors put on the front pages of newspapers -- presumably stories that interested readers -- included headlines such as "Crocodiles Tear Apart Thai Suicide Woman." The stories were sometimes about important things and sometimes not, but they nearly always involved the kind of themes that people who are part of small groups like to know about one another: lying and cheating, altruism and heroism, loyalty and disloyalty. |

| Column |

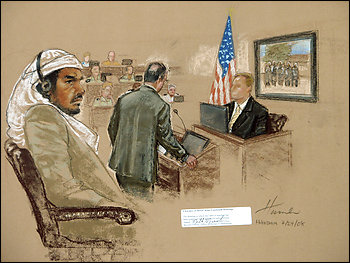

How Terrorist Organizations Work Like ClubsWhy members sacrifice themselves  ays before the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, Osama bin Laden left his compound in Kandahar in Afghanistan and headed into the mountains. His driver, Salim Ahmed Hamdan, traveled with him. As U.S. and Northern Alliance forces stood poised to capture Kandahar a few months later, bin Laden told Hamdan to evacuate his family. Hamdan's wife was eight months pregnant at the time, and Hamdan drove her and his infant daughter to the Pakistani border. It was on his way back that Hamdan was captured by Northern Alliance warlords, said Jonathan Mahler, an author who has pieced together the events in his upcoming book, "The Challenge: Hamdan v. Rumsfeld and the Fight Over Presidential Power." Hamdan's captors found two surface-to-air missiles in the trunk of his car. They turned him over to the Americans and pocketed a bounty of $5,000. Hamdan recently became the first detainee at Guantanamo Bay to face trial. Government and defense lawyers are arguing about Hamdan's significance in al-Qaeda and the extent of his knowledge of the group's activities, but it is the facts the lawyers agree on that raise an interesting question for anyone who studies terrorist groups. Hamdan joined bin Laden after his plan to go to join a jihad in Tajikistan hit a snag. For years, he ferried al-Qaeda's leader to camps and news conferences and was often bored, according to the testimony of his interrogators. Mahler, who interviewed Hamdan's family and attorneys, his FBI interrogators, and the man who recruited Hamdan for jihad, said bin Laden's driver was not particularly religious -- for a poor man from Yemen, jihad was a career move as much as a religious quest. |

| Article |

Financial Hardship and the Happiness ParadoxThe United States is awash in gloom. Overwhelming majorities of Americans say they are dissatisfied with the country's economic direction, and the intensity of unhappiness is greater than it has been in 15 years, according to a recent Washington Post-ABC News poll. The answer, pundits, politicians and policy wonks agree, is to find a way to quickly return to economic growth. The unstated assumption is that growth will lift the gloom and, in the long run, make America happier. If that's true, then it ought to follow that America should be much happier today than it was a generation ago -- it is much wealthier. The question of whether the country is happier today than it was in, say, 1970 turns out to have a surprisingly good empirical answer. For nearly four decades, researchers have regularly asked a large sample of Americans a simple question: "Taken all together, how would you say things are these days -- would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy or not too happy?" The results are sobering. Even before the current economic downturn, the United States, on average, was less happy than it was in 1970, even though it is vastly richer. Economist Richard A. Easterlin at the University of Southern California was among the first to notice the paradoxical disconnect between a nation's economic growth and the growth of its happiness. The "Easterlin Paradox" was once thought to be limited to rich, |

| Column |

Petroleum Feeds PatriarchyClimate change. Pollution. Financial expense. Our gas-guzzling ways have long been associated with a variety of problems, but disturbing evidence now points to a new dimension of our love affair with petroleum: Oil consumption and high oil prices hurt the political, social and economic development of millions of women in oil-producing nations. You read that right. The more gas you pump and the higher oil prices get, the more likely you are to harm women's empowerment. The surprising finding, based on more than four decades of data from 169 countries, provides a novel explanation of why women in Middle Eastern countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates still do not have the right to vote. Oil wealth, not Islam, is the primary reason that these nations have regressive gender policies, said political scientist Michael Ross at the University of California at Los Angeles. As implausible as the connection between oil wealth and gender rights might seem, Ross's work is based on a widely observed pattern: As oil prices soar to more than $100 a barrel, oil-producing countries get rich atop a tidal wave of foreign currency. The tsunami of cash strengthens their currencies and makes it cheaper for them to buy everything from textiles to cars from other nations, instead of manufacturing such goods at home. As a result, the economies of oil-producing nations invariably have stunted manufacturing sectors while boosting construction and services sectors. This pattern is now so familiar that it has a name -- the "Dutch Disease" -- following the reshaping of the Dutch economy |

| Article |

Is Great Happiness Too Much of a Good Thing? Ten years ago, Harry Lewenstein was riding a bike down a hill in southern Portugal when he hit a bump without warning. The 70-year-old retired electronics executive was going fast, and the shock propelled him clear over the handlebars. When his wife and friends rushed up, they found him flat on his back. Sensing that he might have spinal cord damage, one friend poked his foot with a sharp object, and then slowly moved up his body. Lewenstein felt nothing until his friend poked his upper chest. Back at his home in California, it became clear that the injury had permanently deprived Lewenstein of all control over his legs. He had limited use of his arms but could not pick anything up with his hands. His fingers were rigidly curled. Now 80, Lewenstein has outlived many predictions of his death, but that is not the most remarkable thing about him: He has spent no time, he says, feeling sorry for himself or regretting the accident. He knows he was riding the bike faster than he should have. And each day, he discovers new ways to be resourceful with what he does have -- and new reasons to feel grateful. "Some people feel sorry for themselves or mad at the world," he said. "I did not . . . after I was injured, I was so totally incapacitated and so much out of everything that every day turned out to be a positive day. Each day, I recovered a little more of my memory, of my ability to comprehend things." Lewenstein's story is especially instructive in light of a study published this week about a paradox involving happiness. Americans report being generally happier than people from, say, Japan or Korea, but it turns out that, partly as a result, they are less likely to feel good when positive things happen and more likely to feel bad when negative things befall them. Put another way, a hidden price of being happier on average is that you put your short-term contentment at risk, because being happy raises your expectations about being happy. When good things happen, they don't count for much because they are what you expect. When bad things happen, you temporarily feel terrible, because you've gotten used to being happy. "I have some friends who are very well off and have great lives," said Sonja Lyubomirsky, a psychologist at the University of California at Riverside. "If you ask them, they will say, 'I am very happy,' but the most minor negative events will make them unhappy. If they are traveling first class, they get upset if they have to wait in line. They live in a mansion, but |

| Article |

If It Feels Good to Be Good, It Might Be Only NaturalThe e-mail came from the next room. "You gotta see this!" Jorge Moll had written. Moll and Jordan Grafman, neuroscientists at the National Institutes of Health, had been scanning the brains of volunteers as they were asked to think about a scenario involving either donating a sum of money to charity or keeping it for themselves. As Grafman read the e-mail, Moll came bursting in. The scientists stared at each other. Grafman was thinking, "Whoa—wait a minute!" The results were showing that when the volunteers placed the interests of others before their own, the generosity activated a primitive part of the brain that usually lights up in response to food or sex. Altruism, the experiment suggested, was not a superior moral faculty that suppresses basic selfish urges but rather was basic to the brain, hard-wired and pleasurable. Their 2006 finding that unselfishness can feel good lends scientific support to the admonitions of spiritual leaders such as Saint Francis of Assisi, who said, "For it is in giving that we receive." But it is also a dramatic example of the way neuroscience has begun to elbow |

| Article |

When Seeing Is DisbelievingFour years ago tomorrow, President Bush landed on the USS Abraham Lincoln and dramatically strode onto the deck in a flight suit, a crash helmet tucked under one arm. Even without the giant banner that hung from the ship's tower, the president's message about the progress of the war in Iraq was unmistakable: mission accomplished. Bush is not the first president to have convinced himself that something he wanted to believe was, in fact, true. As Columbia University political scientist Robert Jervis once noted, Ronald Reagan convinced himself that he was not trading arms for hostages in Iran, Bill Clinton convinced himself that the donors he had invited to stay overnight at the White House were really his friends, and Richard M. Nixon sincerely believed that his version of Watergate events was accurate. Harry S. Truman apparently convinced himself that the use of the atomic bomb against Japan in the fading days of World War II could spare women and children: "I have told Sec. of War to use [the atomic bomb] so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors |

| Column |

Two Views of the Same News Find Opposite Biases You could be forgiven for thinking the television images in the experiment were from 2006. They were really from 1982: Israeli forces were clashing with Arab militants in Lebanon. The world was watching, charges were flying, and the air was thick with grievance, hurt and outrage. There was only one thing on which pro-Israeli and pro-Arab audiences agreed. Both were certain that media coverage in the United States was hopelessly biased in favor of the other side. The endlessly recursive conflict in the Middle East provides any number of instructive morals about human nature, but it also offers a psychological window into the world of partisan behavior. Israel's 1982 war in Lebanon sparked some of the earliest experiments into why people reach dramatically different conclusions about the same events. The results say a lot about partisan behavior in general -- why Republicans and Democrats love to hate each other, for example, or why Coke and Pepsi fans clash. Sadly, the results also say a lot about the newest conflicts between Israel and its enemies in Lebanon and the Palestinian territories, and why news organizations are being besieged with angry complaints from both sides. Partisans, it turns out, don't just arrive at different conclusions; they see entirely different worlds . In one especially telling experiment, researchers showed 144 observers six television news segments about Israel's 1982 war with Lebanon. Pro-Arab viewers heard 42 references that painted Israel in a positive light and 26 references that painted Israel unfavorably. Pro-Israeli viewers, who watched the very same clips, spotted 16 references that painted Israel positively and 57 references that painted Israel negatively. Both groups were certain they were right and that the other side didn't know what it was talking about. The tendency to see bias in the news -- now the raison d'etre of much of the blogosphere -- is such a reliable indicator of partisan thinking that researchers coined a term, "hostile media effect," to describe the sincere belief among partisans that news reports are painting them in the worst possible light. Were pro-Israeli and pro-Arab viewers who were especially knowledgeable about the conflict immune from such distortions? Amazingly, it turned out to be exactly the opposite, Stanford psychologist Lee D. Ross said. The best-informed partisans were the most likely to see bias against their side. |

| Article |

And the Evolutionary Beat Goes On . . .Stephen Jay Gould would have been pleased.  Stephen Jay Gould would have been pleased. No, not about his mug shot at the endpoint of evolution in the illustration above, but about the growing evidence that evolution is not just real but is actually happening to human beings right now. "From 1970 to 2000, there was a widespread view that although natural selection is very important, it is relatively rare," said Jonathan Pritchard, a geneticist at the University of Chicago. "That view was driven largely because we did not have data to identify the signals of natural selection. . . . In the last five years or so, there has been a tremendous growth in our understanding of how much selection there is." That insight has only deepened as scientists have gained the ability to read the entire human genome, the chain of "letters" that spell out humanity's genetic identity. "Signals of natural selection are incredibly widespread across the human genome," Pritchard said. "Everywhere we look, there appears to be very widespread signals of natural selection in many genes and many processes." Pritchard helped write a recent paper that identified some of those changes. The paper was published in the public access journal PLoS Biology. The research offers a fascinating snapshot into how the human genome has continued to change as humans adapted to new circumstances over the past 10,000 years. As people went from hunter-gatherers to agricultural societies, for instance, there is evidence of genetic adaptations to new diseases and diets. Europeans seem to be adapting to the increased availability of dairy products, with genetic changes that allow the enzyme lactase, which breaks down lactose in milk, to be available throughout life, not just in infancy. Similarly, East Asians show genetic changes that affect the metabolism of the sugar sucrose, while the Yoruba people in sub-Saharan Africa show genetic changes that alter how they metabolize the sugar mannose. Where starvation was once widespread in humans' evolutionary history, making it genetically advantageous to conserve calories as much as possible, the abundance of food in many countries today has led to the opposite problem -- risk factors and diseases related to metabolic overload, including obesity and diabetes -- suggesting these could be areas in which natural selection may currently be active, as genetic variations that help protect against such disorders gain selective advantage. |

| Article |

Forgive and Forget: Maybe Easier Said Than DoneWhen Lay was found guilty of conspiracy and fraud, Molinell cheered. Then, last Wednesday, before Lay could be sentenced to prison, he died. "I feel cheated that he didn’t have to do some sort of suffering," said Molinell, 63, of Longwood, Fla. "Even last year, he rented a yacht for his wife’s birthday to the tune of $200,000. For a birthday party!" "I can speak for a lot of ex-employees and retirees," she added. "It is almost like he got away with something again." Lay’s death has uncovered a world of hurt and anger among many victims of Houston-based Enron’s demise. And it brings to the fore an unusual challenge for those interested in the psychological nature of pain and forgiveness: What happens to victims when wrongdoers die before they are punished? |

| Article |

Science Confirms: You Really Can't Buy HappinessWhen Warren Buffett announced last week that he will be giving away more than $30 billion to improve health, nutrition and education, people all over America reflected on his remarkable generosity, pondered all the noble things the gift would achieve and asked themselves what they would do if someone were to give them that kind of dough. Halt that daydream: Turns out the Oracle of Omaha is a wizard at more than investing. When it comes to money, giving may buy a lot more happiness than getting. Buffett may have been thinking of his soul—"There is more than one way to get to heaven, but this is a great way," he said as he announced the largest gift in the history of the planet—but he may also have been keeping up with the latest psychological research. A wealth of data in recent decades has shown that once personal wealth exceeds about $12,000 a year, more money produces virtually no increase in life satisfaction. From 1958 to 1987, for example, income in Japan grew fivefold, but researchers could find no corresponding increase in happiness. In part, said Richard Layard of the London School of Economics, who has studied the phenomenon closely, people feel wealthy by comparing themselves with others. When incomes rise across a nation, people’s relative status does not change. |

| Article |

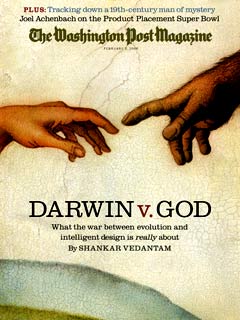

Post Magazine: Darwin v. GodReligious critics of evolution may be wrong about its flaws. But are they right that it threatens belief in a loving God?  Shankar Vedantam, whose article about Darwin’s theory and the competing theory of intelligent design appeared in Sunday’s Washington Post Magazine, was online Monday, Feb. 6, to field questions and comments. Shankar Vedantam writes about science and human behavior for The Washington Post.

|

| Article |

Eden and EvolutionReligious critics of evolution are wrong about its flaws. But are they right that it threatens belief in a loving God?  Ricky Nguyen and Mariama Lowe never really believed in evolution to begin with. But as they took their seats in Room CC-121 at Northern Virginia Community College on November 2, they fully expected to hear what students usually hear in any Biology 101 class: that Charles Darwin's theory of evolution was true. As professor Caroline Crocker took the lectern, Nguyen sat in the back of the class of 60 students, Lowe in the front. Crocker, who wore a light brown sweater and slacks, flashed a slide showing a cartoon of a cheerful monkey eating a banana. An arrow led from the monkey to a photograph of an exceptionally unattractive man sitting in his underwear on a couch. Above the arrow was a question mark. "There really is not a lot of evidence for evolution," says biology professor Caroline Crocker, who supports the theory of intelligent design. Crocker was about to establish a small beachhead for an insurgency that ultimately aims to topple Darwin's view that humans and apes are distant cousins. The lecture she was to deliver had caused her to lose a job at a previous university, she told me earlier, and she was taking a risk by delivering it again. As a nontenured professor, she had little institutional protection. But this highly trained biologist wanted students to know what she herself deeply believed: that the scientific establishment was perpetrating fraud, hunting down critics of evolution to ruin them and disguising an atheistic view of life in the garb of science. It took a while for Nguyen, Lowe and the other students to realize what they were hearing. Some took notes; others doodled distractedly. Crocker brought up a new slide. She told the students there were two kinds of evolution: microevolution and macroevolution. Microevolution is easily seen in any microbiology lab. Grow bacteria in a petri dish; destroy half with penicillin; and allow the remainder to repopulate the dish. The new generation of bacteria, descendants of survivors, will better withstand the drug the next time. That's because they are likely to have the chance mutations that allow some bacteria to defend themselves against penicillin. Over multiple cycles, increasingly resistant strains can become impervious to the drug, and the mutations |

| Article |

Culture and Mind: Psychiatry's Missing DiagnosisLast of three parts John Zeber recently examined one of the nation's largest databases of psychiatric cases to evaluate how doctors diagnose schizophrenia, a disorder that often portends years of powerful brain-altering drugs, social ostracism and forced hospitalizations. Although schizophrenia has been shown to affect all ethnic groups at the same rate, the scientist found that blacks in the United States were more than four times as likely to be diagnosed with the disorder as whites. Hispanics were more than three times as likely to be diagnosed as whites. Zeber, who studies quality, cost and access issues for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, found that differences in wealth, drug addiction and other variables could not explain the disparity in diagnoses: "The only factor that was truly important was race." |

| Article |

Culture and Mind: Psychiatry's Missing DiagnosisSecond of three articles RAIPUR RANI, India: Psychiatrist Naren Wig crossed an open sewer, skirted a pond and, in the dusty haze of afternoon, saw something miraculous. Krishna Devi, a woman he had treated years ago for schizophrenia, sat in a courtyard surrounded by religious pictures, exposed brick walls and drying laundry. Devi had stopped taking medication long ago, but her articulate speech and easy smile were eloquent testimony that she had recovered from the debilitating disease. Few schizophrenia patients in the United States are so lucky, even after years of treatment. But Devi had hidden assets: a doting family and an embracing village that never excluded her from social events, family obligations and work. Devi is a living reminder of a remarkable three-decade-long study by the World Health Organization -- one that many Western doctors initially refused to believe: People with schizophrenia, a deadly illness characterized by hallucinations, disorganized thinking and social withdrawal, typically do far better in poorer nations such as India, Nigeria and Colombia than in Denmark, England and the United States. |

| Article |

Culture and Mind: Psychiatry's Missing DiagnosisSidebar to Part 1 When a chronically depressed 9-year-old girl at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota became so sad that she stopped eating, Ethleen Iron Cloud-Two Dogs came up with a treatment plan: not antidepressant drugs, but a spiritual assessment, followed by a healing ceremony at a Lakota purification lodge that represents the womb. "There is a hole dug in the middle and rocks that are heated," she said. "Because we believe that everything has a spirit, rocks are addressed as grandfather spirits. The water is taken in and poured on the rocks -- the steam that results is the breath of the grandfathers which then purifies and renews us." Over the next three months, the girl recovered, said Iron Cloud-Two Dogs, who treats emotionally disturbed and suicidal children at a federally funded Native American mental health program called Nagi Kicopi, "Calling the Spirit Back." The healer dismissed those who demand evidence that her techniques work. |

| Article |

Culture and Mind: Psychiatry's Missing DiagnosisFirst of three parts When UCLA researchers reviewed the best available studies of psychiatric drugs for depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and attention deficit disorder, they found that the trials had involved 9,327 patients over the years. When the team looked to see how many patients were Native Americans, the answer was… Zero. "I don't know of a single trial in the last 10 to 15 years that has been published regarding the efficacy of a pharmacological agent in treating a serious mental disorder in American Indians," said Spero Manson, a psychiatrist who heads the American Indian and Alaska Native Programs at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Aurora. "It is stunning." |